When the 10th grader pulled out his cell phone in class — and refused to put it away — he knew he was breaking the strict rules at Camelot Academy of Escambia, the school he’d attended for the past two years. But he wasn’t expecting the punishment that followed.

An administrator charged with enforcing discipline at Camelot Academy, Jamal Tillery, struck him across the face and dragged him into an empty classroom, hitting him until he fell to the floor, according to a police report. Then, the student told police, Tillery hit him with a trash can.

The injuries were serious enough that when the student, who was 18 at the time, got home from school, his mother called the police and took him to the hospital.

The incident in Escambia, in 2011, wasn’t the first time Tillery had been accused of hurting a student. Six years earlier, when he was teaching at another school, he’d pled guilty to charges related to the assault of a 10-year-old. There, according to a police affidavit, things followed a similar pattern: Tillery dragged a disobedient boy into another room, threw him against a door, and began to hit him with his own shoes, shouting as a witness looked on about how he would not be disrespected. Afterward, the report said, the boy's face was marked with red, his fingers bruised from where he had tried to block the blows. Tillery had pled guilty to disorderly conduct and harassment.

This time around, Tillery was arrested and charged with battery. He took a pretrial diversion that allowed his record to be wiped clean. Tillery maintains he was protecting himself: the student, a troubled kid with a record, struck him first, he said, and he never used a trash can.

School administrators say they are confident Tillery did nothing wrong and was defending himself from a violent student. With Tillery’s record clean, Camelot Academy brought him back on board. The school had no idea that Tillery had a history of hurting a child — the 2005 incident with the 10-year-old, they said, had not come up in an FBI background check. That same year, as Camelot Academy’s director of operations, Tillery was accused of hurting two more students in physical altercations, police records show — one of them a 13-year-old boy. No charges were filed in either case.

Inside all of Camelot’s publicly funded schools, security, order, and behavior modification take precedence over academics.

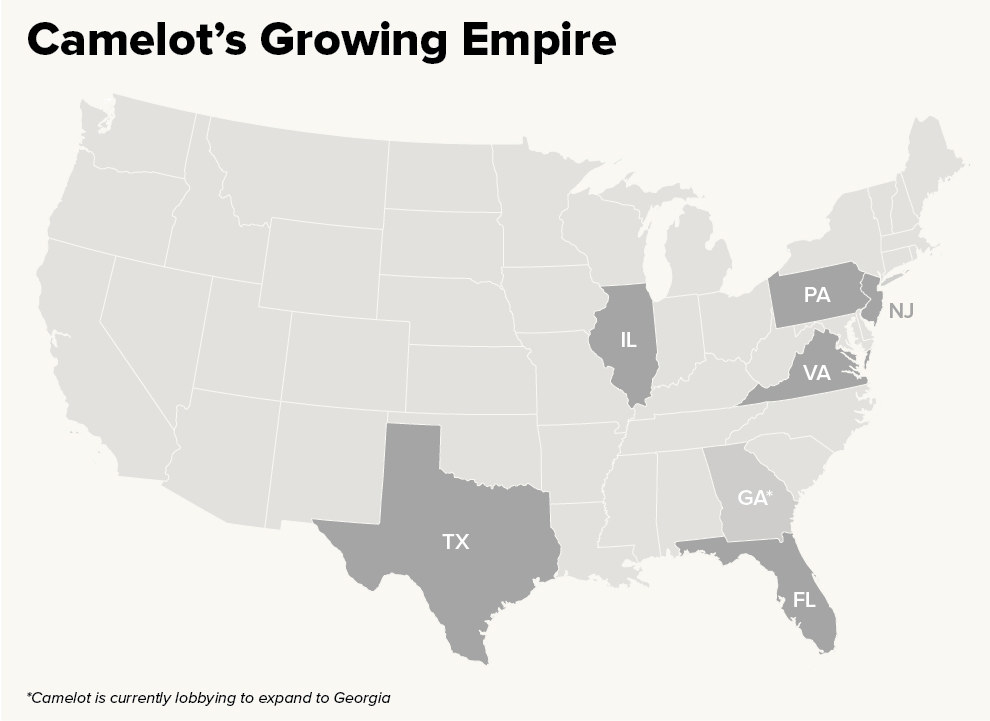

Camelot Academy of Escambia isn’t a public school, though it is funded by taxpayer dollars. It is part of a fast-growing for-profit company, owned by private equity investors in California, that school districts hire to handle their most difficult students: kids with behavioral problems, those struggling to keep up, and those at risk of dropping out of the school system entirely.

