When Hurricane Maria crashed into Puerto Rico on September 20, I knew I would have to go back. I had not been to Puerto Rico since I was eight. My recollections of the island were the scattered sense memories of childhood — my sweat on the clear vinyl slipcovers that protected the couches in my grandparents’ house in Bayamón, uncomprehended Spanish cartoons, the competitive clack of dominoes, the stringy texture of sugarcane that my abuelo cut for me from the field behind his house, a panoply of cousins whose faces I barely recall.

Otherwise, until a few years ago, I lived both mentally and physically far from the island. My Spanish was poor. I did not “seem” Puerto Rican, non-Puerto Ricans liked to remind me, though they never defined what that meant. I believed them anyway, until I stopped “seeming” Puerto Rican even to myself. Then Maria hit me with a force I could never have imagined. Obsessively, I watched the images of desperate people drinking from springs and wading through floodwater while the San Juan mayor, Carmen Yulín Cruz, said through tears that the country she knew was no longer, until I bought a round trip plane ticket to San Juan for 10 times the pre-Maria price, loaded two suitcases with D batteries and water filters, and boarded a plane entirely filled with Puerto Ricans — each as weighed down as I was — who were returning to their country.

By October 2, the day I arrived in Puerto Rico, San Juan had stabilized into a new abnormal. The streets were pitch black, almost no one had power or water, endless lines formed for necessities, and in hospitals, generators were low on diesel and oxygen was running out — but cellphones worked there, kind of. Governor Ricardo Rosselló had lifted the liquor ban he imposed after Maria. A few restaurants had started to open in Santurce and the wealthy neighborhood of Condado, and customers were bringing power strips to charge vast retinues of devices. Rosselló also pushed the 6 p.m. curfew back to 9 p.m. This did not help the small bars and restaurants that had already, I heard, gone bankrupt in the previous 12 days.

