The Trump administration is reaching back into Cold War history as it develops an increasingly aggressive strategy against Iran — one that could destabilize the regime in Tehran or even lead to its collapse.

Current and former US officials say a new campaign often described as “maximum pressure” has been informed by the strategy of Ronald Reagan, the conservative hero who is credited by some for paving the way for the demise of the Soviet Union.

Proponents of this view who advocate a similarly aggressive approach toward Iran say that Reagan’s combative policy toward the Soviet regime amplified the problems caused by its corruption and mismanagement and pushed it over the edge to collapse. One window into that mindset is the circulation within the administration of an out-of-print book published in 1994 called Victory: The Reagan Administration’s Secret Strategy that Hastened the Collapse of the Soviet Union. The book was written by Peter Schweizer, a favorite author of former Trump strategist Steve Bannon whose more recent work, the book Clinton Cash and the movie of the same name, roiled the 2016 election with allegations about the Clinton Foundation and its foreign backers.

In Victory, Schweizer chronicled the efforts of Reagan and his CIA director William Casey to deploy every tool of US power short of direct military confrontation to condemn the Soviet Union to the “ash heap of history,” as Reagan outlined in a 1982 speech to the British parliament. The strategy laid out by Schweizer includes economic warfare, which the US is waging against Iran in the form of an aggressive sanctions campaign. Several chapters focus on the more secretive aspects of that effort, from supporting dissident movements in Europe to funneling cash and weapons to Afghanistan’s mujahideen, who were fighting Soviet invaders. An official at the White House said it was “no secret” that the book has had some influence on policy.

One prominent booster of the book is Mark Dubowitz, the head of the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies (FDD), a Washington think tank with perhaps the most outside influence on the Trump administration’s Iran policy. Critics blame Dubowitz’s years-long opposition to the landmark nuclear deal the Obama administration struck with Iran in 2015 for Trump’s decision to pull out of the accord in May. (Dubowitz argues that he wanted to fix the deal, not scrap it.) They also see him as an architect of the new US sanctions. “If you want to know what’s going to happen next in Iran policy, there’s a pretty good bet that it’s whatever has been in the latest Mark Dubowitz or FDD op-ed,” said a former US official who worked on Iran policy under Trump.

Dubowitz has been touting Victory for more than two years and handing out copies, which he purchases used through third-party sellers on Amazon. Dubowitz, 50, said he viewed Victory as a blueprint. “It’s a fascinating book. There are a lot of specifics,” he said. “Many of the same ideas would be applicable against the Iranian regime.”

