The Dow Chemical Company made a pesticide that has been linked to slowed brain growth in developing fetuses, but misrepresented the chemical’s harm in studies submitted to regulators, according to a damning new report.

In a study published in the journal Environmental Health this month, scientists revealed the raw data behind studies that the company (now DowDuPont) submitted to European regulators in the late 1990s regarding the chemical, chlorpyrifos. The scientists obtained the data through public information requests to the Swedish Chemicals Agency. Studies with identical titles were also submitted to the EPA, according to agency records.

The researchers tried to repeat Dow’s analysis but found that the experiments were incorrectly designed. Their new report alleges that the company’s original analysis of the data — conducted by third-party lab Argus Research Laboratories in Pennsylvania — masked damage that the chemical had caused to baby rat brains.

“It’s really a rare case that researchers get their hands on this raw data and these reports,” Axel Mie, an assistant professor at the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden who co-authored the new report, told BuzzFeed News.

DowDuPont contests the report. In a brief statement, a company spokesperson told BuzzFeed News that it “strongly refutes accusations of data manipulation or deceit in any studies.” He said that the study cited by Mie and his colleagues conformed to all EPA guidelines and has been reviewed by regulators in the US, Canada, Australia, and the EU. Argus Research Laboratories, now a subsidiary of Sanofi, did not respond to a request for comment.

The company’s critics say this data is important because it was submitted ahead of chlorpyrifos’s approval in the European Union in 2006, and also in reports to the EPA in the late 1990s, before the agency set new limits on the chemical's use in 2000.

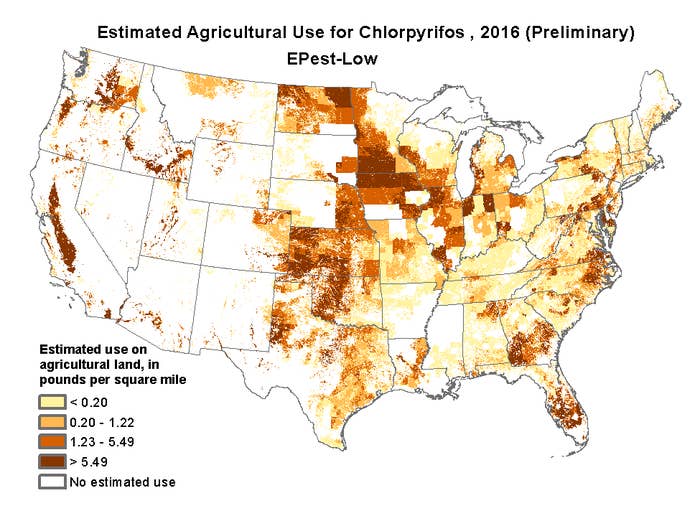

Chlorpyrifos has been used as a pesticide since at least 1965, but it has raised controversy in the past few years. In 2000, the EPA and companies that make chlorpyrifos agreed to stop most home uses of the chemical as an insecticide, and the EPA’s limits on its use have gotten increasingly restrictive.