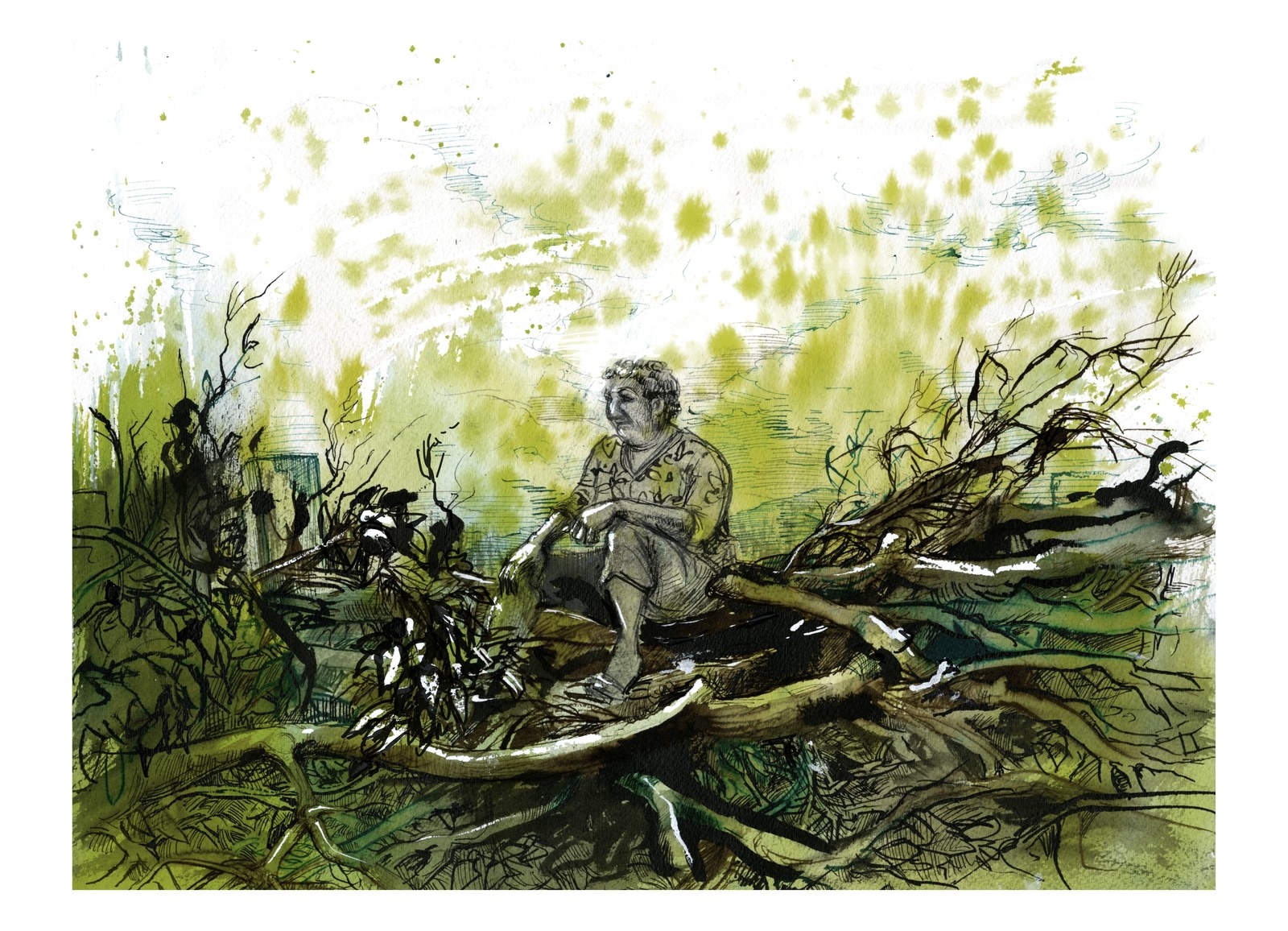

Everyone knew the real crisis was going down in the countryside, but the knowledge of its magnitude was blunted by lack of communication. Phones, let alone internet, didn’t work outside of the vicinity of San Juan, and 14-hour lines at gas stations helped keep people in place. The news trickling out was bad. I heard stories about elderly people thrown out of nursing homes after the power went off, patients dying in ER wards when the generators ran out of fuel, people crowded in hurricane shelters with no toilets. Eighty percent of the island’s crops vanished. The mighty El Yunque rainforest now seemed made of matchsticks. Homes had flooded or turned to tinder and their zinc rooftops blew off. No power, no water, no FEMA, no government above the municipal level, little to no outside help.

I met up with Christine Nieves at a coffee shop in Santurce, where she was checking the internet with her boyfriend, the musician and activist Luis Rodríguez Sanchez. Christine and I had first met two years before at a creative conference and kept in touch. A 29-year-old native of Ponce, in Puerto Rico’s south, Christine moved back to the island a year ago from Tallahassee, determined to help build her country.

After falling in love with Luis, she moved to his hometown, a small mountain town called Mariana, in the municipality of Humacao. On Facebook, she posted photos of the valley outside her balcony. Jungle, sky, technicolor flowers.

