MINNEAPOLIS — The young woman answered Jared Mollenkof’s question with what sounded like a question.

Standing in her wool socks on the stoop of her home in Northeast Minneapolis, she looked anything but certain about the question of whom she planned to vote for on Tuesday.

“I do really like Elizabeth Warren too,” she offered, looking at the faded stickers on Mollenkof’s winter jacket: Warren for President, Warren Has a Plan for That. “She’s right behind.”

Mollenkof explained why he was voting for Warren, a spiel he’s given hundreds of times by now at doors across Minnesota, which will go to the polls in the Democratic primary on Super Tuesday. With her arms crossed tightly, the woman told Mollenkof she agreed with everything he said: She loved Warren, thought she was amazing. But.

“I just do worry about her beating Trump,” she said. Her voice went up in a question again. “Sort of…with regards to her as a woman? That’s why I’m leaning towards Sanders.”

The woman listened, nodding eagerly, as Mollenkof, who is black, explained that he worried too — all the time. He wanted to beat Trump more than anything else. He assured her the data, the history, didn’t back up the fear that a woman couldn’t beat Trump. He told her why he thought Warren could.

“I guess…I guess I should just figure out whether I’m for Bernie or Warren,” the woman said. “I do think that maybe my fears are irrational too.”

But as Mollenkof trudged through the crusted-over snow to the next house, and the next, he said he didn’t have much hope that the woman would change her mind. More than likely, he thought, she would end up voting for Bernie Sanders.

By his count, Mollenkof had knocked on 1,250 doors for Warren, across not just Minnesota but Tennessee, his home state, and on freezing cold weekends in Iowa, too. He had heard that same worry, that Warren couldn’t win because she was a woman, a lot. And he had tried to talk people out of it a lot.

And the more he’d heard it, the more Mollenkof saw Warren slide in the polls.

With three days to go until Super Tuesday, he was upbeat. He was hopeful. And he was also getting, well, a little angry.

“I think we could unite after a contested convention,” he said. “And I kind of want to leave some blood and teeth on the way.”

“Blood and teeth” — a phrase borrowed from Warren a decade ago, in her fight to create the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Her first choice, she had said, was to create a strong, independent agency. “My second choice is no agency at all and plenty of blood and teeth left on the floor.”

Warren hasn’t won a single delegate since Iowa. But she raised $30 million in February. And in the wake of an abysmal finish in South Carolina on Saturday, her campaign began to talk openly about a contested convention — their plan to take the fight all the way to Milwaukee, where the convention will be held, in July.

She has stayed in the race even as two other candidates, Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar, dropped out in the days before Super Tuesday, endorsing Joe Biden in an attempt to consolidate the moderate wing of the Democratic Party.

Warren has given no indication she will do the same. On the campaign trail lately, she has been fighting, openly, with the fierce energy that began her career in politics.

To understand why, you can look at Jared Mollenkof.

“Every office I’ve ever worked in has told me they want to have more black employees, but it’s just a supply, not a demand, issue,” Mollenkof said. “I am just so fucking sick of people saying, like, ‘I really want a woman to be president, but just not this woman at this moment.’

“And I want the party to have a reckoning with that fact.”

