SAN FRANCISCO — In March, Twitter cofounder Biz Stone tweeted a screenshot of an iPhone homescreen along with a message: “Notice our new prototype? … It’s called ‘twttr.’ The bird flew away from the app icon representing: Simplicity. Blue sky thinking. We’re re-working. Not there yet: hence, no logo.”

Twitter, predictably, immediately dysregulated in response. “Most moronic design decision ever made.” “It’s horrible.” “Awful.” The most viral reply leaned on a popular Twitter trope to poke fun at the platform’s inability to ban bad actors: “everyone: get rid of the Nazis. yall: we got rid of the logo.”

And yet, it was all a misunderstanding. Twitter hadn’t changed its icon at all. It launched a separate app, “twttr,” as an external, public prototype to experiment with new features it’s considering rolling out on Twitter itself; a way to test things in public. Stone clarified: “Folks, the bird isn’t going away from Twitter.”

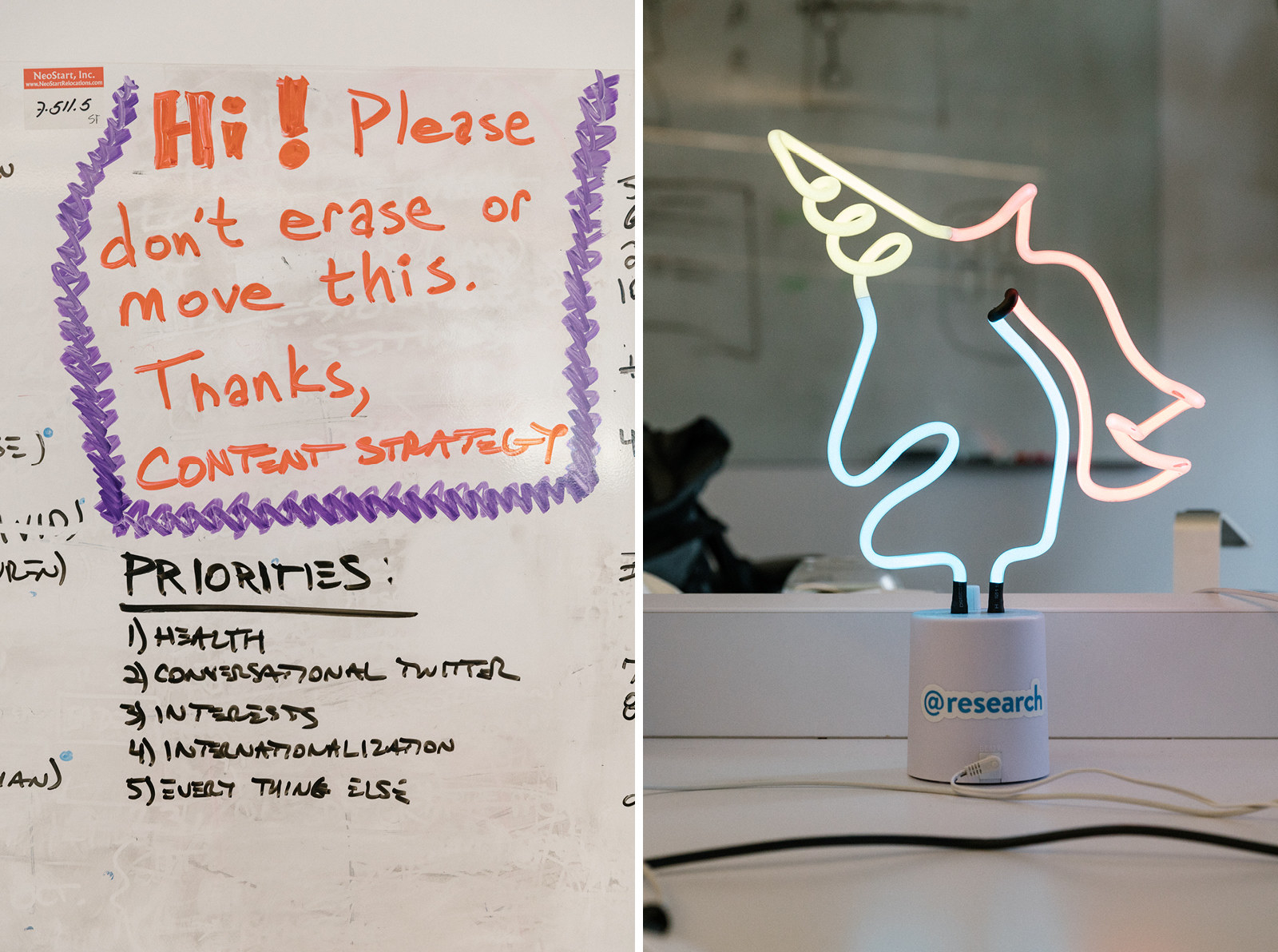

The entire episode was a microcosm of Twitter’s larger problems, some of which this new prototype itself is meant to address: everyone yelling, and no one talking. “Little t” twttr is a part of the company’s grand plan to treat the platform’s underlying issues, rather than just its symptoms. The idea is that what it learns from small-t twttr will help big Twitter foster conversations, rather than outrage.

