When I guessed correctly that it was my brother, Julian, coming through, the licorice- colored coffee table rocked back and forth a couple of times before tipping, my knees catching the thing before it could fall to the ground.

“It’s him,” said Janice.

The heavy table pressed into me, hard. “He’s giving you a hug,” Janice continued, exhaling with steady assurance even though my brother Jules had been dead coming on twenty years.

Outside the cottage of Janice Nelson-Kroesser, chocolate-milk mud puddles booby- trapped the path to her front door. A thin April fog hovered several inches over the slushy gravel driveway, ambivalent, like a shy snake. Beyond Janice’s parked minivan, a gaggle of boarded-up cabins lined Pond Street: cold, dark, cockamamie and hibernating cottages, waiting for their summer residents to wake them up come May, to have life zapped back into their old, dead gingerbread-house bones. Behind them, the air sap-filled and sweet, a tall forest of pines with creeping bittersweet, chopped logs, and brush, make way for a little clearing in which sat port-a- potty with a laminated note taped onto its door: BE AWARE! TOADS HANG OUT ON THE TOILET TISSUE ROLL.

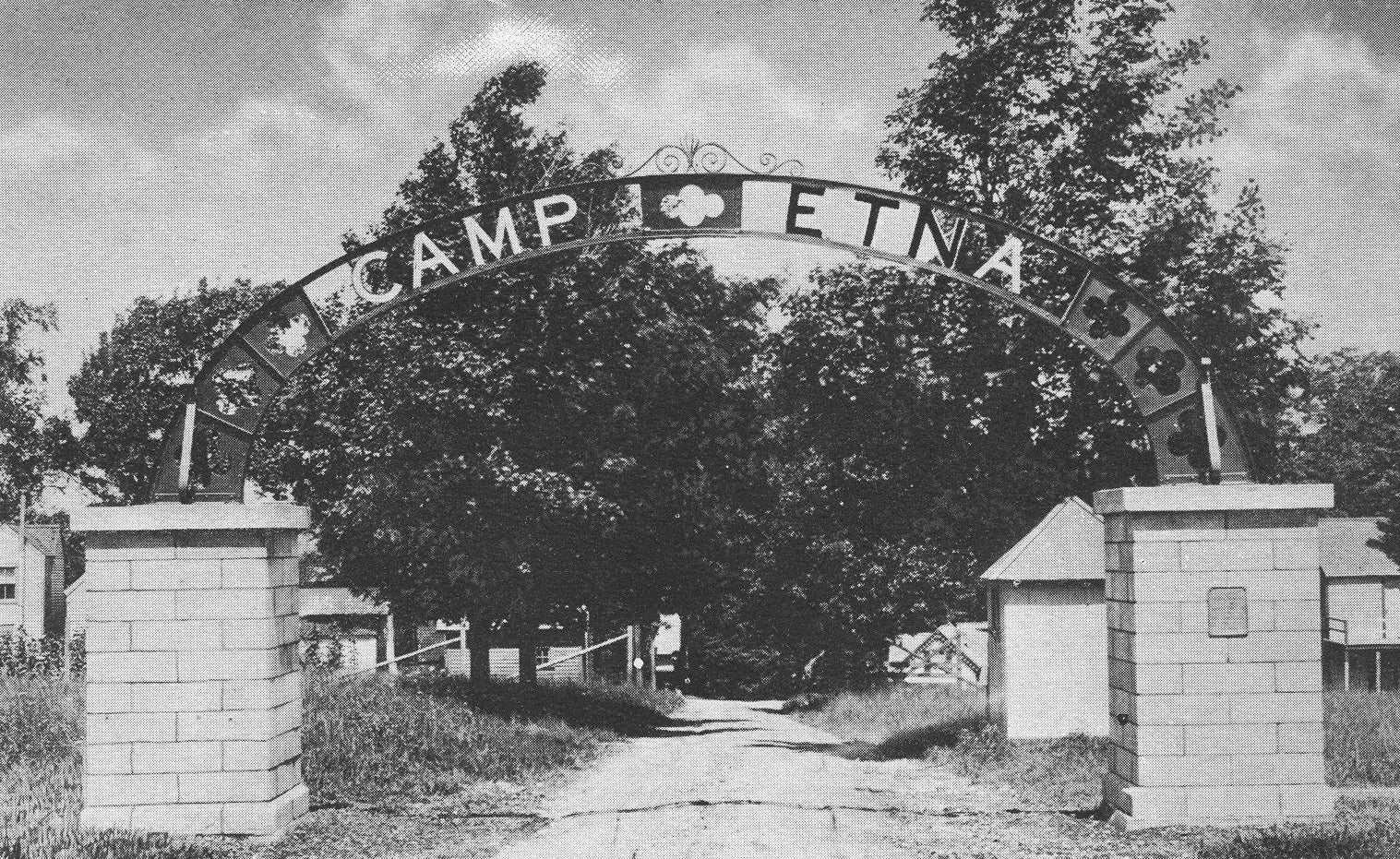

It was spring in Maine and we were at Camp Etna, the 141-year-old Spiritualist community brought to life in 1876 and, compared to its explosive popularity back in its youth and teenage years, kept pretty much secret for the past fifty. It was a hard place to find, and if it hadn’t been for a friend, Celia, mentioning it to me, I probably never would have really known that Spiritualism was an actual religion, nor would I have ever found this sleepy hollow. I was 34 years old, living in Maine, and until this year I had never heard of Camp Etna. Despite its Burning Man–sized popularity back in the 19th and 20th century, most people I spoke to knew zilch about this place either. When I asked the gas-station clerk a quarter mile down the road from Camp Etna if she had any idea of what happens up the street behind the rusty iron gates at 77 Stage Road, she handed me my change and my bag of Cheetos, looked at me blankly, and supposed that the place was just a summer camp for Cub Scouts. She wasn’t entirely off in her guess — the enchanted hamlet did build lots of bonfires, and the place was for scouts, it’s just that Spiritualists were the kind of scouts who ventured into the afterlife rather than into national parks. They spoke to the dead rather than earn merit nature badges, so that’s what I told her: that Camp Etna is a magical living organism of a community for clairvoyants, for mediums, for psychics, flute-playing shamans, table tippers, trance channelers, mind-readers, dousers, Reiki healers, angel painters, past-life readers, hypnotists, paranormal investigators, and other like-minded Spiritualists.

