It was after 2 a.m. on March 25, 1993, when Barbara Paris heard footsteps coming from the back of her South Side Chicago apartment on South Albany Street. A moment later, she smelled gasoline. Paris asked her husband, who, like Barbara, is legally blind, to investigate. When he got to the door, he called to his wife, “The door is hot, the house is on fire. Let’s get out.”

The couple’s 14-year-old daughter, Kasey, led her father out the front door. Their older son, Scott, was not home. Barbara stayed behind to alert the elderly upstairs neighbors, Peter McGinnis and Margaret Mesa. She shouted into the phone, “Get out! The house is on fire!” over the shrill of glass shattering and wood collapsing. Mesa, who was hard of hearing, couldn’t understand her.

Bright flames made the whole place look like daylight to Barbara, despite the fact that she could barely see. She pleaded with Mesa as she felt the fire getting closer. Forced to drop the phone and flee, she raced outside and heard Mesa and McGinnis cry out from the second-floor windows: “Help us, please!”

When they got to the second floor, rescue team members stumbled over Mesa's and McGinnis’s bodies in the bedroom. They were pronounced dead about an hour later at the hospital.

Mesa's and McGinnis’s deaths in the spring of 1993 came at a particularly volatile period for the city of Chicago. In 1993, the total number of violent and property crimes, like arson, peaked, according to statistics supplied by the city’s police department to the FBI. The South Albany Street fire joined this list. The case was ruled an arson, and therefore, the two deaths were classified as homicides.

Three years later, when that suspect was convicted of double-murder and arson, the families affected by the tragedy thought justice had been done.

The investigation progressed quickly. Within hours of the fire, the key evidence was gathered. That same day a suspect was arrested, interrogated, and, after he confessed, charged. Three years later, when that suspect was convicted of double-murder and arson, the families affected by the tragedy thought justice had been done.

However, 23 years later, advances in fire science evidence have led many — including the Cook County Circuit Court — to question whether the investigators made the right call about what really happened on the night of March 25, 1993. And this June, a man who has spent most of his life in prison may get a chance to prove his innocence.

Out in the street that night, a crowd had grown. Scott raced home from a nearby bar to find his sister and parents outside; they did not think this fire was an accident. In fact, the Paris family already had a suspect in mind: Kasey’s ex-boyfriend Adam, who she said had made threats against her since she started dating his best friend, Mel Gonzales.