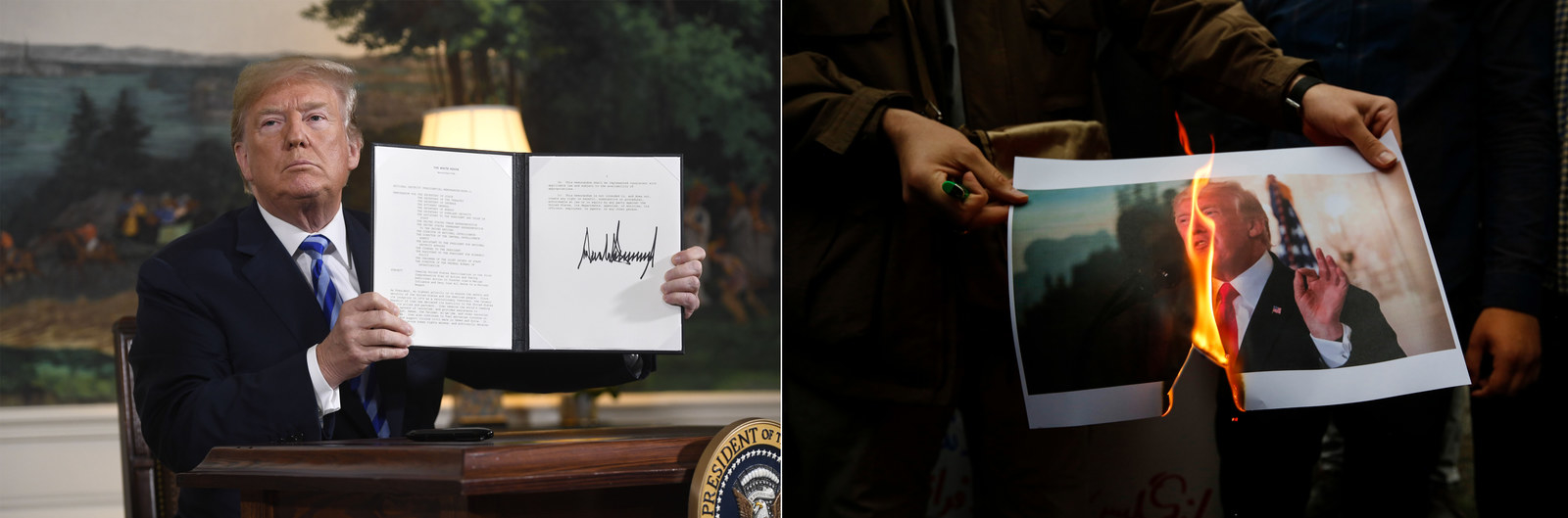

The campaign of maximum pressure has taken shape quickly in the wake of Trump’s withdrawal from the nuclear deal. The onset of new sanctions has pushed an already weakened Iranian currency into a tailspin, and the most punishing sanctions, on Iran’s oil and energy industries, will begin in November. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has brought a muscular new diplomacy to the State Department since arriving there in April, promising to bring the “swagger” back to Foggy Bottom as he promotes a harder line on Iran than his predecessor, while national security adviser John Bolton, who had called publicly for regime change in Iran, took office the same month. All the while, countrywide demonstrations that have been ongoing in Iran since December are presenting its leaders with their most serious challenge since 2009, when hundreds of thousands of Iranians poured into the streets following a disputed election result and were brutally suppressed. The protests have received only passing attention in US media, overshadowed by the scandals and political warfare that grip the country, but US officials have been paying close attention, seeing an opportunity to further undermine the Iranian regime. “The people are paupers while the mullahs live like gods!” Brian Hook, who was tapped by Pompeo to lead a new Iran task force at the State Department, said from the podium at an FDD forum after his appointment last month, channeling the chants of the demonstrators.

“This is a situation that is honestly ripe for, you know, exploitation.”

Sources involved in the field of democracy promotion — in which the US government backs programs that support human rights and civil society in authoritarian countries — said that US officials have expressed interest in using these programs more aggressively to challenge the Iranian regime. “The idea is you put some pressure on the government, and it also helps in the future if and when this regime falls,” said a former national security official who’s under contract to work on a project targeting sanctions evasion and corruption in Iran. “I think it’s generally good stuff. More accountability within the Iranian regime can only be a good thing.”

But he added: “This is a situation that is honestly ripe for, you know, exploitation.”

US officials, including Bolton, have insisted publicly that their goal is not regime change, but to push Iran to change behavior beyond just its nuclear program, including the detention of US citizens and support for proxy groups such as Hezbollah. They say it’s up to Iran to decide where the campaign of maximum pressure leads. “The sanctions deny the regime the revenues it needs to fund terrorism and all the other destabilizing activities Iran undertakes,” Hook said in an interview. “We are compelling Iran to make a choice between ending these activities or facing greater economic pressure and isolation. And that’s only a choice the regime can make.”

Yet even some who have helped to craft the hardline approach express concern about the potential consequences. “You’re putting a lot of pressure on the regime. So I think it’s only responsible to think through the implications of that pressure,” said a former senior official in the Trump administration who remains supportive of the approach but like others requested anonymity to speak candidly. “The biggest problem with that aspect of the strategy is you better have some sense of what you do after a collapse. You can’t just let it fall, or you’re going to have another Libya.”

The former official said these are questions the Trump administration is grappling with behind the scenes. “The people working on the Middle East portfolio are not naive. They understand what vacuums of power do in the region. I mean, they’re never good.”

“You better have some sense of what you do after a collapse. You can’t just let it fall, or you’re going to have another Libya.”

