Sometimes, I’ll take a shower in the middle of the day because I need to stand alone and in silence without feeling guilty. Without drawing attention to myself. I don’t want anyone to misunderstand. Especially my children.

The noise that words make in my professional worlds as lawyer, law professor, and writer have brought me to a partial deafness. I have to lean forward and tilt my head to one side if a student at the back of my class asks a question. There, I will ask her to stand up and, “Project!” I'll say. It’s “an exercise of elocution.” But it’s me. My growing weaknesses.

I believe that language is an argument. Even a word is a negotiation — is he a terrorist or a gunman, undocumented or illegal. Even our silences speak. They also allow us to be present.

My beautiful daughter was born typically abled, and my extraordinary son was born with a rare metabolic condition called SSADH. He is effectively silent. “Nonverbal” is the clinical term. Nine years old now and he speaks only two dozen words, commands a few sounds. There is no cure. The same is true of aging. The only difference between us is that I’m growing into my faults, while he’s always known his. I tell him that this is the way God was pleased to make us, and even this way, we are still whole.

My son’s condition causes him muscle weaknesses and mental delays. He was late to walk, just over 3 years old, and at 6 he learned to make a running motion with his upper body while shuffling his feet. And this “run” we cheer as complete. As we do with his sign language. His muscle weaknesses affect his hands so his signs only model completeness. But communication is more than words, more than signs, and if we’re lucky, it’s a deeper connection that exists in the pauses. It is a glance, a breath, a touch.

I love watching him walk to school through my car window, holding hands with his school aide. There I exist in his pause. He’ll look back at me and his silence will speak: “I'm going to school, Mom. Look how strong I am. How big I’ve grown.”

Some days, when I give him something he’s been waiting for — a balloon, my phone, the remote control, a song on the radio — his eyes will widen and he will smile a silent thank you. And in those instances I can see him again. In those pauses we communicate. “Yes, I know it’s your favorite,” I’ll say. “And yes, it’s all for you.”

So many of these moments are our moments — mine and his. Writing this out now is an exposure. To be honest, it makes me feel off. Like exposing some secret and not knowing how the audience will receive it.

When my son was born, I immediately knew something was wrong. It was within days of his birth. He wasn’t behaving the way my daughter had, born the year before. He wouldn’t lift his hands to his face, smile as much. I took him to his first doctor’s appointment a week after he was born and said, “There’s something wrong with my baby.”

My pediatrician checked my son over and assured me all was well. I was back two days later, then the next week, and the next week, each time with the same complaint, “There’s something wrong with my boy.”

I knew what depression was. This was different. I was afraid my son would die.

Eventually I was told “jaundice,” specifically jaundice from breastfeeding, and that I should stop breastfeeding — but I wouldn’t stop. Then when the jaundice cleared for some unknown reason and I lied and said I’d stopped breastfeeding, I was told nothing was wrong with him. And every other frantic visit after then, I was told nothing was wrong. Then finally, I was told that perhaps something was wrong with me. Postpartum depression — nothing to be ashamed of. Except I knew it wasn’t true. I knew because I had been depressed before, before I had children. I remember hearing these words, my words so clearly: “If I walk out into the middle of the busy intersection — tires screeching, glass breaking, metal hitting bone — we would all be better off. The poor driver would look through the mosaic of her windshield and think that what she hit was nothing. She’d be right. My family would be spared of me. And my husband would say I was an angel.”

I knew what depression was. This was different. I was afraid my son would die.

After a particularly fear-filled night, I went back to my pediatrician’s office. She was on vacation and another doctor, a retiree, was filling in for her. I sat in the waiting room with my son wrapped in my arms, angry that I’d have to explain everything to this new doctor. When I got into the exam room, Dr. Goldfarb, close to 70 years old, smiled and I said my same mantra, “There’s something wrong with my baby.” But Dr. Goldfarb didn’t give me the patronizing smile I had grown accustomed to. He asked about my son’s symptoms, asked if he could hold him, asked if he could lay him down on the exam table, asked if he could run a non-evasive urine test.

The next day, he called and told me that he suspected a problem. That he’d like to run another test that required blood from me, my husband, and my son, and the samples would need to be sent to Europe — the only place that could perform the test for SSADH because of the rarity of the disease. At 3 months old, my son became the youngest patient to be diagnosed.

It was my son’s silences that taught me to listen. To the pauses, to what’s said and not said. They can save a life, or cost one. I was told by one of my son’s many doctors that the muscle weaknesses he has require him to learn things that most people take for granted: to pinch, to smile, to raise an eyebrow. Involuntary movements that could extend to muscles like the heart. It could forget to beat. When my son was sick, I wouldn’t put him down; something told me he needed to hear me breathe, he needed to hear my heartbeat. And when I had to go back to work, I asked my husband to do the same. “Don’t put him down. I’m not crazy,” I told him. “I know,” he said. At that point we had only been married for three years, after a six-month whirlwind London-to-L.A. courtship. “I know you,” he said.