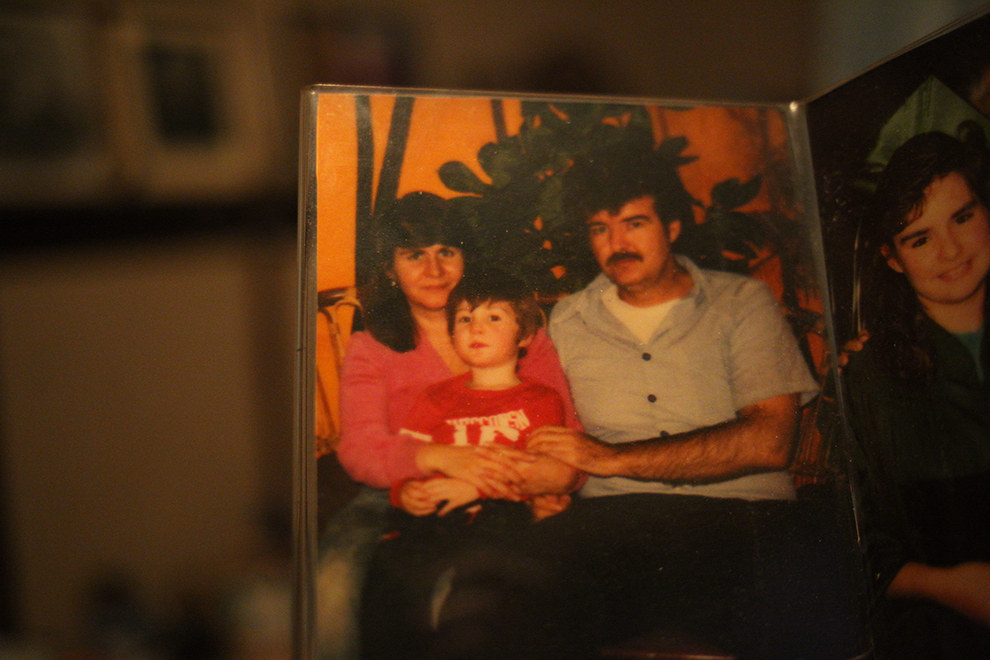

Fourteen-year-old Adam Gray and his mother, Gertraud, lived across the street. As the fire raged, Gertraud was awakened by the thick smell of smoke and the commotion outside. When she came outside, Scott immediately confronted her.

“I hope to fucking god Adam didn't do this,” Scott sneered.

Fire investigator Joe Gruszka arrived at the fire at 3:20 a.m., shortly after it had been put out. The Chicago Fire Department would have been hard-pressed to assign somebody with a better résumé to this fire than Gruszka. A 20-plus-year veteran, he had spent half his career in the department’s Office of Fire Investigation. He was certified in arson investigation by the state’s fire marshal office. He was also member of the International Association of Arson Investigators. Gruszka had been to over 20,000 fires in his career, and worked to determine the cause and origin of about 5,000.

When he got to the back of the house, Gruszka observed that the fire had totally consumed the wooden stairs that led up to the Paris family’s apartment. All that was left were charred remains.

When Gruszka inspected the blackened debris, he observed “alligatoring” in the wood — shiny, raised blisters that gave the wood the appearance of a scaly alligator back. In the world of arson investigation, the presence of “alligator char” was commonly believed to indicate an accelerant had been used.

Gruszka went to his car and retrieved his hydrocarbon detector — a device, he would later testify in court, that when applied to an area where an accelerant is present “will just start buzzing like crazy.” When he held it to the stairs, he said he got a “very strong response.”

Gruszka had also inspected the fuse boxes and some exposed wiring in the house. He saw nothing that suggested this had been an electrical fire.

Chicago Police also sent its arson unit to investigate. Detective Ernie Rokosik, a 20-year veteran on the force with more than 10 years in the unit and 2,000 fires under his belt, arrived at the scene about 4:15 a.m.

One of the observations Rokosik made was heavy charring at the ground level of the stairway, commonly thought to be an indicator that an accelerant had been applied to the floor. (The logic is that that fire travels upward, so in any common fire the heat and flames would rise and the floor would be spared.) Rokosik’s team took two debris samples — one from the base of the staircase, and one from the rear door of the first-floor apartment — to be transported to the crime lab.

All the evidence was coalescing into a case. Rokosik and Gruszka were pretty certain that an arsonist had doused the stairs leading up to the Parises' apartment with accelerant and then lit the blaze.

Thanks to Kasey Paris, who had spilled the details of her ill-fated teenage romance with Adam Gray, the police also had a lead on a possible suspect.

Twenty-three years later, Adam Gray’s memory of March 25, 1993, is “crystal clear,” he told BuzzFeed News in an interview at Hill Correctional Center in Galesburg, Illinois.

He spent the night at his friend Mel Gonzales' house. Adam brought his Super Nintendo controllers and games, but he forgot the console, so the boys spent the night drawing. At 10 p.m., Family Feud came on. After they watched the game show, the boys went to sleep in the front room of the apartment.

Around 4 a.m., Adam's brother, Mike Gray, and mother showed up in an agitated state.

Mike asked Adam, repeatedly, “Where you been at?”

“What do you mean? I’ve been here sleeping,” Adam told Mike.

Looking at Adam's zombie-like appearance and the imprint of a quilted blanket on his face, Mike believed his brother. He insisted Adam come with him to his place where he would be safe from the “lynch mob” combing the neighborhood for him.

When Mike answered his door at 6 a.m., he was greeted by two plainclothes detectives. The officers told him they needed to take his brother down to the station to ask him a few questions. Mike told Adam to take his books and bag so he could head straight to school after he talked to the cops.