By Spiritualist, I don’t mean “spiritual,” as in, I’m not religious, I’m spiritual or I’m trying to meditate more, eat more vegetables, and be more spiritual. No. Camp Etna is legitimately a religious camp, and Spiritualism (with a capital S) is a legitimate, organized, officially recognized, tax-exempt religion. Unlike most religions, Spiritualism is fairly young. Like most religions, Spiritualism was founded by humans who believe in a higher power and life after death, as well as living life with purpose, and have dedicated that purpose to their religious pursuit. But what makes Spiritualists different from the most popular American religions (a poll by the Public Religion Research Institute estimated that 69 percent of the Americans are Christians, 45 percent professing attendance at a variety of churches that could be considered Protestant, and 20 percent professing Catholic beliefs) was that Spiritualists believe each and every living human has the power and was born with the tools to access and communicate with that great unknown directly, as well as talk directly to people who have passed and gone back to the big white light. In other words, Spiritualists have two major beliefs in their faith: that it is our duty to practice the Golden Rule, and also that we humans can talk to the dead if we want to.

Spiritualists believe that the human spirit is with us always, even after people die, and that we have the tools to reach these spirits.

They trust that ghosts are not facile, are not hoaxes, and are much more than white sheets with eyeholes cut out. Spiritualists believe that the human spirit is with us always, even after people die, and that we have the tools to reach these spirits. They believe that somewhere within our flesh, our eyeballs, our brain, our muscle, fingernails, bone marrow, hair, and heart is an organic phone line from which we can chat with God, access angels, and converse with the dead if we want to. Spiritualists are also willing to offer and provide scientific evidence to prove what many people may otherwise believe to be a bunch of bullshit. And as for the rest of us? Some people believe them, and in them. Many are on the fence.

