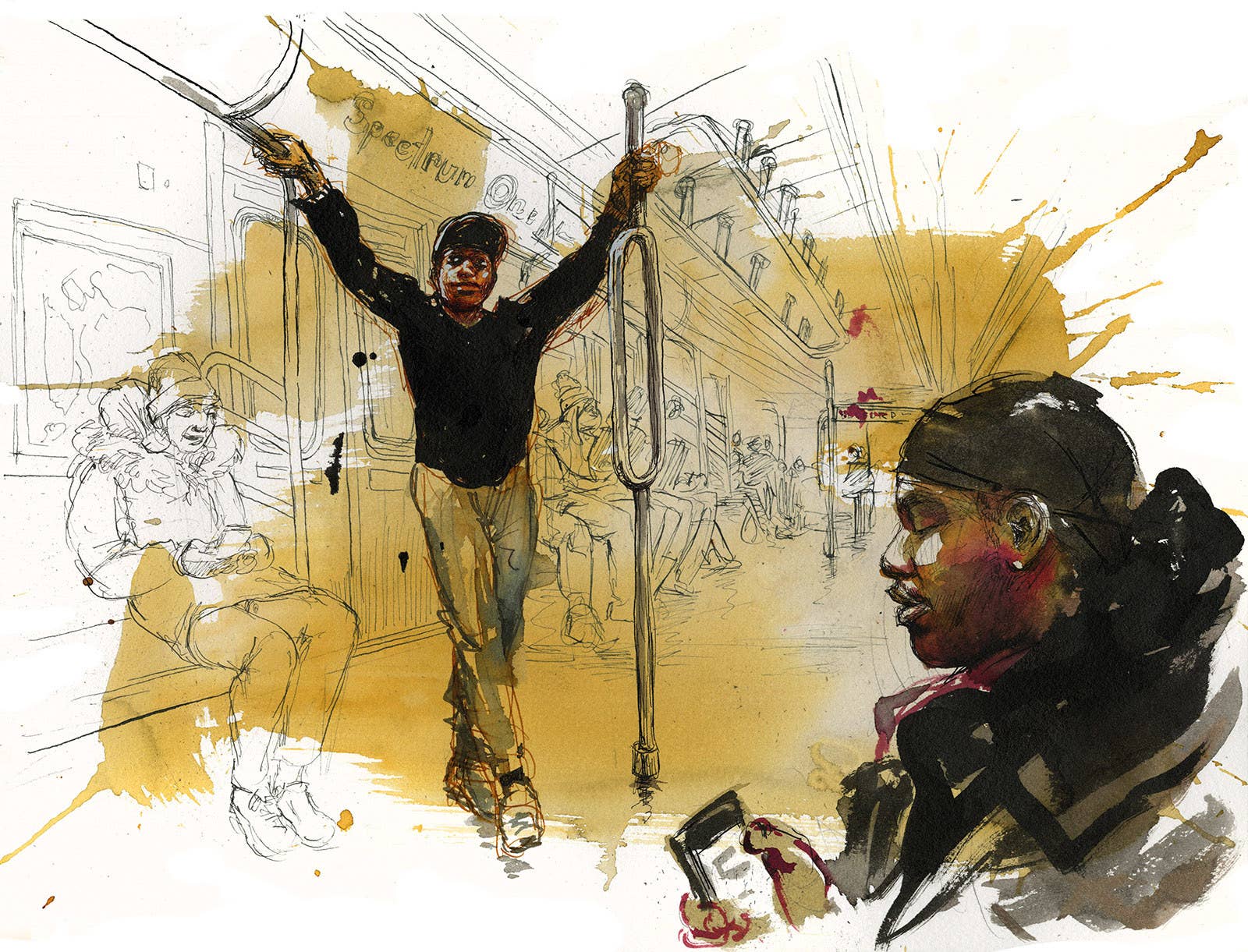

At 23, Sony Jayy has been dancing on the New York City Subway for a decade, and the L train is his and his friends’ kingdom. Sony and his friend Malik get on at Union Square. They trade quips until the train slides under the East River. That’s when the show begins. Sony strides down the car: “Me and my brother are gonna be dancing on a moving train. There won’t be any kicks to the face or the shinbones. If you like what you see, feel free to show support. I hope you all enjoy.”