“So I explained that to the cops. And they were like, 'Well, what’d you do then?’ I was like, 'The fuck you mean I do then? I went to sleep.’”

Adam knew that he was being taken in for questioning about the fire. Still, in his mind he had nothing to hide.

“To me, it’s Kasey, we’ve been beefing for six months before that,” Adam Gray said. “So that had no credibility in my mind. She’s bullshitting.”

Gray was put in an interview room on the second floor of the station at 51st and Wentworth. He remembers the silhouettes of people going in and out of the room on the other side of the two-way mirror, which he thought was kind of cool.

Around 7:30 a.m., a group of investigators led by Assistant State’s Attorney James Brown and Chicago Police Detective Nick Crescenzo came into the room. Brown read Gray his rights off a little card, then asked him if he would be willing to talk about the previous night. He said no problem. He told the investigators that he spent the night at Gonzales' house, about forgetting his Nintendo console, watching Family Feud, and going to sleep around 10.

“So I explained that to the cops and they were like, 'Well, what’d you do then?' I was like, 'The fuck you mean I do then? I went to sleep,'” Gray said.

The investigators continued to push Gray on what he did after he went to sleep. When he started to cry, they left him alone for a bit. This went on for hours. Each time they asked him, Gray maintained he had nothing to do with the fire. Asked if he ever requested a lawyer or to see his brother or mother — who both said that they were at the station that morning trying to get to him — he said he never thought to ask.

Later that morning, Gonzales arrived at 51st and Wentworth and was taken into a separate room to be questioned. Gray was not aware during his interrogation that his best friend was also being questioned until investigators started confronting him with Gonzales' answers.

“That’s a lot of how they were mind-fucking me. They would come to me with some of the answers that I had given them and tell me, ‘Well, we talked to Mel, and Mel doesn’t remember watching Family Feud,'” Gray said.

Pressed for information about Kasey Paris and Gray, Gonzales gave investigators what appeared to be a break in the investigation. He told them that nine months prior, Gray said he wanted to throw a bomb through Paris’s window.

According to Gray, after six hours of interviews, Detective Crescenzo came in and spoke to him alone. “He said, 'Look, man, I believe you, I believe that you didn’t have anything to do with it. The only way you’re going to get out of it is if you basically say that you did it,'” Gray said. “So I said, 'OK, I did it.'” (Crescenzo later testified that he never spoke to Adam alone that morning and denied that he ever coerced him to confess.)

After that, Gray remembers the attitude inside the station changed. Gray said the assistant state’s attorney came into the room smiling and said to him, “You have something you want to tell me?” He said he proceeded to “ad lib” an explanation.

Gray told the investigators that at 2 a.m. he snuck out of Gonzales' house. In the alley, he grabbed a discarded plastic gallon milk jug. Then he walked half a block to the Clark gas station. At Clark, Gray filled up the jug with $2 worth of gas and made his way to 4139 S. Albany St., where Paris lived. He said he entered through the back door and doused the wooden stairs with gasoline. After he ignited the gas with a lighter, he ran back to Gonzales' house, tossing the jug in an alley along the way. When he got back to Gonzales' place, he smashed the lighter, flushed it down the toilet, and went back to sleep. Investigators got him McDonald’s while they waited for the statement to be transcribed so he could sign.

One puzzling detail that emerged later on after tests were run on the debris from the scene was that no gasoline was found. Nevertheless, Adam signed the statement and was transferred to Chicago’s juvenile corrections center, nicknamed the "Audy Home." After being locked up for the night, the most crushing moment for him came the next day when he met his lawyer.

“He told me, ‘Look, man, you’re going to be sitting here at least 10 or 11 months with what you’re facing.' That, to me, it was too much to handle. I became suicidal after that.”

Gray remained at the juvenile center for three years until he turned 17, when he was sent to the Cook County Jail to await trial for the murders of Peter McGinnis and Margaret Mesa.