Others laugh in the face of the Spiritualist belief system. Regardless of what the outside world thinks of it, at Camp Etna, the religion lives on. Since its birth in the late 1800s, Camp Etna, the tiny rugged hamlet in the middle of rural Maine, has served as a sacred meeting ground for the mystical evolution of many of these Spiritualists—a place for them to meet regularly to sharpen their swords, learn new skills, talk to the dead, heal others by accessing the great beyond, tighten their worldwide community, and eat some really good homemade pie and pot roast. Despite efforts to shut the religion down and shut the women up, to shove them into the corner under the label “hysteria,” despite all this, a century and a half after its conception, the camp still remained a living and breathing community. Today, as summer neared, Camp Etna was yawning and stretching, once again about to open its gates for peak Spiritualist season.

The inside of Janice’s cottage was and calm and smelled like roasted vegetables and melon-scented candles. This was their summer place; Janice and her husband, Ken, called it Phoenix Rising, and small wooden signs with words like “Laugh” and “Love” and “Welcome” hung on the walls, the font painted in curled, feminine letters. Believe in Magic. Welcome to the Funny Farm. On the kitchen counter: Dr. Bronner’s lavender soap. Chia seeds. Fresh sunflowers in a vase. It was a pleasant place. A lit brass lamp rescued from one of the abandoned Etna cottages made the small, warm room dim and intimate. Actually, sitting there in chairs with Janice felt like we were in a funeral-home parlor, which, in a way, we were, because we were about to visit with the dead: a séance was about to commence. Specifically, we’d be having a certain type of séance called “table tipping.”

The route from my home to Camp Etna is two hours on the dot. I live on a tiny island just off the coast of Portland, Maine. After kissing my children and husband goodbye this morning, I took a twenty-minute ferry ride, got in my car, and took to I-295 north. Pine tree, birch tree, hemlock, pine. The farther north I drove, aside from the handful of Subarus that passed me on the road, there was no indication of what era or decade I was in; years ago, Maine outlawed billboard advertisements on all of her highways, making the highways pleasant, timeless, and meditative.

Pine tree, birch tree, hemlock, pine. Public radio was playing a podcast called “Clever Bots,” in which the hosts explored ways in which computers and technology were reshaping our ideas of what it meant to be human: nowadays, even a most basic computer chat program could mimic human emotion and intelligence. As I pulled off the highway into the teeny town of East Newport, the host spoke of a man who had inadvertently fallen in love with a chatbot on an online dating site. The host then recounted the true story of a man who coded “Cleverbot,” a sentient software program that goes by the name of Al that learns from people, in context, and imitates them. Al the robot had figured out how to have empathetic conversations with humans and had been acting as a bit of a therapist to more than 3 million humans each month. Finally, as I pulled into Janice’s driveway at 16 Sunset Acres, and right before I shut off the engine and walked up the steps to meet my medium, alive and in the flesh, the radio host posed two questions to the listeners: (1) was it actually possible for machines to think and feel? and (2) if they could, how could we humans ever prove it?

“The table is very old, so it has lot of energy in it,” said Janice as I placed my nervous fingers on the table. I tried to remember to relax my body, as she’d instructed me. Table tipping, she explained, was a type of spirit communication in which we, women, people, the bereaved, whomever—whether it be one to twenty-one humans—would sit around a table, place our hands on it, breathe, relax, believe, and wait for movement from the table. The table might rock. It might rotate. It might spin, it might elevate. Before it happened, you wouldn’t know what to expect other than that the table’s movement would be coming from the dead. Through the table was how they would talk. Table tipping was Janice’s specialty. In the Spiritualist community, it was what she was known for. I was new to it. In fact, I was completely new to all of this.

