The sun has set on the first warm Saturday in May, and Nancy, 29, is sitting up against a wall on Cornmarket Street in Oxford's city centre, trying to shake the evening chill and collect a few pounds from her sketches. Pedestrians stream past as she concentrates on her latest drawing: Elsa from Frozen and the words "Let It Go".

Nancy (pictured above) is petite, with facial piercings, a rugged stare, and a deep laugh that comes with disarming ease. At the age of 14, she left home. "I never really got along with my family from, like, a really young age," she tells BuzzFeed News. For the next four years she coach-surfed and used traveller sites and squats. Drug use, depression, and abusive relationships became part of the blur.

And then, one day, she didn't have anywhere to go. She was working at a bar and had left her abusive, "sexist and unpleasant" boyfriend. Her boss said she couldn't stay in the bar's empty room. And that was that.

"Because of my teen experience, I thought I understood what it was like to be homeless, but it's a whole complete different thing," she says of her seven years on the streets.

For a time, Nancy lived in a pitched tent alongside the River Thames. Now she makes use of the city's shelters, which charge from £3.50 a night to around £30 a week. Drinking and drug use among many residents are rife. "When you're in the hostel, you get used to people just dying all the time," she says. And they are young people. They are not old. And nobody cares."

Among Oxford's homeless, Nancy considers herself one of the luckier ones. "I have goals, I have dreams, and that keeps me going," she says. She is passionate about her art and can debate the ins and outs of UK politics. "Others in the situation I am in are completely lost."

And for many of them, things could be about to get a whole lot worse. Under the 1824 Anti-Vagrancy Act, persistent begging is illegal in Oxford's city centre. Police can already fine or arrest violators, or issue 48-hour bans. On Thursday, the city council was due to vote on a Public Spaces Protection Order (PSPO) to increase its powers to ban individuals for "antisocial behaviour" in the city centre or fine them a fixed £100. The PSPO is basically a ban on certain acts in a particular public space – and this one covers acts like persistent begging and unlicensed busking that are part of many homeless lifestyles. Even dogs without leads can now be criminalised. The PSPO also gives more powers to the council to hire its own enforcers to issue bans, bypassing the police. The vote has now been deferred after legal threats from the human rights group Liberty.

Supporters of this PSPO, and others like it, say it's needed to discourage more homeless from coming to Oxford and encourage the use of current programmes. Critics counter that it further marginalises the already marginalised — and makes no financial sense to fine the already homeless. In May, after a change.org petition gathered more than 70,000 signatures, the council removed rough sleeping (as well as pigeon-feeding) from its proposed list of infringements.

Oxford is now the UK's least affordable city to live in. Over 6,000 people are on the waiting list for affordable housing – but virtually no new council housing is being built. That means that housing benefits can't get you close to a house in Oxford these days – and, in turn, that there has been an increase in the number of people homeless, or teetering on the edge.

The exact number is difficult to determine; according to the council, 43 people were sleeping on the streets in March, the Oxford Times reported. But that doesn't include the 200 or so people staying in shelters each night, and hundreds more living in tents or couch-surfing on the brink, as Nancy did.

Compared to other cities worldwide, these numbers are small. But in the UK context, homeless organisations warn, they're significant. Oxford city council spends over £1 million annually on homeless services, and more than 10 organisations cater to the homeless, including night shelters, hostels, a medical fund, and supported accommodations. These services have a reputation as being among the better ones in the UK. Yet in January, the county council, facing budget cuts, slashed funding for homeless services by 38%.

Like anything British, there's a hefty set of bureaucracy that goes into seeking help as a homeless person. To make use of Oxford's shelters at night, for example, you must be on housing benefits and prove a local connection, such as family, a previous residence, or work. If you don't, and the city finds you sleeping rough, you can be sent somewhere else. Reduced funding means the organisations and people that support them will have to find even more ways to cut corners and stay afloat.

"Between the police, the local council, and the government, they are putting cuts to all the benefits, they are putting cuts to all the services, so all the most vulnerable people are going to get the worst," says Nancy. "You can't just try and sweep people out the carpet or try and push people out of the city and think that maybe in another city they won't be your problem."

But at times Oxford seems to be trying its best. Nancy can't sell artwork in the city centre because she doesn't have one of several permits to vend, which also cost money and require "good character" and other restrictions, according to a council spokesperson. (Nancy instead takes donations.) Oxford's job market is tough – and for the homeless or formerly homeless, many with police records or no mailing address, can be near impossible.