Thanks to its open, freewheeling public platform, and stance on free speech, Twitter has been a hothouse for ginning up disinformation, harassment, and outrage. A lot of these problems were caused, the company’s leadership believes, by product decisions made early in its existence. And in very Silicon Valley fashion, the San Francisco–based company is now trying to solve these institutional problems with product fixes, without killing its platform's open, real-time magic. But it isn’t exactly sure what those fixes are, and it knows that massive changes to its product, rolled out widely, might even make things worse. So, yes, the company is fundamentally overhauling its product, but it’s starting with baby steps on twttr.

Over several days this spring, BuzzFeed News met with Twitter’s leadership and watched as twttr’s team worked on its first big push: helping people better understand what’s being said in often chaotic conversations. The team thinks that if people took more time to read entire conversations, that would help improve their comprehension of them. Maybe they wouldn’t jump to react. Maybe they’d consider their tone. Maybe they’d quit yelling all the time.

Or maybe, not even thousands of deeply studied, highly tested product tweaks will be enough to fix the deep-seated issues with a culture more than 13 years in the making.

A couple of weeks after Stone’s tweet, and after about 4,700 people had been using the new twttr prototype, Twitter senior user researcher Cody Elam was at work, late, looking at a massive spreadsheet. He had spent the past week collecting and reviewing every single piece of feedback — 600 tweets and 1,986 survey responses — from the program’s initial participants and, now, was tasked with identifying the most salient, important themes among their comments.

