On a Saturday afternoon in late November 2014, Tamir Rice was shot by police while playing in a Cleveland park across from his mom’s house. The 12-year-old boy was carrying a toy pistol with the orange indicator removed. The Airsoft BB gun looks almost identical to a real weapon.

“It’s probably fake,” a 911 caller who saw Rice pointing the gun in the park told the police dispatcher, “but he’s waving it around at people… it’s scaring the shit out of me.”

Minutes later, police arrived at the park and pulled their car within feet of Rice. Cleveland Police Officer Frank Garmback, 46, drove the patrol car, and a rookie officer, Timothy Loehmann, 26, rode in the passenger seat. Before the vehicle came to a complete stop, Loehmann opened the passenger side door and shot Rice in his torso. A police statement said that the officers asked Rice to raise his hands but the boy instead reached for the gun at his waist.

Jeffrey Follmer, the Cleveland Police Patrolmen’s Association president, said Garmback called in to the station right after the incident. “It’s already a mess,” he said. “We have a 20-year-old male shot.” A full four minutes later, the officers began administering first aid to Rice.

Rice was eventually taken to a hospital where he had surgery. He died early in the morning on Nov. 23, 2014.

Three days later, the Cleveland police department released a video of the incident which showed that Loehmann shot Rice within two seconds of arriving on the scene. The police said they feared for their lives, but Rice’s family said the shooting looked unnecessary.

“The video shows one thing distinctly: the police officers reacted quickly,” the Rice family said in a statement. “It is our belief that this situation could have been avoided and that Tamir should still be here with us.”

On Monday, a grand jury declined to file criminal charges against either officer.

News Coverage

Following the shooting, a series of articles published on Cleveland.com, the online arm of the Cleveland Plain Dealer and Northeast Ohio Media Group, focused on the criminal records of Rice’s family. The articles drew a negative response from many readers who found the depiction of Rice and his parents unnecessary and offensive.

The day after the shooting, Cleveland.com reported that in 2012 Samaria Rice faced drug possession and trafficking charges in Cuyahoga County. She pleaded guilty and was sentenced to three years probation

Two days later, on Nov. 26 2014, Cleveland.com posted a story citing court records showing that Rice’s father, Leonard Warner, has multiple convictions on domestic violence charges.

Critics found these details irrelevant to the shooting death investigation of Rice and called it character assassination — likening the stories to the criticism against 18-year-old Michael Brown after he was fatally shot by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, on Aug. 9, 2014.

Chris Quinn, vice president of content for the Northeast Ohio Media Group, defended the organization’s coverage in an op-ed article in which he writes, “One way to stop police from killing any more 12-year-olds might be to understand the forces that lead children to undertake behavior that could put them in the sights of police guns.”

The Cleveland Plain Dealer’s ombudsman Ted Diadiun echoed Quinn’s defense in an article titled “Blaming the media — social and otherwise — is foolish and fruitless.”

The Video

Rice’s mother, Samaria, said that after the shooting, two boys knocked on her front door and told her that her son had been shot. She ran across the street to see what happened.

When she arrived at the scene, she says she found her son lying on the ground bleeding, her 14-year-old daughter in the back of a police car, and the police standing around. Her daughter later told her that police tackled and handcuffed her.

Samaria Rice said she was stopped by police and threatened with arrest if she didn’t calm down.

In statements given shortly after the shooting, police officials said that Rice was with a group of boys when he was shot. They said that Loehmann saw Rice take what looked like a pistol under a table in the park and put it into his waistband.

These statements were inconsistent with the video released by Cleveland police on Nov. 26, 2014.

A family attorney confirmed that Rice went with friends to the park on that Saturday, but throughout the seven-minute video, Rice is alone. In the video, there is no group of boys visible anywhere nearby.

In the video, when police approach Rice, he is standing next to the gazebo, and the gun is not visible. Rice makes no movements to reach under a table when the police arrive or in the seconds before the police car enters the frame. Follmer, the police union president, said that Loehmann saw Rice take the gun off the top of the table and put it in his waistband as the police car was driving toward the park.

The police union also reported that Loehmann asked Rice to raise his hands three times. An official statement from the Cleveland police released on Nov. 23, 2014 stated that the officers “advised him to raise his hands,” adding “the suspect did not comply with the officers’ orders and reached to his waistband for the gun. Shots were fired and the suspect was struck in the torso.”

In the video, Rice does reach toward his waistband right before he is shot. While it’s possible that the officer told Rice to raise his hands three times, Rice is shot within seconds of the police car arriving on the scene. Follmer told BuzzFeed News that Loehmann had shouted the demands from the car as they were driving toward Rice, but the car moves very quickly and pulls up within feet of Rice.

