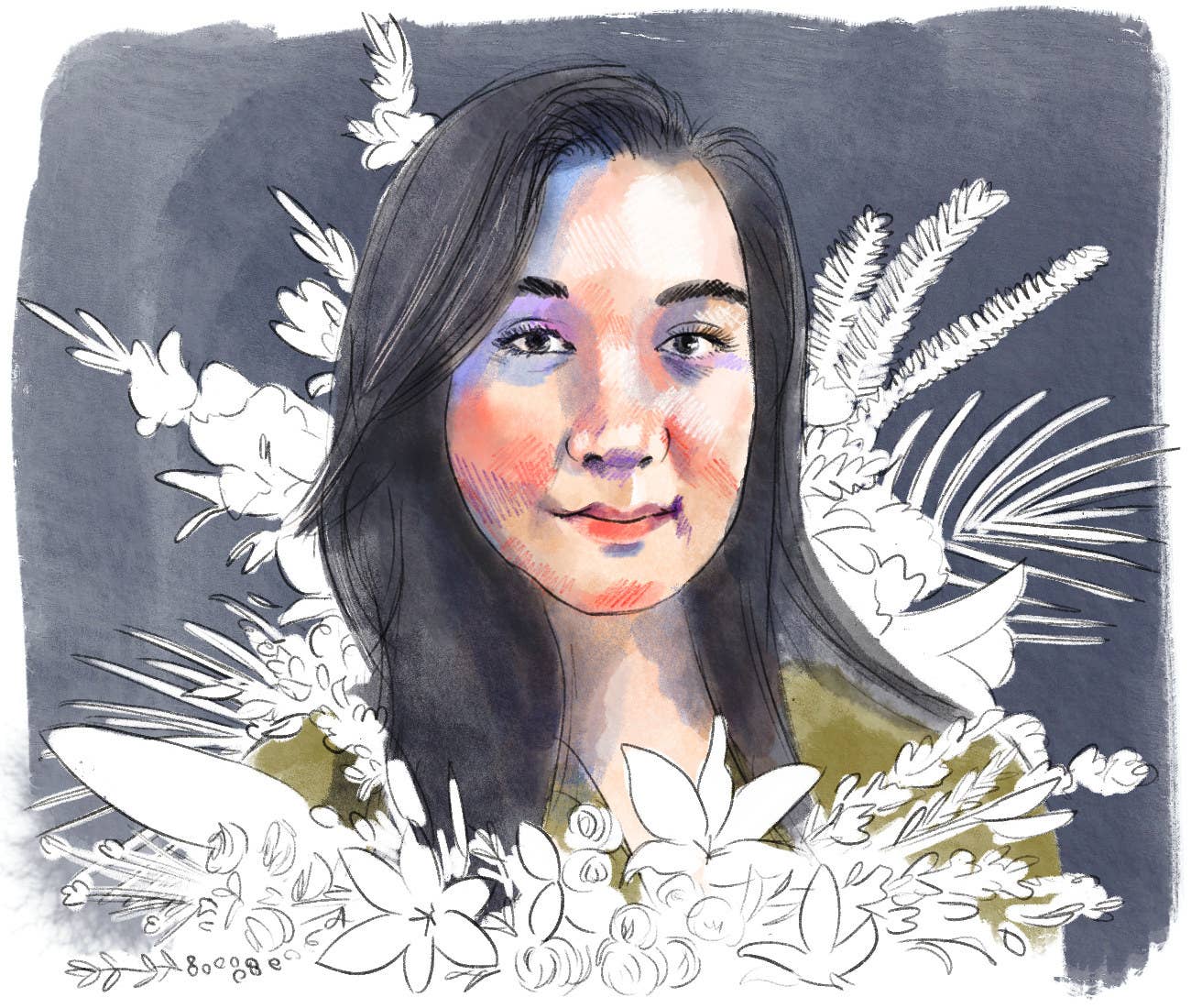

Nearly everyone who knew Acey Morrison has a story about the impact she had on them: how she pushed them to be their best selves or helped out when they needed a hand. Morrison’s cousin, Casey Morton, moved into her Rapid City, South Dakota, apartment two years ago and found a counselor and confidant in Morrison. As a Native American trans woman, she was one of the few people in his life who could understand what it was like to be LGBTQ in a Republican-leaning state. “I get called ‘fag’ all the time because of how I identify myself — as a proud gay man and also Native American,” Morton told BuzzFeed News. “It’s so close-minded here.”