"Even people who go to Oxford University will still find that they are struggling to find a job," Nancy says. "So what hope does somebody who doesn't have those kinds of qualifications got?"

Nearly 1 in 10 adults in the UK have been homeless at some point, a 2013 study found. In Oxford, stories circulate of attacks on homeless people by students – like beer bottles being thrown or students peeing on them. Nancy rolls her eyes over the boys who catcall her at night.

It's the stigma of being homeless that often hits hardest, she says. "Anyone who is homeless is going to have some kind of mental health problems, whether it's just low-level depression because of how they've ended up in this situation," she says. "The one thing that I hate the most is when people say that it's a choice. Because it's really not a choice. You fall into it. And it's so hard to like crawl your way back out again. And people manage to do it. But the majority of people don't. The majority of people end up dying, either through like illness or addiction and overdosing, or health problems."

For Oxford's homeless, the situation is complicated by the role of the institution that dominates the city – Oxford University. Most of the 11,000 undergraduates live in accommodation owned and subsidised by the 38 colleges, which also take up of much of the prime downtown housing real estate. Many of the 10,000 graduate students rent apartments in other areas of the city, driving up rents.

Some students and residents have discussed whether the university – with its £2 billion in investment assets – should do more to address the worsening problems within the city it physically and financially dominates.

"You are all smart," Lesley Dewhurst, who works with Oxford's homeless, told a May panel discussion on housing and homeless issues. "Perhaps in the future you could be able to do something about it."

Paul Roberts of Aspire, a local organisation that helps find the homeless jobs, has an idea for what more should be done. He thinks Oxford colleges should sign on to the Living Wage Campaign, which requires employees pay at least £7.65 an hour (only five have completely done so), and should consider investing in more social housing.

Roberts puts it bluntly: "If your college is not using the wealth, the land, the endowment that they've been blessed with to help solve this, then they are contributing to the problem."

"The university is extremely wealthy," says Yyanis Johnson-Liambias, a 20-year-old student from Birkenhead and part of the student-run Turl Street Homeless Action programme. "They have the means to help and that they don't gives the impression, rightly or wrongly, that they don't care."

Freya Turner, 20, a history major from London, found the university largely unresponsive when her student group, On Your Doorstep, started to organise against the initial inclusion of rough sleeping in the PSPO. They tried to find what land the university owns and how it is being used, but found getting further details out of the colleges other than what is already online a frustrating process.

Instead, it is left to individual students to help out. On a chilly evening in early May a dozen undergraduates gathered at a student house and packed up hot water, tea, mini chocolate doughnuts, and cheese and ham sandwiches. They were part of Just Love, a Christian social justice group that organises twice-weekly homeless outreach via Facebook. Before the group set out, they closed their eyes and prayed.

The Just Love students know by name nearly all of the people homeless and begging in Oxford's city centre. They don't give money directly to the homeless – something most organisations discourage – but will buy small items for them, such as dog food for pets. The group's meals receive mixed responses. "Nothing warm? Everyone gives us sandwiches," one homeless man complained one night. But anything with chocolate in it is always a hit.

For Joshua Parikh, 18, from London, it's the human contact with the homeless people he talks to that he finds most important. It's almost like watching a parent talk with their college kid: "What did you do today? Have you slept and ate? Anything small I can help with?"

For the university, however, the priority for students should be completing their coursework: Volunteering, Parikh says, is not something that's really encouraged. Help for the homeless, students often say, is important – but not at the expense of their work.

Still, Turner was pleasantly surprised when pro vice-chancellor William James agreed to be on a panel on the housing crisis in May. It was, she says, the first time in months of organising that the university had joined the discussion.

A spokesperson for James told BuzzFeed News by email that the university is "very conscious of the extra tension housing the staff and students puts on the City's housing stock, and are doing everything we can to relieve this". It plans to build a new graduate housing complex to meet growing needs, he told the panel. (Oxford is surrounded by a green belt, making it forbidden to build in certain areas.)

However, the spokesperson refused to comment on the PSPO, saying: "This is very much a matter for the City Council. They have the difficult responsibility of ensuring a safe and manageable environment for all the community of Oxford, and often have to balance the needs of one group against another. It would be wrong for an organisation like the university to cherry-pick items of their policy for isolated criticism or comment."