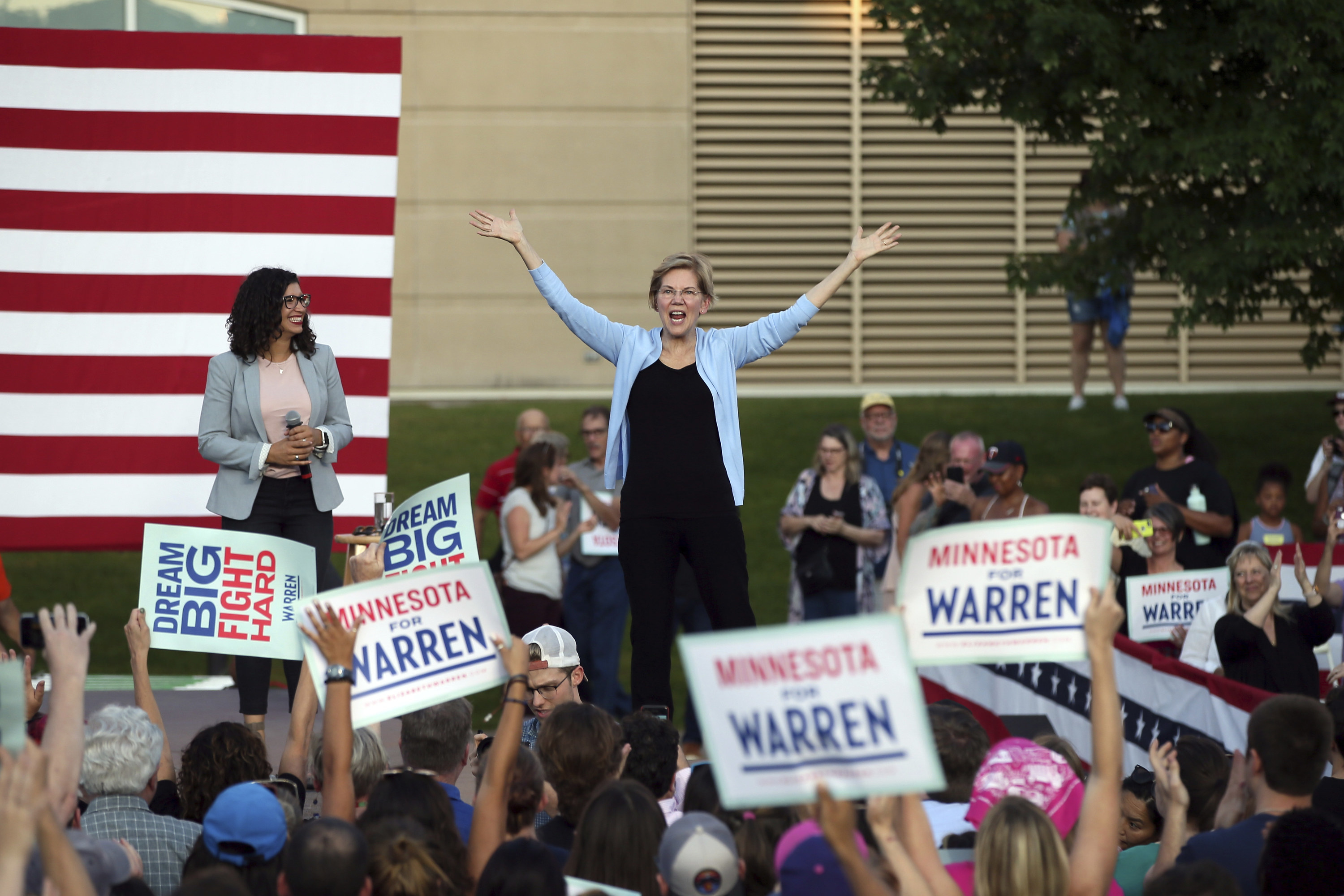

Minnesota was ground zero of Warren’s steady rise last summer: In August in St. Paul, in the midst of a drumbeat of excitement over her plans and unyielding anti-corruption message, she drew the largest crowd of her campaign at that point in the race — some 12,000 people out on the grass in the late summer sun. She stayed for more than two hours to take selfies.

That all feels far away now, with the ground packed hard with snow.

There aren’t clear, obvious answers about what happened between then and now, with Warren’s shot at winning a majority of delegates almost entirely gone.

Pundits have blamed Warren’s fall on her wavering stance on Medicare for All late last summer, her unwillingness to change her messaging into the winter, her lack of momentum, her rejection of traditional methods like super PACs.

But Warren also built her campaign on the back of a massive army of paid organizers and volunteer canvassers and phone-bankers. She didn’t spend her money on pollsters to tell her how to fine-tune her message or television ads to blanket the airwaves in early states. Her campaign thought it was better off persuading voters in one-on-one conversations.

That army was thought to be one of Warren’s strengths going into Iowa. As she has struggled in those early states, many observers have wondered if it wasn’t also a weakness — an overreliance on grassroots organizing that seems, in the end, not to have mattered as much as they’d hoped.

But Mollenkof and other organizers he works with in that grassroots army have seen enough, talked to enough people, that they have come up with their own idea of what happened. In the end, it’s pretty simple, they think: It’s misogyny.

Neil Chudgar was one of the first volunteers for Warren’s campaign, long before she had paid staffers in Minnesota. He spoke wistfully of last summer, when Warren was at her height: “It really looked like we were going to win the state.”