When Morrison’s nephew, Dale Two Eagles, ran out of gas a few years ago, his aunt was the one who came to his rescue — even though she had a busy day of errands to run. Morrison’s childhood friend, Cheryse Hawkins, credits her with helping her get sober after she slipped into addiction in her early 20s. With Morrison’s encouragement, she completed her GED, enrolled in Job Corps, and received an associate’s degree in child development. Hawkins has now been sober for seven years, but after they fell out of touch, she never got the chance to say thank you.

“I never got my moment to tell her, ‘Hey, I changed my life, and it was because of you.’” she told BuzzFeed News. “I find comfort knowing that now she knows — especially us being Native American and her going to the spirit world. I feel like she knows, but I wish I had the opportunity to tell her.”

Morrison, who had just turned 30 in July, was fatally shot in a Rapid City mobile home on Aug. 21, making her the 30th trans person to die violently in 2022. By the end of the calendar year, that total would increase to 38 — among the highest numbers on record since the Human Rights Campaign first began tracking violence against trans Americans in 2016. At least 29 of them were trans women of color. But in spite of the violence of Morrison’s death, it has not been declared a homicide, and no one has been arrested almost six months later. Her mother, Edelyn Catches, told BuzzFeed News that the man who shot Morrison described it as self-defense, which her family and friends dispute. The Pennington County sheriff’s office says the case remains under investigation and declined to answer questions from BuzzFeed News.

“It’s just hard to accept it, to the point where all I want is justice. I want someone to pay for it.”

Morrison’s death is yet another example of the routine violence faced by Two-Spirit people — a term used by many Native communities to describe trans and gender nonconforming people — following several prominent killings in recent years: Jamie Lee Wounded Arrow in 2017, and Poe Black and Whispering Wind Bear Spirit in 2021. Wounded Arrow, who also lived in South Dakota, was fatally stabbed seven times by Joshua Rayvon LeClaire, who was sentenced to 65 years in prison after pleading guilty to the murder. And although in recent years there’s been increased awareness around missing and murdered Native American women, the killings of Two-Spirit people remain an invisible epidemic. Advocates said there’s almost no hard data validating how pervasive this brutality is, and they believe the deaths of Native trans and gender nonconforming people are widely undercounted.

Family members and close friends worry that as in the cases of other Native people whose lives were taken too soon, no one will be held accountable for Morrison’s death. They are still adjusting to life without her. “Her being gone is taking a big toll on me,” Morton said. “It’s just hard to accept it, to the point where all I want is justice. I want someone to pay for it. I helped her get lowered into the ground, but it still hasn’t registered that she’s gone. Still to this day, I open up my phone and I snap her something. It hasn’t hit — that harsh reality that she’s not going to respond.”

Morrison was dead for 16 hours before her family members said they were notified by police, even as they frantically searched for her. They first realized something was wrong when Morrison failed to drop off her 2-year-old nephew, of whom she had recently gained custody, at a babysitter’s house around noon on Aug. 21. By 2 p.m. that day, Morrison should have clocked in at the local hotel she managed, and when she never showed, it triggered warning bells. Her loved ones said she never missed a shift — even when she was sick — and often picked up extra hours at work. It was Morrison’s tireless work ethic, often doing the jobs of several people, that allowed her to work her way up from housekeeping to the front desk and eventually management.