Trump made his opposition to Obama’s accord with Iran a central feature of his election campaign, calling it “the worst deal ever.” It offered Iran relief from punishing international sanctions in exchange for rollbacks on its nuclear program, which US officials have long worried is designed to create a bomb. Proponents of the deal argue that it encouraged Iran to normalize its behavior and staved off conflict — and allowed Iran’s opponents the space to address its other forms of aggression while easing the nuclear threat. Critics said the nuclear concessions weren’t tough enough, and that the deal only provided a regime that has called for the destruction of Israel and America with the financial resources to shore up its security forces and fund its allies in Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and elsewhere. As international corporations pull out of Iran and new sanctions undermine its battered economy, Trump has mused about the possibility of the regime’s collapse. “When I came into here, it was a question of when they would take over the Middle East,” he said in a recent interview. “Now it’s a question of will they survive.”

Current and former officials acknowledge that Trump could also change direction unexpectedly — as he did on North Korea, embracing talks with its dictator after months of confrontational rhetoric. Several sources who have worked on Iran policy under Trump said the self-styled dealmaker would welcome the chance to strike his own accord with Iran, one that addressed the criticisms leveled at its predecessor. He will have the chance to signal his intentions on Iran on Wednesday, when he appears at the United Nations General Assembly in New York to chair a Security Council meeting on nuclear proliferation. The assembly will also serve as a reminder that despite the US’s withdrawal, the Iran deal is still in place. Its other key signatories — Britain, France, Germany, and the European Union, along with Russia and China — remain committed to the deal, while the UN has said that Iran has so far met its terms, leaving the US to push for cooperation on its new sanctions. A senior official in the Trump administration said the sanctions are working well so far. “November is coming and the second round of sanctions being reimposed will be even more powerful,” the official said, speaking on condition of anonymity in line with government policy. “We have seen a material shift in behavior, and we’re already seeing significant reductions in oil purchases from Iran, which is precisely what we want to see.”

Richard Johnson, who was one of the State Department’s top experts on nuclear issues before he resigned over Trump’s withdrawal from the Iran deal, said he sees competing impulses in the administration: on the one hand, to change Iranian behavior and secure a better deal, and on the other, to use the opportunity of Trump’s presidency to engineer the regime’s downfall. For the moment, he said, both can be incorporated into the push for maximum pressure. “I really think that the folks driving this policy are true believers,” he said. “They truly believe that they can reinstitute a campaign of maximum pressure against Iran — that they can collapse Iran’s economy and bring it into recession and essentially bring the Iranians to their knees, to the point where they’re either coming to us and begging for talks, or where we’re essentially leading to regime collapse and something follows on.”

“I really think that the folks driving this policy are true believers. They truly believe that they can ... collapse Iran’s economy and bring it into recession and essentially bring the Iranians to their knees.”

Johnson, who worked extensively on both Iran and North Korea while in government and is now a senior director at the Nuclear Threat Initiative, a US nonprofit, sees Iran as the greater immediate threat for conflict with the US, despite the fact that North Korea already has nuclear weapons. “In terms of where I think hostilities are more likely to break out, I’m more concerned about Iran,” he said. “Because for whatever reason on North Korea, the president has decided to play nice.”

He added: “And the other thing that gets lost in the contrast with North Korea is that there’s no anti-North Korea lobby in Washington. And there is no parallel with regional states. You don’t have an Israel, you don’t have a Saudi Arabia, you don’t have a United Arab Emirates. There are so many other players on the Iran case that are driving this toward a potentially negative outcome.”

Despite Trump’s aggressive rhetoric on Iran, he has been clear that, like most Americans, he doesn’t want another costly intervention in the Middle East. Yet Trump did launch targeted missile strikes against the Syrian government after a chemical weapons attack last year, and Eric Brewer, a US intelligence veteran who was director of counterproliferation on Trump’s National Security Council (NSC) until May, said that rising tensions between Washington and Iran have increased the chances for escalation. He worried about whether the administration had adequately thought through how it might respond to Iranian provocations such as a gradual resumption of some nuclear activities that were halted under the deal. “The only option they’ve articulated is ‘don’t, or else,’ which could be interpreted as threatening some type of military action, but isn’t clear,” he said. “Vague threats of military action to prevent Iran from adding a few centrifuges aren’t credible or wise.”