Gray’s trial began in April 1996. Prosecutors portrayed him as a rage-filled teenager who had reached a boiling point because of his unrequited affection for Kasey Paris.

Paris testified that Gray forced her to break up with Gonzales, then continued to threaten to hurt both of them if they ever got back together. She told the court that for months he had skulked around their neighborhood yelling vile statements at her like “You’re going to die, die, die” and “You bitch, you’re a whore.” She said that the day before the fire, Gray told her to watch her back. (Gray does not dispute that he told Paris to break up with Gonzales months before the fire, but says that he didn’t speak to her after that and denies threatening her.)

Other witnesses for the prosecution corroborated the details of Gray’s signed confession. Brenda Thomas, a Clark gas station attendant, testified that she sold him $2 of gas that night at 2 a.m. Then, the next night when the police came to see her, she identified Gray out of a set of Polaroid pictures of young boys from the neighborhood.

Crescenzo testified that while the assistant state’s attorney was taking Gray’s statement, he left the police station and went to the scene where he recovered a gallon milk jug that matched the description Gray gave of the container. He told the court he found it in the vicinity of where Gray said he'd tossed it and it smelled like gasoline.

In court, Assistant State’s Attorney James Brown read Gray’s statement aloud to the jury. It concluded with this exchange:

“Now, could you tell me why you did what you did with the gasoline?”

“Because I wanted to kill her.”

“Kill who?”

“Kasey.”

Both Crescenzo and Brown testified that at no time did they pressure Gray into confessing.

For the defense, 16-year-old Mel Gonzales testified that Gray had never threatened him or told him that he wanted to burn Paris’s house down. He said that morning the police showed up at his house at around 8 a.m. and took him to 51st and Wentworth. He said investigators questioned him “seven or nine” times.

Gonzales testified that the investigators “asked me if I love my parents to tell them what they want to hear, or they would put me in jail for the rest of my life.” After that, he said that Gray said he was going to throw a bomb through Paris's window. Gonzales said that he didn’t take the bomb threat seriously. And when the prosecutor asked him on the stand if he was afraid of Gray, he said no.

Gonzales, his sister, and his mother all testified that they had no knowledge of Gray sneaking out of their house that night to start the fire. If he had snuck out and snuck back in, he hadn't woken anybody up.

When it came time to discuss the evidence from the scene at 4139 S. Albany St., investigators Rokosik and Gruszka took the stand and outlined the visual observations they had made that night that suggested arson.

But Gray told BuzzFeed News that “for a glimmer I started to have a hope at the trial” when the crime lab technician testified that there was no gas found at the scene. A Chicago Police criminologist said his tests on the samples taken by Rokosik revealed heavy petroleum distillates (HPDs) with a high boiling point average. His tests on the milk jug also showed the presence of HPDs, but with a medium boiling point average. Neither matched the composition of gasoline, which has a low boiling point average.

At his sentencing, the prosecutor asked the judge to “contain the fire within Adam Gray” and put him away for life.

If there was no gas, this fire could not have happened the way Gray said it did in his confession. Gray said his lawyer told him privately that he had a good chance.

That’s not how it played out. The state insisted that while the test results didn’t show gasoline, the chemicals in the debris and milk jug showed the presence of an accelerant. This, plus the investigators’ testimonies that there were visual clues of arson at the scene and Adam’s confession, was enough for the jury.

At his sentencing, the prosecutor asked the judge to “contain the fire within Adam Gray” and put him away for life.

They needn’t have asked. Because the crime was felony murder, Adam received an automatic sentence of life without parole.

In 1992, four years before Adam Gray’s trial, the National Fire Protection Association published a groundbreaking document on fire investigation — NFPA 921.

“Alligator char, for instance, is nothing more than a historical footnote,” Denny Smith, one of the authors of NFPA 921, told BuzzFeed News. "It’s simply a term that has lost its meaning. There is no direct correlation to any specific cause in seeing these shiny blisters."

