NASHUA, New Hampshire — When a group of voters leaving an event for Sen. Elizabeth Warren piled into an elevator, buttoning up coats and putting on gloves, the conversation immediately turned to a familiar topic.

“They’re all good — all of the Democrats,” one woman said. “The question is, who’s going to be able to go up against Trump? Take all his bullshit and throw it back to at him.”

“Honestly,” a stranger agreed. “That’s all I care about.”

“They have to be as ruthless as he is,” a third woman said.

But the first woman disagreed. “Not even ruthless — just smart. That’s all I want.”

They laughed. As the elevator door opened, one added: “Let’s just beat the bastard.”

In past presidential elections, Democrats sought out candidates who shared their values and priorities. But this time, in the shadow of President Donald Trump, polls show many Democratic voters are prioritizing one thing: electability.

In some circles, the word “electable” has become a proxy for moderate — a political centrist whose policies appeal to swing voters in states Trump won in 2016. Sen. Amy Klobuchar has electability, some say, because she won reelection by broad margins in Minnesota, a state where Trump barely lost in 2016. Allies of Joe Biden, with his history of bipartisanship and working-class centrism, claim electability is his strongest case for the Democratic nomination.

Who might not have it? Mostly candidates in the most progressive wing of the party: Elizabeth Warren might have an “electability problem.” So, some have worried, might Bernie Sanders.

But the vast majority of Democratic voters aren’t thinking about electability in terms of ideology, geography, or electoral margin, according to interviews with more than 50 Democratic voters in early primary states.

Far from tying electability to centrism or moderation, voters said they cared about rhetoric, personality, energy, and momentum when deciding if a candidate could win. Many others said they were looking primarily for someone who spoke specifically to the concerns of working-class people. Some wanted a fighter who could parry Trump’s rhetoric. Just two said they were looking for a political moderate.

Their answers illustrate a conundrum for Democratic candidates in 2020. What is seemingly a broad voter consensus — that Democratic voters are searching for electability — is, in reality, a much more varied desire.

What voters are actually saying also undercuts a narrative about the choices Democrats will make in the 2020 primaries. While polls have forced Democrats to reckon with choices between candidates who agree with them on issues and those who might beat Trump, voters overwhelmingly said they saw little conflict between the issues they cared about, like Medicare for All and income inequality, and a candidate’s electability.