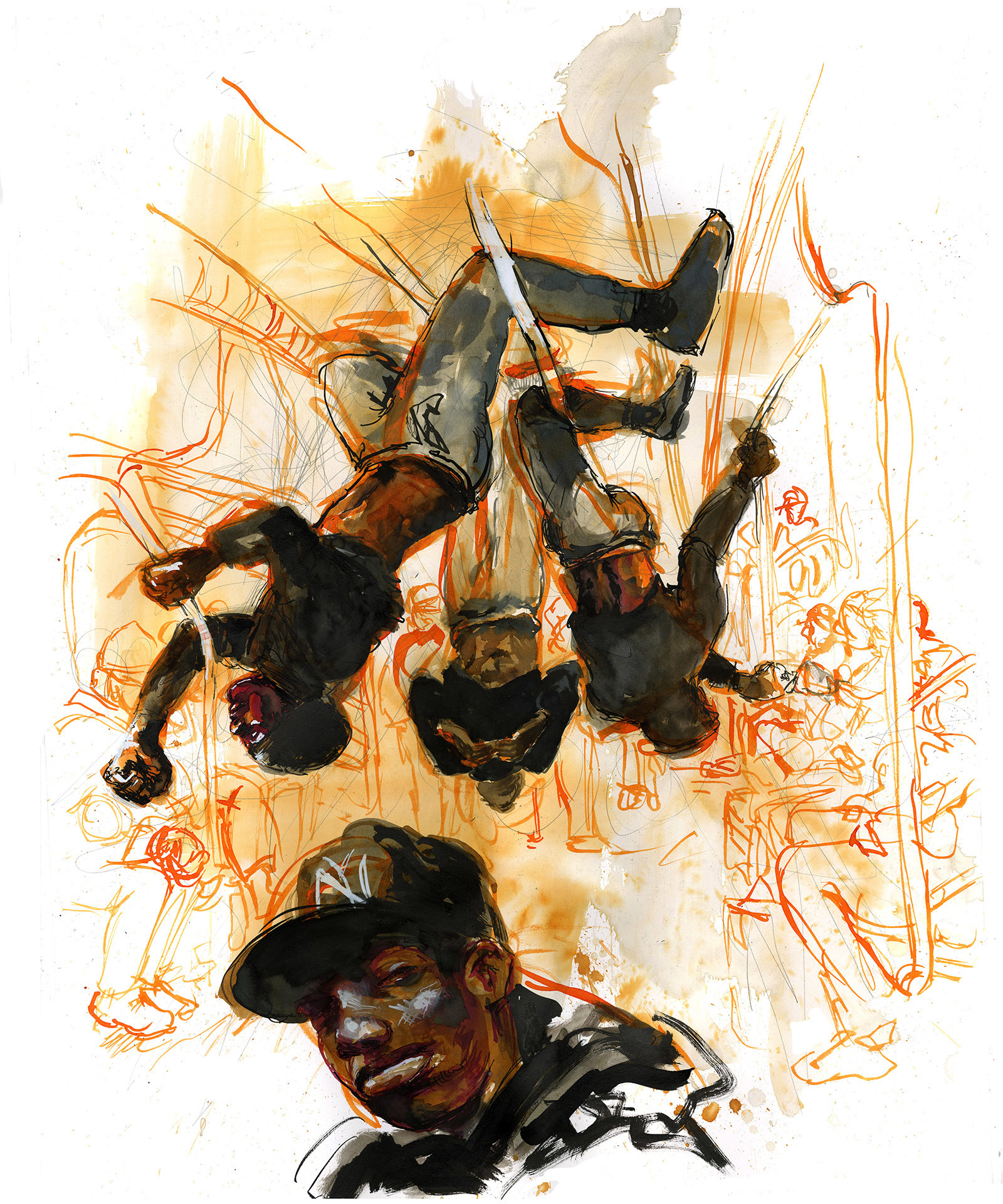

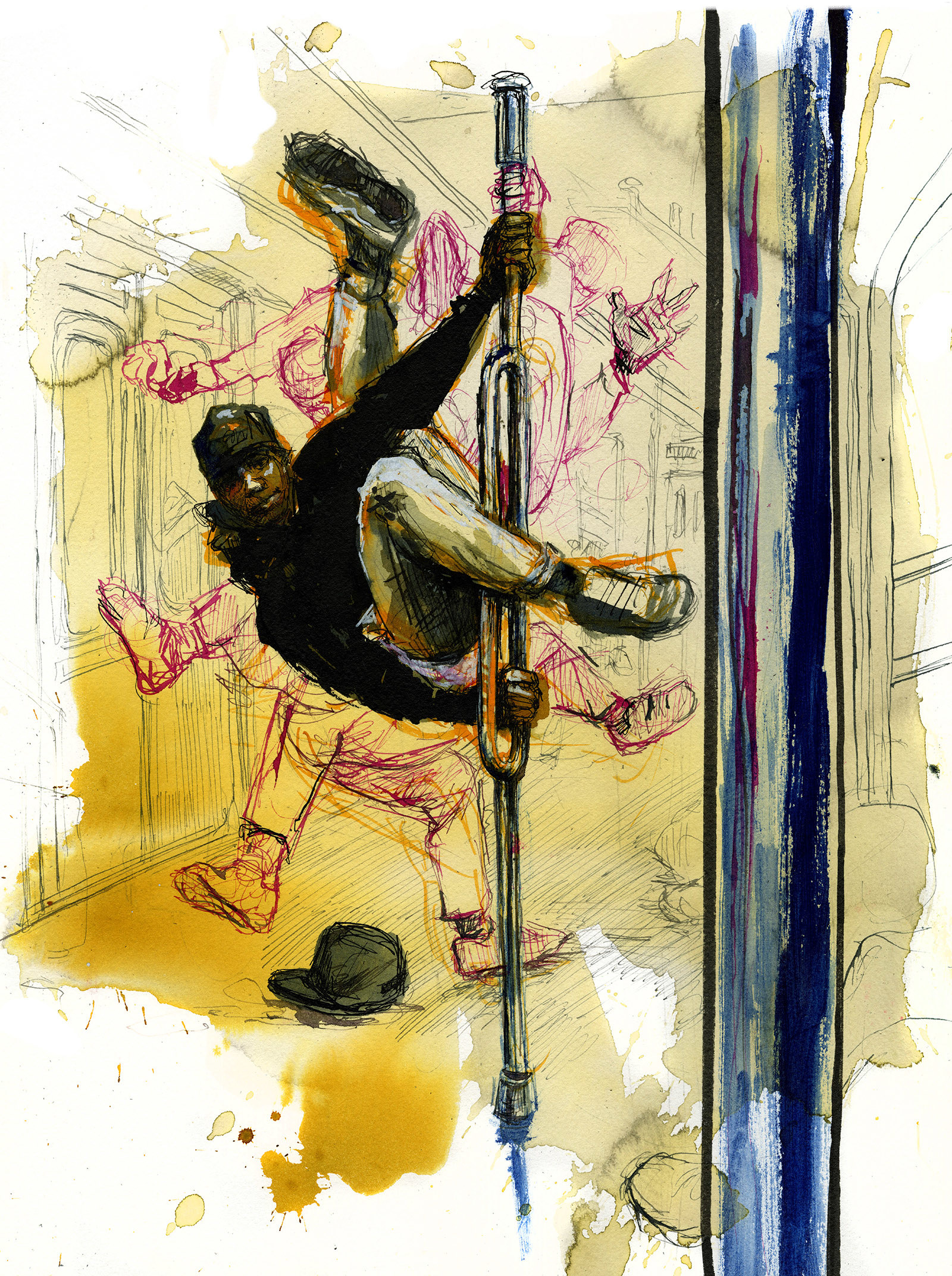

He flips on the stereo. The bass starts. Sony throws himself into the air.