There is communication in the pauses. Things that are not said, or haven’t been said yet. Or experienced. Things we learn to trust because something inside us tells us so. For me, that’s the still, quiet voice of God. I don’t think any of us are empty.

It is this voice that I trust even more because of my son. He is a gift. He’s taught me how to hone some of the most important skills that a human being can have — love, compassion, service, and listening to the pauses. To be quiet and present. In his silences, he’s taught me more about language than law school and writing programs and living before him. Professionally, as a lawyer and as a teacher, and artistically, my goal has become more clear because of him – to give voice to the voiceless. They are our teachers. They are my son.

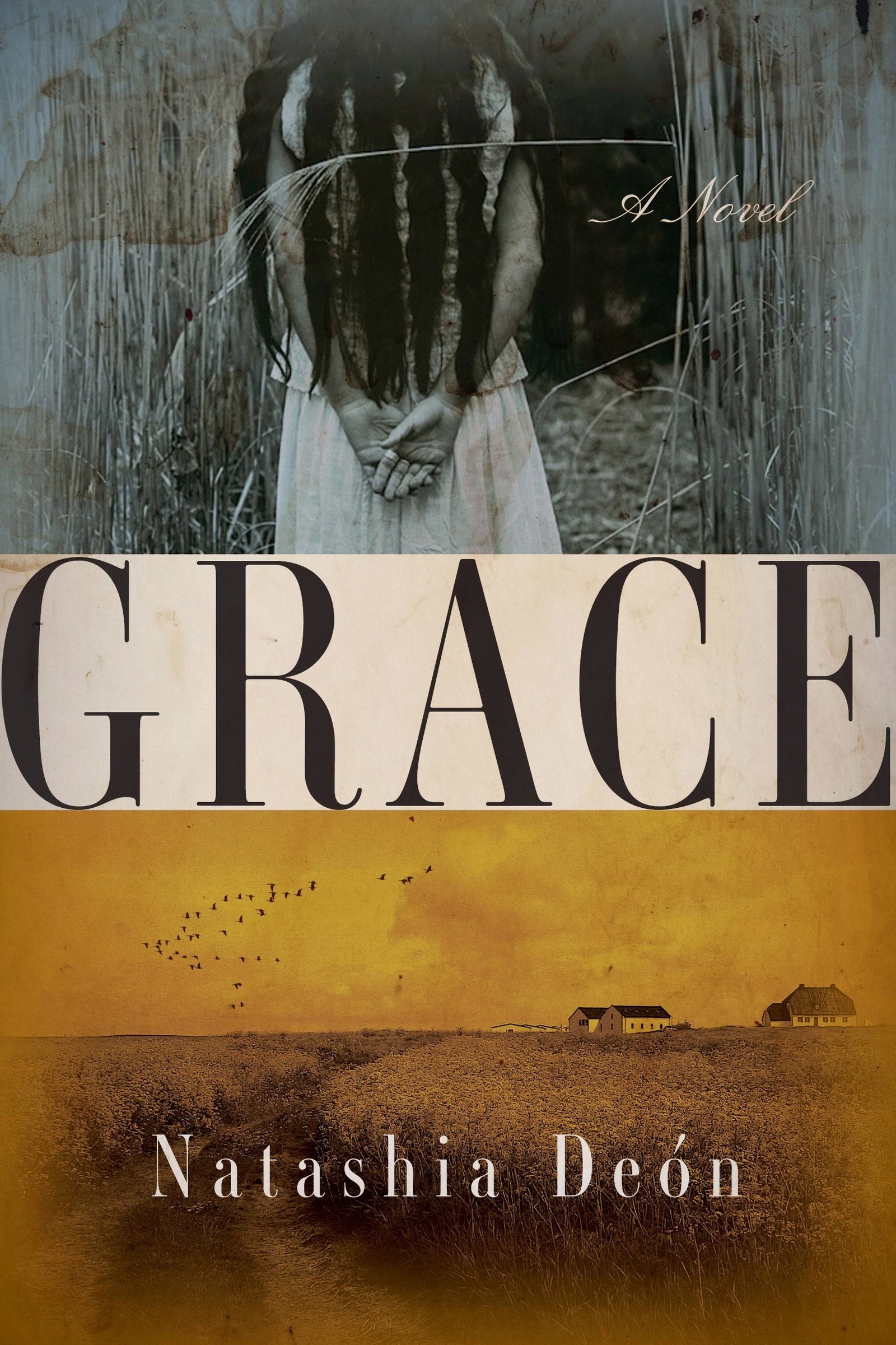

Natashia Deón is the author of Grace (Counterpoint Press), which earned her a PEN Center USA Fellowship. A Los Angeles attorney, mother, and law professor, she also produces the popular L.A. reading series Dirty Laundry Lit. Her writing has appeared in American Short Fiction, The Rattling Wall, The Rumpus, B O D Y, The Feminist Wire, and other places.