Billionaire Mexican drug lord Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzmán is fighting drug charges in Brooklyn that could send him to prison for the rest of his life — and he’s doing it on the US taxpayer's dime.

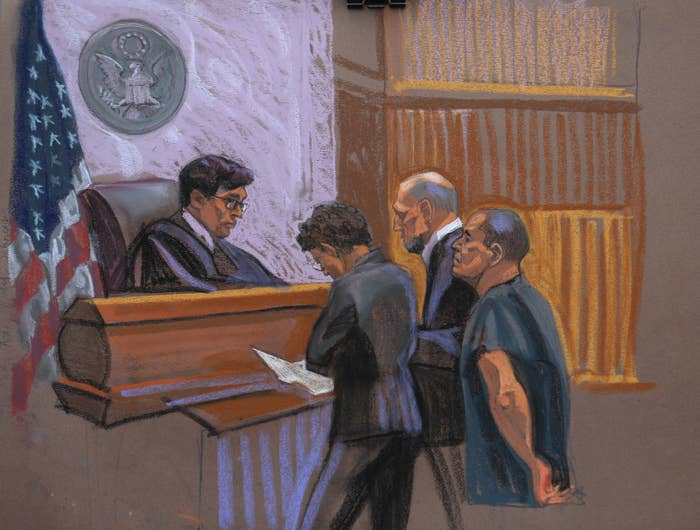

Public defenders Michelle Gelernt and Michael Schneider learned they’d be representing the world’s most notorious narcotics trafficker the same night he was extradited to the US from a Mexican prison. But since Guzmán's first appearance in a US courtroom on Jan. 20 alongside his public defenders, the federal government has been fighting to force Guzmán to foot the bill for his own lawyers.

A week after his initial court appearance, prosecutors in the Eastern District of New York wrote a letter to Judge Brian Cogan asking him to make a “strenuous inquiry” into Guzmán’s ability to hire a private attorney. The letter refers to Guzmán as “the billionaire leader of the Sinaloa Cartel, the world’s largest and most prolific drug trafficking organization” and notes that Forbes Magazine once included the drug lord on its list of the world’s richest men. In his criminal indictment, the US says it is seeking $14 billion from Guzmán.

Meanwhile, Gelernt and Schneiderare are vehemently defending their right to represent Guzmán. In a response to the government’s letter, they pointed out that prior to his extradition, Guzmán had little to no time to prepare for the American legal system. They claim that at the time he was being flown to the US, his Mexican attorney, Jose Refugio Rodriguez, was at the prison waiting for him, and had not been informed that his client was en route.

This debate over Guzmán’s right to a public defender came to the forefront at a court hearing Friday in Brooklyn. Gelernt told the court that Guzmán “has no ability to hire a lawyer” because, for one, the government has prevented him from having contact with his family who can arrange an attorney for him. In a related matter, Gelernt argued that the NYC jail where Guzmán is being held was being “unusually restrictive” in allowing him access to his attorneys and family members.

At the hearing, Judge Cogan ruled that Guzmán may continue to retain the services of the public defenders' office, but he must submit an affidavit that explains why he can’t afford his own lawyer.

“If the government doesn’t like the signed affidavit, they can investigate,” Cogan said.

In its filings the prosecution notes that they are “aware that Guzmán is making inquiries of private counsel” and believe it’s likely that he will hire a private attorney at some point. But the order by Cogan to disclose his financial status could be what forces Guzmán to make that decision.

Brooklyn Law School professor Bennett Capers, a former assistant US Attorney in New York, said that the mandate to submit a sworn financial affidavit could be an advantage to prosecutors because “if he were to lie on that form, they could charge him with perjury.”

In another court filing, Gelernt and Schneider informed the judge that Mexican officials had intended to meet with Guzmán on Friday outside the presence of his counsel to serve him his extradition papers. However, when the Mexicans arrived and found the two attorneys present, they left.

“The federal defenders are going to defend the hell out of this case,” Capers said. “They like taking on these difficult cases. This is what they do.”