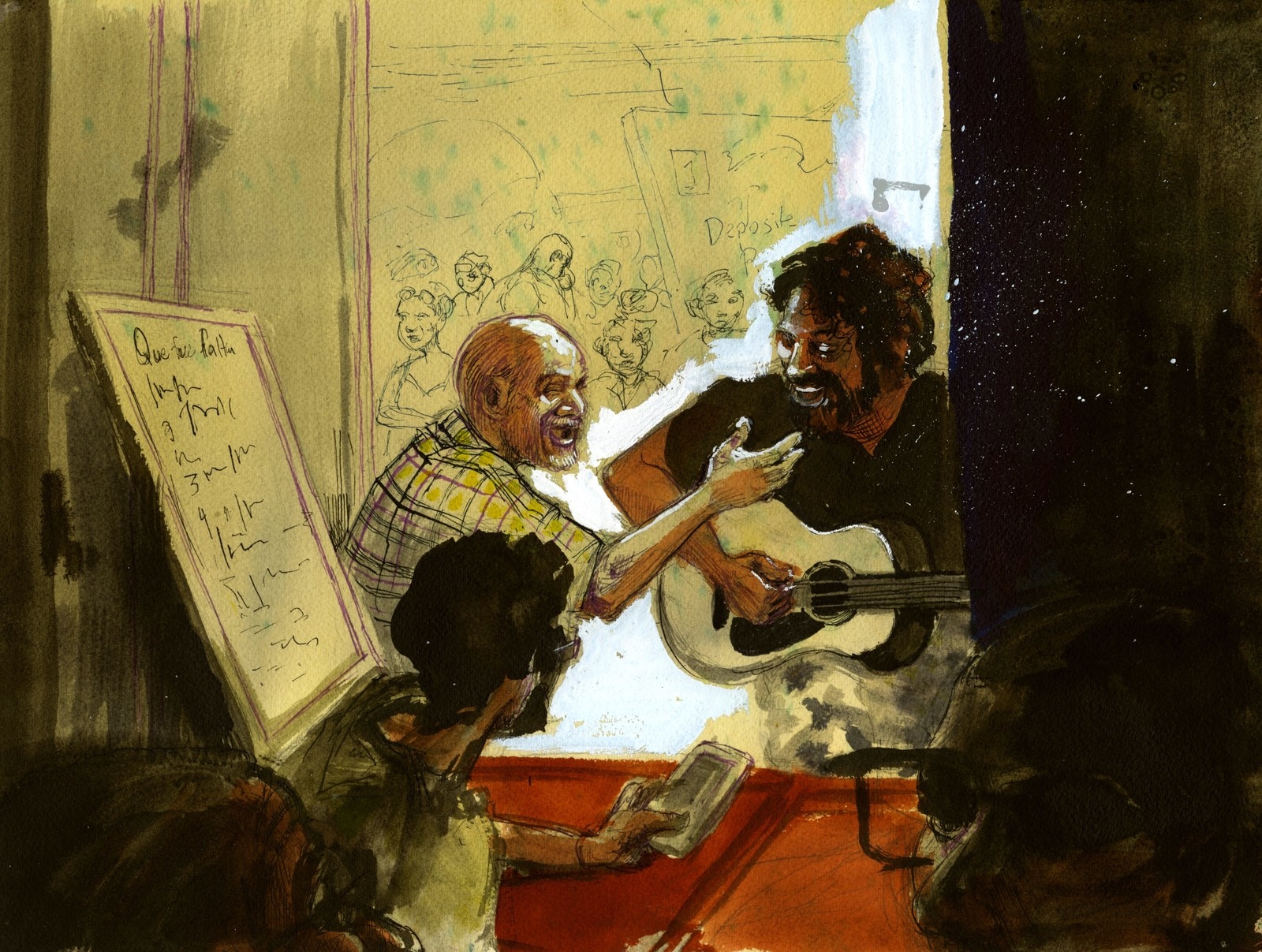

Christine spent the hurricane in the tiny bathroom beneath the staircase, with Luis, his cousin Omar, two dogs, and a cat. The power died. The windows shattered and the walls screamed. The exterior doors snapped open under pressure, filling the house with rain. Luis played his guitar. Omar played his drums.