Music wafted throughout the cabin. Gentle, New Age and techno-ish, like a funkier version of Kenny G.’s “Sax by the Fire,” but still soft. Music with no words; the kind you’d hear in the lobby of a recently renovated hotel, updated and an inch closer to smooth. “The table goes where it wants to go,” she said, and although I didn’t understand, I nodded. The table itself was about three feet tall and two feet wide, maybe a foot and a half. Hard, heavy, wooden, vintage.

“I found this table at Elmer’s Barn of Junk and Dead Things,” Janice explained, “in Cooper’s Mills, Maine. She was in bad shape. But she had character. The top was all loose and she had square nails and pegs in her.” Janice rubbed the surface of the table. “But I took her home anyway, and asked Ken to fix her up, so, voilà!”

Table tipping, she explained, was a type of spirit communication in which we, the bereaved—would sit around a table, place our hands on it, breathe, relax, believe, and wait for movement from the table.

“Is this going to be like a Ouija board?” I asked. “But with a table instead? Exactly how big of a movement is actually going to be going on here?” Janice had soft, feathered red hair that smelled like it had just been shampooed. A dab of makeup here and there with just a bit of shimmer to it, a spritz of perfume. Janice was vampy. She was voluptuous, feminine; her form was like the human embodiment of a hug—a cherubic face, apple cheeks, doe eyelashes, and a bosom that made you want to rest your head in it while she raked back the hairs on your scalp with her precise red fingernails. Bangled wrists. Hoop earrings. Self-aware and self-nurturing; a woman. A Gerry Goffin/Aretha Franklin/Carole King “You-make-me-feel-like-a-natural-woman” kind of woman. She was rather gamey, and she was rather attractive.

“I’d tried them all,” Janice sighed. “Pentecostal, Catholic, Methodist, Episcopalian.

Nothing resonated with me.”

The electric fireplace popped on and off and on again, making me jerk my head around as if it were a sign, as if I’d got lucky on my first day in the field and spotted a ghost, but my hostess didn’t flinch.

She continued, “I got kicked out of Sunday school at the Baptist church for arguing with the Sunday school teacher because she said animals didn’t have souls, but I knew they have souls because I could see them. I can see dead people, and I can also see dead cats.” I looked down from my notebook onto the floor, thinking I might see a ghost cat in the room too.

“When we’re born,” said Janice, “we’re connected to Spirit, right? I mean, that’s where we come from, and when we’re young, well, children have that psychic ability. Imaginary friends? They aren’t imaginary. And then we socialize it out of them, and then they—we—stop exercising that muscle, and it just goes meeeeeerp. When I was a kid, I would tell my dad what I could see and he’d say, ‘No, no you didn’t. You didn’t see anything, shut up, you’re nothing but a witch.’”

Outside, a tractor stuttered then came to life. It was Ken, Janice’s husband. He was sharply handsome, like a game-show host, much taller than Janice. Fit, masculine.

“What does spiritual mean to you, Janice?” I asked, focusing myself back to the conversation.

“To be connected to a higher power,” she answered.

Another loud pop and a bang, and Janice rolled her eyes and grinned, motioning to the kitchen window. Outside, Ken was sitting on top of the tractor, jerking it out of a big mud hole.

“He’s doing one of his man projects,” she said. “Building a new shed. When we’re at Etna, he does his thing and I do mine, and it works.” Ken was Janice’s second husband; her first was abusive. “Those scars don’t show,” she’d laid out. “I went from a father who was physically abusive then I married a man who was verbally abusive, and I thought that’s just what things were like. That’s just what men were like.” Eventually, after her kids were grown, Janice left her husband—she said she was evolving and he wasn’t—then met Ken through a friend, and around this time in her life she’d begun attending a Spiritualist church, and that’s when everything clicked. “Until then, I was a closet medium. And when I found Spiritualism, I found Ken, I found my people, I found my religion, and I was released.”