There was the huge, energetic crowd in St. Paul. And, especially, the Minnesota State Fair — Chudgar remembered that in the famous “bean ballot,” where fairgoers place dried beans into clear tubes to cast their primary vote, Warren was the only candidate in state history to need a whole extra tube to hold her beans. She won 38% of the vote, doubling even Klobuchar.

What does he feel now, with Warren far behind in state polls?

“I love Elizabeth Warren,” Chudgar said simply. “And I’ve learned more about misogyny in the past few months than I ever realized.”

There was one day, specifically, when Mollenkof started to think about how he wanted to leave behind “blood and teeth”: the debate in Iowa, when Warren was asked about news stories that Sanders had told her he thought a woman could not beat Trump.

“I think it's really shitty that the fight with Bernie turned out better for him than for her after it seems pretty clear that he said that shit," Mollenkof said. “And the fact that people don't think she's smart enough to know that accusing a man of sexism would result in her losing votes is offensive. She was aware of how that was going to play out, and she did it anyway because that was the truth — and she lost votes in New Hampshire.”

Mollenkof, who works as a public defender, fell in love with Warren early in the race, and followed her through her ups and downs — a “roller coaster,” he called it.

He had originally expected to spend Monday and Tuesday focused on the trial of a client; he had worked some 140 hours over the past two weeks preparing for it. But at the last minute, the state dropped its case.

That meant more time to canvass for Warren. After doorknocking from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Saturday, he would be out the next day, and the next.

To celebrate, Mollenkof painted his nails with a thick coat of liberty green, the color of Warren’s campaign, smudging the paint around his cuticles. He hadn’t wanted to have his nails painted in case of a trial: You never know what a juror might think.

He is still fiercely, tirelessly, behind Warren. But, he admitted, canvassing for Warren was “a lot easier” back that summer — not because of his own feelings about the candidate, but because people were eager to talk about her. They liked to be part of the winning team.

“I was ready to gamble a lot of money on her being president,” Mollenkof said.

Lately, instead of gambling, he has simply been donating a lot of money to Warren — more than he’s ever given to another candidate, despite his love for Barack Obama and his work on behalf of Hillary Clinton in 2016.

Like Warren’s team, he’s convinced she’s the only candidate who can unite the Democratic Party’s ideological wings. There’s another thing driving him too.

"It feels like you’re watching a game play out that's rigged against one team,” Mollenkof said.

“The basketball hoops have been set at different heights, and you're watching, and the refs aren't doing anything about it. And you just get angrier and angrier.”

After the devastation of Clinton’s loss in 2016, Mollenkof did his research as he tried to decide who to back in the 2020 primary. He bought books by Sanders and Buttigieg. He wanted to be excited about Buttigieg, he said: Mollenkof is gay, and there was something meaningful about that. And he did like Sanders’ politics; he’d voted for him in the 2016 primary.

But Warren was the one Mollenkof fell in love with. He loved the way she talked about poverty and race and class. He loved the way she listened. She was the candidate, he thought, who could truly run the federal government competently.

Mollenkof has only met Warren briefly — a few unremarkable conversations in selfie lines. But like so many of her volunteers, he feels like he knows her personally. He tells voters not just about her plans, but how she created them. He tells them about how nice she is to her staff. Watching her this election, he said, felt like cheering your kid as they run a big race, one you know they might not win. You’re just that invested.

Mollenkof’s love for Warren, he said, came in large part from talking to people of color who respected her: DACA recipients, black women criminal justice advocates in the South. “Those women do not pity a fool, and that sealed it,” he said.

Mollenkof has watched, though, as Warren has struggled with black and Latino voters. The support he thought she might get at first never materialized. That night in South Carolina, she would finish with around 5% of the black vote.

He isn’t entirely sure what happened.

“It— I have wondered if there is some level on which that, like, people just reached the conclusion that a Harvard professor that grew up in the places that she did would be incapable of really relating to African American communities,” Mollenkof said. He thought her claim of Native American ancestry might have had something to do with it too.

“It makes me nervous to try to put my finger on why — why the coalition hasn’t been more diverse. Especially when it seems like some of the endorsements would have been so helpful, and I…I don’t know.”