He added: “There may be some who harbor this idea that a hardline approach could force Iran to overplay its hand, but I think that’s both unlikely and dangerous. I think we should be highly skeptical of anyone who claims they can confidently predict how this is all going to play out.”

II

“Of course, in public, they deny it,” Dubowitz, the FDD chief, said of the idea that the Trump administration’s policy on Iran is designed in part to destabilize and possibly collapse the regime. “I do think Bolton and others honestly believe that you can crack the regime the way Reagan cracked the Soviet Union.”

He said that regime change is the wrong term because of its connection to the US war in Iraq: “In that context, it means a mechanized force invading Iran and a long-term US occupation. That’s not going to happen.” He added that leveraging a new deal could be one outcome of the Reagan-inspired strategy he espouses — and that the collapse of the Islamic regime could be another. Any scenario that followed such a collapse, he added, would be better than the present reality — reasoning that even if a hostile regime led by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards took control, it would be weakened by internal divisions and likely rule without the legitimacy of Iran’s clerical establishment. “Here is the Cold War parallel. The Soviet Union is today’s Russia. Russia is dangerous. I don’t want to minimize that danger. It’s just not the existential threat that the Soviet Union was,” he said.

He did see one problem with the analogy. “Trump is not Reagan,” he said. “One must always keep that in mind.”

In Dubowitz’s view, it’s Pompeo, first as CIA director and now as secretary of state, who most ably channels the Reagan era. Dubowitz said that he handed Pompeo a copy of Victory after the former congressman from Kansas was named Trump’s first CIA director. According to Dubowitz, Pompeo read the book with interest and has shared it with colleagues at the CIA and State Department. “I asked him when he was at the CIA, ‘Director Pompeo, do you want to be Bill Casey?’” Dubowitz said, referring to Reagan’s CIA director. “I think he really put the agency on a much more aggressive footing with the Islamic republic.”

As an example of Pompeo’s ability as a diplomat on Iran, Dubowitz cited a speech Pompeo gave at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in July. In the speech, called “Supporting Iranian Voices,” Pompeo declared America’s backing for the Iranian opposition and condemned the regime in sweeping terms. Dubowitz likened the speech to Reagan’s historic 1982 address at Westminster, in which Reagan condemned the Soviet Union to the “ash heap of history.” He also pointed out that Anthony Dolan, the speechwriter who penned that line, is now on the staff of the NSC.

Pompeo did not respond to a request for comment. He has been a steadying figure in a turbulent administration, keeping Trump’s trust even as other officials have fallen out of favor. While at the CIA, he often delivered its daily briefings to the president personally. Like many conservatives, he adamantly opposed the nuclear deal on Capitol Hill, where a lack of support was one reason that Obama never asked Congress to ratify it as a treaty, signing it as an executive action instead. In a speech in May, Pompeo laid out 12 demands for changes in Iran’s behavior that covered, in addition to its nuclear program, topics such as ballistic missiles, support for proxy groups, assistance to rebels in Yemen, and the detention of US citizens. US officials cite these demands as the goal of their Iran policy. “Pompeo would do a deal,” Dubowitz said, if the right conditions were met.

Yet a former senior US official who was involved with Iran policy called the demands unrealistic. “In a way, they’re cynically setting out these demands fully aware that they’re never going to be met — that it’s just politically impossible for the current government of Iran to concede all of these points,” he said. “By setting goals that are unrealizable, that will make a clearer path to impose even harsher sanctions as a penalty for not complying with those 12 demands. And that economic pressure will bring about the end of the Islamic republic and its replacement with something more benign.”

The former official also worried that those seen as moderating influences on Iran policy — such as Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis — could see their voices weakened under a more aggressive US approach. The same scenario could play out in Iran as well. “In fact we’re strengthening the hands of people in Iran who advocate for a more confrontational approach, who would advocate for a greater willingness to use force against us,” the former official said. “And then of course once we get into that kind of downward spiral of threats and counter-threats, we have the same kind of dynamic going on here in Washington. It’s quite obvious that people who raise doubts about the wisdom of this policy are pretty much intimidated into staying silent about it. So thank goodness Mattis isn’t cowed by that. I think he’ll be arguing always for a more moderate response whenever possible. But his voice is increasingly lonely.”