Camelot Education now owns 43 schools nationwide, making it one of the country’s largest alternative education providers. It has made a growing business out of taking in troubled kids at sharp discounts compared to publicly run schools, allowing districts to slash costs — and, at times, to improve their own metrics by shunting off their lowest-performing students. The vast majority of students who come to Camelot are black and Latino.

Got a tip? You can email it to

molly.hensley-clancy@buzzfeed.com, or go to tips.buzzfeed.com to learn how send your tip securely.

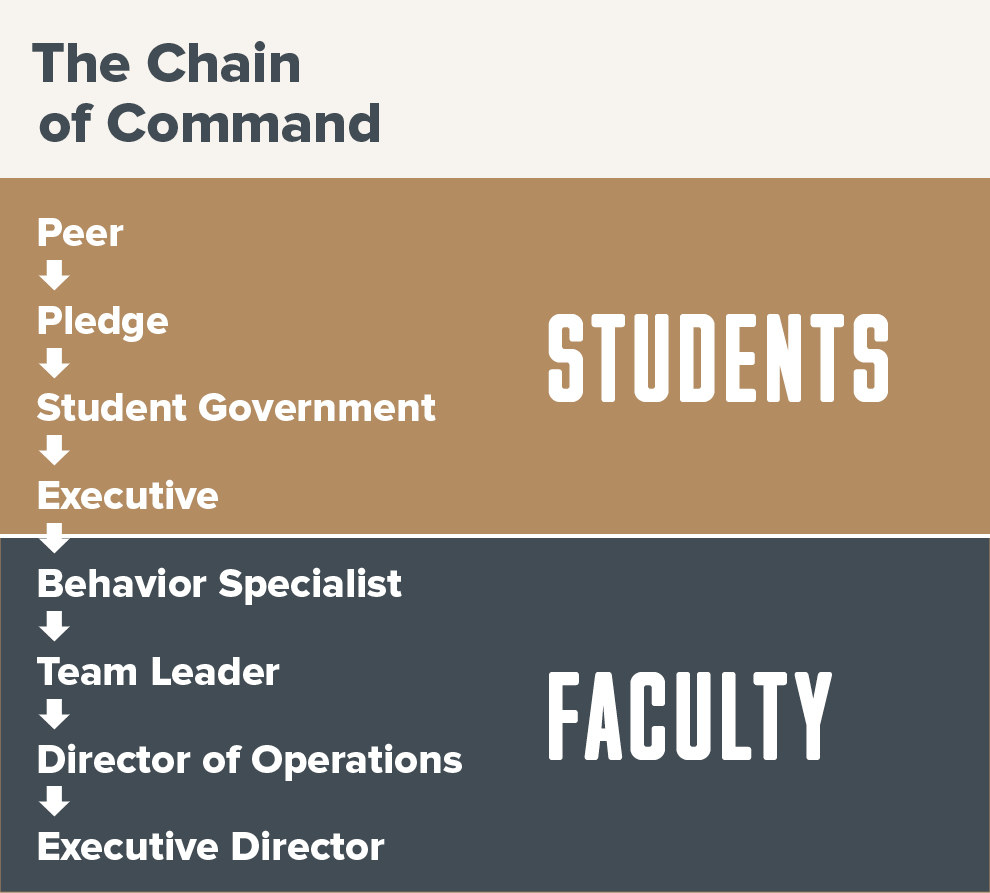

The company has built its business on the “Camelot model,” a rigid system of strict discipline that is based, in part, on juvenile prisons and residential treatment centers. Inside all of Camelot’s publicly funded schools, security, order, and behavior modification take precedence over academics. A rigid hierarchy pervades student life: Top-ranking kids are assigned to an elite club, dressed in special uniforms and given privileges to oversee their peers — correcting their posture, their attire, their behavior. Students are ranked regularly on charts posted throughout the school, where the names of kids who are struggling are highlighted in bright red ink.

“We really subscribe to a sociological model, as compared to a psychiatric model,” said Todd Bock, the company’s CEO. “We believe kids are problems because of the environments they come from. So what we do is behaviorally treat kids — we have to get to their emotional and social issues before we can get to what they’re here for, which is to pull them up academically.”