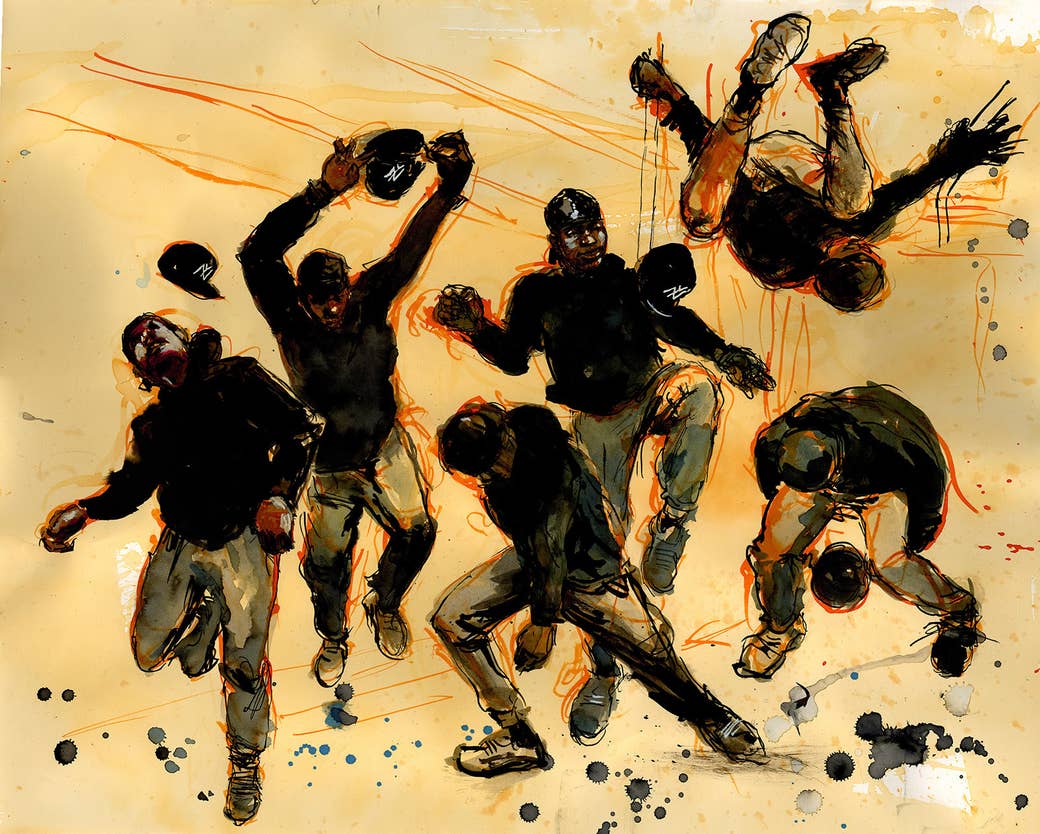

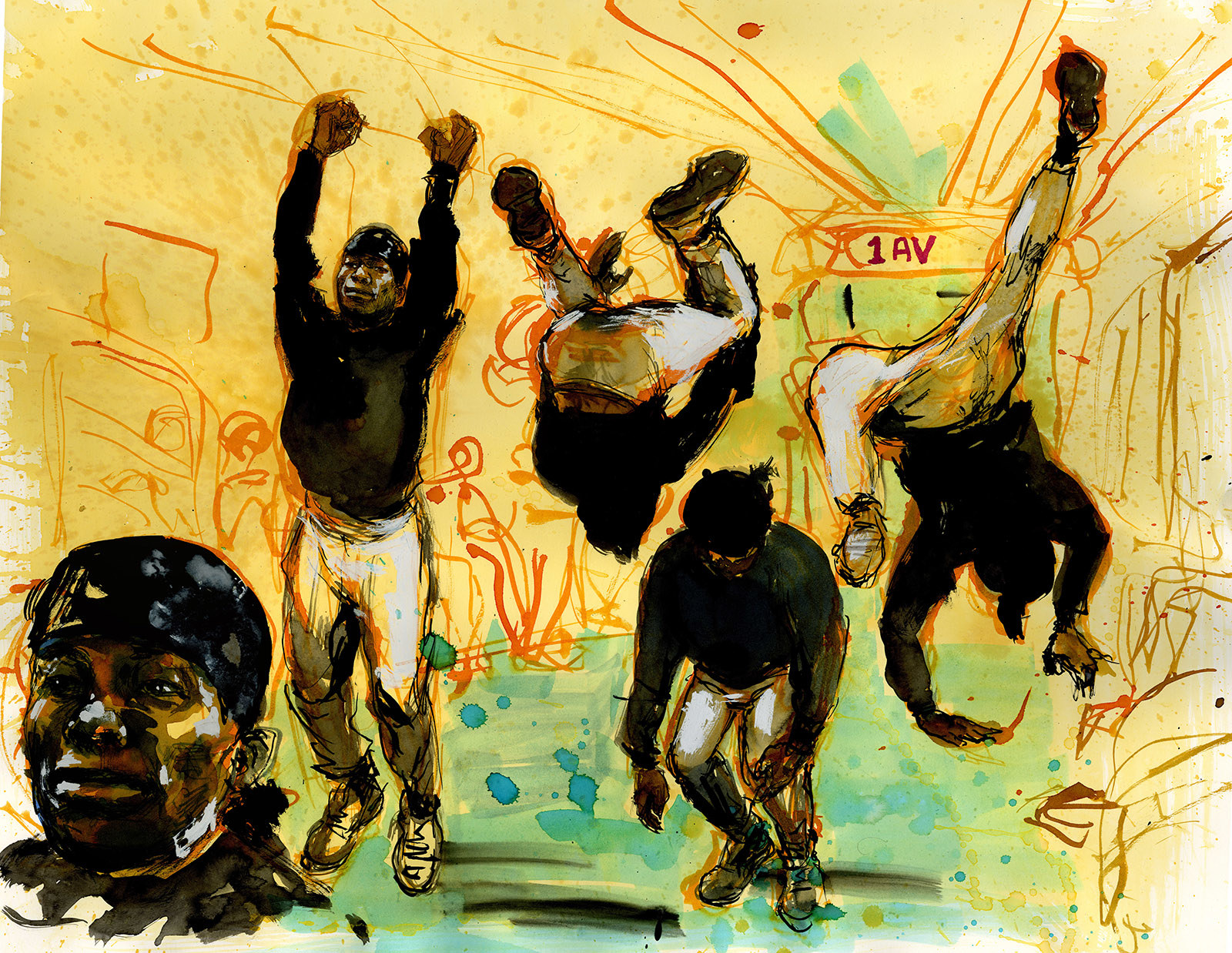

For the next minute or two there is no distinction between the lurching train and the athlete who spins on its poles, hangs upside down from its bars, and backflips down the center of the car. After Sony’s done, Malik follows suit. Their moves are part Cirque de Soleil, part Spider-Man, and 100% New York swagger. The act ends just before the train pulls into Bedford. They pass the hat, then get off, only to jump on a train headed back to Union Square. Once it goes under the river, they’ll do it all again.