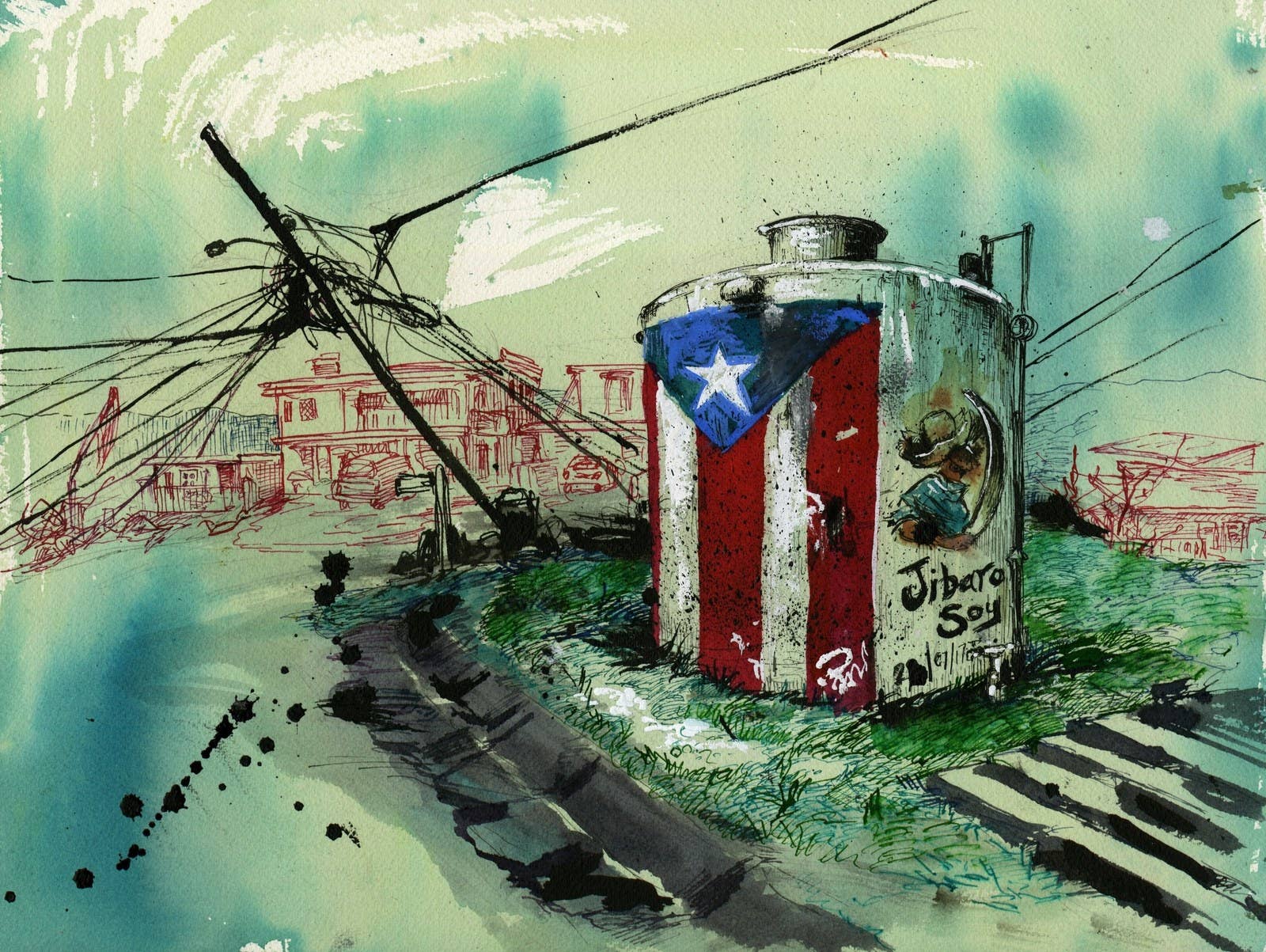

When they finally stepped out, they saw that their beautiful valley was now naked. They had neither electricity nor water nor cellphone signal. Their ground floor was flooded with glass-laced water, their fruit trees had toppled, and their reservoir tank had drained, but, except for broken windows, their house was basically intact. On the blasted tree in their courtyard, they raised a Puerto Rican flag.

After a week of cleaning out their flooded home, FEMA had not come, potable water was running out, and what food remained was rotting in people’s refrigerators; one of their elderly friends had confessed to eating spoiled ham. Christine and Luis came up with an idea.

Some of the couple’s friends were involved in comedores sociales, or social kitchens — soup kitchens in which those who ate generally also helped, and which were organized in the spirit of solidarity and mutual aid rather than charity. A comedor social had already sprung up in Caguas, a city not far from San Juan, where it was feeding hundreds of people every day. Christine and Luis decided to learn from their model and apply it to Mariana.

“Before the storm, I knew political work should be done through food,” Christine told me, “but I had never taken the responsibility for talking to people and organizing. After the hurricane, the devastation was so great we needed to start.”

After I met up with Christine and Luis in San Juan, we drove 45 minutes to Caguas, where we visited El Centro de Apoyo Mutuo, which may be the prettiest soup kitchen on earth. In front of a squat building, whose signage was painted the same bright tones as the candy-colored streets, perhaps a hundred people queued beneath shade tents. A guitarist sang for them, and an old man danced along with him. Organizers had even laid out coloring books for kids.

Inside, the kitchen was a hive of activity. Two young men staffed a table soliciting donations, while working-class older folks stood alongside tatted-up punk girls and spooned delicious arroz con gandules. Diners ate at long tables, washing the food down with lemonade. While they ate, many women cooled themselves with Spanish fans. In the stupefying heat, there was neither electricity nor running water, but there was beauty and community.

In the back sat piles of donated food, all given by locals. Neither government nor NGOs provided for El Centro. This was not charity, given by the high to the low, but mutual aid, provided by the same people it was meant to serve.

El Centro was organized by seasoned activists: veterans of student strikes, workers’ strikes, and protests against the US bombing of Vieques, and the décor and clothes showed the usual symbols of Puerto Rican nationalism — the black and white flag that indicates opposition to US-government-imposed austerity, and the cardboard cutout of independence fighter Oscar López Rivera (himself a volunteer at the kitchen). As Christine and Luis took notes, I spoke to Kique Cubero Garcia, one of El Centro’s organizers. “My philosophy is to work with the people to give them the tools and experiences of self-organization,” he told me. “Instead of taking power from the top, from institutions, we prefer to make changes from the bottom.”