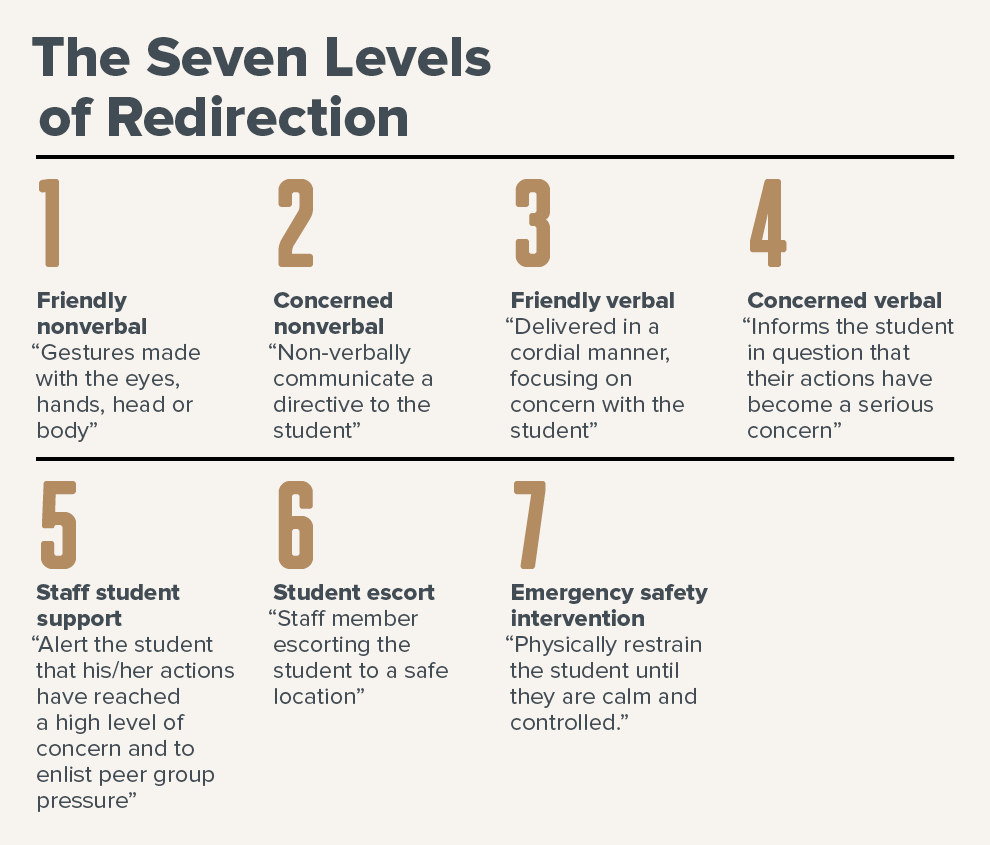

Classes often begin with a recitation: the "Five Norms," which dictate how students behave and treat one another, and the “Seven Levels of Redirection,” a system of escalating responses to misbehavior. The levels begin with a friendly gesture, such as a raised eyebrow, and increase all the way to a Level 7 — “emergency staff intervention" — in which a staff member restrains a student by pinning a student against a wall, arms wrenched behind their backs.

The company says such extreme measures, demonstrated to every new student during orientation, are used rarely — only when kids are in imminent danger of hurting themselves or others.

A string of violent encounters between staff and students have highlighted how the company’s strict, confrontational model can boil over.

But four former teachers told BuzzFeed News that pushing students against walls to restrain them was a regular occurrence at Camelot schools. One said he himself was involved in as many as 10 Level 7 redirections a day at a Camelot school for students with behavioral problems. A string of violent encounters between staff and students — including one, in 2014, that led to two staffers being jailed — have highlighted how the company’s strict, confrontational model can boil over.

There is little to no public data available about how many of Camelot’s students perform on state exams, attendance, or graduation metrics. But the company can claim modest academic gains that set it apart from many other alternative school companies — results that have positioned it to spread even more quickly, as demand rises for school districts to slash costs and boost their metrics.

Camelot executives argue that its model works. Juvenile justice activists, however, say the Camelot system is yet another funnel for the school-to-prison pipeline — an educational model that uses the public school system to treat mostly black and Latino children as criminals before most have ever been convicted of a crime.

The company’s approach to behavior modification,“really seems to mirror everything that doesn’t work in prisons. It’s really troubling,” said Mishi Faruqee, the national field director of the Youth First Initiative, a juvenile justice reform group. “The youth prison model has completely failed — it does not rebuild students.”

Camelot students are reminded just how different their school is from the moment they arrive each morning. Getting through the door requires a full-body pat-down, and students are forbidden from bringing anything — no backpacks, notebooks, textbooks, or pencils — into Camelot facilities, meaning there can essentially be no homework. This level of security is applied to teenagers regardless of whether or not they've ever committed a crime: students who have been expelled from their schools, as well as school dropouts, kids with learning disabilities, girls who became pregnant.

Once inside, students begin each day the same way: with motivation, tough love, and recitation in an all-school assembly called “Townhall.”