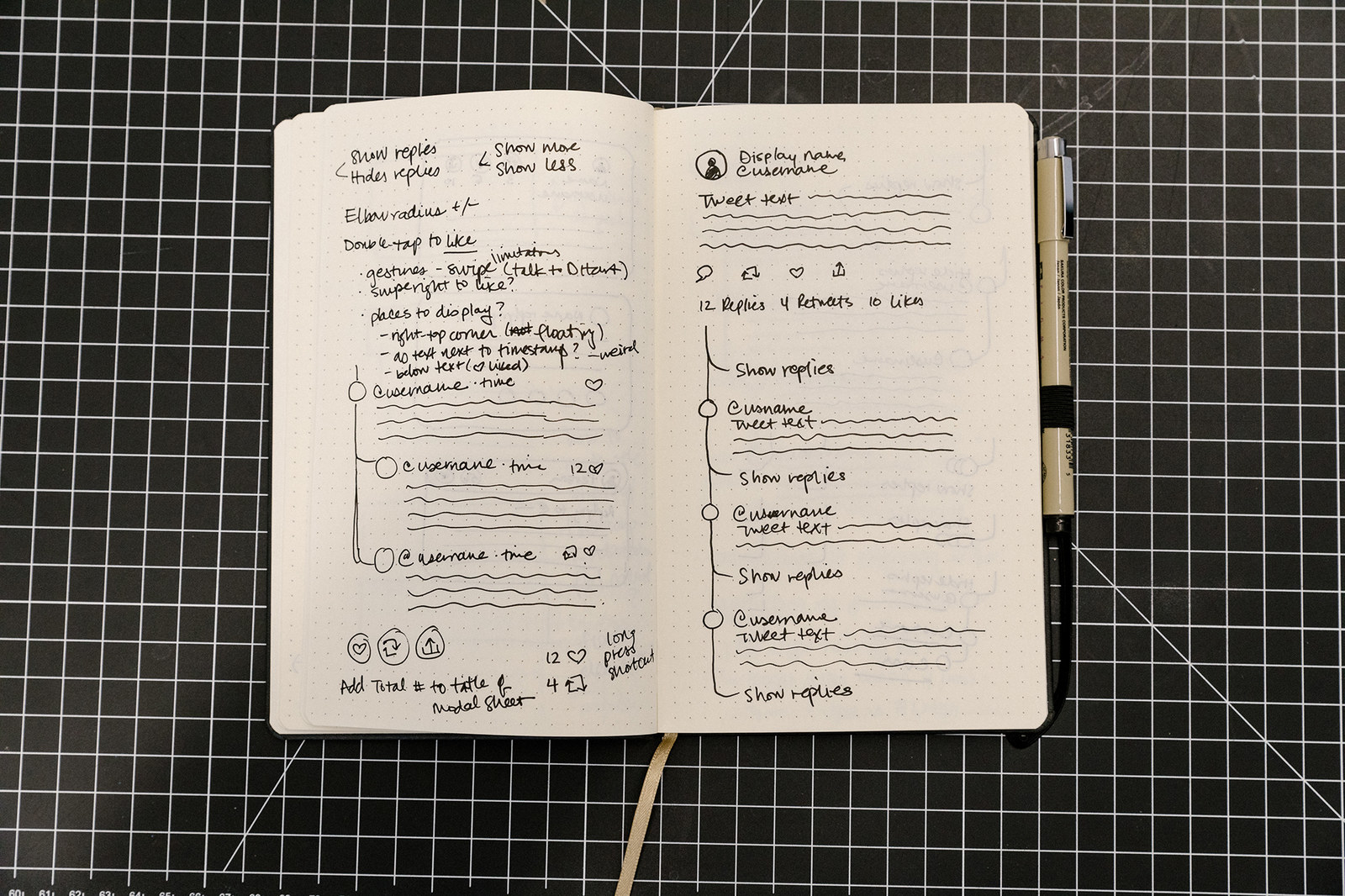

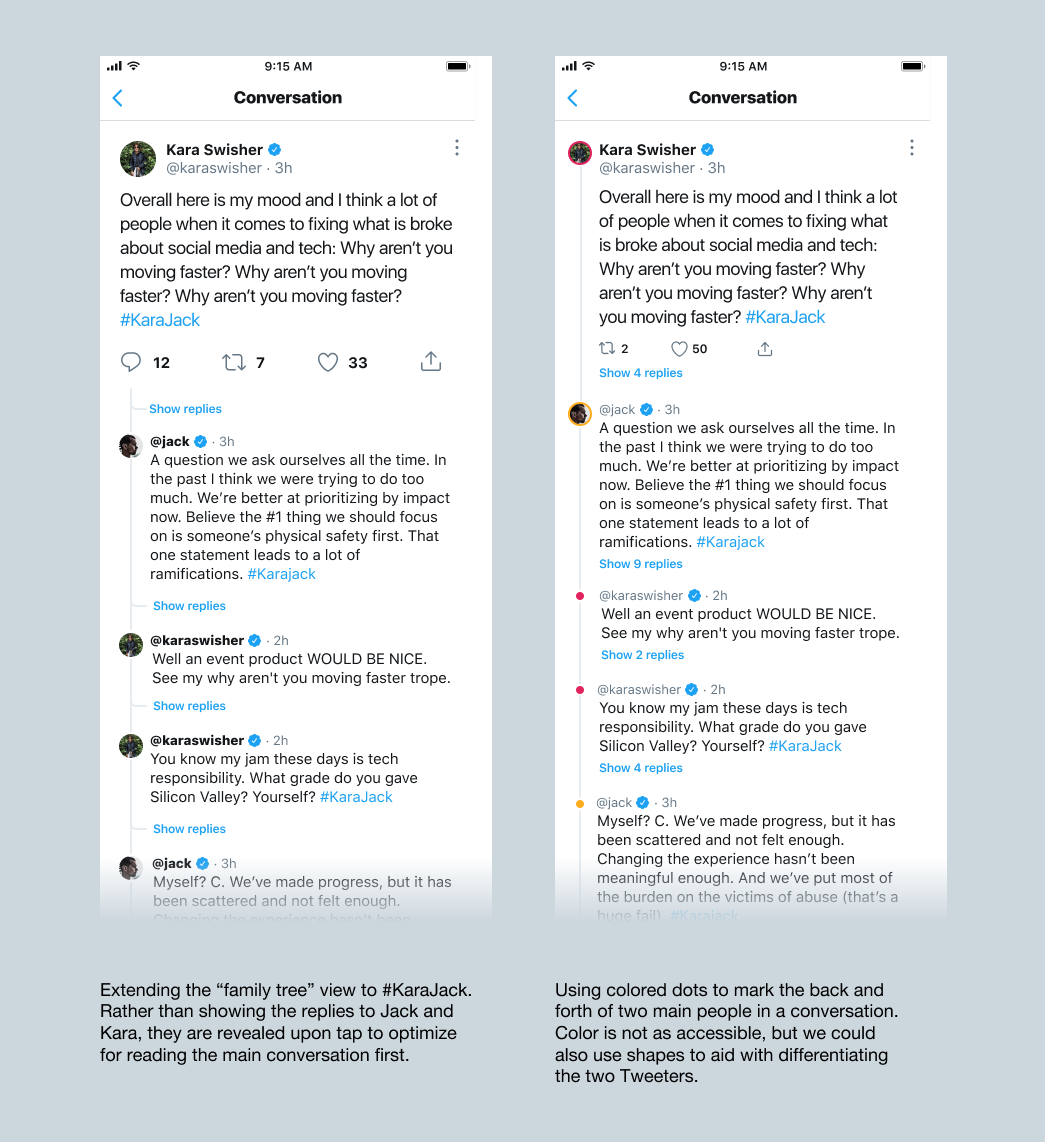

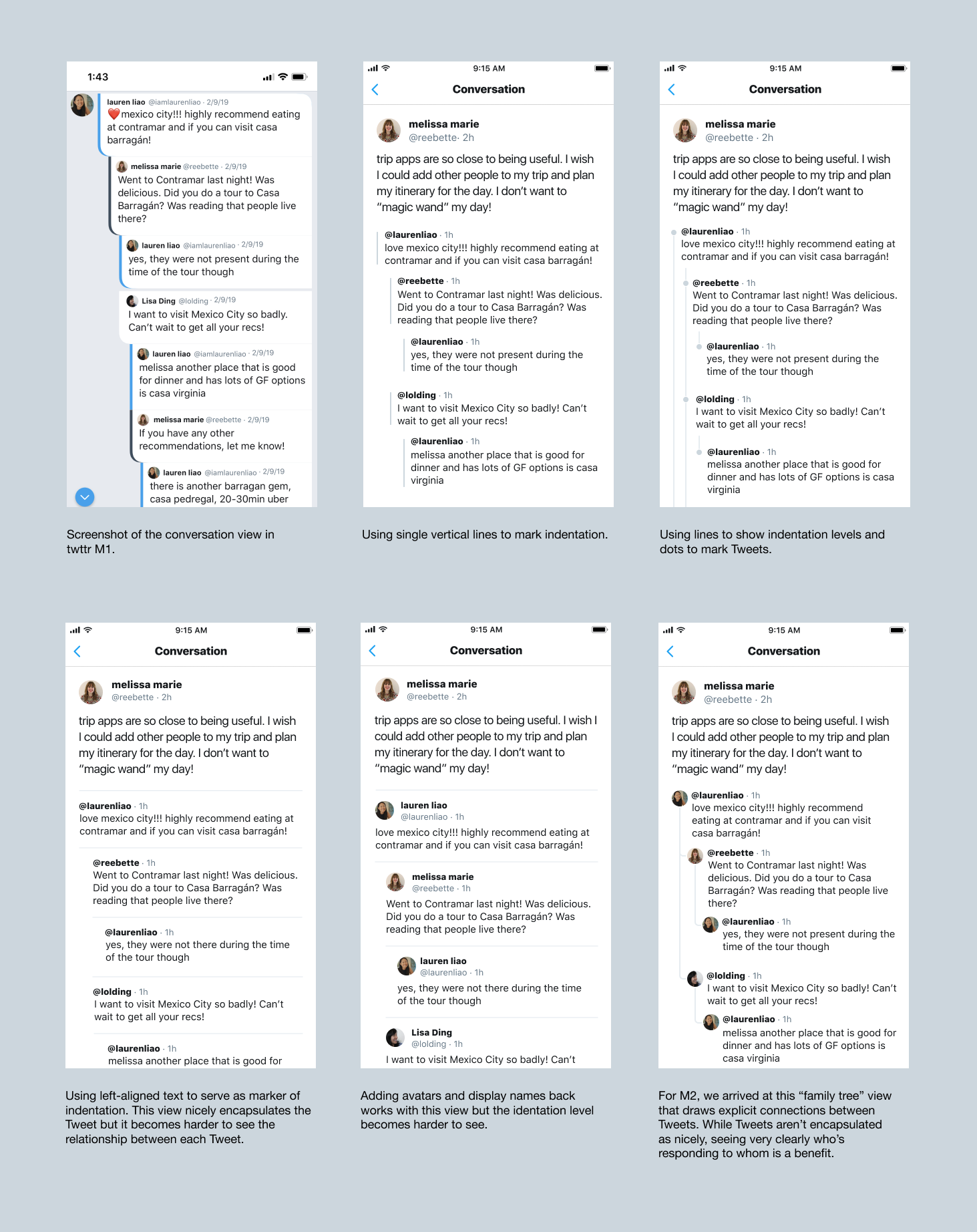

The twttr team began by testing what happens if the app more clearly shows who’s replying to whom. They also hid likes and retweet counts — Twitter’s primary incentives — behind a tap to put the primary focus on reply text. Now they were about to see, for the first time, what people thought.

Some of that initial feedback said that the bubbly design made Twitter feel more like a chat, and that it was easier to understand who was responding to what. Others were confused by the different colors labeling replies (blue for people you follow, and black for the original tweet’s author). People generally seemed to like the new design, Elam deduced, except for one change that received a more mixed response: hiding the metrics.

This wasn’t entirely unexpected. It was a step that they had suspected would not be popular, at least at first, but was maybe a necessary sacrifice to nudge its users in the right direction. Some of twttr’s first testers were feeling unnerved about the like and retweet buttons, and their counts, which had been seemingly removed from replies. In a meeting at Twitter’s San Francisco headquarters with the 13-person team behind twttr, Elam presented the users’ concerns.

