My mother is flying. She is smiling, her slender arms undulating as if they are wings, as if she is a bird. It is high summer, 1984. Morris Day and the Time play on the radio. The song — her new favorite — is “The Bird.” She dances as if she’s free to soar like one. And finally (Squawk, Hallelujah!), she is. I have not seen her this untethered in years. She does not say it, but we are celebrating. Joel is in prison, nearly a yearlong sentence ahead of him, and she is, for the first time in ten years, free.

In this moment we are far from the night in the fall of 1983 when my mother put into action her plan to escape. “Put everything you want to take with you in the front of your closet and stacked on your dresser,” she’d said. “Don’t take the bus home from school. I’ll pick you up.” I needed no explanation. Perhaps I had seen it coming: not in her stoic face, the usual smile she offered me, but something unusual in her behavior during the preceding weeks.

She and I had spent very little time together during my years in high school, and so I did not know what to make of her sudden show of attachment to me, one evening, when I went to the kitchen to announce that I needed to walk up the street on an errand. Joel was sitting at the table, his long legs crossed, watching her wipe down the counter — his face angled so that he could regard her with his left eye, which seemed to bulge even more when he was angry. They seemed not to have been talking as I came down the stairs, or perhaps just speaking too quietly for me to hear them. It was a small gesture that struck me, something girlish in the way she cried, “I’ll go with you!” And how tightly she held my hand as we walked, swinging it a bit, as I’d done long ago, a small child skipping beside her.

The feel of her hand in mine might as well have been a conduit. Before I knew it I was telling her, at last, all the things I had been holding back for years. He torments me when you are not at home, I heard myself saying. I used to be able to stay in my room on Saturday mornings when you went shopping, pretending I was asleep until you returned. But now he just comes into my room and starts harassing me as soon as you leave the house.

It was not long after that, on a Monday evening in October, that she knocked on my door and came quietly into the room, her arms crossed as if she were holding herself as she spoke. I was lying on my bed, reading. When I think of this now, I hear only my own voice in my head — Put everything you want to take with you in the front of your closet and stacked on your dresser. Don’t ride the bus home from school. I’ll pick you up. I have only a visual image of her, the sound of her voice long gone each time the scene replays: I watch her move stiffly, thinner in her yellow bathrobe than she’s ever been, as she turns and walks back down the hall toward the room where I know he is watching TV, waiting for her.

I will go to sleep, I remember thinking, and when I wake I will never see him again.

I will go to sleep, I remember thinking, and when I wake I will never see him again. But then I did. Less than a week later, unable to find her, he came to the place he knew I’d be on a Friday night: the high school football game at Panthersville Stadium. I was down on the track that runs around the field with the other cheerleaders when he walked onto the landing from the doorway to the concessions stand. There were only a handful of people who knew what was going on — among them, my best friend and her father, who sat directly in front of me, a few rows up, watching to see if Joel would come. I can’t remember why we assumed that he would — perhaps it made sense that he would try to get a message to my mother in the women’s shelter he’d not yet been able to find.

I spotted him at the top of the stadium, in the doorway, and watched him — though I pretended not to — as he made his way down the bleachers. He had that wild look I’d seen before, his Afro misshapen and his left eye bulging from its socket, larger than the other. When he chose a seat just in front of my friend and her father, I could no longer pretend not to notice him, so I waved, smiling and mouthing the words, “Hey, Big Joe.”

Hey, Big Joe, I’d said to him. After that, he didn’t stay much longer.

Years later I would read in the court documents that he told his psychologist at the VA hospital he’d brought a gun with him, planning to kill me right then and there, on the track around the football field, to punish my mother. He hadn’t, he said during his trial, because I’d waved and spoken kindly to him.

I did not yet know how that scene would haunt me over the years — before I’d ever read his words — my gesture toward him some kind of betrayal of my mother.

[Watch Natasha Trethewey read from Memorial Drive]

Had I known it even then, known it in my body first, that something I’d done had changed the course of events? Had he killed me then, as he claimed to have intended, he would have been apprehended, convicted, and imprisoned. By smiling and speaking a greeting to him, I had unwittingly saved myself.

We only had two short months of respite before Joel made his first attempt to kill her, on Valentine’s Day 1984. That morning, I was in my room at the back of the apartment getting dressed for school when Joey knocked on the door. He’d been sitting at the kitchen table, eating his breakfast. “I just saw Mama and Daddy get in the car and drive away together,” he told me. I knew immediately something must be wrong, and I think he must have sensed it too, but I didn’t want to let on that I was worried. “OK,” I said. “Go back and finish your breakfast. I’ll take care of it.”

