Your devices are tracking you all the time. You just don’t know it yet.

When you consent to sharing your data with many popular apps, you’re also allowing app developers to collect your data and sell it to third parties through trackers that supply advertisers with detailed information about where you live, work, and shop.

In November 2017, Yale Privacy Lab detected trackers in over 75% of the 300 Android apps it analyzed. A March 2018 study of 160,000 free Android apps found that more than 55% of trackers tried to extract user location, while 30% accessed the device’s contact list. And a 2015 analysis of 110 popular free mobile apps revealed that 47% of iOS apps shared geo-coordinates and other location data with third parties, and personally identifiable information, like names of users (provided by 18% of iOS apps), was also provided.

While the presence of trackers doesn't necessarily mean developers are breaking the rules, emails obtained by BuzzFeed News show how data marketing firms convince developers to include trackers in their apps: cash.

“Most third-party services operate in the background and do not provide any visual cues inside the apps, effectively tracking users without their knowledge or consent while remaining virtually invisible,” wrote researchers in a February 2018 study. Meanwhile, the collected data is virtually untraceable as it is passed from data broker to marketers to others.

Apple and Google’s policies prohibit sharing or selling user data with third parties unrelated to improving the app experience or displaying ads in the app.

In emailed statements to BuzzFeed News, an Apple spokesperson wrote that “immediate action” is taken on policy violators, while a Google representative said, “We have policies that disallow apps in Google Play that are deceptive or misuse personal data, and we remove apps that violate our policies.”

But it’s easy for developers to evade detection. Trackers are tucked away in the app’s codebase, and developers can share user data outside of their apps by uploading it to a server.

@charlesproxy also: turns out some stargazing app I installed many years ago has been sending my location to their servers every couple of minutes for the last 4 years 🤯 https://t.co/1n31O1YkKa

Here’s how location tracking works: Marketing companies offer app developers cash in exchange for implementing a few lines of code — called an SDK or “software development kit” — into their apps. The SDK sucks up all the user data that the app has access to, and the developer gets a check every month in return. Marketers use the location data to target advertising campaigns based on where you are (a coupon for donuts when you’re next to a donut shop, for example) and to measure whether an online ad drove you to visit a retail location. The goal is to understand your habits and ultimately, get you to buy something.

Because data collection for the purposes of advertising is either disclosed in long-winded privacy policies or not at all, it’s difficult to tell which apps have trackers and which don’t.

Nearly all types of apps include trackers. Major companies whose businesses are built on advertising-based revenue — like Facebook and Facebook-owned Instagram, as well as Google’s suite of apps including Gmail and YouTube — collect a wealth of detailed user information. But because Facebook and Google run their own advertising ecosystems, not sharing their user data protects their competitive advantage. But smaller companies do have financial incentive to share data with third parties.

A March 2017 email obtained by BuzzFeed News from Teemo, a Paris-based marketing company, reveals how developers are approached with pay-for-data schemes. In it, a Teemo employee laid out a “pure data play”: Developers place Teemo’s SDK into their app and Teemo pays $4 per thousand users per month. ”You have 1 million [monthly active users] > 4000 USD,” the email says. “Straight to your pockets.”

In February 2018, researcher Will Strafach of Sudo Security discovered that three popular US-based iOS apps were sending people’s location information to Teemo. Perfect365, Kim Kardashian’s selfie-perfecting app of choice; the Weather Live - Local Forecast app (ranked #4 in the weather apps category); and The Coupons App sent latitude and longitude, as well as timestamps for departure and arrival to GPS coordinates, to a Teemo server. Strafach confirmed to BuzzFeed News that the latest versions of the apps had Teemo code embedded.

After a BuzzFeed News inquiry to Apple, Perfect365 and The Coupons App are no longer available in the App Store. Teemo did not respond to BuzzFeed News’ request for comment.

A Perfect365 spokesperson said, “The only location data we collect is from users that have opted in” to location sharing. In an email, The Coupons App’s CEO, Aaron Rzadczynski, said the app’s users consent “to absolutely anonymous, passively-collected location data both prior to install and post-install.” Weather Live did not respond to requests for comment.

Though these three apps each inform users that they are using location data, none say they’re sharing it with a third party.

Even restricting location access on an app won’t necessarily prevent it from revealing your location. Abbas Razaghpanah, a researcher at Stony Brook University, found 581 Android apps, including dozens geared toward preschool-age children made by a developer called BabyBus, shared Wi-Fi access point names and MAC addresses (a unique identifier assigned to all network devices, like your router), which can be cross-referenced with a public database to pinpoint your location. BabyBus did not respond to BuzzFeed News’ request for comment.