One morning in March, students gathered for Townhall in the gym of a Camelot school in Chicago, where a motivational video was projected onto a cinderblock wall. Excel Academy of South Shore is one of five schools Camelot has opened in Chicago, many of them clustered in its most troubled neighborhoods — places so torn by gang violence that shootings on the sidewalks outside of Camelot school buildings are regular features in the local news. Most of Camelot’s Chicago schools recruit students who have fallen behind on their high school credits — “overage and under-credited,” they’re called.

As a speaker onscreen barks about the keys to success, students in white Excel shirts and striped ties look on silently from rows of folding chairs. The newest students sit in the front row, where, staff say, they can be under closer supervision.

Standing over their classmates in Townhall are students inducted into the school’s elite student government because of good behavior and grades. They wear purple and gold sweaters neatly buttoned over their uniforms, hands folded behind their backs. The group is known as the Broncos, named after the school’s mascot; a mile away, in Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood, they’re called the Bulls.

"I'm here to tell you, number one, that most of you say you want to be successful, but you don't want it bad," the speaker on the video rumbles. "You don't want it as bad as you want to party. You don't want it as bad as you want to be cool."

Outside the half-filled gym at Excel, students are still trickling into school, passing through a metal detector before being patted down by a staff member. As a boy pulls off his belt, a female staff member kneels in front of another student, running her hands down the outside of the girl’s legs, and then the inside. She finds a small blue card in the front pocket of the girl’s khakis and examines it, turning it over in her hands.

At some schools, when the pat-down is complete, students trudge forward, remove their shoes, and shake them upside down.

Camelot says the full-body searches are necessary, even in schools that are not meant for students with behavioral problems. “It’s about safety,” said Anthony Haley, one of the company’s executives. “It makes the kids feel safe.”

Faruqee, of the Youth First Initiative, said the pieces of the prison system in Camelot’s model — from the behavioral rankings to the pat-downs and the use of restraint — are “completely ineffective. It’s very harmful to treat students as though they’re living in a vacuum, focusing on the output and just modifying their behavior.”

While Bock’s time working in correctional facilities has molded some of his thinking, he said, it is mistaken to see Camelot as an extension of that system. “If I believed in what juvenile justice stood for, I would still be working in juvenile justice,” he said. “What Camelot does is the real answer for helping kids get out of the system and helping them achieve self-actualization.”

As the daily assembly at Excel South Shore ends, students file out of the gym in hushed groups. First, as always, are the Broncos, who station themselves along the hall like sentries, watching as their classmates walk in small, quiet lines to the day’s first class. Boys step aside to let girls up the stairs first, because, as one of the Five Norms declares, a Camelot student is “always a lady or a gentleman.”

Bought out by a private equity firm called the Riverside Company in 2011, Camelot stands out among companies that have made a business out of educating troubled children. Instead of operating in just one state, as most do, Camelot has spread nationally, running dozens of schools in six states and hiring lobbyists to help it expand into more.

Camelot grows in part because the company can point to results — modest academic gains at some schools and increases in graduation rates — that appeal to school districts in a field where many other companies perform abysmally.

By siphoning off students who are struggling the most — those who are furthest behind academically or least likely to graduate — some districts can use Camelot to pump up graduation rates and test scores at their flagship high schools, allowing them to better attract students and funding, and avoid sanctions from states.

In Florida, school districts have used alternative schools to mask dropout rates, a ProPublica investigation in February found. Struggling students, who were steered into alternative schools and eventually left, were coded as withdrawals taking GED classes rather than as dropouts, the outlet found — giving districts an easy way to appear to meet statewide accountability rules.

If Camelot’s executives get their way, the company, and the Camelot model, could shape the future of alternative education.

Beyond boosting metrics, school districts stand to profit when they work with Camelot, saving thousands of dollars per student each year compared to the costs of running their own programs. Last year, the cash-strapped school district in Millville, New Jersey, cut its alternative education costs in half by privatizing its alternative school with Camelot — saving $600,000 and the jobs of 45 employees. Camelot was dramatically cheaper than the other private company that bid on the contract — $5,000 a year less per student.

At a Millville school board meeting to discuss privatizing the district's schools with Camelot, a board member worried about how the company "can do it for what we’re told is a half or a third of what we’re doing it for and still make a profit for their private equity firm."

But Camelot's program was "better and more cost effective" than anything run by the district, another board member said. Privatization was the new normal, he argued: "The majority of high schools did away with programs like this a while ago and instead send students to a private ... placement."

“What we do is so valuable to taxpayers and our school district partners, because we specialize in that group of kids that have not had success in traditional public school,” said Bock. “I would say 95% or more of our school districts save money by contracting with Camelot.”