Morrison’s family members called the Pennington County sheriff’s office throughout the day, but law enforcement officials told them they had no knowledge of her whereabouts. After finishing her workday at the local jail, her sister, Raena Cross Dog, drove to her mother’s home to await further information, which arrived in the form of a visit from the Oglala Sioux Tribal Police around 11 p.m. Tribal police said they had been asked to deliver the news of Morrison’s death on behalf of Pennington County and, though Cross Dog pleaded for more information, the officers merely expressed their condolences. “I just remember slamming the door, but I think I blacked out because I was laying on the floor and my son’s dad was blowing in my face,” she told BuzzFeed News. “I checked on my mom, and my brother was holding her and they were all crying.”

Since then, Morrison’s family has been left with more questions than answers as they attempt to piece together the last moments of her life. That night, Morrison drove to a trailer park on the northern outskirts of Rapid City to meet up with a man that friends and family said she had initially connected with on the gay dating and hookup app Grindr. Phone records obtained by BuzzFeed News indicate that she’d spoken to the same unlisted number four times in the 36 hours before her death, beginning with a 2:30 a.m. incoming call on Aug. 19 that lasted for just two minutes and concluding with a nine-minute conversation the following day at 11:51 p.m., shortly before sources believe she drove to the residence where she was killed.

Family members said the sheriff’s department informed them that Morrison and the property owner decided not to go to bed together after a brief conversation over drinks, but he refused to let her drive home, asserting that she was too inebriated to get behind the wheel. He directed her to sleep on his couch instead, and the man claimed that she refused to leave the following morning, resulting in a struggle over a gun. It accidentally fired, family members said investigators told them, and she was fatally wounded. The property owner did not respond to multiple requests for comment from BuzzFeed News, but local news reports said he has been cooperating with the investigation.

Morrison’s loved ones said that explanation doesn’t match up with the person they knew or the little information they do have about the incident. While the man claimed that the shooting was in self-defense, Morrison was allegedly “bruised and beaten” in photos of her body shown to the family 10 days later. “He said Acey was trying to attack him on his property,” Muffie Mousseau, a local Two-Spirit activist who has been working with Catches, told BuzzFeed News. “That’s the story that’s out, but that’s not what really happened. How did Acey get beaten up between 1 and 7 a.m.?” Morrison was shot directly in the chest with a 12-gauge shotgun, Mousseau said, which she believes does not suggest that the gun was accidentally triggered during a physical altercation.

Catches added that Morrison would not have stayed overnight in a stranger’s home, even if he had attempted to stop her from leaving. That is part of the reason Catches said that her daughter had a DUI on her record, for which she recently got off probation. “Acey will not sleep in someone else's house,” Catches said. “I’ve seen Acey drunk. When there’s arguing, the first thing is she would try to defuse the situation. She turns around and leaves. She’s not the type to fight.”

Among the many other unanswered questions from that night include the brief disappearance of 2-year-old Orlando, who was missing for 24 hours before he suddenly turned up at Morrison’s apartment. Cross Dog said that family members visited the residence on three separate instances searching for him before he was found on the evening of Aug. 22, sitting awake in his crib. He’d been fed, his diaper was changed, and he didn’t show any signs of dehydration, even though the heat topped 97 degrees that day. Morton believes that someone was babysitting Orlando and brought him home, although he’s not sure who that person might have been.

“Acey would never leave him,” he said. “He was her life, her love, her everything. When she got Orlando, that made her world. She wanted to be a mom, and everything circled around this little guy. She would have never left him unoccupied, unless she knew that someone was going to be there. I personally think there’s someone that knows the story that doesn’t want to be in trouble, that has more information to give us. Someone took care of Orlando but don’t want to say nothing.”

Aside from the preliminary information they received from the sheriff’s office, family members said they’ve gotten few updates. Catches said that Detective Cameron Ducheneaux, the investigator assigned to her daughter’s case, promised to check in every week, but she said she has heard from him only a handful of times since August, despite calling him multiple times a week. When Ducheneaux arranged to meet with Catches at his office in late December, she worried that he was preparing to shut down the investigation, but instead he stood her up, she said. When she arrived at the station, Catches said she was informed that he went home early for the day, and multiple calls to his phone were not returned. Ducheneaux declined to comment on this story, also citing the ongoing investigation.

