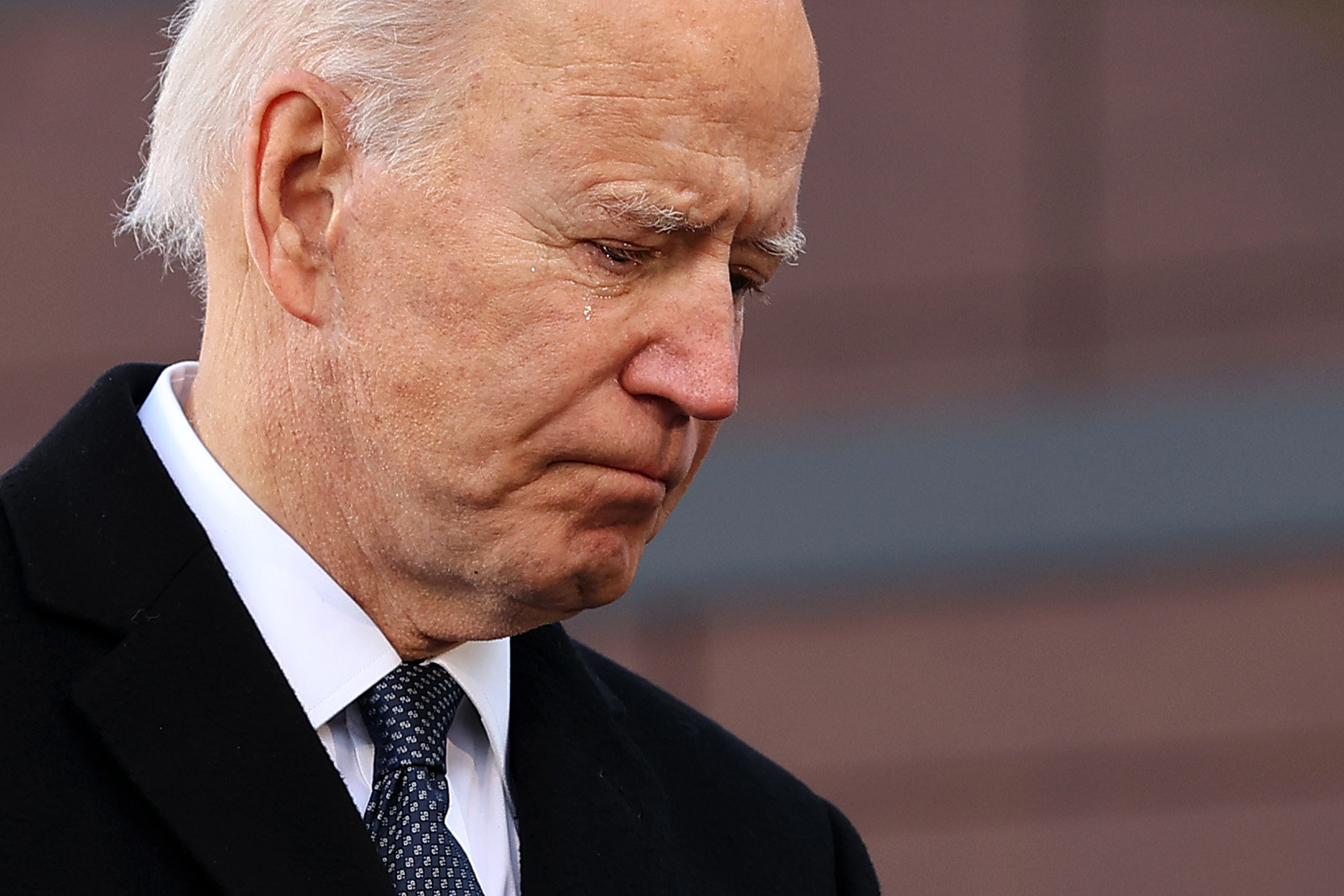

On the eve of his inauguration, and just hours after the US reached the grim milestone of more than 400,000 COVID-19 deaths, President-elect Joe Biden gathered at the head of the Lincoln Memorial reflecting pool on Tuesday.

As the sun set over DC and gospel singer Yolanda Adams performed Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” 400 lanterns were lit in a moment broadcast on televisions nationwide to remember those Americans who have died as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. At the nearby Washington National Cathedral, and in churches across the country, bells rang out in memory of the dead.

“To heal, we must remember. And it is hard sometimes to remember, but that’s how we heal. It is important to do that as a nation. That is why we are here today,” said Biden. “Between sundown and dusk, let us shine the lights in the darkness along this sacred pool of reflection and remember all who we have lost.”

Tuesday’s ceremony was the first time since the pandemic began that the executive branch of the US government — albeit, the incoming executive branch — had stopped for a national moment of grief. It signaled not only the arrival of a new administration, but a new chance for the nation to reckon collectively with the toll the virus has taken in every corner of the country.