Bold new claims like this were bolstered by several experiments run in the late ’80s and early ’90s by fire scientists that proved an accidental fire could show some of the same aftereffects as a blaze started with an accelerant. One of the most famous of these experiments was the Lime Street Fire, which saved a Florida man from the death penalty.

It took commonly accepted visual indicators of arson and determined they were myths passed down for decades without any scientific proof.

In 1992, veteran fire scientist John Lentini was called to testify as an expert in a capital murder case against Gerald Lewis, who was accused of killing six people in a fire that burned down his family’s Jacksonville home.

Investigators ruled the fire an arson based largely on visual observations such as irregular burn patterns on the floor that made it appear as though something had been poured on it. Lewis claimed that the fire started when his living room couch accidentally caught fire. Lentini was puzzled by the fact that they had found no gasoline in the house. Still, he was ready to testify against Lewis based on the evidence. Before testifying, however, Lentini wanted to test the case against Lewis — and he wanted to do it in a radical way.

Lentini got permission to burn down the condemned home located next door to Lewis’s. He started the test-burn by lighting a similar couch on fire. Within minutes, and without the use of an accelerant, the whole room became overwhelmed by the blaze.

Afterward, Lentini found the same conditions: a heavily charred floor with irregular burn patterns. His experiment revealed that a fire that starts when a couch accidentally catches fire could look like a fire started by gas. He told the prosecutor that he could no longer testify, and shortly thereafter the charges were dropped against Lewis. Lentini told BuzzFeed News that after 1992, the fire investigation communities' “collective heads exploded.”

However, it would take many more years for these advances to have an effect in the courtroom. There have been 22 exonerations since 1989 in which defendants were cleared of arson charges because of new scientific evidence, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. Half of these happened in the last four years, and 5 of the 22 exonerations occurred in 2015. All 5 of the exonerations in 2015 were for crimes alleged to have occurred before NFPA 921 was published.

It would take more than 20 years for leaders in the field to even learn the name Adam Gray. And it might never have happened if not for someone who had no expertise in fire science at all.

Rebecca George was a 21-year-old art teacher at the Audy Home, Chicago’s juvenile detention center, when she met Adam Gray in 1994. Her supervisor thought that it would be therapeutic for Gray if George drew with him.

“He wasn’t very responsive, didn’t seem very interested,” George told attorneys during a deposition taken in 2015. They never really developed a relationship. However, after Gray was convicted, George reconnected with him while doing outreach work. They exchanged a few letters.

In 2000, George learned about a study on inmates who had grown up in the juvenile system and experienced developmental delays. She reached out to former students, including Gray, and asked for permission to submit their letters to the study. Gray wrote her back in an accusatory tone: If she didn’t care about his case then, why did she all of a sudden care now that he was locked up forever?

All the other kids whom George worked with confessed their crimes to her. And not just what they were locked up for, but other things they had done, too. Not only had Adam Gray never confessed, but in his letter he also professed that he was innocent. “And I never had anyone tell me they were innocent,” George said. “It just had a big impact on me that there was a possibility this person was wrongfully convicted.”

Suddenly, the prosecution’s case seemed to unravel.

After a couple years of pulling together court documents, and a few failed attempts to gain assistance from journalists and attorneys, George was able to assemble a team that included an investigator and a former staffer at Northwestern University’s Medill Innocence Project. Together, they tracked down people connected to the case who hadn’t talked about Adam Gray or the fire at 4139 S. Albany in nearly 15 years. Suddenly, the prosecution’s case seemed to unravel.

Two of the first people George met were Will and Hope Rogers, who lived next door to the Paris family. On the night of the fire, Will Rogers, an off-duty Chicago firefighter, told George he was the first person to race into the burning house, but failed to get to the victims because the fire was already overwhelming.

Hope Rogers told George she had seen a high school–aged boy in the yard next door that night who appeared be wiping his hands in the grass. She was familiar with Adam Gray, who lived across the street, and said it wasn’t him who she'd seen. Both she and her husband said they were never interviewed by police. In 2006, the Rogers signed affidavits prepared by George and her team.