“There’s a critical group of people — 20% or so — who are saying, ‘I prefer the way that likes are displayed in the main app,’” he told the group. “For some people, they feel like it’s more work when they don’t have something to anchor to. Like, if I’m looking at different replies, where should I draw my eye to, in terms of the popularity of tweets?”

Want to support more reporting like this? Become a BuzzFeed News member today.

While some users said the new design made replies “more equal,” others complained they couldn’t gauge the importance of replies without doing more work (that extra tap).

“Twitter already ranks replies based on some of that like and retweet data, and so if that information is removed, it may be confusing why you’re seeing one reply versus another,” posited Sara Haider, who is leading the twttr efforts.

A week later, at another feedback review session, Elam told the group that a significant enough number of testers in Japan, Twitter’s other major market outside the US, also opposed the hidden like and RT counts, but for a different reason. Japan-based user researcher Kiyo Yamauchi explained that some Japanese users actively avoid engaging with popular replies to avoid exposure that would attract attacks or abuse.

With the feedback in mind, Haider challenged the team “to think about that user need to understand which tweet is more important or worth my time, and see if there are other ways we can solve that, other than numbers.”

Jack Dorsey, Twitter’s CEO, has been outspoken about removing engagement metrics, because of how they encourage users to be outrageous in order to rack up more likes, retweets, and followers, and prompt readers to look for them. In an August 2018 interview with the Washington Post, Dorsey said, “The most important thing that we can do is we look at the incentives that we’re building into our product. Because they do express a point of view of what we want people to do — and I don't think they are correct anymore.”

Haider and her twttr team are hoping to “nudge” people’s behavior in another way. Their hypothesis: Making the design for replies as minimal as possible, in addition to revealing how the conversation’s participants are related to you, may encourage people to read the entire back-and-forth before they react.

“We have this opportunity to learn about how not having [likes and retweets] could potentially change how people read things,” said senior product designer Lisa Ding. “Does it make you read something that you maybe would have guessed to be popular but actually isn’t that popular? How does that change the way you interact in a conversation? That’s super interesting.”