In a press conference two days after the shooting, Cleveland Police Chief Calvin Williams said that the video corroborated the officer’s initial description of the shooting.

Officer Loehmann

Loehmann became a Cleveland police officer in March 2014, eight months before he shot Rice.

Documents obtained by BuzzFeed News revealed that when Loehmann left his old job as a police officer in Independence, Ohio, he was in the process of being fired for dismal performance — but was given a chance to resign before that happened.

Father Gerard Gonda, president of Benedictine High School in Cleveland, where Loehmann graduated in 2007, described him as polite, kind, mature, congenial, and gentle.

“Any connotation of racial animosity [regarding Loehmann] is unfair,” Gonda told BuzzFeed News. “It’s unfortunate that it happened at the same time that Ferguson took place,” he said, referring to the police shooting of Michael Brown. “I think each incident has to be looked at in its own context.”

Following the shooting, the Cleveland Division of Police released the personnel files of Loehmann and Garmback.

The 46-year-old Garmback’s personnel file does not include any other incidents where excessive force was questioned since he joined the force in 2008. In 2011, Officer Garmback received an award after he shot a robbery suspect.

Calls to Garmback’s family and friends were not returned.

In December 2014, the City of Independence, Ohio, where Loehmann first worked as a police officer, released documents that described him as emotionally unstable and unable to properly use a firearm.

Loehmann worked as a patrolman in Independence for less than one year prior to joining the Cleveland Police Department in 2014. He was ultimately asked to resign from his job or be fired, according to the documents. This contradicts the information he provided in his job application to the Cleveland Police Department two years later.

The Independence documents offered a damning and troubling account of Loehmann’s emotional state and ability to follow directions.

According to the documents, in a November 2012 letter to the Independence Police Department’s human relations director recommended Loehmann’s termination, Independence Deputy Chief Jim Polak explained that for much of his time on the force, Loehmann “was distracted and weepy.” He could not “follow simple directions, could not communicate clear thoughts nor recollections, and his handgun performance was dismal.”

Polak provided a specific example of an emotional breakdown Loehmann had while working with another officer, Field Training Officer Sgt. Tinnirello.

“During this drive, Sgt. Tinnirello continued to speak with Tim about his problems, and Ptl. Loehmann continued with his emotional meltdown to a point where Sgt. Tinnirello could not take him into the store, so they went to get something to eat and he continued to try and calm Ptl. Loehmann. Sgt. Tinnirello describes the recruit as being very downtrodden, melancholy with some light crying. … Some of the comments made by Ptl. Loehmann during this discourse were to the effect of, ‘I should have gone to NY,’ ‘maybe I should quit,’ ‘I have no friends,’ ‘I only hang out with 73 yr old priests,’ ‘I have cried every day for 4 months about this girl.’”

According to Tinnirello, Loehmann told him his behavior was due to a bad breakup with his on-again, off-again girlfriend.

In the personnel file, Sgt. Tinnirello reported three other incidents in which he was concerned about Loehmann’s behavior.

“Individually these events would not be considered major situations,” Polak wrote. “But when taken together they show a pattern of a lack of maturity, indiscretion and not following instructions.”

The other reported incidents include one case in which Loehmann left his gun unsecured in his locker overnight after he was specifically told that was unacceptable. In another instance, he took off a bulletproof vest he was supposed to be wearing because he said he felt “too warm.”

Polak finished, “for these reasons, I am recommending he be released from the employment of the City of Independence. I do not believe time, nor training, will be able to change or correct these deficiencies.”

But rather than firing Loehmann, Polak met with Loehmann and Tinnirello on Dec. 3, 2012, and gave Loehmann the opportunity to resign.

Loehmann agreed to leave, and Independence accepted his written resignation.

Cleveland police told BuzzFeed News that while there was no review of Loehmann’s file, there is no “written policy mandating a review of an applicant’s previous employer personnel file.”

The Cleveland Police Department confirmed to BuzzFeed News that during Officer Loehmann’s background check “Cleveland Police detectives did not review his Independence Police Department personnel file.”

“While our policy does not require obtaining a personnel file prior to employment, the Cleveland Division of Police has amended our policies to request a personnel file from previous employers,” a Cleveland police spokesperson said.

Loehmann’s woes in Independence called into question several details that were reported after Rice’s shooting.

In an interview posted to Cleveland.com, his father, Fred Loehmann, said his son left Independence because he “grew tired of the slow pace of suburban policing.”