Sony and Malik are litefeet performers. Litefeet is a style of hip-hop dance in which dancers use precision footwork, pole tricks, and props like hats to appear as quick and light as air. Because hundreds of litefeet dancers perform in subways, they have become a symbol of New York City. Most subway riders have seen the guys who shout “Showtime!” and kick, spin, and cartwheel perilously close to the faces of passengers in exchange for tips. To some people, they’re an intrusion, but to me, they’re the embodiment of working-class New York art.

Litefeet was born in Harlem in the early 2000s, with Mr. YouTube and Chrybaby Cozie as some of its earliest pioneers. At first, performers developed the style in schools and parks, but within a few years, they were doing it on the subway for cash. This got them noticed — in both good and bad ways. In 2014, Bill Bratton, then the New York City police commissioner, declared war on the performers. The originator of “broken windows policing,” Bratton saw the dancers — mostly young Black men — as having “the potential both for creating a level of fear as well as a level of risk that you want to deal with.” That year, the NYPD made hundreds of arrests.

You can’t stop an artist. In the years that followed, litefeet exploded. Stars like Kid the Wiz, Kid Pat, and the group W.A.F.F.LE have been flown around the world to appear in ads, music videos, and TV shows like The Ellen DeGeneres Show and America’s Got Talent.

Sony started dancing litefeet in 2012, before it broke through to the mainstream. He was 13 years old, and litefeet drew him in, he said, because of the authenticity of the moves, and the energy of the culture around it. He honed his skills at dance battles, where dancers competed for prize money; by 15, he was skipping school to dance on the trains. While he has performed onstage and in music videos, he still pays his bill by dancing on the subway. On his best weeks, he can earn as much as $1,000.