As we drove the 23 miles from Caguas to Humacao, the cellphone signal dropped. Humacao was the first municipality Maria hit. The storm’s eye fell over the beachfront town of Punta Santiago, sending the sea flooding till it met the river, destroying cars, homes, roads, and possessions in a torrent of sewage and salt. We passed downed trees and telephone poles and destroyed houses, but the roads were clear, thanks to barrio residents and crews of workers hired by Puerto Rican companies.

Puerto Rico’s economy (itself malformed by over a century of colonialism) has spent the last several years battered by a debt crisis and US-government-imposed austerity. With unemployment high, one-third of Puerto Ricans receive EBT (the card version of food stamps), but, without power or internet, stores could not process their cards. Credit cards didn’t work, either. Communication was one-way, doled out by the single functioning radio channel, on which pharmaceutical companies made announcements to tell their employees whether they should show up for work. Those employed by smaller companies were often out of luck. Lines at ATMs stretched for hours, but with so many workplaces closed, and workers unable to get to those that were still open because they lacked gas, the savings of already cash-strapped people began to dwindle. In Humacao, friends and family kept each other alive.

Outside the car window, people waited in endless lines before ATMs, grocery stores, gas stations, and drug stores, and behind them lay an infinity of naked trees. The car wound up the roads until at last we reached Barrio Mariana.

A village of 3,300 clinging to hills of the Cordillera Central, Mariana is best known for its annual breadfruit festival. It is a poor town, and elderly, whose residents largely work in Humacao’s pharmaceutical factories, or collect social security. Some supplement their income by brewing cañita (illegal moonshine). Mariana’s homes were battered concrete boxes, surrounded by downed trees and curling ruined power lines. Many flew the Puerto Rican flag. Someone — an elderly woman, I later learned — scrawled “SOS Agua Comida Mariana” on the pavement.

The municipal government did not visit Mariana until September 30, 10 days after Maria. A truck pulled up at the bottom of the hill, and when people spent their scarce gas to drive down to it, they were handed two small bottles of water, a tin of Virginia sausages, a Nutri-Grain bar, and a pack of tropical Skittles. More aid, in the form of MREs and water delivered by the military and the FBI, would not arrive again until October 8.

Luis was born in Mariana. His grandfather cut sugarcane and brewed cañita, using the money to buy a plot of land that he divided between his 12 children. Luis moved away for university, but returned 20 years later, and now lives on that same plot, across a hill from his aunt, in a house owned by his father, who designed its airy expanse of skylights, balconies, and tea green walls. Luis’s father was an intellectual and activist — he founded a community organization that was the predecessor to the 30-year-old Communal Recreational and Educational Association of Mariana (ARECMA), organizers of the famous breadfruit festival. Luis and Christine knew ARECMA would be an essential partner in setting up a comedor social.

We stopped in the backyard of one of ARECMA’s founding members, Ruli Laboy Abreu, to discuss their plans for a kitchen. Ruli was a broadly built man in his fifties, a devoted communist who had spent countless unpaid hours building La Loma, ARECMA’s community center, and cooking feasts for the breadfruit festival. His face conveyed strength and vitality, but he moved with difficulty; even before the hurricane, his bad knee had needed surgery, and now, with all the extra physical work, he could barely walk. He helped clear hurricane debris anyway. “Ruli’s the type of person who will keep working even if he doesn’t have limbs to do it,” Christine told me later.

“Camaradas,” Ruli called us, his smile generous. His sweat-soaked T-shirt bore an image of Oscar López Rivera. He led us to a garage where he was fixing up some cars. From a crowded corner he produced a huge bunch of plantains, then severed several neatly with his machete and offered them to us. Ruli enthusiastically agreed to Luis and Christine’s idea for the kitchen. “Que la patria te bendiga,” he told us as we departed: May the nation bless you.

In the first days after Maria, people in Mariana cooked all the food in their refrigerators to prevent it from rotting — great feasts of pernil shared with the neighbors, garnished with fallen avocados and washed down with coconut water from the palm trees that Maria had downed. As this food ran out, people shared their canned goods and whatever they could find at the nearly bare grocery stores, checking on relatives to see that they were fed. Those with underground cisterns shared their water with their neighbors. Water also came from communal taps, or from a spring that gushed from the mountain — though with rotting animal corpses leaking into the water supply, these sources became increasingly dangerous. To bathe and flush the toilet, we collected rain. Those lucky enough to have generators waited for hours to buy diesel.