George was getting progressively deeper into the investigation. Finding new witnesses like Will and Hope Rogers was one thing. But then, in an even more bizarre twist, trial witnesses started to change their stories, too.

One witness who recanted her testimony was Brenda Thomas, the gas station attendant who testified that she sold Adam Gray $2 worth of gas in a milk jug the night of the fire. Thomas told George that when police visited her at work in the days after the fire, they showed her a photo array and asked her to identify the boy she'd sold the gas to. When she picked a photo that wasn’t Adam's, they made it clear that they wanted her to pick a different photo. According to her affidavit, she said she eventually picked Adam’s photo because of “nonverbal pressure.” Thomas said she testified against Gray because the police told her that she would go to jail if she didn’t appear in court.

One of the last people George went to see was Kasey Paris. She showed up at her house in Indiana and knocked on her door. Paris told George that at the time of the fire she was still mad at Gray for coming between her and Gonzales, so she told police that Adam had started the fire to get revenge.

According to her affidavit, Paris “had no factual knowledge to support the accusation and repeated coercion from the police” led her to implicate Gray. She claimed that the pressure from police made her start to believe her own story. She said she was neither afraid of nor intimidated by Gray, and had no firsthand knowledge that he threatened to kill her.

Paris’s affidavit, signed in March 2007, was one of the last documents that George collected. There were other people she identified who she thought could help, but either she couldn’t find them or they didn’t have any useful information. She even showed the Rogerses several yearbooks from neighborhood schools in hopes that they would recognize the boy Hope Rogers saw cleaning himself off in the grass that day, but nothing ever came of it.

Momentum started to slow, and while George still had an interest in Gray’s case, she felt she had taken it as far as she could. “At a certain point, I turned it over, you know, to these law firms, and got on with my life,” she said. “This was not my intention to go as far as I did.”

When Chicago firm Jenner & Block responded to a letter from George about the case, she copied all her files — every affidavit, every email — and sent her dossier on Adam Gray to the big downtown firm.

Brij Patnaik, an associate at Jenner & Block, came on the case in 2010. He had read up on the shifts in arson investigation over the years, so he brought in three well-known fire scientists: John Lentini, Denny Smith, and Gerald Hurst.

Hurst, a chemistry Ph.D. who started his career testing explosives for the government, had famously investigated the case of Cameron Todd Willingham, a Texas man convicted of murdering his three children in a house fire in 1991.

In his report on Willingham to then-Gov. Rick Perry, Hurst disputed several claims by the original investigators. Some of this evidence included irregular burn patterns on the floor — similar to the patterns Lentini had disproven as arson evidence in the Lime Street Fire — and the presence of “crazed glass,” glass believed to crack a certain way due to rapid heating, which scientists had also dispelled as an arson myth years before.

Those findings, along with the presence of exposed wiring discovered next to a space heater in Willingham’s house, led Hurst to conclude that the cause of the fire should have been ruled undetermined. Despite these efforts, Perry denied Willingham’s request for clemency in 2004, and he was put to death that same year. To this day, Hurst’s work has people questioning whether or not Texas executed an innocent man.

For the Gray case, the three men examined dozens of photographs, chemical tests from the debris and milk jug, police reports, and testimony from the trial. Hurst said during his deposition that he put in 100 to 200 hours looking at the photos alone.

Collectively, the experts delivered a scathing review of the 1993 investigation of the South Albany Street fire. In his report, Smith called the determination that a liquid accelerant was present based on alligator charring “speculative and not supported by any evidence or scientific research.” He wrote that after investigators failed to find gasoline at the scene, they relied on an “absence of evidence” and the elimination of other accidental causes, such as electrical. He called this methodology “unacceptable, unethical, and improper.”

Smith told BuzzFeed News that the fact that investigators took just two samples from the scene was troubling. “If an investigator goes to a fire scene and takes 100 samples and only one comes back positive, no one is going to say you’re only 1% right,” Smith said. “In fact, if you find one sample out of 100, they’re going to say you’re 100% right!”

