CEDAR RAPIDS, Iowa — There’s just one thing holding Bernie Michaels back from voting for Elizabeth Warren.

“It’s long past due that a woman becomes president,” Michaels, who lives in Hiawatha, Iowa, said. “If Warren didn’t have that single-payer thing on her, I would be behind her. I would probably choose her. But I just don’t see that being electable.”

Michaels is retired now, but when he was a member of the Carpenters Local union, his insurance helped him navigate a major health crisis with just a few hundred dollars in copays — insurance he and his union fought for, he said. “People don’t want to give that up.”

As the popularity of Medicare for All has fallen in poll after poll over the last year, a fear is growing among some Democratic primary voters that simply backing single-payer health care would make it too difficult for a candidate to win in a general election.

Jeff Cook, an attorney in Davenport, said he liked Warren, but was considering voting for Sen. Amy Klobuchar, a political moderate. The reason: “Well, it’s that uneasiness about Medicare for All. I like Medicare for All, but I think it’ll be a hard sell to independents and liberal Republicans who might vote for a Democrat.”

If the singular issue of Medicare for All becomes increasingly linked with electability — the factor that remains many Democrats’ top priority in the primary — it could spell trouble for Warren, who has already struggled with questions about whether she can beat President Donald Trump. Bernie Sanders, too, has hinged his candidacy on Medicare for All, but has faced less scrutiny — in part because he has run a campaign less focused on broad appeal to moderate voters than Warren has.

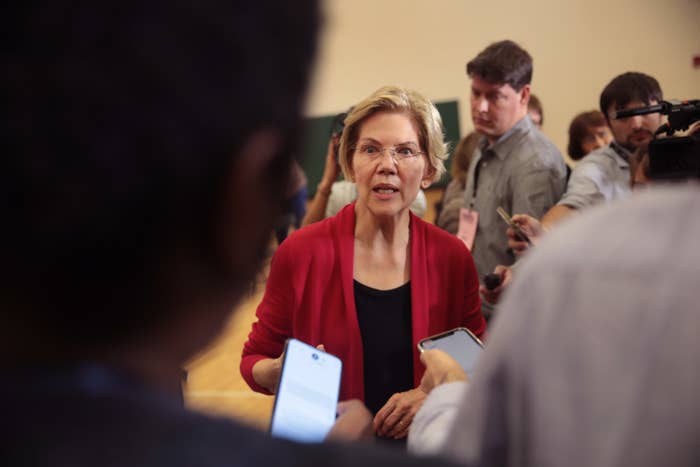

Warren has tried to deal with rising anxieties from voters over Medicare for All, and her own support of it. She traveled around Iowa last weekend days after announcing a plan to pay for a $20.5 trillion single-payer system that would not require raising taxes on middle class families.

Some voters said they were relieved to hear Warren articulate a plan to pay for health care without tax increases that would target them. But there are signs that concerns remain beyond costs — voters who worry over everything from the plan’s political viability to its echoes of socialism. In a question-and-answer session with Warren at a town hall, a voter in Vinton who said she had Type 1 diabetes told Warren she was worried about getting continuity of care in the transition period as Medicare for All took full effect.

“You know, you can’t just change over,” said Bill Wilson, a retired United Auto Workers member who saw Warren in Davenport but said he was leaning towards moderates like former Rep. John Delaney because of their more conservative approach to health care. “I’m a union guy, I’ve got my health care.”

So far in the primary, the question of what makes a candidate “electable” has varied wildly from one voter to the next. Some say it means finding someone who could drive up turnout in cities and Democratic strongholds, while others are looking to someone whose policies appeal to moderate swing voters or a candidate that they think can go toe-to-toe with Trump on the debate stage.

That’s still true. But polls and interviews with voters in Iowa show signs of a worrying trend for Democrats backing single-payer health care: voters who fear that Medicare for All will make candidates less electable against Trump, and, perhaps most importantly, rival Democratic campaigns looking to fuel that belief.

The voters who will matter the most in the general election are decidedly negative on Medicare for All. A poll this week of undecided “swing” voters in Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Pennsylvania — states once known as the “blue wall” that tipped hard to Trump in 2016 — found that a large majority of voters think the single-payer health care plan is a “bad idea.” Just 36% of swing voters said Medicare for all was a “good idea.”