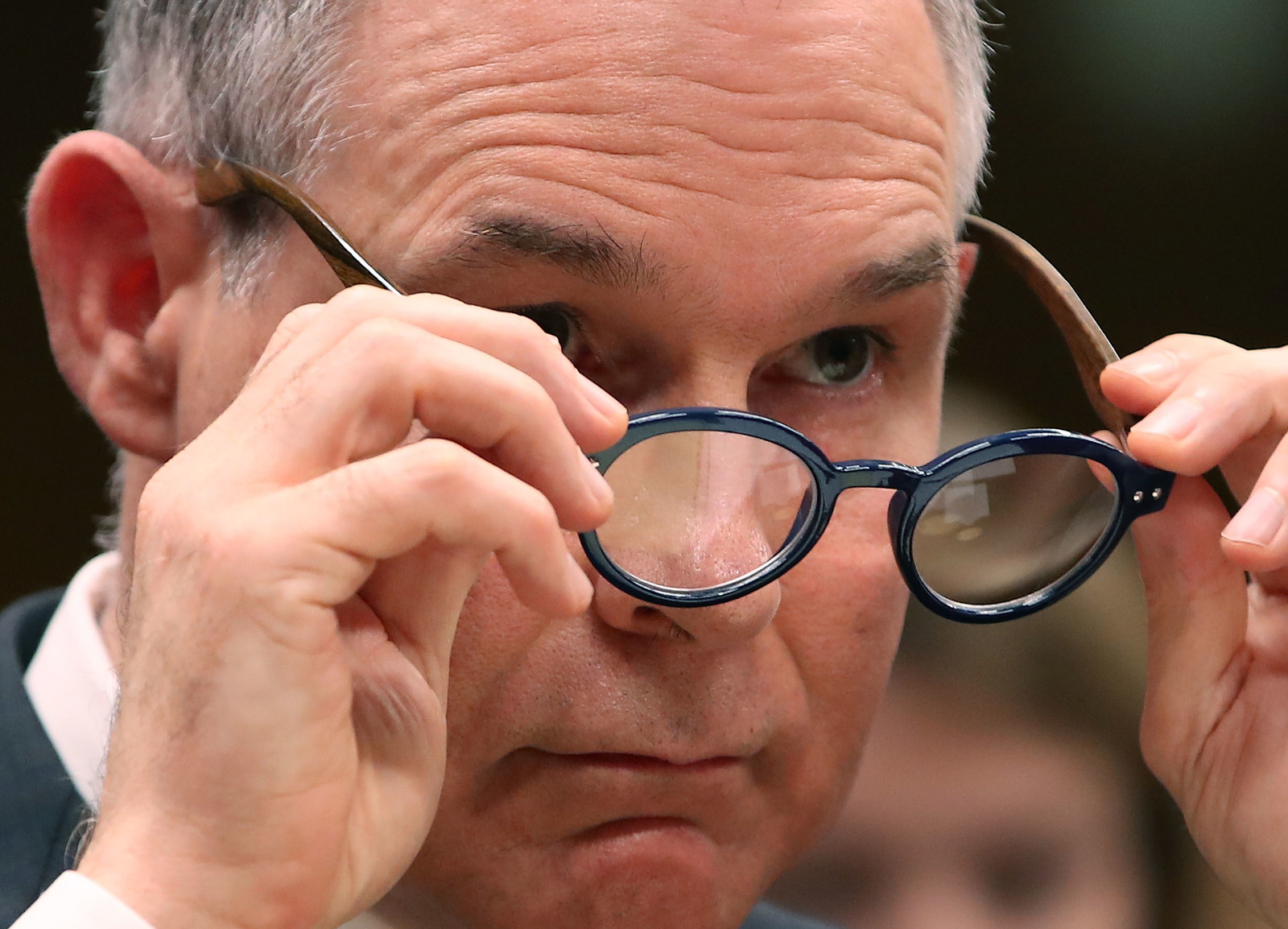

After independent analyses linked developmental issues and lower IQ to children born to mothers who were exposed to the pesticide, EPA scientists made a case for banning use of the chemical as a crop pesticide because it could reach people on produce. After Scott Pruitt took the helm at the agency in 2017, one of his signature decisions was to walk back that ban, attracting a lawsuit from environmental groups. A judge ruled in August of this year that the EPA must reconsider its decision and enforce a ban, but the agency has appealed that ruling.

If the rules related to this chemical were based on flawed data, critics say, it’s relevant to the debate.

“I think this is crucial information for decision-makers to know — that some of the studies that EPA was relying on have these serious problems and should be reconsidered,” Veena Singla, associate director of science and policy at the Program on Reproductive Health and the Environment at the University of California, San Francisco, told BuzzFeed News.

“It’s pretty mind-boggling,” Patti Goldman, a managing attorney at Earthjustice — one of the groups suing the EPA’s delay of the chlorpyrifos ban — told BuzzFeed News.

Goldman said that Dow has been challenging independent studies that linked the pesticide to a drop in IQ of children whose mothers had been exposed to the pesticide. In responses to the EPA over the years, and in a brief filed as part of the lawsuit, the company has argued that laboratory studies in rats are superior ways to test neurotoxicity of the chemical.

“I thought that’s where the debate was. I didn’t expect the revelation that their own lab studies may be misleading,” Goldman said.

Singla said she has seen similar issues raised in other industry studies whose data and reports are privately submitted to agencies that regulate them.

The new information just adds to the “mountains of evidence” that chlorpyrifos should be banned for all uses, she said. “It’s just one more nail in that coffin.”

In the new paper, Mie and his colleagues describe a series of shortcomings in Dow’s methods. For instance, the company did not correctly model human brain development in its rat models, the authors wrote. A growth spurt in brain development takes place when human babies are still fetuses, but the corresponding spurt occurs in rat pups after they are born. A test to measure neurotoxicity in developing rat brains did not dose newborn pups with the chemical after they were born, so it did could not correctly indicate the conditions a developing human brain would face, they said. “For chlorpyrifos, it is documented that it is not adequate.”

The researchers also found fault with the company’s assertion that the chemical was only toxic to the brain at high levels. They say the raw data measured rat pups’ cerebellums shrinking at low, medium, and high doses of the pesticide, but the analysis did not show that finding.

In a memo reviewing this study in 2000, the EPA flagged this aspect of the analysis and described it as “inappropriate and inconclusive manipulation of the data.”

In a third criticism leveled at the company, the researchers point out that a positive control, designed to detect whether the experimental setup was working, failed. That setup was unable to detect an expected adverse outcome in rat pups that were fed lead nitrate — even though lead is a known developmental neurotoxin.

“They weren’t able to detect developmental neurotoxicity with a metal that’s known to cause it,” Singla said. “That calls into question all of the results.”

Mie and his colleagues stated that they did not find evidence of deliberate misrepresentation — they were simply pointing out mistakes in the reports.

DowDuPont told BuzzFeed News that its studies had been peer-reviewed and published, underscoring their validity. Mie countered that “the published material did not allow readers to detect these problems that only became obvious when examining the detailed study records.”

“I am disappointed that the pesticide producer stands by these erroneously conducted and erroneously reported test results,” Philippe Grandjean of Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and one of Mie’s co-authors on the new paper, wrote in an email to BuzzFeed News.

Goldman said the EPA is obliged to include such new information in its regulation of the pesticide, although there is no set timeline for that action.