“I just miss her laughter. If I felt down, she would make a joke about whatever the situation is and get me to laugh.”

Now Morrison’s loved ones worry that the sheriff’s office may be attempting to pin the blame for her death on the woman herself. While investigators haven’t asked family members for information about her relationship to the shooter, Catches said they have zealously dug into her daughter’s past — contacting former coworkers and even people with whom she went to high school. But Catches said that finding someone with a bad word to say about her daughter will prove difficult.

“All her friends I talked to, they say, ‘Oh, she inspired me so much to keep on going and better my life,’” she said. “Now they message me and they cry. They miss Acey. I tell them, ‘Whenever you’re down, do what I do. I think about what Acey would have told me: Snap out of it, Mom. Step back. Take time to look at it and then take care of it a little at a time.’ I just miss her laughter. If I felt down, she would make a joke about whatever the situation is and get me to laugh. When she laughs, it’s just that laughter that lifts your spirit up.”

Acey Morrison’s best friend, Rowena Blacksmith, said Morrison taught her how to speak up for herself and fight for what she wanted in life, whether that was shutting down middle school bullies or meeting their mutual weight loss goals. It was Morrison who encouraged Blacksmith to go back to college last year when she was unsure of whether she could handle the responsibility of raising three children while juggling her course load. “She was the one who had goals set and knew what she wanted to do,” she told BuzzFeed News. “She was always the humorous one, and I was the shy type. She was the one who got me to get out of my shell and express myself more.”

Seeing how little seems to have been done about Morrison’s killing has made it difficult for Blacksmith to cope. Blacksmith visits her friend’s gravestone as often as three times a week, sitting for hours with a soda and assorted snacks that Morrison liked to eat. “The fact that she’s getting no justice breaks my heart and makes me relive that day when I found out,” she said. “I felt so clueless and helpless. I’m still trying to figure out life without her.”

Although Morrison’s death gained national attention after she was included in HRC’s regularly updated index of trans people who were killed, it initially drew little notice in South Dakota. When her name was read aloud as part of a Trans Day of Remembrance event in Rapid City on Nov. 20, it was news to many of those present. Some in the crowd gasped. “It was a shock to some people,” Toni Diamond, a board member for the Black Hills Center for Equality, told BuzzFeed News. “We didn’t know there was somebody locally that had lost their lives.”

Part of the reason that few locals knew about the killing is that initial media reports about the shooting either misgendered Morrison or didn’t use pronouns to describe her at all. The first — and to date, only — article published in a South Dakota publication that mentions she was transgender ran in the Argus Leader in November, almost three months after her death. This is a common phenomenon following the deaths of trans people: In a 2020 report from Media Matters, nearly two-thirds of trans individuals killed that year (62%) had been deadnamed in media reports and referred to by a gender that didn’t match their lived identity.

“We go missing in lots of different ways: physically and then also through data.”

But according to advocates, understanding what happened to Morrison means recognizing not only her trans identity but the vulnerable intersections at which she lived. A 2016 report found that Native Americans were more likely than any other group to be killed by law enforcement, and Rapid City, in particular, has a poor track record in how it treats Native populations. At least 43 children died while attending the Rapid City Indian School, a boarding school run by the federal government that was shut down in 1933 following repeated and unchecked disease outbreaks. They were buried in unmarked graves on a hillside near the former campus, which is soon to be the site of a memorial. In December 2014, the police killing of Allen Locke, a 30-year-old Lakota man, drew protests after the shooting was ultimately declared justified. No charges were brought against the responding officer.