In his application to become a Cleveland police officer, Loehmann made no mention of his troublesome employment in Independence. Instead, he said that he “resigned for personal reasons” from the department, and wrote that he faced no disciplinary actions.

A year later, newly released documents showed that Loehmann also failed a test to become a deputy in the Cuyahoga County Sheriff’s Department. On a written exam that requires that recruits score at least a 70% to pass, he scored a 46%.

Other reports and investigations

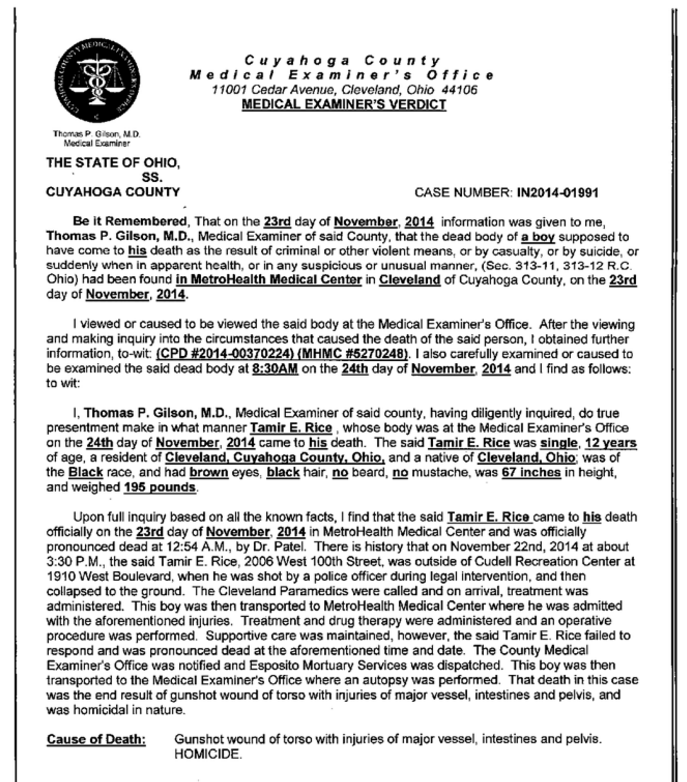

An Ohio medical examiner officially ruled Tamir Rice’s death a homicide. According the coroner’s report, Rice died from a “gunshot wound of torso with injuries of major vessel, intestines and pelvis.”

In January 2015, Rice’s family filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the city of Cleveland and police officers who fatally shot Rice.

That same month, new surveillance video released showed Cleveland police officers forcing the boy’s 14-year-old sister to the ground before handcuffing her and putting her into a police car at the scene of her brother’s fatal shooting.

The city also signed a consent decree with the Department of Justice in May 2015 that includes reforms to its use of force policy based on findings that police officers engaged in a pattern of reckless behavior.

In May 2015, six months after he was killed, Rice’s family cremated his remains. Samaria Rice made a “maternal decision” decision to lay her son to rest, the family’s lawyer said.

In June 2015, Cuyahoga County Prosecutor Tim McGinty indicated that he intended to present the case to a grand jury to determine if the officers involved in the shooting would face criminal charges.

“This case, as with all other fatal use of deadly force cases involving law enforcement officers, will go to the Grand Jury,” McGinty said. “That has been the policy of this office since I was elected. Ultimately, the Grand Jury decides whether police officers are charged or not charged.”

Rice’s family had previously spoke out that they opposed the grand jury, as they felt that there was enough probable cause to charge the officers based on the evidence that has already been made public.

In June 2015, after community leaders invoked a rarely used Ohio law that allows people to request a prosecutor bring charges, Judge Ronald Adrine of the Cleveland Municipal Court issued a statement of probable cause that Loehmann and Garmback should be charged in Rice’s death.

Following the judge’s statement, Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson said that Aldrine’s findings would be turned over to McGinty’s office to be presented to the grand jury.

After the grand jury proceeding commenced, in the Fall 0f 2015, a series of reports released by the Cuyahoga County Prosecutor’s Office found the shooting tragic, but justified and reasonable.

The first two reports, released in Oct. 2015, compiled by a senior chief deputy district attorney from Denver and a retired FBI agent, found that Loehmann reasonably believed Rice posed a threat when the rookie officer opened fire in November 2014.

“There can be no doubt that Rice’s death was tragic and, indeed, when one considers his age, heartbreaking,” wrote S. Lamar Sims, the senior chief deputy district attorney in Denver. “However, for all the reasons discussed herein, I conclude that Officer Loehmann’s belief that Rice posed a threat of serious physical harm or death was objectively reasonable as was his response to that perceived threat.”

In both reports, officials said Rice seemed to have reach to his waistband and the officer responded to what appeared to be a threat.