What Camelot brings to the table — cutting public spending on education, profit-driven experimentation in alternative kinds of schooling, and the potential to boost test scores and graduation rates — is now in high demand in Washington, DC, where a longtime advocate of education privatization is now the country’s top school official. Under the tenure of Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, who has called the traditional public school system a “dead end” that is ripe for private sector innovation and competition, Camelot appears poised to take off nationally.

For now, the world of alternative education is a hazy space — with a clear demand for privatization but without market leaders or models. If Camelot’s executives get their way, the company could shape the future of alternative education.

Under the guidance of its private equity owners, Camelot has already pulled off an ambitious expansion plan in Chicago, where it is now a dominant player in the city’s burgeoning alternative education system, taking in $50 million in contracts over four years. It is working to open new schools nationwide, including in Georgia, where it has hired two politically connected lobbyists. And it launched a new line of business in Las Vegas late last year, advising the school district there on how to improve its own alternative schools.

Many of Camelot Education’s schools are not schools at all. In Pennsylvania and New Jersey, they are “programs” — meaning they operate by different rules about what classes to offer and how many hours students must complete to qualify for credit.

That makes it difficult, and sometimes impossible, to judge how much learning is actually going on inside Camelot classrooms across the country. There is no publicly available performance data of any kind for the company’s six New Jersey schools, according to the state: no test scores, no attendance records, and no school ratings. The scores of the company’s students are, instead, hidden within the data of the schools they attended before Camelot.

In absolute terms, the numbers that are publicly available for Camelot schools are frequently dismal. Compared to traditional schools, dropout rates are high, and attendance levels low; at Phoenix Academy in Pennsylvania, for example, 1.4% of students are proficient in math, and 11% are proficient in reading. The graduation rate is 66%.

Camelot Academy of Escambia, in Florida, which serves students with disciplinary problems, has a graduation rate of 5.6%, according to the state; just 16% of its students made progress in math, and a little over half in reading. Unlike at traditional Florida schools, Camelot of Escambia isn't graded on a scale of A—F, and there is no way to tell how many of its students reach state standards.

Much of that is by necessity: Experts argue it’s unfair to judge alternative schools, which serve only struggling kids, by the same metrics as traditional schools. At disciplinary schools like Escambia, students flow in and out, often staying for only a few months at a time. But it means that the academic performance of many of Camelot’s programs are, to the public eye, essentially a black hole.

But in Chicago, city data shows that many Camelot schools are steadily improving. Excel Academy of Englewood was given a low “Level 2” ranking in 2014, but now has one of the city’s highest grades. Ninety percent of its eligible students graduated, and its students show significant growth — though, because the state of Illinois considers the schools “programs,” there is no way to know how many students are at grade level.

When Camelot recruits students for most of its Chicago schools, it searches for pupils who have dropped out of school altogether, who are older than 18, or who have fallen too far behind to catch up in regular classes. Teachers and executives knock on doors and man booths at festivals in Chicago neighborhoods marred by poverty and gang violence.

Once students come to Camelot, the school must work to bring them up to speed at a rapid pace, getting them to graduate before they turn 21 and become ineligible for the public school system. It is the central paradox of alternative education: Students who failed in traditional settings are pushed through their credits in half the time or less, zooming through a year’s worth of schoolwork, for example, in a semester.

Camelot gives its teachers an “impossible” task, said Jandy Rivera, a former Camelot teacher: getting children who are years behind academically through their schoolwork in a shorter period of time than students in regular schools.

“I have maybe one or two students at grade level, and the rest are all below,” said Rivera. “How am I supposed to do that at double the pace?”

Rivera, who spent two years at a school in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, is a witness in a lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union against the school district of Lancaster. The district automatically sends older refugee students to a Camelot school, Phoenix Academy, instead of allowing them to attend a traditional school. At Phoenix, the ACLU suit says, students receive 30 fewer class periods of instruction per credit than their counterparts at Lancaster’s traditional high school.

In other alternative schools — many of them also run by for-profit companies — students attend half-day programs, completing much of their work on computers as they click through a sped-up digital curriculum. Teachers supervise their work, but class sizes are large: sometimes as many as 40 students.

At Camelot, class sizes are small and class periods stretch to 90 minutes. Academically as well as socially, the company’s approach is “fundamentally different” to those that run half-day or computer-based programs, Bock said. “We believe our kids need to be in school longer, not shorter, to make up the time they’ve missed.”

A 2010 study by the respected research group Mathematica found that of the alternative schools in Philadelphia, Camelot’s students fared the best, with their graduation rates increasing 12% compared to peers who were not enrolled in the schools. It was the only alternative education provider in the study to have any statistically significant impacts on its students’ outcomes.

Still, even though its students stay in their seats longer than at most other alternative schools, Camelot’s basic model is to move students rapidly through the curriculum, rushing through entire grades in a matter of months.