Bolton’s approach to running the NSC makes his voice especially influential. While his predecessor, H.R. McMaster, emphasized interagency deliberations on key policy questions like Iran, Bolton considers himself less bureaucratic manager than Trump’s top adviser on foreign policy. “For complex issues like Iran, we need the NSC policymaking process to run well,” said Brewer, the former NSC official. “The process works best when the options going to the president are reflective of interagency deliberations rather than the recommendations of a single individual.”

One former US official who was involved in Iran policy under Trump said that those in the government who believe in a more moderate approach “have been operating in a culture of fear. And that has been the case since Day One — to the extent that people were very unwilling to talk on the phone with other colleagues in the government about certain things,” the official said. “Even on secure lines, we almost used to joke about it sometimes. It was like, ‘Oh, hello, whoever’s listening.’ Do I actually think that people were? I don’t know. Probably not. But there was a lot of concern.”

“If you’re using all elements of American power, have you thought through what happens when you do?”

This person added: “It really was just paranoia that was starting to set in, and we would have to have in-person meetings or meet for coffee, amongst our colleagues.”

Despite the chaos in the Trump administration, US officials have set about pushing through a series of longstanding conservative priorities, such as tax cuts and the appointment of Supreme Court justices. Roger Noriega, a former US ambassador and assistant secretary of state who is now a visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), said the same approach is taking shape in foreign policy. Noriega, who knows Bolton and Pompeo, said he’s a fan of Victory — he has an autographed copy and has shared the book with US policymakers — and believes it holds lessons for his own area of expertise, Latin America. He said that Pompeo, Bolton, and other members of Trump’s foreign policy team can operate despite the problems surrounding Trump. “While a lot of people who have joined the administration weren’t Trump stalwarts, we know that they’re serious people who are not going to be reined in by the president saying, ‘Hey, let me think about it, because I have to send some tweets,’” he said. “So I think it’s becoming a free-fire zone where they can try to take care of some of these [international] threats.”

Even within the FDD, though, there is some lingering concern. Jonathan Schanzer, the FDD’s senior vice president for research, summed up the administration’s policy this way: “Hammer them with everything, and potentially even collapse the regime.”

“The question I have about this book,” he said, tapping a copy of Victory, “is does the US have the chops to pull this off?”

He added, “If you’re using all elements of American power, have you thought through what happens when you do?”

III

During a recent visit to Washington, Schweizer, the author of Victory, who lives in Florida, said he was surprised to hear that his old book had received so much attention on the subject of Iran. While he has paid only casual attention to the debate over Iran policy in Washington, he said, he did notice some echoes of the Reagan era. As Reagan and his foreign policy team developed their own policy of maximum pressure, he noted, they couldn’t say for sure where it would lead. “This isn’t a science. It’s not like you can adjust the thermostat to the temperature you want,” he said. “If you say this is a strategy of maximum pressure, you just apply that pressure as much as you can and see what happens.”

In a recent article in Commentary, the scholar Frederick Kagan wrote a lengthy analysis of what he termed the “Victory Strategy” on Iran. The appeal, he wrote, “is obvious … the strategy produced the most desirable possible end of the Cold War — victory for the United States and its allies without a major direct conflict with the Soviet Union.” Kagan, a resident at AEI, where Bolton is a former senior fellow, wrote that elements of such a strategy could be successful in Iran if applied correctly and patiently.

But within Kagan’s analysis are somber warnings: Such a strategy, Kagan wrote, would need to be gradual and would likely take years to accomplish, possibly stretching beyond a Trump presidency. It could also require the US to look on as the Iranian regime cracked down on the opposition with ferocious violence. During the Cold War, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev first opened the door for democracy movements by allowing space for reform. Then, when pushed to the brink, he ultimately decided to step down rather than order the massacre of his opponents. In Iran, on the other hand, “It is almost impossible to imagine the current regime leadership losing the will to kill.”