“Unquestionably, the actions of Rice could reasonably be perceived as a serious threat to Officer Loehmann,” Kimberly A. Crawford, the retired FBI agent, wrote in her report.

McGinty said the reports were released in an effort to maintain transparency and an “intelligent discussion” on the use of police force.

After the reports were released, Samaria Rice said she was “very disappointed” in how McGinty was handling the investigation, and asked that he step aside to allow an independent prosecutor to review the case.

“Do you all think the killing of my child was constitutionally justified?” she said. “I am praying the public continues to ask questions and seeks the truth. I want to thank everyone for their prayers and support. Please continue to support us in getting justice for Tamir.”

Rice family attorney Jonathan Abady accused McGinty of mishandling the case, saying that “the flaws and inefficiencies are too numerous to cite at a press conference.”

In a letter he sent to McGinty, Abady said that the prosecutor’s office has delayed the grand jury process and shown bias in selecting pro-police experts who argued that the officer was justified in shooting Tamir because he “posed a threat of serious physical harm or death.”

“It now appears that the grand jury presentation will be nothing short of a charade aimed at whitewashing this police killing of a 12-year-old child,” Abady stated in his letter.

Despite calls for his removal, McGinty’s office rebuked the notion that he would step aside in the case.

In a third report released in Nov. 2015, W. Ken Katsaris, a Florida law enforcement officer and instructor who has previously served as a police officer, a deputy sheriff, a highway patrol trooper and a Chief Law Officer in Florida, wrote, “This unquestionably was a tragic loss of life, but to compound the tragedy by labeling the officer’s conduct as anything but objectively reasonable would also be a tragedy, albeit not carrying with it the consequences of the loss of life, only the possibility of loss of career.”

In the report, Katsaris noted that the 911 dispatcher did not inform Loehmann and Garmback that the caller had indicated that the pistol might be fake and the person carrying it was “probably a juvenile.”

Katsaris wrote that given the circumstances, “the only objective reasonable decision to be made by Loehmann was to utilize deadly force and deploy his firearm.”

Following the release of Katsaris’ report, attorneys for Rice’s family criticized Cuyahoga County Prosecutor Tim McGinty’s decision to release the “biased, pro-police reports that purported to justify the shooting.”

“Regrettably, with the release of yet another utterly biased and shamelessly misguided ‘expert report’ the County Prosecutor is making clear his intention to protect the police from accountability under the criminal laws, rather than diligently prosecute them,” the family’s attorney Jonathan Abady said Thursday in a statement provided to BuzzFeed News.

McGinty responded, “This is a far more thorough investigation than has ever been done in this county, and there has never before been such an open process.”

“When it comes to police use of deadly force cases, I could simply make a ruling as to whether a police officer’s actions were justified by law or violated the law, with no need to explain my decision,” McGinty said.

“Instead, in all fatal use of deadly force cases, I have chosen to use a process by which evidence is carefully investigated by another separate and neutral police agency (in this case, the Cuyahoga County Sheriff’s Office).”

In December 2015, Ohio prosecutors released the first statements by Loehmann and Garmback.

The statements were dated and signed Nov. 30, 2015, indicating that they were taken more than one year after the fatal shooting at Cudell Recreation Center on Nov. 22, 2014.

According to the statement, Loehmann said he and Garmback were responding to a call of a “male waiving a gun and pointing it at people” and that “this was an active shooter situation.”

In their accounts, both officers describe Tamir as a “male matching the description of the suspect,” and make no reference to the fact that he was actually 12 years old.

“The male appeared to be over 18 years old and about 185 pounds,” Loehmann wrote.

Garmback, whose testimony consisted of a numbered list of the facts of the day, wrote: “12. I thought the male was an adult. Over 18 years old.”

“As car slid, I started to open the door and yelled continuously, ‘show me your hands’ as loud as I could,” Loehmann wrote. “Officer Garmback was also yelling ‘show me your hands.’”

The rookie officer said he kept his eyes on the suspect’s hands “because hands may kill.’”

Then, Loehmann wrote, he saw Tamir lift his shirt and reach into his waistband.

“Even when he was reaching into his waistband, I didn’t fire,” he wrote. “I was still yelling the command, ‘show me your hands.’”

Loehmann said he saw Tamir pulling what appeared to be a gun from his waistband, his elbow coming up, and that “I knew it was a gun and it was coming out.”

The weapon, however, turned out to be the Airsoft BB gun that authorities have said looked like a real weapon.

“I saw the weapon in his hands coming out of his waistband and the threat to my partner and myself was real and active,” Loehmann wrote.