In the coming months at Camp Etna, I’d learn what she meant. Soon I’d learn about what Spiritualism provided for its followers and practitioners since its conception, as well as what it provided for those who were just curious about it, those who had twenty bucks and a wild idea to go see a medium or psychic. I’d engage in the practices, go on a ghost hunt, release trapped spirits, access my Akashic records. I’d water witch. I’d read some auras. I’d be introduced to the metaphysical explanations and the science and the realms of our souls, the difference between an angel and a spirit guide (and how to get them to find you a parking space, and fast—it’s been working for me without fail ever since). But on this first day, the spring afternoon of table tipping at Janice’s, I knew nothing about Spiritualism’s past or present, or of its value and the empty space within death culture and grief that it filled, nor was I concerned about its future. I was a complete neophyte, just a journalist eager to see a ghost, and so in the beginning and for a good bit of my time at camp, I’d cling to my superficial knowledge about those who believed in and coexisted with what they believed to be the supernatural. But before all this, our hands were on the table.

“You know,” said Janice, “I’d like to think I just stumbled upon all of this, but I also think my spirit guides were responsible for it too. They brought me where I am today. We all have them.”

I smiled at Janice then squinted, trying to see or feel a glimpse of something—smoke or vapor or a shadow or anything that could be an extra presence. I was trying to locate my own spirit guide. Nothing came of it, or at least nothing that I myself could see.

“You meet them through meditation,” said Janice. “We all can do it. I used to meditate every day before I met my husband. I found my best meditations were in the bathtubs. Candles around the tub, that kind of thing. And some kind of classy music is on and I just drift. And I’ve had some of my best, best, best communications that way.”

“Can you see my spirit guides?”

“I can’t,” admitted Janice. “I’m not that good. Some people will tell you, ‘Oh yeah, you have an Indian standing right there,’ but I’ve heard that medium describe it to ten other people that way. Those people aren’t mediums; they’re shysters.”

Janice scooted to the edge of her chair and lifted her spine, making herself more erect, and described one of her guides.

“Sam,” she said. “He has me call him Sam, but I think it was Samuel. He’s probably from the sixteenth century. He’s dressed in that kind of garb. Shows himself to me that way. He’s around me a lot. Not 24/7, but he could be if he wanted to.”

“What about during ‘intimate moments’?” I asked. “Like sex. Is Samuel around then or does he give you . . . privacy?”

Janice’s mouth made a curved line. “Actually, I had Spirit help me once. And there are spirits out there that do have sex with you, and that’s happened to me once. Just once, though. I was paralyzed when it happened. I couldn’t move. I wasn’t asleep but I was totally aware of what was happening.” The front door opened and in walked Ken. He stepped into the kitchen, paying us no mind, opened the fridge, bent over, stuck his head inside.

“I was single at the time,” said Janice, not lowering her voice. She looked over at Ken then back to me. “It was a weird sensation.”

“Myra?” Ken sang sweetly, mispronouncing my name. “Can I offer you some filtered water or organic tea?” I shook my head no and smiled then turned back to Janice.

“And that’s what happens,” said Janice. “We get so busy with our personal and work life that we don’t slow down and connect with Spirit.”

“When you die,” I asked, “what will you do with your body?”

“Probably cremation. I find this body so hard to maintain . . .” she trailed off, sighed, and looked down. This was followed by a tricky silence. “So,” said Janice, finally breaking the quiet. “Should we table tip or what?

Before coming to Camp Etna, I was not a true believer in anything. It’d be most accurate to say I’m riding the fence of faith, further away from being an atheist and closer to a “you never know” kind of a hope. I did not come to Camp Etna seeking out proof that life beyond death exists, nor to debunk some deception. I came to Camp Etna to learn about how a strong, independent, faith-based subculture of women (and a few men) live and have lived for centuries, unbeknownst to most of us, in a specific way that is exquisitely fulfilling to them.

One of the most absurd things about the human mind is that it can reason unreasonable things. Faith is unreasonable—that’s the nature of it: it’s unscientific, unprovable, and it relies on itself. It requires devotion. What makes Spiritualism different from many religions is that it believes it does have proof: the tipping of the tables, the messages from the dead.