I called my grandmother first, then the battered women’s shelter. The woman on the phone listened quietly as I described what my brother had seen. “Maybe they just went somewhere to talk,” she said.

I was not happy with that response. I knew that the people at the shelter should know better and, this time, I wanted someone to respond in the right way to what I was saying, to do something.

“No,” I said. “My mother would never get in the car and go anywhere with him. Never.”

After the calls, I got Joey to the bus stop and then left for school. It’s odd to me that I don’t recall anything about being at school the few hours before I finally heard from my mother. I recall only the moment I saw her again that evening. She seemed tired and moved slowly, limping a bit. She winced when I hugged her.

DeKalb County Police Department

CASE NO. 84037377

STATEMENT OF: Gwendolyn Grimmette ADDRESS: 5400 Memorial Dr. Apt. 18D SEX: F

HGT: 5'73/4"

WGT: 117

RACE: B

Statement taken by Inv. H.P. Brown

DATE 21484

TIME 11:03

On February 14, 1984 at approximately 7:15AM I left my apartment and was about to get in the State car. Joel Grimmette Jr., my ex-husband, came from out of the bushes near my building and approached me near the state car. I asked him what he wanted. He said to talk and told me to get in the car. I refused. He hit me once about the head. I screamed. He hit me again and said he had a gun (what appeared to be a gun in the pocket of his jacket was pointed at me) and if I screamed one more time he would shoot me then. I tried to dissuade him by saying our son was watching out of the window and he turned and waved at him. Then he took the keys to the car, opened the passenger side, and forced me in. By then I saw that he had a knife. I told him it was illegal for him to drive a state car, but he wouldn’t listen. I asked where we were going; he said he wanted to talk to me and he would drive me to work. I asked how he had gotten there, but he wouldn’t answer.

He drove down Memorial. As we neared 285, I told him it would be quicker (to take me to work) to go straight down Memorial. He took 285 South to Covington Highway, exited, then turned around to get back on 285 North, and exited at Memorial. We drove down Memorial to the Cinema 5 theatre. He turned in there and drove back to my apartment. He told me to go in, call my office, and tell them I would be in, but in a 1/2 hour. He listened with his hand on the cord to disconnect if I said anything else. Then he told me to sit down—I did on the couch—and to remove my coat. During all of this time (it was now 7:50, he had to make sure my kids had gone to school before we came back) he was talking about hurting someone close to me: he named my daughter (not his daughter) and my mother. He said he had been following her, my daughter, (he had previously told me he was following me, too) and could shoot her anytime. He told me to go to the bedroom, and sit on the bed. I did. He struck me in the mouth, near the eye, and about the head several times with his fist. I began screaming. He hit me again in the kidney, said he would break my back if I didn’t shut up.

I was trying to reason with him, and he continued to say I couldn’t be trusted and that he should have killed me before I left him, etc. etc. Then he asked if I knew how I was going to die. I said no. He said it would be real peaceful, and took out a needle with clear liquid in it. He asked if I knew what it was. I said no. He began talking about me taking everything from him, and that he was now impotent. I took that as a cue and followed up, by suggesting that it wasn’t true, in order to buy some time. I told him he should not die (by then it was going to be a murder suicide).

He told me he had a key to my apartment and had been in. He proved it by reciting some personal mail he had read of mine. He lit a cigarette then, a skinny one. I asked if it were pot; he said yes. I asked when he had started smoking it; he indicated since I left. He pulled some string (bits of cloth) from his pocket and tried to tie my hands. We struggled, he hit me, threw me across the bed on the floor and kicked me.

At that point I became extra fearful. Because he admitted that the psychiatrist said he should stay in the hospital. He even said he had gone in Friday of last week, so he wouldn’t be around to “watch me.” I convinced him to have sex before he died. He did. Then I told him I wouldn’t want Joey to come home to that scene and he should take me somewhere else. He said I would run, but not to worry, he would “remove” my body. Then he took the needle and started pushing it in my arm. I was trying to convince him to get help, telling him over and over that I would work with him.

He refused, said he wanted the “easy” way out, that he would be dead by tomorrow and maybe we’d meet one day in the great beyond. By that time the policeman knocked on the door. I told him it was maintenance—that they would come in anyway — and grabbed my robe, and ran to the door with him telling me to wait, and opened it.

GWENDOLYN GRIMMETTE

After Joel’s conviction, the feeling of relief I’d had when we first escaped came back. This time he was no longer in our world. There would be no chance of encountering him on the street, no way that he could get to us.