In 2016, the Federal Trade Commission settled with mobile advertising company InMobi for employing the same tactics on hundreds of millions of consumers, including young children.

Location data can also be used to infer sensitive, personal details about you. Copley Advertising used phone location data to target young women near reproductive health clinics across the country, like Planned Parenthood, with ads from anti-abortion groups. In April, the advertiser reached a settlement with the Massachusetts Attorney General that bars it from targeting women with these ads.

It’s hard to see where marketers take your data, because their policies often allow them to resell it: In one study, researchers found that eight out of the top 10 ad-tracking companies reserve the right to sell or share data with other organizations.

“It’s very difficult to get any idea of where it goes, and who it goes to. The ecosystem is extremely opaque, which is part of the problem,” said Cooper Quintin, a security researcher at the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Marketers say that the information they collect is anonymized, but it’s easy to de-anonymize location data, according to several studies. “The anonymization debate is something that needs to be challenged. It’s misleading,” said Michael Kwet of the Yale Privacy Lab.

Data management companies like Salesforce create profiles of people through what is referred to as “stitching together” data sets, says Kwet. “Our behavior is very individual. It’s not possible to have a rich set of data and have that be truly anonymous,” Kwet explained. In an emailed statement, a Salesforce spokesperson denied that they are a data management company, but rather "the leader in CRM (Customer Relationship Management)," and wrote, "Salesforce does not create profiles of people. Companies turn to Salesforce technology to help build and grow customer relationships, leveraging their own information to do so."

It's hard for Apple and Google to police developers' behavior on their massive platforms: Both the iOS App Store and Google Play Store host over 2 million apps each. Moreover, both say protecting user privacy is also the developer’s responsibility.

“Developers must also take the appropriate steps to protect such data from unauthorized use, disclosure or access by third parties,” an Apple spokesperson said in a statement. Google said it automatically scans Android apps for malicious code but also relies on users and developers to flag apps for review.

But it’s impossible for either Google or Apple to prevent data marketing firms from coaxing developers with monetization proposals.

“It’s flat-out selling user data for cash. There’s no other reason to do it,” said David Barnard, the founder of app company Contrast.