The ACLU’s lawsuit paints a dismal picture of academics at Phoenix Academy. The refugee children in the ACLU’s lawsuit were sent to Phoenix with “no English skills” — not even enough words to understand why they were being patted down on their first day of school. But they passed Phoenix’s classes with ease, flying rapidly through grade after grade.

One student, Anyemu Dunia, went from 9th grade to 12th grade in the space of a school year. For Dunia, 11th grade lasted from Jan. 19 to May 24, the suit says. By June 2, he had graduated from high school. Another boy, Qasim Hassan, stopped attending Phoenix on March 29, his transcripts show, and had 59 unexcused absences. He was promoted to the next grade.

“Learning? No,” said J.A., who taught at a Camelot accelerated school for two years. While students benefited socially from the intense discipline, she said, any academic progress was limited. “Children that were at a third-grade reading level were supposed to graduate in seven months. We did what we could.”

John Harcourt acquired what would become Camelot Education in 2002, when it was a small health care company. Until 1999, Harcourt had been the CEO of the Brown Schools, which ran a collection of boarding schools and wilderness camps for troubled children. An Austin American-Statesman investigation found that at least five children died at the Brown Schools between 1988 and 2003 after they were improperly placed in restraints — including a 9-year-old boy who, in 2000, “was held to the ground until he vomited and stopped breathing,” the paper wrote.

Harcourt brought other Brown Schools executives along with him to Camelot, including Todd Bock, now the company’s president. Camelot says the two organizations share only a tiny fraction of employees and have “nothing to do with the other.”

Bock, who has a bachelor's degree in criminal justice, previously worked at the Glen Mills Schools, a prison alternative for teenaged boys that combines a prep-school environment with, as the school’s onetime leader described it to the St. Petersburg Times, “a system of social control borrowed directly from street gangs.”

With what they’d learned in years of dealing with troubled children, Bock, Harcourt, and others would build Camelot Education into a new kind of alternative school. And some Camelot hallmarks appear directly inspired by what came before: At Glen Mills, a student government called the Bulls rigidly policed classmates’ behavior, “confronting” other boys lower in the social hierarchy about even minor rule-breaking.

“I didn’t hit him with the shoes,” he told BuzzFeed News. “I was playing with him with his shoes. I was playing. That’s what the ‘disorderly conduct’ charge was.”

It was Glen Mills that helped make Jamal Tillery the man he is today. During his own troubled childhood, he landed at the school, and he says it was exactly what he needed. “You had male role models, you had norms, you had accountability, you had structure, discipline,” Tillery told BuzzFeed News in February. “Most importantly, you had consistency.”

It worked, he says. Tillery made it through college, where he graduated with a degree in criminal justice. His LinkedIn profile says he has master’s degree in alternative education, but the school he says he attended, Lock Haven University of Pennsylvania, told BuzzFeed News that he never graduated.

He touts his life story as a positive, helping him to relate to the troubled youth he has worked with for more than a decade. “I’m keeping these kids from being arrested and going through the criminal justice system,” he said. “I got out, but they might not.”

Camelot calls Tillery an “exemplary” employee. Its CEO says the 2005 incident, involving a 10-year-old boy at school in Pennsylvania, “was nothing more than a summary offense.” Bock cast doubt on the allegations of violence listed on the police affidavit, noting that Tillery pled guilty to lesser charges. “If he had done that to a 10-year-old, do you actually think he wouldn’t be in jail?”

Tillery blames the boy’s injuries on another man whom the affidavit lists as a witness to the beating. “I didn’t hit him with the shoes,” he told BuzzFeed News. “I was playing with him with his shoes. I was playing. That’s what the ‘disorderly conduct’ charge was.”

A history of physical confrontations with students has not slowed Tillery’s ascent through Camelot’s ranks. After the company moved him out of Florida, he became the executive director of one of its newest schools in Chicago.

“I felt like I was working in a prison,” said Rivera, a former teacher. When she had to take a shift patting down students at the school entrance, Rivera said, “I found myself, almost every time, saying, ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry honey.’ I would try to chat as I was patting them down — asking, ‘How was your evening? What did you do yesterday?’ as she turns around and I pat down her legs, as I feel underneath her bra strap.”

The refugee students in the ACLU's lawsuit, too, were subjected to daily searches at Phoenix Academy, the lawsuit says — some of them Muslim girls, many who barely spoke enough English to understand why they were being patted down.

"I would try to chat as I was patting them down — asking, 'How was your evening? What did you do yesterday?' as she turns around and I pat down her legs, as I feel underneath her bra strap."

