Graduate students, not undergrads, are increasingly driving the country's student debt crisis, and the federal government will likely end up footing much of the bill, according to a study released today by the New America Foundation.

Most studies have historically lumped together undergraduate and graduate debt, leading politicians and media reports to focus primarily on the high price of bachelor's and associate degrees. But when graduate debt is isolated, as it was in this study, a striking picture emerges.

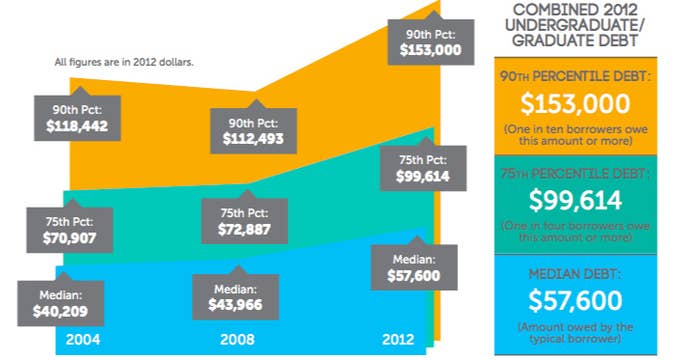

Around 40% of the more than $1 trillion in outstanding student loans went to financing graduate and professional degrees, the study found. Combined debt levels of the average graduate borrower, according to the study, have surged by $17,000 — from $40,000 in 2004 to more than $57,000 in 2012, adjusted for inflation. For the average undergraduate borrower, that increase was just $7,580, according to the separate New America Foundation report.

While the higher debt level is more manageable for medical school students, for instance, it could be crippling for Master of Arts students, among whom the median debt is $58,000.

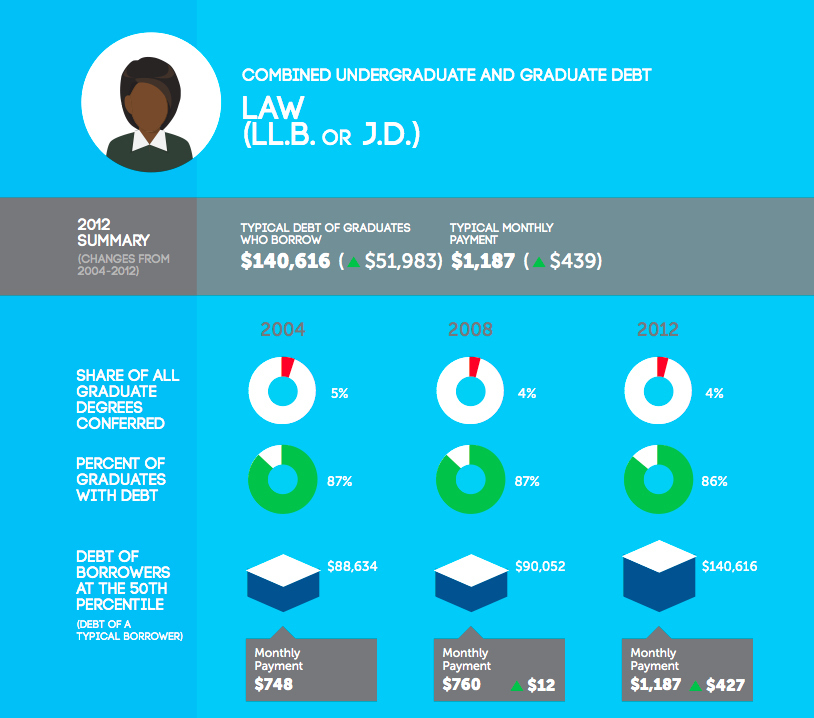

Some of the study's more eye-popping statistics pertained to law school students, whose job prospects are famously declining. The level of indebtedness for this group rose by more than $50,000 from 2008 to 2012, with the typical law student now owing $140,000, the study found — a jump that's unprecedented in any other field, including medicine.

"Most of these degrees are not intuitively worth it. They're not gateways to the middle class," says Jason Delisle, the study's author. "Is a Master of Arts degree really worth $20,000 more than it was in 2004?"

But thanks to changes in repayment terms, the federal government is likely to end up bankrolling many graduate degrees.

With an eye toward easing debt burdens in the wake of the financial crisis, the federal government began to offer income-based repayment plans and even total debt forgiveness for some students. One especially generous program forgives outstanding loan balances for graduates working in so-called "public service" jobs after just 10 years of income-based repayment plans. Public service sector jobs make up a full quarter of the workforce, according to a study by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, meaning huge numbers of graduate student borrowers will be eligible to have their debts forgiven after 10 years.

"People entering repayment programs with these kinds of loan balances have set themselves up to have the loans forgiven," Delisle says.

Other data suggests that graduate students are some of the biggest users of the federal government's debt-easing policies. An examination of outstanding student debt by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau found that those enrolled in the government's income-based repayment program had an average loan balance of $48,500 — more than triple the balance of those on a straightforward 10-year plan.

"That data does suggest that graduate students are using the plan more heavily, because the average balance is in excess of normal borrowing," says Rohit Chopra, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau report's author.

The Department of Education did not respond to a request for comment.

There are a variety of explanations for the sharp rise in graduate debt, from the 2008 financial crisis — which left students with fewer resources to fund their educations — to rising tuition prices. But Delisle also draws a connection to the government's policies, which he says may inadvertently be making borrowing huge sums easier and more feasible for graduate students.

"The Obama administration says they're addressing the problem, but it's also one they've helped cause," Delisle suggests. He points to the example of President Obama's push to eliminate the third year of law school, which many say is unnecessary and adds too much to students' debt burden. The administration's policies also make that the year most likely to be free under loan forgiveness, Delisle alleges, removing an incentive for both students and colleges to advocate for change.

"They're saying 'we have a huge debt problem,'" Delisle says, "but at the same time, they're saying to grad students, 'Borrow as much as you want.'"