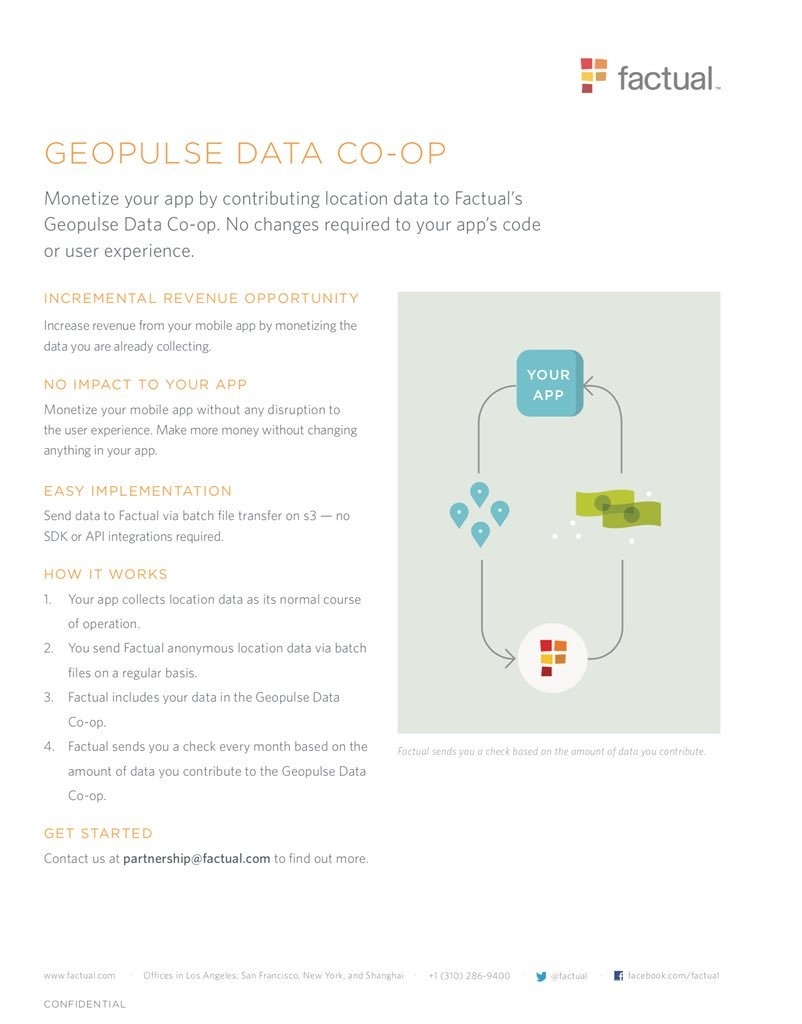

In a document that a representative from Factual, a location data company, shared with Barnard in February 2017, the company laid out just how easy it is to sell user data collected from Barnard’s app Weather Atlas. According to the sheet, Factual didn’t require the implementation of an SDK — instead, the developer was instructed to upload user location data to an Amazon server run by Factual. Based on the amount of data uploaded, the developer would receive a sum of money via check every month. In a follow-up email, Factual said it was interested in collecting the user’s advertising identifier, latitude/longitude, and timestamps.

The proposition was tempting: “This is what puts food on the table for my family. … There’s a direct monetary incentive to break the rules,” Barnard said.

The Texas-based app maker told BuzzFeed News he turned Factual down. “Once I sold this data, even if I disclosed, I had zero control over how it was used, and no idea if people I sold it to would give it to someone else.”

Factual maintains that it works to protect consumer privacy. “There are certain behaviors we do not share with partners, and work actively with a number of industry bodies to adhere to best practices, like the Network Advertising Initiative (NAI),” said Brian Czarny, who leads the company’s marketing efforts. NAI is a nonprofit dedicated to “responsible data collection and its use for digital advertising,” according to its website.

In advance of May 25, when the EU’s upcoming data protection regulation, GDPR, kicks in, Factual is removing data that was obtained without explicit consent from European citizens and rebuilding its European database.

For US citizens, similar legislation may be coming. After public outcry over news that up to 87 million Facebook users may have had their data inappropriately accessed by the political analytics firm Cambridge Analytica, CEO Mark Zuckerberg said he would be open to regulation.

“Now that Cambridge Analytica has our attention, we should be thinking about all the myriad ways our data is scraped and sold. We shouldn’t treat Cambridge Analytica as the only people doing bad in this space,” said the EFF’s Quintin.

But change will require pressure from the industry at large. “It’s not an individual problem, it’s an ecosystem problem. There’s a push to normalize physical location tracking, and it’s being used to manipulate and herd people. If you want to opt out, it’s not easy,” said Yale’s Kwet.

“There’s a push to normalize physical location tracking, and it’s being used to manipulate and herd people. If you want to opt out, it’s not easy."

“It’s a very fragmented process — you have to read the privacy policy for each app, then send us an email, then go to this website. If you make it a little extra work for people, then they won’t do it,” Kwet explained.

Barnard hopes that developers will indeed put the onus on themselves to prevent their users from being constantly monitored: “As the trust of iPhone owners erodes through scandals like Facebook, Uber, AccuWeather … I’d like to think that indie devs like myself are a bastion of hope and trust for users. Indie devs can have that marketing angle. We should be the trusted little guys, respecting our users’ privacy when the big companies and scam apps won’t.”

What You Can Do

- If you have an iPhone, go to the Settings app > Privacy > Advertising and enable Limit Ad Tracking. There, you can also reset your advertising identifier, which clears the data associated with your advertising number. You can also opt out of location-based ads by going to Settings > Privacy > Location Services > scrolling all the way down to System Services and disabling Location-based Apple Ads.

- If you have an Android device, go to Settings > Google > Ads > and enable Opt out of ads personalization. You can also reset your advertising ID there. All Google users can turn off ads personalization through the Ad Settings page.

- Yale’s Michael Kwet also suggests Android users try the F-Droid App Store, because it offers apps without tracking and has a strict auditing process. Android users can also try UC Berkeley’s Lumen Privacy Monitor, which provides detailed reports of what data apps on your phone are sending off to third-party servers.

- Firefox has a free mobile browser built just for blocking ads and ad trackers, called Firefox Focus. For browsing on the web, you can use the Privacy Badger browser extension with Chrome or Firefox, which is an ad and ad tracker blocker by the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

- When you download an app and it asks for any kind of permission, consider whether it really needs it. For example, a weather app may work just fine with your zip code, and you won’t need to grant it access to your phone’s GPS.

- If an app is free, comb through its website and try to understand its business model. Open its privacy policy and look for a section called something like “Information we collect about you.” If it’s not clear, try contacting the developer yourself to ask for more information.

UPDATE

This post has been updated with a statement from Salesforce.