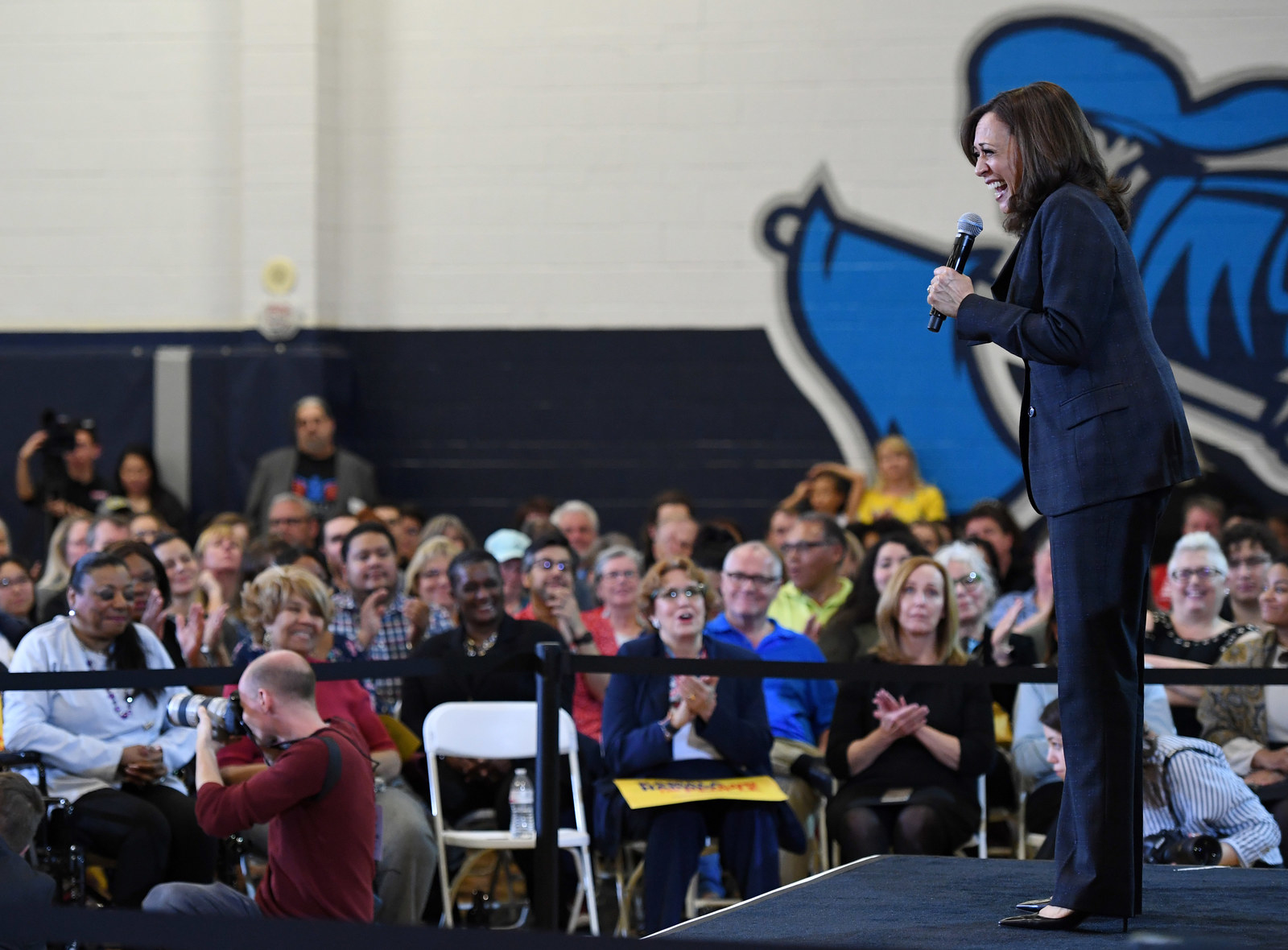

Jonathan Lamb, a meteorologist in West Ashley, South Carolina, attended an event for Sen. Kamala Harris in February to “get a feel for whether she’s electable — though I don’t know how you quantify that.”

“I put a lot of weight into how they speak,” he said. He was passionate about lots of “political hot potatoes,” like gun control and reproductive rights, but in the end, his decision would come down to one thing: “I’m just trying to imagine this person debating Donald Trump, and how they would hold up.”

Anita Wilkie of Plymouth, New Hampshire, said her priority was to find a candidate who could beat Trump in 2020; she had been making the rounds to candidates’ early events, looking for someone who she thought would be electable.

“That’s it, that’s exactly it,” she said at an event for Sen. Elizabeth Warren in February. “I was telling my sister this morning, ‘I know each candidate is not going to agree with what I want; it can’t happen that way. It’s the electability.’”

“It’s gotta touch me, not just in my heart, but in my gut.”

But what “electability” would look like, Wilkie couldn’t quite say. “It’s gotta touch me,” she said. “It’s gotta touch me, not just in my heart, but in my gut. I go by my gut feeling.”

On the eve of the 2018 midterms, the center-left think tank Third Way, which has opposed many far-left policies, posed a question for Democrats and independents in battleground districts across the country. To win future elections, would they want to see the Democratic Party “move to the left to generate enthusiasm” or “appeal to a broad range of voters, including people who may have voted for Donald Trump in 2016”? Seventy percent of respondents said they wanted the party to seek broad appeal instead of move to the left; the think tank touted it as evidence of support for their politics.

Voters in New Hampshire and South Carolina often spoke of “broad appeal” too — something many said was the most important thing for a candidate to have in order to beat Trump. But they didn’t see appeal as Third Way envisioned it — as a choice between policy directions.

Many voters looking to find a candidate with “broad appeal” said they were looking at the way candidates spoke — hoping to find someone who “phrased things in a mainstream way,” as one voter said, or who “emphasized the working people.” Others said they were looking at who appealed widely by speaking to the concerns of racial minorities; one said that to him, “broad appeal” meant speaking better to white women.

Electability was “absolutely” important to Kathy, a university employee who attended an event for Warren at Plymouth State University in New Hampshire. “They have to be able to speak to everyone’s concerns, not just a narrow segment,” she said.

That ability wasn’t rooted in whether someone was progressive or moderate, Kathy said. “In the age of Trump, the way you talk about things is really important. Even more than what you say, it’s how you say it.”

Some pollsters have set up Democrats for a conflict between prioritizing the issues they care about and doing whatever they can to beat Trump. Monmouth, in February, asked whether Democrats would prefer “a Democrat you agree with on most issues but would have a hard time beating Donald Trump” to one who they did not agree with but could more easily defeat Trump. Most picked the Democrat who would beat Trump more easily.

But in interviews, most Democratic voters rejected the idea that the two choices were at odds. Progressives, especially, said they thought that being on the far left edge of issues would be a boost against Trump, rather than a hindrance. Some said they thought progressive policies themselves were the missing piece to a candidate who had “broad appeal.”

“I’m not interested in a moderate who will back down. I think that’s the mistake we made in 2016.”

Electability is “someone who’s not afraid to be a Democrat,” said Heather Levine, a teacher in North Charleston, South Carolina, who attended a Harris rally in February. “I’m not interested in a moderate who will back down. I think that’s the mistake we made in 2016. We didn’t get that excitement going. It needs to be about policy.”

Few Democrats said they saw a reason to compromise on the issues that were important to them, like health care — even as they sought, first and foremost, to find someone who could win the next election.

Austin Atkinson, a sports agent in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, said he didn’t need a candidate who agreed with him on many issues. A lifelong Republican with little love for Trump, he’d come to an event for Harris in a South Carolina gymnasium to judge the “energy” around Harris’s campaign. Could Harris beat Trump? “That’s why I’m here,” he said, “to see.”

It didn’t bother him that Harris, who supports progressive policies like Medicare for All and the Green New Deal, was far to the left of him on many issues.

“I just need someone who will stick to their guns and represent the people that elected them and not cater to special interests,” Atkinson said. ●