“Please place your hands on the table,” said Janice. “First we will do a prayer.”

I bowed my head and closed my eyes but then peeked up at her.

“Infinite Intelligence,” she prayed, “we ask that you put your white light of protection around us. We ask that the highest and best come to us, we ask that angels, descending masters, guides, our families and our loved ones, that they come to us and help us to guide us throughout life as we walk down our path. Amen.” She opened her eyes and looked at me.

“Amen,” I agreed, and took a breath.

“Next, we are going to use our chakras,” said Janice. “You know about chakras, right?” I’d heard of them.

Janice began to explain, but the table had already started moving. It was moving hard.

I came to Camp Etna to learn about how a strong, independent, faith-based subculture of women (and a few men) live and have lived for centuries, unbeknownst to most of us, in a specific way that is exquisitely fulfilling to them.

And fast. She stood up, pushing her chair quickly out of the way. I stood up as well, trying to keep up with her, or the table. It was up and running without warning, immediately rocking around the room like a clodhopper, rotating on its four legs, tipping hard and so fast, but it stayed under Janice’s three or so fingers like a piano’s keyboard.

I basically galloped in order to keep up with Janice and the table as they spun into the next room. They were dancing together. Despite the fast movement of the furniture and my fumbling around to stay with them, it seemed to me that it was Janice who led the duet. The thing wasn’t floating on its own, because her fingers were on it the entire time, and that’s the only way I can explain it, because that’s the only thing I could make sense of, given the quickness of it all, and my befuddlement. Then, when we were closer to its original position in the living room, the table stayed in one location but began rocking faster and harder, my hands slipping off the table again and again, all the while Janice with her hands on it, then just one hand, then both again, then just a couple of fingers, her face smiling calmly down at the table and then at me, cool as a cucumber. It rocked and rocked smaller and smaller as Janice lifted all her fingers but one—her pretty painted index finger, now right smack down in front of her on the table pressing down, as if she were pushing down on a child’s forehead.

Finally, the rocking slowed, the table rocked to the left then to the right then stopped into the position a table should be in. A two- or three-second pause, and then it tipped once more to the right, leaving us unsure what it would do next. Janice laughed at it a little, lovingly and permissibly at its minor rebellion.

“So basically,” said Janice, “now we are gonna just sit here with our hands slightly on the table.”

I put my hands back on, hesitantly, as if the thing could possibly bite.

“And you say, ‘is there anybody here for—and then you put your name out, because it gives off your vibration.”

I did as I was told. “Is there anybody here for Mira?” I asked.

The table rocked to the right.

“Yes,” said Janice. “Right off. It rocked to the right. Yes is to the right. Is there anyone you think it might be? She’ll tip to the right now if it’s a ‘yes,’” said Janice.

I had known people who had died, just as much as anyone else did. The closest to me had been my younger brother. I asked, “Is it anybody I’ve lost, like a relative? Like, maybe direct family member?”

The table rocked right. “Yes.” “Could it be . . . is it a boy?”

It rocked to the right again. “Yes,” said Janice. “Oh, OK. Well, then could it be Julian?”

And that’s when the big heavy black table leaned forward, pressing itself into me and Janice smiled.

“A hug, she said. “He’s giving you a hug. Now. Close your eyes, feel the energy. He’s hugging you so tight. Can you feel it?”

I closed my eyes. I told myself to think of my brother. I tried to feel him. I saw the memory of his face in my head, a memory I hadn’t intentionally dedicated a moment to open up at and explore consciously for more than a minute in quite a while. Julian had died in 1997, at age fourteen, after he was hit by a drunk driver. I was seventeen at the time. After he died, I had trouble remembering anything about him, as if the trauma had shut down a certain part of my brain where the memory of Jules lived. But during this moment, I did feel what it felt like when I thought of him, or what it was like to be around him, or what he felt like. The moment was fleeting, because the voice in my head returned to the queerness of the situation. I opened my eyes.