In its early years Twitter optimized for engagement, which engagement features (replies, and the like and retweet buttons) and metrics (number of followers, likes, retweets, and replies) help to deliver. So now it’s trying to shift what it encourages people to do.

Twitter is not alone in this. Tech leaders across the industry are rethinking the role of their platforms’ incentives, in response to mounting criticism that technology platforms do more harm than good. Instagram is running a test where like counts are hidden to followers, but are viewable by the post’s account holder. Head of Instagram Adam Mosseri told BuzzFeed News that the test wasn’t about incentivizing specific behavior but “about creating a less pressurized environment where people feel comfortable expressing themselves” and focus less on like counts.

For Twitter, part of the rationale behind running an external-facing prototype with experimental features, in full view of its competitors, is easing users into the new design. “We are fundamentally changing how Twitter works. … We need for people to have some exposure to it,” said Haider.

People typically don’t take kindly to changes, especially ones that come without warning. In 2009, Facebook users revolted so strongly to the introduction of the News Feed (which some groups called an “invasion of privacy”) that CEO Mark Zuckerberg personally responded, “Calm down. Breathe. We hear you.” So to avoid taking users by surprise with a big change, and instead of developing a product secretly inside of Twitter’s walls, Haider wants to take users along for the ride: “We need people who aren’t even in the program to read the press articles and think, ‘I am now mentally prepared for this change.’”

Haider's team is considering future features that may be even more controversial than hidden likes. Two ideas they're exploring: optional "presence indicators" that show people when you're online or typing, and being able to add a status that lets people know what you want to talk about.

There are many challenges with fixing Twitter, but the primary issue has to do with the form of Twitter itself. It’s an extremely complex product: Every reply is itself a tweet, and every tweet can be infinitely replied to. Conversations can be hard to read, let alone understand, and that misunderstanding contributes to a lot of the repetitive first responses to tweets, reply dogpiling, and knee-jerk reactions — like the kind that flooded Stone’s mentions — that fuel the platform’s outrage cycle.

One user, @matthewreid, replying to Stone, summed up the issues facing Twitter nicely: “A quick scroll through many of these replies illustrates what made this place I love so toxic. Bullying. Mob mentality. Insufferable knowitalls.” Twitter CEO Dorsey has admitted the same himself: “I also don’t feel good about how Twitter tends to incentivize outrage, fast takes, short term thinking, echo chambers, and fragmented conversation and consideration.”

“Like, imagine being in a room and talking to a billion people. It's chaos.”

“Having conversations that anyone can see and anyone can participate in is a really awesome super power that needs to feel really simple despite its complexity behind the scenes,” Twitter product lead and Periscope cofounder Kayvon Beykpour told BuzzFeed News. "Like, imagine being in a room and talking to a billion people. It's chaos.“

To reduce the chaos, the twttr prototype is reimagining what Twitter could look like. “What are the mechanics that we allow you to do right at the surface versus one tap away? We are essentially rethinking paradigms that have been the case for 13-plus years,” Beykpour explained.

Much of Twitter’s efforts related to abuse and harassment are incorporated directly into the main Twitter app, but some concepts in twttr’s pipeline are in service of something directly related to harassment: trying to change the tone of replies. According to Dorsey, replies are one of the shared spaces where abuse happens the most on Twitter. In a potential upcoming feature, if you tap on an avatar while you’re reading a reply, a profile card showing more information about the tweet’s author appears alongside their tweet.

Haider explained, “If you can see who you’re replying to, then you may change the tone in which you reply. I know this anecdotally, when people tweet shit to me, and I respond, right? Imagine if in this reply state, you could actually see ‘oh, this person’s a father of two.’”

Beykpour acknowledged that the feature feels “tiny” but said Twitter is starting to “tug on this string” related to empathy: “How do you surface context around who this person is, but ideally also give you a little bit of empathy around who you’re talking to? It's harder to have an uncivil dialogue with someone that you know a little bit more about than if it was an anonymous face."

“It's harder to have an uncivil dialogue with someone that you know a little bit more about than if it was an anonymous face.”

He added, “Civility is one really important aspect of [healthy conversations]. It’s very difficult for people to feel like they can speak freely, if they don’t feel safe enough to speak in the first place.”