While Rivera apologized to her students during the pat-downs, she said, some of the male staff — mostly the school’s “behavioral specialists” — would use the pat-downs as “an opportunity to be aggressive” with some of their more troubled boys.

“They’d be rough with them,” Rivera said in an interview with BuzzFeed News. “They’d push them around, pull on their clothes. It was almost like they got off on that, that authority.”

Behavioral specialists, who often have backgrounds in criminal justice as well as education, roam the halls at Camelot schools, acting as a support system for teachers and “redirecting” students when incidents arise. Mike Tyler II, an engineering teacher at Camelot Academy of Southwest, in Chicago, said that specialists helped to de-escalate tense situations with his students. “They’re not just muscle,” Tyler said.

One former behavioral specialist said that though the position had been advertised as a job counseling troubled youth, it quickly became clear that it was something more akin to a “security guard”: performing pat-downs, supervising walks through the halls, talking down and sometimes restraining rowdy students.

In the Camelot system, students are the school’s primary enforcers.

In the student handbook, the first criteria for success — before “working together” and “taking pride” — is confrontation. “HELP TO CORRECT YOUR PEERS,” it commands in all caps. Students who want to be promoted to the next level must “vocally” confront classmates who are breaking school rules, it says; those who reach the highest echelons are “consistently” confrontational, documenting their corrections of classmates on a form called a “pledge log.”

“At the Pledge level, students should be effectively using their time by confronting their peers,” the handbook says. “It is very important that the students understand that school personnel are observing their confrontation style with other students and will look at their Pledge Logs to see who they have been confronting [and] the reason for the confrontation.”

“When kids intervene and confront negative behavior in school, it’s so much more powerful than when an adult does it.”

As Camelot envisions them, confrontations are meant to be supportive: students quietly reminding their classmates to “fix themselves,” as Bock phrased it, and, if necessary, even reminding teachers and other staff to do the same. At Excel Academy of South Shore, a Bronco pulled aside his classmate to fix the boy’s purple-and-yellow striped tie; another student in the club urged a teacher to speed up her conversation so that he could make it to his hallway post on time. “That’s the model working,” the teacher said.

“We have to confront those behaviors, because when they go unchecked, it’s counter to the culture of our school,” said Bock. "There's thousands of interventions a day — some that are as simple as shirt being untucked, and a friendly, nonverbal confrontation, where you make eye contact.

“When kids intervene and confront negative behavior in school, it’s so much more powerful than when an adult does it,” he said.

At Camelot Academy of Englewood, a whiteboard in the executive director’s office listed possible solutions to school’s struggles. To deal with kids not following the Norms, staff brainstormed offering rewards and helping students better understand the rules. At the top of the list: increasing confrontations for minor offenses. “Make an example out of the small stuff,” it read.

At daily Townhalls and before every class period, Excel South Shore students chant the Seven Levels of Redirection, Camelot’s method for dealing with bad behavior. It’s done, Bock said, because “it’s important that kids understand what their rights are and how behavior is going to be addressed. Unfortunately, we have to have systems like [this] because sometimes, not often, students become a threat to themselves and others around them.”

Camelot executives and school leaders say it’s very rare for incidents to reach Level 7, where students are physically restrained. At a small disciplinary school run by Camelot, with just a few dozen students, the principal said they had yet to use the seventh step this year. “It rarely goes beyond the second or third,” he told BuzzFeed News.

One former teacher, who did not want to be named, said she had only seen the seventh step used when students were in danger. Camelot’s behavioral specialists were lifelines, she said — she’s five feet tall, and when her students grew disruptive, she couldn’t have handled them on her own. “Does anyone go into it thinking, ‘I have to do step two, now step three, now step four?’ No,” she said. “You would go right to step six if the student is being very belligerent.”

But at some Camelot schools, staff were frequently physical with students, and at times used the guise of a seventh-level intervention to punish students who had stepped out of line, according to four former staff members, news reports, and the ACLU’s lawsuit.

“They would restrain a kid for absolutely no reason whatsoever — snatch him out of a chair,” Rivera told BuzzFeed News. Of the six men who frequently intervened using the Camelot restraint system, she said, only two used the system the way it was intended, working first to de-escalate the situation verbally. “The rest would take the opportunity to slam a kid against the wall — to escalate something from a step two to a step seven.”

A Louisiana juvenile court judge told the New Orleans Times-Picayune in 2009 that he regularly encountered Camelot students who said they had been “slammed” against walls or seen their classmates subjected to the treatment. Photos showed a hole in the wall where a girl had been rammed for disobedience, the article said.

Rivera said she witnessed a senior staff member pull a troubled student behind closed doors after he had been acting up. The boy emerged with a black eye, puffy lip, and bruised neck, she said. The staff member attributed the injuries to a fall.