More recently, the city’s Grand Gateway Hotel was sued by the Department of Justice in October 2022 after its staff allegedly refused to book rooms for Native customers following a shooting that took place at the establishment. Before the alleged service refusal, the DOJ said co-owner Connie Uhre posted on Facebook that she cannot “allow a Native American to enter our business.” “The problem is we do not know the nice ones from the bad natives, so we just have to say no to them!” reads a screenshot of the Facebook post included in the lawsuit’s complaint. Attorneys for the hotel and Uhre have denied any discriminatory practices and that she made the Facebook post, and the lawsuit remains ongoing.

Mousseau, cofounder of the Native advocacy group Uniting Resilience, said the mistreatment of Indigenous people is pervasive in Rapid City, particularly for members of the LGBTQ community. She estimated that she has been stopped at least 11 different times by police since 2019, including being “taken out, put in handcuffs, roughed up, jerked around, and pushed around.” When she and her wife walk into a store, Mousseau said they can feel all eyes on them, and they make sure to check the lug nuts on their car any time they go out. They also have locks on their gas tanks and cameras outside their home.

“It’s like back in the 1920s here in Rapid City,” she said. “I guarantee you: If you have brown skin, you get off the airplane, and you walk to your taxi, you’re gonna know that you’re a different color. That’s a warning I give to a lot of minorities: You don’t want to come to Rapid City because it’s Racist City here.”

Despite the layers of oppression that LGBTQ Native people face — whether in Rapid City or elsewhere — hard data on the subject is scarce. Research shows that 84% of Indigenous women have been targeted with violence at some point in their lives, and they account for an estimated 28% of missing persons cases in South Dakota, despite making up just 4% of the state’s population. The murder rate for Native American women is 10 times higher than the national average. But while activists have successfully pushed for the conversation on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls to include Two-Spirit individuals — leading many to adopt #MMIWG2S in social media posts — but it remains unclear how many of these victims are LGBTQ. The National Crime Information Center has recorded 5,700 cases since 2018, but the federal database does not indicate how many identified as trans or gender-diverse.

Charlene Aqpik Apok, executive director for Data for Indigenous Justice, said there is no “clean data source” that comprehensively examines the violence that LGBTQ and Native people face in their daily lives. “The data systems aren’t set up to capture our identities, whether it’s as Indigenous peoples, queer folks, or nonbinary people,” she told BuzzFeed News. “We go missing in lots of different ways: physically and then also through data.”

While the only information that activists have is anecdotal, Apok said the violence against these populations is so pervasive that it’s difficult to even talk about. “That's living data, and it’s very viscerally ingrained in our bodies,” she said. “People that I love very much have been really harmed, and the amount of losses that we see in our families and our communities is devastating.”

As advocates work to raise greater awareness about the hidden violence targeting LGBTQ and Native people, Morrison’s mother just hopes to keep her daughter’s memory alive. Catches said that she owed so much to Morrison, who took her to physical therapy appointments and made sure that she was eating healthy. Morrison was always giving her mother extra money — even if she was down to her last $20 — and even helped Catches get a job when she was struggling. The 56-year-old is raising Orlando now that Morrison is gone, although it has been extremely tough without her daughter there to help.

For weeks after Morrison’s death, Catches barely slept and has suffered from extreme chest pain, but she was able to finally find some peace after being invited to a local sweat lodge. Catches elected to sit outside the door, praying, until the medicine man urged her to come in, saying that her daughter wanted to speak to her. Typically during these ceremonies, the medicine man translates on behalf of the deceased, but in this case, Morrison addressed her directly, she said. She told Catches that she worried for her but assured her mother that she was safe now. “I gotta go,” Morrison told her. “I love you, Mom.” Morrison left before her mother got to say the thing she had so badly wanted to tell her: “Thank you for being part of my life. I’m just glad I was your mom.”

As Catches and her community work to move forward, there’s one conversation that she still wants to have: a discussion with the man who shot her child. “That guy needs to admit to what he did. He needs to go to jail,” she said. “He killed Acey. I want him to live forever, and I want him to fucking suffer.” ●