Twitter is investing a lot of effort into making the experience on its platform better and more delightful (hello, cherry blossom like button), but it still has a lot to overcome with abuse and harassment, as well as issues that don’t have a simple fix — like tone and, more generally, sexism on the internet. A product overhaul can’t change the primary source of harassment on its platform: its own users.

Like a lot of people, Tracy Chou, the CEO of Block Party, a company working on solving abuse and harassment online, has herself been subject to much targeted harassment on Twitter. “Group direct messages are the new spam vector. One of the group threads in my DMs looked like it was a bunch of college students, white men, who seemed to know each other, and were talking about how easy it would be to murder me,” Chou told Buzzfeed News.

If you have open direct messages, you can’t restrict specific accounts from sending you DMs unless you block them, which Chou says, is an example of a feature designed to protect users that doesn’t actually work in practice. “Blocking is aggressive and visible to the other person. That sometimes will set them off and cause them to harass you more, or use it as a trophy,” she said.

Chou also explained how retweeting and quote-tweeting are product features that can easily be turned into tools of abuse — and counter-abuse: “If some asshole says something racist, sometimes I’ll quote-tweet them, and say “no.” My followers will fight my battle on my behalf. But [quote-tweeting] can also be used to target harassment by people who have a lot of followers and want to sic their followers on a specific individual.” In 2016, conservative writer Milo Yiannopoulos was banned for inciting his followers to flood Ghostbusters actor Leslie Jones’ Twitter account with racist and demeaning mentions.

For users like Chou, the twttr program hasn’t done much to improve their Twitter experience so far. “I mainly find it harder to read replies,” Chou said. She added that the user image and username size have been minimized in the prototype, which isn’t helpful when trying to identify replies from known trolls. A Twitter spokesperson said the twttr team is testing different sizing and presentation for avatars and display names.

“Everything these companies do, at first, is driven by the short-term desire to stake a small share of the attention economy and to engage users just long enough to attract early funding. Only later does the medium view start to matter, and the long view doesn’t matter at all until very late in the game,“ explained Adam Alter, author of Irresistible, a book about the rise of addictive technology. “Most of the changes Twitter and other platforms are making now are fairly small. They aren't going to change usage patterns much — but they're a step in the right direction.”

As someone who has used twttr for over two months, the new design does feel like a change for the better. In replies, the eye-catching magenta “author” label makes it easy to scan for additional comments from the tweeter. The “family tree” lines denoting different threads are useful. If there are two “debate me” trolls shouting at each other in one thread, you can easily scroll down, gloss over the entire back-and-forth, and jump into the next one. In a future iteration of twttr, you’ll even be able to collapse conversations more easily.

But the twttr effort isn’t just about improving the product experience. There’s a business motivation, too. Haider thinks that the final changes, if and when they are rolled out to the main Twitter app, will ultimately lead to more tweeting: “Obviously with a better conversational experience, people will use [Twitter] more and they’ll get more value out of it, which is what we’re trying to aim for.”

While Twitter has been consistently profitable since early 2018, the company said in the first quarter of the year that its number of monthly active users declined to around 330 million, down 6 million from the same time last year, and said that it would stop reporting monthly active users altogether. To keep users on the platform — and advertising revenue flowing — the company needs to figure out how to make its service a nicer, better place for people to spend their time. In the most recent earnings call, Dorsey called the ability to have conversations on Twitter the platform’s “differentiator” and cited the twttr prototype as progress.

As the internet’s free, most popular platforms — Facebook, YouTube, Twitter — now know, people will use products in ways their inventors didn’t intend them to be used, and with software designed to “scale,” its downsides aren’t apparent until millions of people are using it. Twitter is now trying to undo the features that caused unseen, unanticipated effects — misinformation, trolling, tribalized outrage — by going back to basics.

Whenever you’re in a room with a lot of people talking at once, people raise their voices, so they can be heard. As more people arrive, it becomes cacophony. This is, essentially, what has happened on Twitter: The volume of the conversation has been getting louder and louder for 13 years. Beykpour and Haider’s solution is toning down the background noise, and helping people focus on the conversation right in front of them. But the longer a problem exists, the more intractable it becomes. Which means it is ultimately up to Twitter’s hundreds of millions of users to decide whether it is even possible to have a real conversation amid its din, or if the only answer is to shout louder. ●