“What do you want to ask him?” Janice asked. “Remember, it can only be a yes-or-no question,” she said. “Back in the olden days, table tippers would use the alphabet, but it ended up taking too darn long to spell out the answers. So now we just use the yes-or-no questions.

A hug. Your brother is giving you a hug. It was a euphony I wanted to hear, regardless of the context. Under pressure, I had no questions for my dead brother. Or maybe I was just too confused in the spur of the moment, so Janice suggested some questions. She went ahead and asked the table. They told me he didn’t suffer when he died. That his death was planned, it was all part of life’s plan, and that he was happy. I was told that I wouldn’t have any more children, and that I needed more strict boundaries for my son and daughter, and that both my father and I needed to take more time to talk to Jules. These words were given to me, followed by the sound of Janice’s breathing, and then, in somewhat stunned reflection, I said clumsily, as if ending an awkward job interview, “Okay, then. I guess those are all the questions that I have!” and took my hands off the table.

“Wait,” said Janice, still calm and somewhat trancelike. “Before we close up the session, I myself want to ask a couple of questions.” Janice closed her eyes, inhaled, exhaled. “The two ladies I just hired. Will they be good employees?”

The table rocked right.

“I had that good feeling in my gut,” said Janice, “and I just wanted to confirm. And am I going to find someone to buy my facility?” She opened her eyes and turned to me as an aside, and said, “It’s a nonprofit, and I don’t know how to back out of it. It’s hard to sell and I’m hoping to retire, find someone to take over and give me a nice severance package, just enough to live on . . .also, is this Sam?”

Yes, the table tipped.

“Okay, good,” said Janice. She paused another beat, inhaled and exhaled again, and said, “And now it’s time to close the session. Thank you so much for coming and doing your best, spending your time and energy so that we could communicate with our loved ones and be in a safe environment, protected and loved. Thank you so much for that.”

“Hallelujah. Can I say that?” I asked. “Amen?” “Amen.”

We closed the session, chatted a little longer, just the two of us, and Janice invited me to the upcoming Camp Etna board meeting. Janice walked me to the door and Ken to my car and waved goodbye.

After leaving the gates of Camp Etna that first day, I swung by Country Corner Variety for some soda water and homemade fudge, packed myself back into the car, and hit the highway back to the land of the living. I drove in silence the whole way, concentrating on thoughts and memories of my brother, which was something I hadn’t done in a long time, and thinking about the radio hosts’ questions about things that were not alive. Was it actually possible for them to think and feel and communicate with the living? If they could, how could we ever prove it?

Soon I would arrive home and jump back into my fast-moving, modern life. And soon, I would pick dates on my calendar to return to Etna. The snow would melt, spring would pass and the warmth would arrive, and Camp Etna’s Reverend Gladys Laliberte Temple, the cobalt- colored Healing House, and the Ladies’ Auxiliary would be up and running. Someone would flick on the lights to the Camp Etna Museum, with all its artifacts unsorted but saved, kept secure in plastic bags. A key would be inserted to unlock the doors of the Rotary Room and the Visiting Mediums’ Cottage, the Hot Spot Café, the kitchen and chow hall. Soon, the enigmatic mediums would breathe life back into the summer cottages, pull up their shades, dust off their steps, and hang their tin shingles. As the summer seekers arrived, the Spiritualists of Camp Etna would rock and rock and rock on their porch chairs, and, once again, their story would begin. ●

From the forthcoming book The In-Betweens: The Spiritualists, Mediums, and Legends of Camp Etna. Copyright ©2019 by Mira Ptacin

Mira Ptacin is the author of the award-winning memoir Poor Your Soul (Soho Press, 2016) and the forthcoming book The In-Betweens: The Spiritualists, Mediums, and Legends of Camp Etna (Liveright, October 29, 2019) She leads memoir workshops for incarcerated women and lives with her family on Peaks Island, Maine. www.miraMPtacin.com