US programs to support Iranian civil society and opposition groups were ongoing even under Obama, including efforts to help Iranians keep unfettered access to the internet through tools such as virtual private networks and encryption technology. These programs have become more concerted against the regime under Trump, said Mariam Memarsadeghi, an Iranian American who runs Tavaana, a State Department–funded program to promote civil society in Iran. She said that the Trump administration is more in tune with groups like hers that oppose the regime — and that concerns of what might happen if the regime were to collapse are misplaced. “I think Iran right now more than at any time since the revolution has the absorptive capacity to take whatever resources, rhetoric, and support the US can provide, and the US would be foolish not to take the opportunity,” she said. “Are there causes for concern? Yes, there are. But I’m sure that other countries that have made the transition from autocracy have had concerns as well.”

US programs to support Iranian civil society and opposition groups were ongoing under Obama. They've become more concerted under Trump.

Another source involved with US-backed democracy programs in Iran had found recent conversations with US officials alarming: “They’ve been reaching out to see how you can weaponize [the programs].”

Asked how, this person responded: “In theory? Create upheaval.”

The source noted that there are ways the US government could seek to exploit democracy promotion programs: helping to fund and organize demonstrations and boycotts, for example, or running social media campaigns intended to promote regime change.

“They’re trying to find something. They’re searching for things that you can do in the country,” this person said.

The former national security official involved in the corruption and sanctions project cautioned against the idea that any US government “can turn back the clock 50 years in six months.”

“It can backfire on you,” he said. “Or it contributes to mission creep.”

A retired senior intelligence official cautioned against misreading the likely impact of the protests, which he called a “rudderless” and “leaderless” movement that “just doesn’t threaten the regime.”

He added, “Anyone who believes that the Iranian regime is about to collapse is ignoring the data.”

He called sanctions “by their very nature, a long-term policy” and believed the Cold War frame could apply to Iran if policymakers are willing to be patient. Having worked with Pompeo during his time as CIA director, he said that while Pompeo espouses a tougher stance on Iran, he also takes the long view. “In many ways, the way to handle Iran benefits from using the approach we employed against the Soviets: Engage when possible, confront when we must,” he said. “I think there is a connection between then and now. But at the same time that’s long-term. And from what I know about Pompeo, he’s thinking long-term. His goal at the agency was to make the organization more responsive and robust, and he shows every sign of doing the same at State.”

IV

Yet the push for faster and more aggressive action on Iran continues.

Reuel Marc Gerecht, who worked on Iranian operations for the CIA in the 1980s and 1990s and is now a senior fellow at the FDD, promotes an even harder line than Dubowitz on Iran. (“Reuel thinks I’m a total wimp,” Dubowitz said.)

Gerecht and a co-author recently published an essay in the Weekly Standard calling on Trump and his foreign policy team to aggressively pursue a regime change strategy in Iran.

“The White House has all the elements of a regime change strategy despite its denials,” the authors wrote. “Post-Iraq, post-Afghanistan, the primary American question is whether Washington’s political elite is capable of imagining interventionism. A successful regime-change approach isn’t likely if one doesn’t really believe, as Reagan did, that American aid to those seeking freedom is both good and strategic.”

“The primary American question is whether Washington’s political elite is capable of imagining interventionism.”

But the Trump administration is restrained by what the authors call “an Iraq syndrome that argues against confronting Iranian imperialism with boots on the ground. It ought to be clear to Trump and his administration that regime change is the only pragmatic course open to them unless they are prepared to accept a nuclear-armed Iran. And if they are prepared for military action, they obviously should work seriously on advancing Iran’s internal rebellion.”

Asked about the reaction in the US government to the article, Gerecht replied: “There are those in the administration who really like it. There are those in the administration who are nervous about it.”

He added that one thing that could keep a lid on escalation between the US and Iran could be the Iranian regime itself, if it decides to wait out what it hopes will be a short-lived Trump administration, with the idea of dealing instead with its successor. “The only thing that deflates it — and it’s possible — is if the Iranians play a pretty cool game,” he said.

With that in mind, he suspected that Iranian leadership would be paying close attention to the political headwinds in the US midterm elections coming in November. “They don’t always analyze American politics well, but they do pay pretty close attention,” he said. •