And early-state voters are noticing. A poll in the Des Moines Register from September found that 52% of likely caucus-goers in Iowa thought Democratic candidates shouldn’t run on Medicare for All. Twenty-four percent said outright that they thought it was bad policy, but another 28% liked the policy themselves — but opposed it because they feared it could cost Democrats the general election.

More Iowa Democrats feared Medicare for All could cost the party the election than other progressive issues in the poll, like the Green New Deal, an assault weapons ban, and free public college.

No one sees more of an opportunity in turning voters against Medicare for All than Mayor Pete Buttigieg, who has surged in Iowa — claiming the February caucuses are a two-way race between himself and Warren.

Buttigieg has been criticizing the plan almost relentlessly in recent months. He cut an ad in October that warned “Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren believe we have to force ourselves into Medicare for All, where private insurance is abolished.” Union members, the ad claimed, see Medicare for All “as a loss of a benefit that they fought hard to obtain.”

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi also took the step of publicly urging caution on Medicare for All, suggesting in part that it could be too politically risky. “I’m not a big fan of Medicare for All,” Pelosi said in an interview with Bloomberg Television last week.

“Hopefully as we emerge into the election year, the mantra will be more health care for all Americans,” she said. “Because there is a comfort level that some people have with their current private insurance that they have, and if that is to be phased out, let’s talk about it. But let’s not just have one bill that would do that.”

The idea of “Medicare for All,” popularized by Sanders in his 2016 presidential race, has been touted by progressives as broadly popular: polls in 2017 and 2018 showed most Americans, even independents, supported the policy. But that support has been declining in the face of attacks from Republicans and some Democrats, according to the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation — to just 51% of voters nationally who back the plan, from a high of 59% in March of 2018.

That decline in popularity has put Democrats who backed Medicare for All in a difficult position. Some who co-sponsored the bill at the height of its popularity, like Sens. Cory Booker and Kamala Harris, have backed off the plan; Harris introduced her own version that attempted to assuage voter fears about the elimination of private health insurance and the dangers of an abrupt transition onto a government-run plan.

Sen. Sherrod Brown, an Ohio Democrat who decided not to run for president earlier this year and does not favor Medicare for All, told BuzzFeed News this week that he thinks the Democrats who support Medicare for All now will be able to find a way to ease away from that support come the general election. “I think that what they’re saying now evolves, just like things do,” he said.

It’s Warren, more than any other candidate, who is caught at the center of this issue: pressured to align herself with Sanders, whose supporters she will need to win the nomination, but also wary of voter concerns about the plan’s costs and logistics.

The anxiety from voters is apparent at many of Warren’s events across early voting states. At a town hall in New Hampshire in September, a retired doctor questioned how she would pay for her plan; minutes later, another voter worried about increased costs if she lost her husband’s union-negotiated health plan.

Over the summer, some speculated Warren was seemingly backing away from Medicare for All. Instead, she fully embraced it on the debate stage in June, declaring “I’m with Bernie on Medicare for All.” But unlike Sanders, she would not say that the plan would come with a tax increase for most people, leading to months of criticism over her opaqueness.

“I was so concerned about the lack of a plan for how to pay for Medicare for All, and I’ll say, I’m thrilled that a plan has been developed that indicates that it’s feasible,” Jim, a Warren supporter who lives in Manchester, said in Iowa last weekend.

But while Warren has wiggle room to come up with her own payment plan that does not raise middle-class taxes, by vowing to stick with Sanders she is more tightly bound when it comes to other voter worries — like the fear of losing employer health care plans, something Buttigieg has seized on in his criticisms, saying a single player plan would “take away people's choice.”

Warren has started reframing that line of criticism — arguing that it is for-profit health care companies that take away peoples’ choice, limiting the doctors they can go to and the treatments they can afford. Medicare for All, she told voters in Iowa, is the plan that allows choice.

Her campaign, in response to BuzzFeed News for this story, pitched the plan as bringing $11 trillion in savings to families by eliminating the out-of-pocket payments under the current health care system, a cost instead picked up by the ultra-wealthy and corporations.

On the campaign trail in Iowa last weekend, Warren closed her town halls with her own explicit argument about electability, one that seemed to point directly at Buttigieg and other moderates. It was a line she had first used in October’s debates, under fire from rivals about her health care plan.

“I’m not running some consultant-driven campaign with some vague ideas that are designed not to offend anyone,” she told voters. “If the most we can promise is business as usual after Donald Trump, then we will lose.”