For nearly five years, militant Islamist group Boko Haram has been waging a violent insurgency in northeast Nigeria. The fighting has killed more than 4,000 people, displaced 500,000 more, and destroyed hundreds of schools and homes.

Nigeria, an oil-rich country in West Africa, gained independence from the British in 1960. Under colonial rule, development was centered primarily in Nigeria's south. The legacy of neglect in the north continues to affect lives today.

Today, many Nigerians are poorer than at the time of independence, according to the International Crisis Group. Government services like electricity, roads, security, water, health, and education are absent for many, especially in the north.

A man walks past burnt buses in northern Nigeria after two suicide bombers' attacks on March 19, 2013.

Persistent government corruption, police impunity, and regional conflicts continue to undermine reform efforts. Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan has tacitly acknowledged Boko Haram may have infiltrated Nigeria's government.

In these circumstances, Boko Haram (roughly meaning “Western education is forbidden") thrives. The group wants to establish an Islamic state in the north that adheres to Sharia law. It has denounced the Nigerian government's “false Muslims.”

The meaning of Boko Haram is a bit more complicated: Read more here.

The group's history remains disputed. The charismatic Nigerian Mohammed Yusuf started Boko Haram in 2002. He reportedly had support from some politicians. Yusuf also mentored Boko Haram's current leader, the violent Abubakar Shekau.

Police have detained and interrogated Yusuf several times but never arrested him, reportedly because influential officials intervened on his behalf. Yusuf also reportedly had financial support from other Salafi extremists, like Osama Bin Laden.

Nigerians react at the site of an alleged Boko Haram Church bombing in 2011.

Over time, Yusuf and Boko Haram radicalized, and the Nigerian government targeted the group. At the same time, Boko Haram also gained popularity for calling out government failures and corruption, and for aiding unemployed youth.

Then in 2009, a series of clashes between Boko Haram and Nigerian police escalated into an armed insurgency against the government in the north. At first, Nigerian troops beat Boko Haram and killed hundreds. They also arrested, and then executed, Yusuf.

But the government's military response only temporarily impeded Boko Haram, which went underground. In 2010, the group started to retaliate for the 2009 campaign with attacks on the police and military, including suicide bombings.

In the years since, Boko Haram has intensified its terror campaigns to target Christians, Muslim clerics, local leaders, the United Nations, health workers, bars, and schools — and to kidnap and enslave girls. The government often denies reported attacks.

Last spring, President Goodluck Jonathan declared a state of emergency in the Boko Haram strongholds, giving the federal government more power. Troops deployed and, with help from local groups, pushed Boko Haram out of many cities and towns.

Again the military's response has not stopped the violence. Instead, as the military retreated, Boko Haram grew increasingly brazen in its civilian attacks. It laid siege to towns, burned villages, and kidnapped kids, in addition to orchestrated bombings.

In November, Human Rights Watch reported that Boko Haram was kidnapping and raping girls in the north. It also documented the group's use of child soldiers. Witnesses told HRW the attacks intensified after the state of emergency was put in place.

Nigerians have criticized the government for failing to keep Boko Haram out and to address long-standing issues of underdevelopment and corruption. Police have harassed and arrested those with no Boko Haram connection, further raising anger.

Exploiting a political and security void, some Boko Haram members have dispersed to neighboring Niger and Cameroon, where authorities are also poorly equipped to fight the radical armed group, which feeds off grievances in neighboring countries.

Then on April 14, a deadly bomb ripped through a bus station in Abuja, killing at least 71 people. It was the capital's worst terrorist attack, and all signs pointed to Boko Haram. Already that week, Boko Haram had reportedly killed 64 in the north.

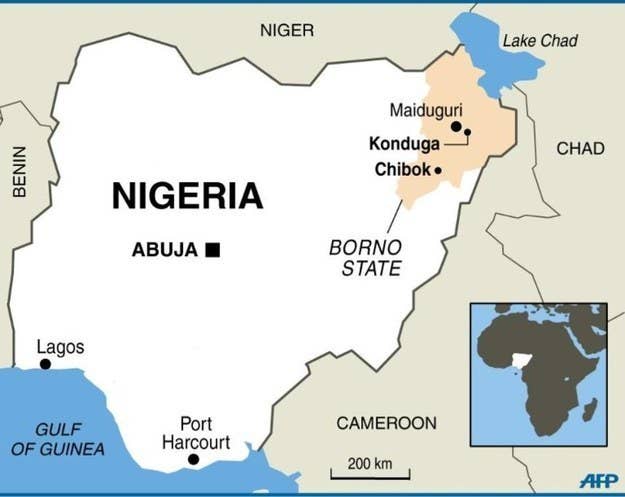

Around midnight, Boko Haram struck again. Masked gunmen stormed a girls school in Chibok in Nigeria's rural northeast. They dressed as Nigerian soldiers, ordered the unsuspecting girls into trucks, and drove off to their hideaway in a nearby forest.

Children in Baga, another community in Borno State, where the kidnapped girls lived, just after a Boko Haram attack one year ago.

News spread slowly amid conflicting reports from the Nigerian government. On April 16, a day after the kidnapping, the government announced that it had freed all but eight girls. The next day it retracted the statement.

Families and supporters of the kidnapped girls rally in Abuja on May 5.

Meanwhile, about 14 school girls had escaped captivity and returned home. The government said around 100 girls were still missing; residents countered it was more than 200. Rumors spread about the girls' safety and whereabouts.

For two weeks, angry Chibok residents demanded the Nigerian army help. Distraught parents set out to find the girls, still thought to be nearby. Boko Haram threatened to kill the girls if the parents did not stop their rescue attempts.

With the rallies, international interest in the kidnappings, and in Boko Haram, also rose. The Nigerian government defended its response. On May 4, Jonathan suggested that parents of the girls had not cooperated with authorities.

That same day, Jonathan's wife, Patience, publicly met with two of the leaders of the protest movement to find the girls — and then privately arrested one. Officials first claimed the activist misrepresented herself, and then denied the arrest.

On Monday, a video was released in which Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau admitted that the group had kidnapped the girls and threatened to sell them as brides. He also vowed to fight democracy, Christians, Western education, and constitutionalism.

View this video on YouTube

"There is no president in Nigeria. No president in Nigeria, no president in the world only Islam," Shekau said in Boko Haram's latest video. "This is a war against Christians and democracy and their constitution, Allah says we should finish them when we get them."

International condemnation increased as #BringBackOurGirls continued to trend. On Tuesday, Al Azhar University, a center of Sunni teachings, called on Boko Haram to release the girls. The same day, the U.S. offered Nigeria "counter-terrorism assistance."

Now, both the U.S. and U.K. will send teams to advise on intelligence and negotiations. Nigeria was initially reluctant to accept the U.S. offer, in part because the U.S. has been critical of Nigeria's tactics for battling Boko Haram before.

On May 7, Nigerian police reported that 125 people had been killed in another Boko Haram attack in the north. The news reinforced fears that there is no easy fix to Boko Haram's battle with Nigeria's political establishment, in which the kidnapped girls, left unprotected by the state, have become but another pawn to play.