“For many months, we have grieved by ourselves,” said Vice President–elect Kamala Harris in remarks. “Tonight, we grieve — and begin healing — together.”

But that healing is complicated for the hundreds of thousands of Americans who have had loved ones die. While Tuesday night’s memorial was the first step toward national recognition of how much has been lost, and Biden’s empathy can be a comfort, for some of the people struggling there are deep questions of how they’re supposed to recover and what responsibility the federal government should have.

Chioma Oruh, 40, whose father died of COVID-19 in May after getting infected in a nursing home, said she appreciated the idea of the memorial, but it doesn’t do much for the unresolved anger and pain she has over her father’s death.

“You want to be able to feel OK and be in community with each other and celebrate and mourn and collaborate,” Oruh said. “At the same time, that happens once a government creates mechanisms through which accountability can happen. I don’t think we’ve gotten to that point where that accountability happens.”

Biden will start his term in office on Wednesday with multiple national crises to contend with. For months, he has been clear that addressing the pandemic is one of his day-one priorities, and the decision to hold a memorial service, even brief, to acknowledge those who have died emphasizes the task he has ahead of him in trying to change the trajectory of COVID-19 in the US. His own chief of staff estimates 100,000 more Americans will die next month from the virus.

Biden convened a COVID-19 taskforce soon after winning the election to start talking with governors, medical experts, and others. Last week, he announced a $1.9 trillion pandemic relief plan. His proposal is focused on resources for testing, vaccines, and economic recovery moving forward. But his plan doesn’t include the measures Oruh wants to specifically help families who had a loved one die as a result of negligence or to investigate any of the deaths that have already happened.

A ceremony like Wednesday’s can’t really begin to help her heal, Oruh said, unless there’s restitution to those who have had loved ones died because of how poorly the pandemic has been handled by authorities and private businesses like some nursing homes. “I can't sue the nursing home for exposing my dad for COVID,” she said.

“In other spaces, you would have a truth and reconciliation commission, some kind of hearing. People talk about reparations,” Oruh said. “Those things are not outside of the democratic process, they are what makes democracy the best system ... COVID is no exception to that rule.”

But the significance of the incoming president acknowledging the grief that’s gripped so many Americans through the pandemic is not lost on Micki McElya, a history professor at the University of Connecticut and author of The Politics of Mourning: Death and Honor in Arlington National Cemetery.

“So many people — really since from earlier days of the pandemic — have looked to this tradition of the mourner-in-chief, the emotional register and leadership established by the president, or could be or should be established by the president,” said McElya. But Americans, she said, have not found that in Donald Trump.

Grief has been a throughline of Biden’s life and career. He was sworn into office as a senator for the first time in January 1973, just weeks after his wife Neilia and daughter Naomi died in a car accident. He was 30 years old. His son Beau, who survived that crash as a child, had a rising career in Democratic politics. He died in 2015 at 46 from brain cancer.

“I think with Biden, those deep associations with his own personal tragedy and losses and the fact they have always been profoundly public, they have been enacted publicly. I do think that gives him an air of authenticity and sincerity in a role that people in the past have very much looked to and been looking for during the pandemic,” said McElya.

Speaking about Beau earlier on Tuesday during his farewell to his home state of Delaware, where he has been based since the pandemic began, Biden was clearly emotional. “I only have one regret: that he’s not here. Because we should be introducing him as president,” he said.

For decades, Biden has forged loyalty with people — from voters at campaign events to political friends and influential allies — through his ability to empathize and comfort, particularly in times of grief. As he traveled the country on the pre-pandemic campaign trail, he frequently met people who'd had someone close to them die and consoled them. Others would come to his events after having met him decades ago during a period of grief in their lives and recall his kindness.

His acknowledgment of losses Americans have endured over the past year is a significant break from his predecessor’s approach to the pandemic. Fearing political repercussions at every step, Trump minimized the gravity of the crisis and denied the US death toll even as it surpassed that of every other country in the world.

Trump, in his prerecorded farewell speech released Tuesday, did not specifically address the scale of the destruction COVID-19 brought to the US under his administration. Instead, he touted his administration’s response on vaccines.

He did, though, come close to acknowledging the toll at one point in his speech. “We grieve for every life lost,” he said, “and we pledge in their memory to wipe out this horrible pandemic once and for all.”

But the outgoing leader never gave any sense of the scope of that loss — of just how many Americans have died in the final year of his presidency.

If the US is to truly begin to heal from the ills of the pandemic, McElya said, there must be many more moments like Biden’s ceremony on Tuesday night. And beyond that more accountability.

"If something approaching unity is to be achieved, it requires a clear-eyed sober confronting of the damage done and all we've lost," said McElya. "What this event also symbolizes and what it can achieve is not only to honor them but to reckon with why they're gone."

CORRECTION

Oruh's father died of COVID-19 in a hospital. A previous version of this post misstated where he died.