These conditions hit the elderly hardest. In Humacao, I met Ivette Vazquez, whose 81-year-old mother had been kicked out of her nursing home after the building lost power, and she could no longer obtain her medicine. Ivette’s mother suffered from dementia and Alzheimer’s. She was a skeletal, silent figure who could barely eat the soup Ivette spooned into her mouth. “This is an urgent situation,” Ivette told me, her voice tight with exhaustion. “What are they waiting for?”

Days now revolved around the maintenance of life. Wake up with the sunrise, the insect bites, the stultifying heat. Fetch and purify buckets of water. Make coffee, if you have coffee, on a sterno. Wash clothing in a bucket, shower in a bucket, scrub dishes in a bucket. Clean out your hurricane-wrecked house. Clear the downed trees with a machete. Cook on a fire. Sleep at nine, because there is no light. Don’t get sick — the hospitals are hazardous because there are too many bodies rotting in the morgue. Don’t tell yourself it will get better anytime soon.

Against these difficulties, Luis and Christine began to carry out their plans for a comedor social. They didn’t just want to feed people, but to build a space that would kindle their senses of self-sufficiency, community, and pride. Several times each day, they climbed the hill to La Loma, ARECMA’s outdoor community center. Maria had smashed La Loma’s stage and playground, but spared the kitchen and water tank, as well as a massive mosaic with the words: “All Glory to the Hands that Work.” The ground was a chaos of felled trees. Small boys gathered and cleared the branches.

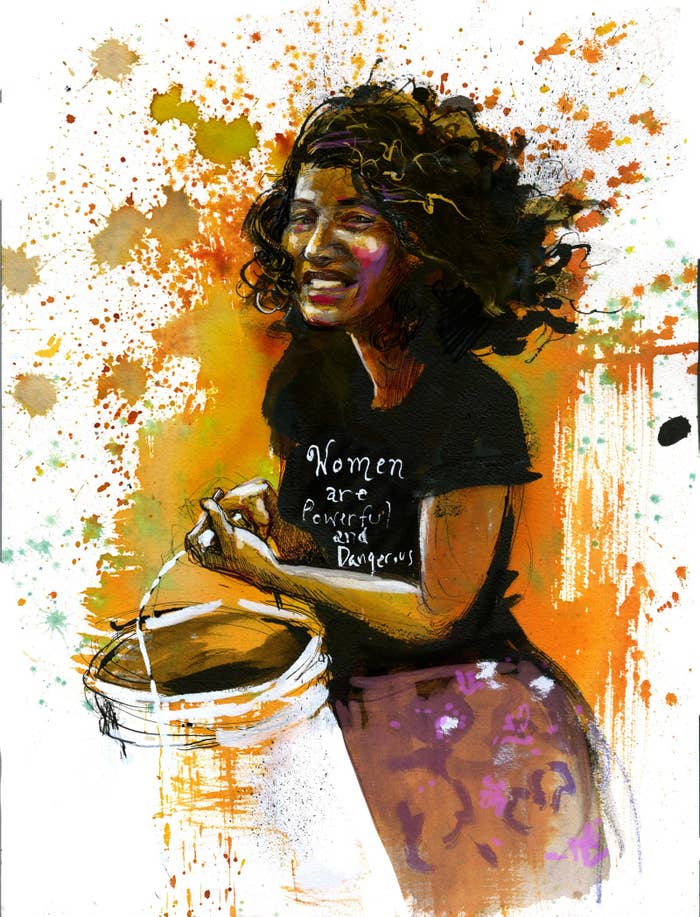

Because of ARECMA’s decades of work, Mariana has a strong tradition of self-organization, and with the help of Ruli, ARECMA’s board president Rosalina Abreu González, and others, resources began to appear. Someone had a truck and could get a tank of water. Someone else knew how to cook food for large groups. Others had paint and would make signs requesting donations and volunteer work, and explaining that the kitchen was made by and for the people of Mariana. Tech Lady Mafia, a feminist group for women in the US tech industry, sent Christine money, and other donations came in. Every few days, Christine and Luis drove down to Caguas, where there was cell service, and parked on the side of the road, sweltering in the sun, so that they could respond to potential helpers and Christine could post Facebook Live videos describing life in the village.