Of the hundreds of doors Mollenkof has knocked for Warren, the one that sticks out to him most was one of the first people he met in Minnesota, in the mostly black neighborhood of north Minneapolis. An older black man invited him into his home, he said, and proudly showed off a display on his wall: a full-size stop sign that he’d written “TRUMP” on the bottom of, decorating it with Christmas lights. The man was retired and lived alone; it wasn’t clear whom the sign was really for, besides himself.

To Mollenkof, the man is a reminder.

“I don’t know how the Democratic Party does the best job of honoring the experience of the people that have been most harmed by the Trump administration,” he said. “But it is important that when we get him out of office that we don’t just try to turn the page and try to cross the aisle, but we actually hold people accountable for the crimes this administration has committed.”

Mollenkof believes there are only two candidates who “have the stomach” to do that: Warren and Sanders.

Did he think the man from north Minneapolis would vote for Warren?

“I don’t know,” Mollenkof said. “I don’t know who he’ll vote for.”

“Hey hey,” Mollenkof said over and over again when voters opened the door. “I’m a volunteer with the Elizabeth Warren campaign.”

He always makes a point to say he’s a volunteer; white voters, of which there are very, very many in Minneapolis, always assume black volunteers must be staffers, Mollenkof said. “They think you must be paid to do this,” he explained. People are ruder when they think you’re getting paid.

All day Saturday, from voter to voter, up one block of modest single-family homes and down another, the sense of anxiety was strong. There were a lot of undecided voters, a lot of people who admitted they didn’t care about issues as much as they wanted to beat Trump. Despite a highly engaged, almost entirely Democratic electorate in Minneapolis, Mollenkof passed few yard signs: one Amy, one Bernie, one that said “Any Functioning Adult.”

“She’s taken a knock,” one Warren voter told Mollenkof, sadly, squinting out into the sun from her porch. “I don’t really know what to do about it.”

“I think a lot of people have gotten worried about pundits and polling,” Mollenkof told another woman. “But if people get out and vote their heart, then we’ll end up in the right place.”

Mollenkof gets the anxiety, he said. He feels it too. But he doesn’t listen to it.

"I've been an eternal optimist on every campaign I've ever worked on,” Mollenkof said. “I've doorknocked on Election Day thinking we’re going to win on every campaign I've ever worked on.

“It'll be so much less fun if I don't fully engage and drink the Kool-Aid in that regard, and so I do.”

A lot of the campaigns he has worked on have lost. There was Hillary, of course. But one loss that really sticks out to Mollenkof was from the 2018 midterm elections, when he was living in Tennessee. He campaigned hard for Phil Bredesen, the former governor, who was running for Senate.

Mollenkof really thought Bredesen could win, he said. But he can pinpoint the day he believes Bredesen lost the race: when he said he would have voted to confirm Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court.

It was a bid to win some of the state’s moderate and conservative voters. But that was the day when so many of the young, progressive women who had been working tirelessly on Bredesen’s behalf simply stopped showing up to phone-bank and canvass. Bredesen said it on a Tuesday; by that weekend, Mollenkof said, 60% of their volunteers had canceled on them.

He couldn’t blame them. He was “pissed,” too. And even though he still showed up to canvass, he did less than he would have. He felt he couldn’t push family and friends to volunteer, either, because they asked a question he didn’t really have an answer to: “If he was going to have voted for Kavanaugh, why do I care if he’s in the Senate?”

This is the theory that drives Mollenkof, and a case he makes over and over again as he campaigns for Warren. The candidate who will beat Trump, he said, is the one who can inspire the widest swath of people to turn out to the polls, not the one who will just flip voters away from Trump.

We don’t need to change Republicans’ minds, he told a young couple on Saturday who had invited him out of the cold and into their home to talk about electability, despite the fact that they had friends visiting from out of town.

“It’s the people who don’t even show up to vote,” Mollenkof told them. “The 144,000 people in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania who didn’t turn out in 2016.”

Mollenkof grew up in a religious, anti-abortion home, the son of evangelical missionaries in Africa. His father, who is white, is extremely conservative but deeply opposed to Trump; he dislikes the president so much, Mollenkof said, that he changed his stance on issues like climate change to be as far from Trump’s as possible. But he didn’t like Hillary Clinton, either. Mollenkof thinks he probably didn’t vote in 2016.

Does Mollenkof ever think about picking a Democratic nominee whom his father would vote for too?

“No,” he said simply. “Because I wouldn’t want to vote for that person.” ●