After they saw their classmate’s injuries, Rivera said, the other students were stunned. “A kid asks me, point-blank, ‘What are we supposed to do if they do something to us at school that they’re not supposed to do?’”

Bock said that Rivera had little credibility because she had failed to report any of the incidents at the time. “If she had witnessed anything that even looked remotely like a kid was being mistreated, she’s a mandatory reporter under the law,” he said. “It wasn’t reported because it didn’t happen.”

"It’s hard not to feel resentment for the company — I do think they’re operating with the best intentions for students, but at the same time, they’re for-profit. That leads to schools that are understaffed and underfunded."

Three other teachers at Camelot’s accelerated schools, who asked that their names not be used, told BuzzFeed News that restraint was used regularly. “Everything is professional,” one teacher said, adding she had never seen restraint used to punish a student, only to prevent them from harming themselves or others. But, she said, “There’s just a lot of it going on. It would happen every day.”

Bock disputes this. “It’s the very last option we have, and it doesn’t happen often,” he said. The company said it tracked how frequently restraints were used in schools, but it would not provide the data to BuzzFeed News. “I can say with 100% confidence that it doesn’t happen every day — and nowhere close to every day.”

One former Camelot teacher of more than three years, who did not want to be named, said that while working at a Camelot therapeutic school for students with behavioral disorders, he had personally participated in three to ten restraints a day.

That happened at a time, the teacher said, when the therapeutic school had too few support staff, most of them underpaid and inexperienced. That led to a handful of restraints that, he said, “made me uncomfortable.” The teacher said he witnessed a similar problem at other schools they visited: restraints that — while they did not physically injure children — “actually escalated the situation.”

The teacher’s complaint of underpaid staff reflects one of the major strengths of Camelot’s business model. The company spends far less on salaries than comparable district run schools, and “we don’t have collective bargaining agreements with our employees — so we get a lot more flexibility with our staff,” Bock said.

Without unionized teachers — and with different requirements for teacher certification than district schools in some states — Camelot can pay dramatically less — especially when it comes to behavioral support workers. But as a result, three former teachers said, teachers are often inexperienced, and behavioral staff even more so.

For the teacher at the Camelot therapeutic school, that lack of experience had serious consequences. “I was really getting burnt out,” he said. “I was injured, my colleague was injured. It’s hard not to feel resentment for the company — I do think they’re operating with the best intentions for students, but at the same time, they’re for-profit. That leads to schools that are understaffed and underfunded.”

On the walls at South Shore, in classrooms, displays, and even hallway corners, are the school’s behavioral rankings — color-coded charts that sort students into categories based on how well they’ve behaved. Black denotes students in the elite student government; green students are working on being inducted into the club, collecting logs of their “confrontations with others.” Students begin on neutral yellow, and, with repeated problems, are downgraded to red — a level that, Camelot materials say, has no privileges whatsoever.

At South Shore and several other Excel schools, as many as half of the students on the chart have been given a red ranking. But none of the students whom Camelot asked to speak with BuzzFeed News had ever been on red. All but one were members of their school’s elite student government.

Some parts of Camelot schools look familiar. Mike Tyler II, the teacher at Camelot Academy of Southwest, spoke eagerly about a robotics team he started with the company’s help. In the hallways of South Shore, students point out assignments they’ve done and posters from school-wide events — poetry contests, essays on their neighborhoods, a black history trivia contest that brought together students from all of Camelot’s Chicago campuses. On a chart that tracks their progress in senior year — whether they’ve taken the SATs or filled out financial aid forms — some have ticked off all the boxes. Other students’ charts remain blank.

At another Camelot campus in Chicago, which houses students who have been kicked out of their previous schools, two middle school boys say they’ve chosen to stay at Camelot rather than return to traditional schools, even though their suspensions are up and the bus ride to school can stretch almost 45 minutes. “I’m doing good here,” said one shy boy who landed at Camelot after bringing a gun to his Chicago middle school. “That’s why I want to stay.” He had been dressed in the costume of a knight, the school’s mascot, in preparation for a visit by BuzzFeed News.

Other members of the student elite seem to have thrived at Camelot. One told BuzzFeed News he wants to go into the air force, and another said she wants to be a midwife. “The model works perfectly,” said one girl as her principal and a Camelot executive looked on. ●

Got a tip? You can emailmolly.hensley-clancy@buzzfeed.com, or go to tips.buzzfeed.com to learn how send your tip securely.

Outside Your Bubble is a BuzzFeed News effort to bring you a diversity of thought and opinion from around the internet. If you don’t see your viewpoint represented, contact the curator at bubble@buzzfeed.com. Click here for more on Outside Your Bubble.