For the first time in so many years, all the years they were married, my mother and I were growing close again — just as we had been when I was a small child our first few months in Atlanta. This is why, in the scene that comes back to me again and again, she is dancing and I am laughing and clapping along to the song. It is high summer, 1984, Morris Day and the Time on the radio, doing “The Bird.”

And, finally, my mother is soaring, her winged joy boundless and unfettered. ●

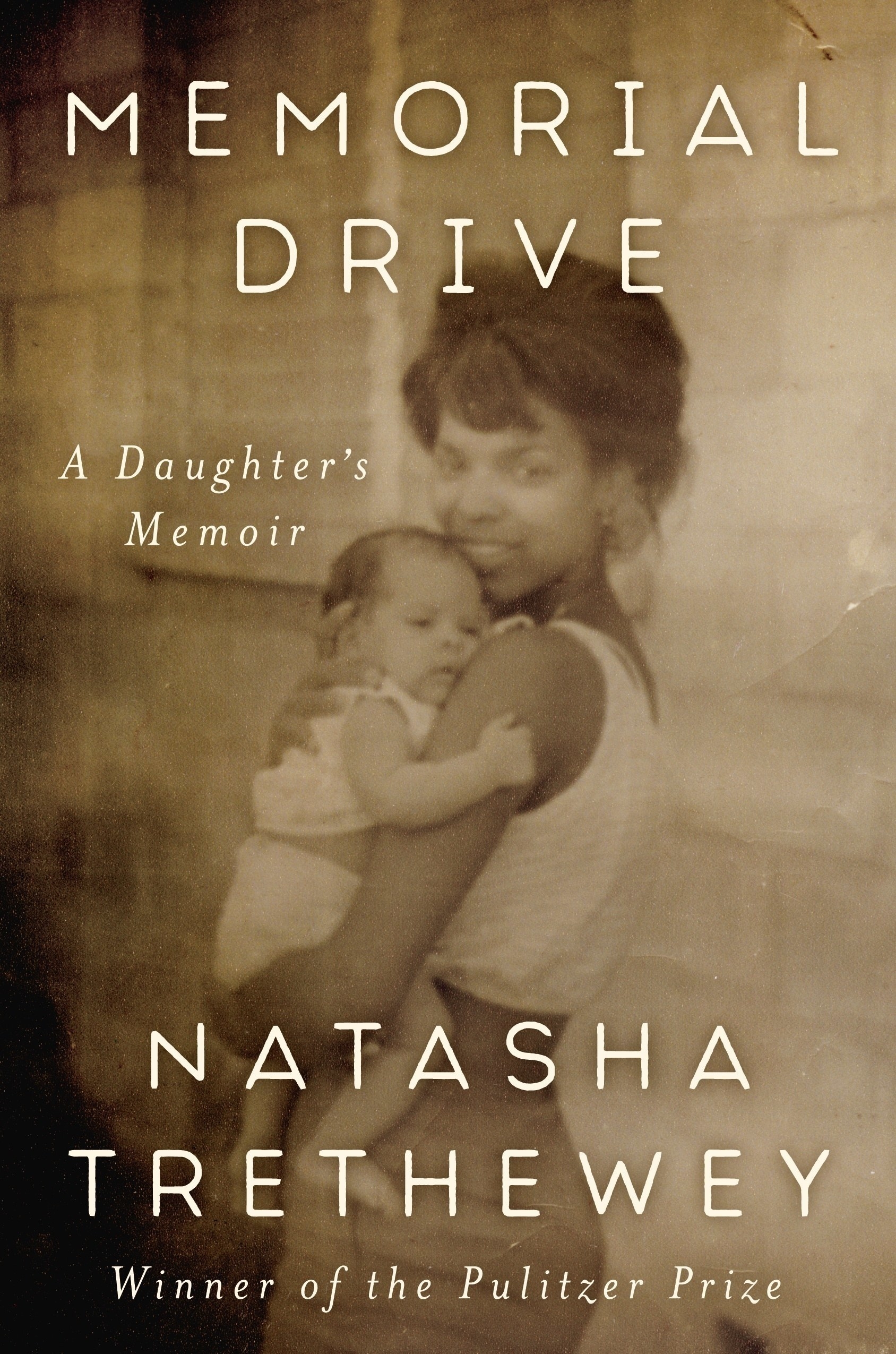

From Memorial Drive by Natasha Trethewey. Copyright 2020 Natasha Trethewey. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Natasha Trethewey is a former US poet laureate and the author of five collections of poetry, as well as a book of creative nonfiction. She is currently the Board of Trustees Professor of English at Northwestern University. In 2007 she won the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry for her collection Native Guard.