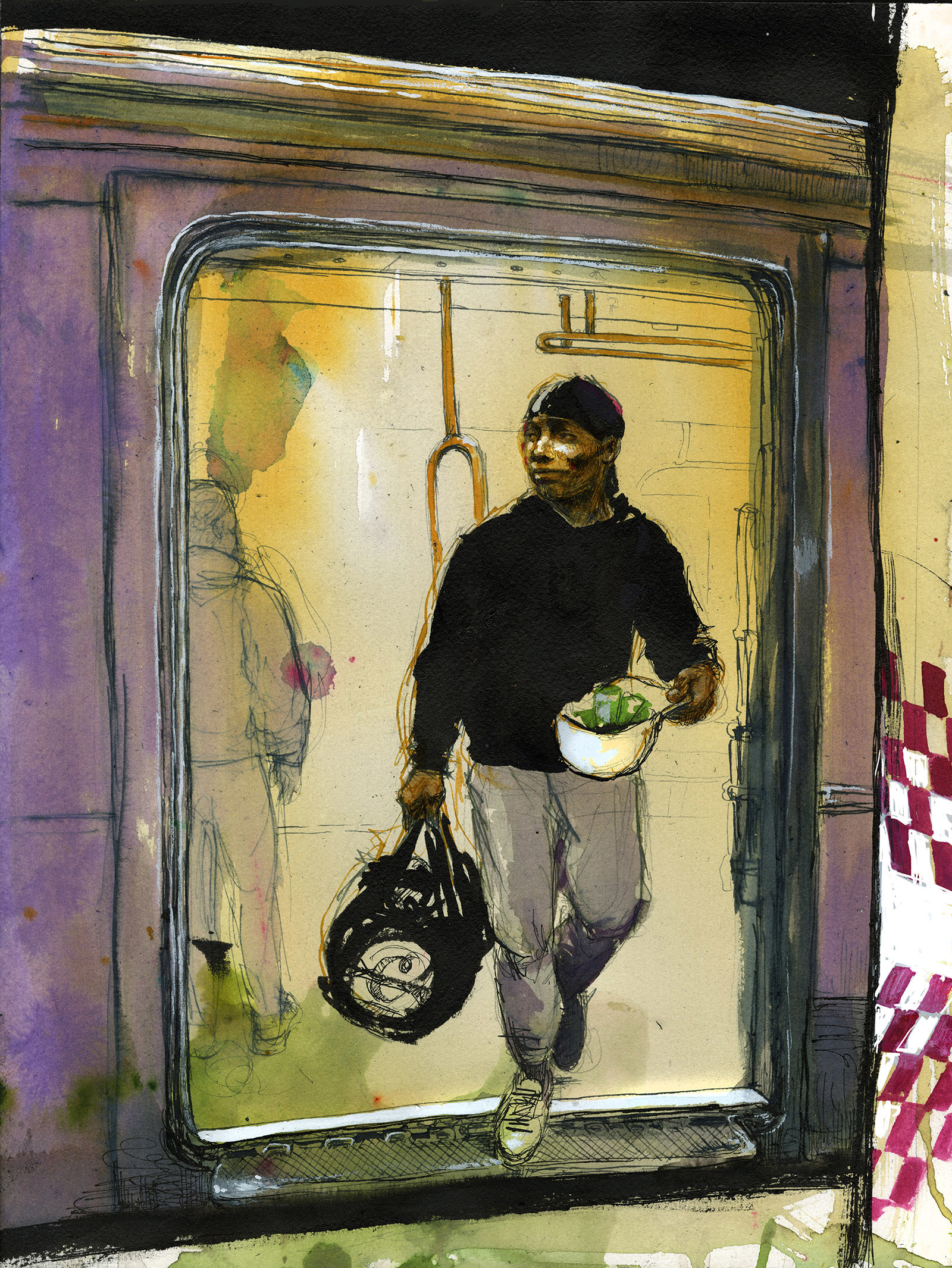

When I met Sony and Malik on a Union Square subway platform, they had already been at it for five hours. Though they must have been exhausted, they were charming and generous with their time. At first, they did it for the love, Malik told me. Now it was a job. Six hours a day at least, five days a week. Afterward, Sony trains a few hours more at the Brooklyn Zoo, a graffiti-bedecked gym whose spring floors and Olympic-size trampoline have made it beloved by acrobats. Theirs was the sort of discipline expected of ballet dancers or professional athletes, and as I followed them from car to car, I marveled at their stamina. Their bodies were used to it, they said. Sometimes they got injured; Sony had tweaked his ankle a few weeks before. And the new designs of the trains made it harder. Some dancers dropped out after a bifurcated pole was introduced, which stopped easy spins and forced them to rely on pure muscle.

The hardest part of the job was dealing with ignorant people, Sony said. Some passengers tried to interrupt his show or smack his hat out of his hands when he was doing tricks. “You have to keep your composure. You can’t let them drag you down.”

It took a long time for litefeet to get recognition, he told me. Social media helped. Performers went viral from TikTok and Instagram Reels. And business was coming back after the dead days of COVID.

I asked him what he wanted for the future. “Damn sure not dancing on these trains,” he responded. He wanted to study a trade, save his money, and give classes on the side teaching calisthenics and acrobatics.

The train went under the East River, and Sony flipped on the music.

“One song. Hope you enjoy. God bless, Happy New Year’s, people.” The beat started. He reached up, grabbed the bars traversing the train car, and flipped himself over to hang from his ankles like a pendulum, giving fist bumps to the seated flotsam of Williamsburg.

“It’s not easy to fight gravity,” he told me later, grinning and wiping the sweat from his forehead. ●

This story was produced with the support of the Economic Hardship Report Project.

Molly Crabapple is an artist and writer based in New York. She is the author of two books, Drawing Blood and Brothers of the Gun (with Marwan Hisham), which was long-listed for a National Book Award in 2018. Her reportage is the 2022 winner of the Bernhart Labor Journalism Award and has been published in the New York Times, New York Review of Books, the Paris Review, Vanity Fair, the Guardian, Rolling Stone, the New Yorker, and elsewhere. Her art is in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art. Her animations have been nominated for three Emmys and won an Edward R. Murrow Award.