This human help contrasted with governmental neglect. Rosalina told us she had driven down to Humacao, the nearest large town, to ask a FEMA representative for water, but was told that they could not get her anything until they had approval from San Juan, which could not come until early next week. Meanwhile, shipping containers full of aid — including private donations from the Puerto Rican diaspora — sat untouched in the ports and warehouses of San Juan. The day after Trump made his only visit to the island, Rosalina arrived at La Loma furious. “He wants to humiliate us,” she said. “He went to one of the richest towns in Puerto Rico and threw toilet paper rolls at people’s heads.”

Over the last two weeks, Trump had called Puerto Ricans many things. They are “ingrates,” who “want everything done for them” — Latino and thus lazy colonial charges, pleading for the strong men of the US to keep them alive. He shamed them for a financial crisis “largely of their own making,” and threatened to pull FEMA, the military, and, bizarrely, “First Responders” from the island. Trump evoked a stereotype born in 1898, when the United States first took control of the island from the Spanish — and one that has reinforced the US government’s refusal to grant Puerto Ricans citizenship until 1917, or to let them elect their own Puerto Rican governor until 1947. For nearly 120 years, eminent US politicians and public figures have argued that Puerto Ricans are deficient children, too Spanish, brown, and feckless to be granted either independence or statehood. It doesn’t matter that the men, women, and children of Mariana cleared their own roads with machetes. A Puerto Rican is lazy because they are Puerto Rican.

That day, two women in a car stopped Luis as we walked down from La Loma.

“Are you from FEMA?” one asked.

“FEMA isn’t coming,” he answered.

A date was set. Mariana’s comedor social would open in four days, on Monday, October 9, with the goal of giving out about 200 meals. They would cook in La Loma’s kitchen, though it lacked running water. Rosalina had wrangled some water from the municipality to give out to drink. Luis would get a sound system from his music contacts in San Juan and use it to announce the kitchen. We drove down to Humacao, where an artist friend pulled a plastic table out to her lawn and we ate turkey legs and sweet amarillos by candlelight, a neighbor came by with a sack of lukewarm beer, and a Spanish version of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” played on the car radio.

The next day, we learned that the water at La Loma was gone.

Perhaps someone had stolen it, but logistically, it was far more likely it had been allowed to drain out of the tank, in a self-destructive gesture by desperate people angered that La Loma had water and they did not. “This just shows we need to have better communication with the community,” Luis said to Christine on the long drive down to San Juan to get supplies. “This mindset is an extension of colonialism, of scarcity, of the way the system is rigged against you,” she answered, sadly. It was the day of Mike Pence’s visit, and traffic snarled, with police blocking off entire neighborhoods. The internet signal snapped on, and they fell upon their phones, lines to their people, scattered around the globe, who would help when the government would not.

Like many activists, Luis and Christine saw in Maria the potential for change. “Hurricane Maria is an opportunity to see the power is in ourselves and not America,” Christine told me. “This is a great educational experience for us, to prove to ourselves we’re actually capable of rebuilding. That’s in complete dichotomy of generations on generations believing we needed another country to survive.”

On October 9, Proyecto de Apoyo Mutuo Mariana opened without a hitch. Former cafeteria workers helped cook the food. Friends drove in from San Juan with pickup trucks full of rice and beans and water. 145 people ate delicious meals, while Luis, Christine, and the other organizers collected their information and told them that this food did not come from the government, from FEMA, or from the United States. It came from the community itself. They plan to continue providing daily meals as long as they are needed.

“I keep going back to the stories we Puerto Ricans tell about ourselves,” Christine told me one night during my visit, as we sat on the porch of her house, listening to the coquíes sing in the vast and star-filled night. “They are very powerful but very dangerous. They can build us up or tear us down.”

“For a long time, we told ourselves we were lazy, because that’s the story we’ve been told,” she said. “That we’re not capable of building or managing the country. If you tell yourself that, you’ll start like it acting it is true. This moment when, literally, the lights go off, is a great opportunity for us to ask ourselves what stories we are telling ourselves, and what stories we want to tell.” ●

Molly Crabapple is an artist, journalist, and author of Drawing Blood: A Memoir. Her next book, a collaboration with Syrian war journalist Marwan Hisham, will be published by One World Random House in Spring 2018.