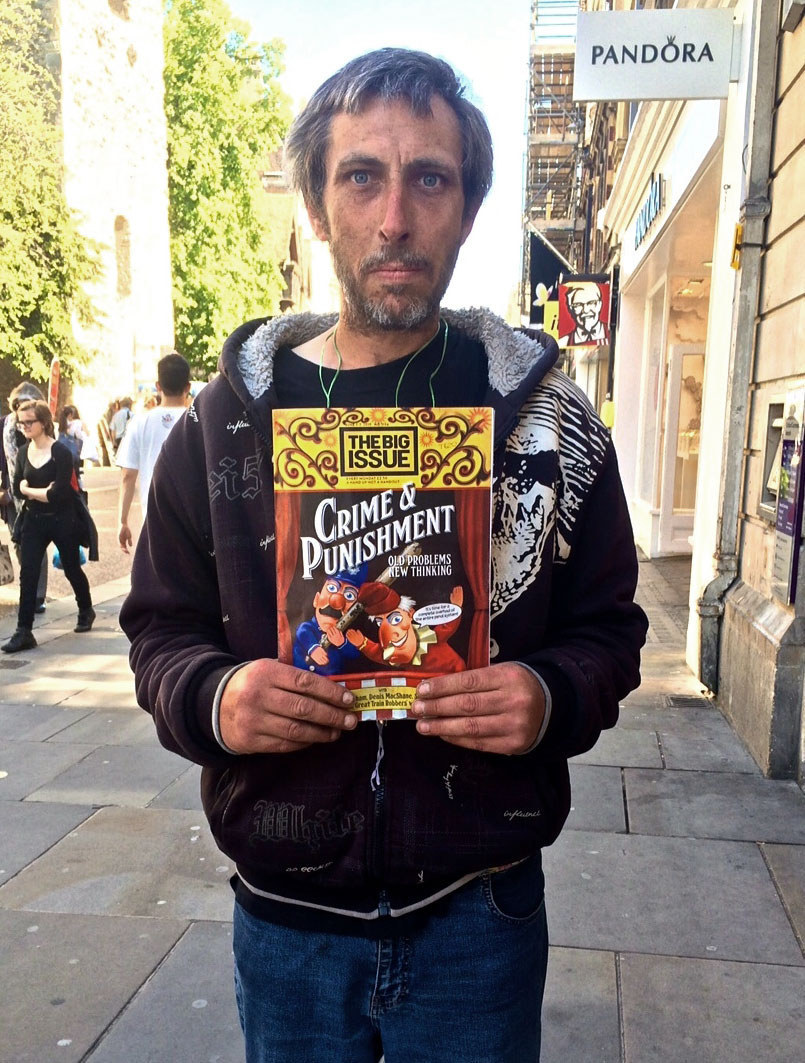

That won't be much consolation to someone like Sticks, 49 (pictured above). A short man with piercing blue eyes and a weathered face, he is one of Oxford's unseen. "It all looks nice," he says, his voice low and slow, his thoughts at times disjointed. "But it's not."

Twelve years ago, Sticks said, he built his own house by hand. Then things spiralled out of control: first the divorce, then a series of sickness, and suddenly a life he didn't want to live, dictated by bouts of depression, drugs, and nights on Oxford's streets.

Sticks (his local nickname after years on crutches) has the look of a man in the ruts. His hands are dirt-stained, his clothes a hodgepodge of flannels, and his teeth only half there. But he's also found ways to keep his individuality. He downs chocolate like there's no tomorrow and insists he won't take anything with mayonnaise, even when starving.

Sticks has watched Oxford's commercial area and walled-off colleges build up over the years. He's also watched the rise of new drugs such as spice ravage an already-ravaged community. He recently moved off the streets and into a house subsidised by a local church.

Sticks says he doesn't beg any more. But sometimes, when he feels the need, he still sits on the street with his round cap out, his legs crossed, and his head low.

As for Nancy, the council's proposed crackdown is the latest of the stresses on her these days. "I think most people would think, 'Oh, great, at least it's less of a strain on the NHS and our tax money isn't going to be spending more money on this,'" she says. "But they [homeless people] are all people. They all have reasons why they ended up homeless. And some of the stories that I've heard from people about how they've ended up on the street: If anybody heard those stories and was still cold towards them, then I wouldn't be able to understand that person at all. I'd think that, like, don't you have a heart and a mind?"

This piece was updated to reflect the fact that the vote on the PSPO has now been deferred.