1. The New York City Police Department explicitly prohibits the use of chokeholds.

The NYPD's Patrol Guide includes very specific regulations on the use of force. The regulations are meant to prevent unnecessary escalations and to ensure that officers don't hurt civilians in their interactions.

The latest edition of the Patrol Guide defines and explicitly prohibits chokeholds (the emphasis is in the original):

Members of the New York City Police Department will NOT use chokeholds. A chokehold shall include, but is not limited to, any pressure to the throat or windpipe, which may prevent or hinder breathing or reduce intake of air.

2. But some cops still use them — sometimes to disastrous consequences.

View this video on YouTube

The NYPD's use of chokeholds came into the national spotlight last summer after cell phone video footage of Eric Garner's death went viral.

Garner died July 18 after NYPD Officer Daniel Pantaleo put him in a chokehold while trying to arrest him on suspicion of selling individual cigarettes. The city's medical examiner ruled Garner's death a homicide.

Pantaleo denied breaking the NYPD's rules during his encounter with Garner, calling the act of putting his arm around the suspect's throat "a wrestling move." He was later cleared of all wrongdoing by a grand jury.

Together with other incidents across the country in which unarmed black men were killed by police officers, Garner's death sparked widespread protest in New York City and elsewhere.

The protests, which brought tens of thousands to the streets, became the biggest crisis yet for the year-old government of Mayor Bill de Blasio, who had campaigned on a platform of reining in police excess.

3. So New York City's brand new Office of the Inspector General did a review of 10 recent chokehold cases.

The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) is a new agency created by the de Blasio administration. It oversees the NYPD and is supposed to serve as an outside watchdog for the police department.

On Monday, the OIG released its first report on NYPD practices. It is a review of 10 recent cases in which the Civilian Complaint and Review Board (CCRB) — the agency that deals with accusations of wrongdoing against police officers — determined that NYPD officers used chokeholds.

The review does not include the Garner case, which at the time was the subject of a criminal investigation. It also notes that the OIG does not pass judgment on whether the allegations against the officers are true, and cautions against generalizing its conclusions:

No conclusions can or should be drawn about the prevalence of chokeholds in NYPD encounters from such a discrete and limited sample size. Nor can one credibly extrapolate an explanation for why police officers use chokeholds, notwithstanding their ban in the Patrol Guide, from a review of these ten cases.

4. The review found that the process of figuring out whether a cop deserves to be punished is very convoluted.

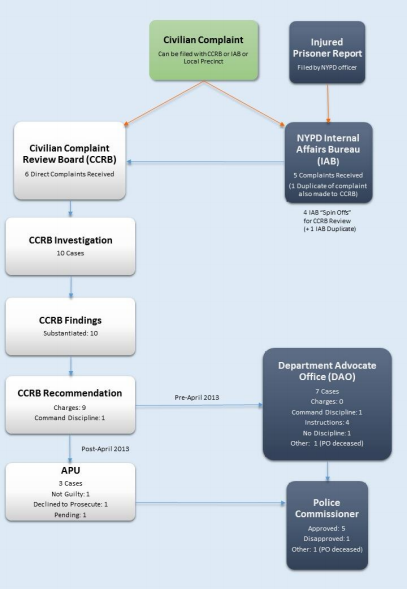

There are two avenues for filing a use of force complaint against an NYPD officer — one through the Internal Affairs Bureau, the other through the CCRB. The Internal Affairs Bureau forwards all the complaints it receives to the CCRB, which then investigates.

If the review board finds that the allegations are substantiated — as it did in the 10 cases reviewed by the inspector general — it then issues a disciplinary recommendation.

Until recently, the CCRB's recommendation then went to the Department Advocate Office, an NYPD unit, which would then review the civilians' findings and issue its own recommendation.

The Department Advocate Office's recommendation would then go to the police commissioner — the appointed civilian head of the NYPD — who would make a final decision.

5. The former police commissioner often declined to discipline officers who allegedly broke the department's rules.

Until recently, the police commissioner had final authority on many disciplinary cases involving cops. During the period reviewed by the OIG, when Michael Bloomberg was mayor, the position was occupied by Raymond Kelly.

The OIG report found that Kelly's office pardoned two police officers accused of using chokeholds.

In the first case from 2008, a 19-year-old woman was arrested after she tried to walk away from the principal of her high school in the Bronx. According to the CCRB complaint, a police officer "threw her against the wall and grasped the front of the complainant's neck."

Based on video of the incident, the CCRB recommended that the police officer be given "administrative charges," the most severe form of disciplinary action in the NYPD, which can include termination. But Kelly "directed that no disciplinary action be taken," the OIG report said.

In the second case, also from 2008, a 15-year-old boy was allegedly placed in a chokehold at a Bronx police station while being detained on suspicion of armed robbery.

According to the CCRB, the teen was handcuffed to a metal bar when a police officer approached him from behind, "put his arms around his neck, and choked him."

Again, the CCRB recommended administrative charges, but Kelly and the Department Advocate Office agreed that no disciplinary action should be taken.

6. As a result of the review process, many officers who break the NYPD's rules don't face serious consequences.

None of the 10 officers involved in the cases under review received serious sanctions, even though the CCRB recommended them in all but one of the cases.

One of the officers lost five vacation days and three officers received "instructions" — the least severe form of discipline, which consists of retraining.

Three other officers received no discipline whatsoever.

Of the remaining three cases, two are still pending. The tenth officer died before his case could make its way through the NYPD review process.

In April 2013, the process changed and the CCRB was given the authority to prosecute cases for which it recommended administrative charges. Two such cases remain under review.

7. So what is the solution?

The OIG issued a number of recommendations to help the NYPD assess its disciplinary process. They boil down to suggesting that the CCRB and the Internal Affairs Bureau communicate better with each other, and that decisions by the police commissioner be more transparent.

Speaking at a news conference Monday, current Police Commissioner Bill Bratton said he has yet to receive a "so-called chokehold report" since he began his tenure.