During his deposition, Hurst was asked about the milk jug believed to have transported the gasoline dumped on the back stairs, only later revealed not to contain any gasoline. As for the detective who testified that he smelled gasoline on the jug when he recovered it near the scene, Hurst suggested simply that the detective was fooled by his own nose. “If he was able to smell it, I guarantee they would have found it,” Hurst said. “If you can smell it, you can find it in a lab, it’s that simple.”

“I’m also troubled by the milk jug in this case,” Smith told BuzzFeed News. “The facts don’t line up. There’s no gasoline in the milk jug. So how does the gas get transported to scene?”

In 2012, Lentini, Hurst, and Smith submitted their findings to Adam Gray’s defense. All three determined that based on the available evidence from the investigation, the cause of the fire at 4139 S. Albany St. should have been ruled undetermined.

Smith, who acknowledges that he was taught in the 1970s to look for these same visual indicators of arson, said their review is not about putting down the original team of investigators.

“This isn’t about casting blame and saying what a lousy job they did,” said Smith. “But you could actually say, in some respects, what they did was consistent with what a lot of investigators did at the time.”

In 2012, Gray’s attorneys from Jenner & Block — now working with the University of Chicago Exoneration Project — filed a second post-conviction petition with an innocence claim based on their fire science analysis.

The state of Illinois agreed with the defense that Gray had a right to a hearing on the new fire science evidence. However, it would take the court until 2015 to make a decision on whether to grant Gray an evidentiary hearing. In June 2016, Gray will get an evidentiary hearing in his case. It will be like a mini-trial, held over three days, where he will be given the opportunity to present new evidence. The hearing will determine whether the jury might have reached a different outcome if it had access to the new evidence. Best-case scenario for Gray is he gets a new trial.

The case that his attorneys intend to make is that Gray is innocent because arson science now shows there is no way this fire could have happened the way Adam described it in his confession.

“We anticipate the state will likely argue [at the evidentiary hearing] that there is other evidence of arson because Adam confessed,” Terri Mascherin, a partner at Jenner & Block, told BuzzFeed News. “For lots of reasons, we think that the confession is not reliable.”

If Gray gets a new trial, that puts him back at square one. (Mascherin said she believes that Jenner & Block, who is representing Gray pro bono, would stay involved.) If a new trial were to happen, original witnesses from the 1996 trial could be called to testify, including Kasey Paris.

After BuzzFeed News contacted her for this story, Paris responded that she “really would rather close that chapter in my life. It will be 24 years [in March] and it is still a great pain for me and my family.” She confirmed that prior to recanting her testimony in 2007, she went to see Gray in prison. “It was for my personal closure more than anything."

Paris told BuzzFeed News that she believed recanting was the “fair and right thing do” so that if Gray gets a new trial, the testimony that will be used will be her words as an adult and not “a terrified 14-year-old child.”

“As an adult, it did occur to me the way I was asked questions and the types of questions I was asked were to make Adam appear guilty,” Paris said. “Is he guilty? I still think it’s very probable and highly likely. If he isn’t, I feel terrible that he has spent his life locked away. It isn’t my place to make that choice.”

Asked about the prospect of his brother coming home, Mike Gray is optimistic. He talks about putting his brother to work and how he thinks the love of computers he had as a young kid could make Gray a “great network guy” on the outside. Mike believes that it will happen because, as he said repeatedly, “science doesn’t lie.”

“We’re moving forward. And if the end result is the same, if it takes another year to get to the end result and Adam is free, you know what, I can live with that.”

After 23 years in jail, 37-year-old Adam Gray considers himself an “old man.” When he talks about his case he is careful to hedge his bets. However, there is one thing that Gray said will never happen.

“I’ve been locked up almost twice as long as I was ever free. I’ve long ago made peace with the idea of dying in prison,” Gray said. “If I had to plead guilty to get out tomorrow, I’d tell them to go fuck themselves — no, it’s not going to happen. Leave me in prison.”