DONETSK, Ukraine — Even the polling station officials who'd been working around the clock on the hastily organized referendum had to admit it: They had no idea what comes next.

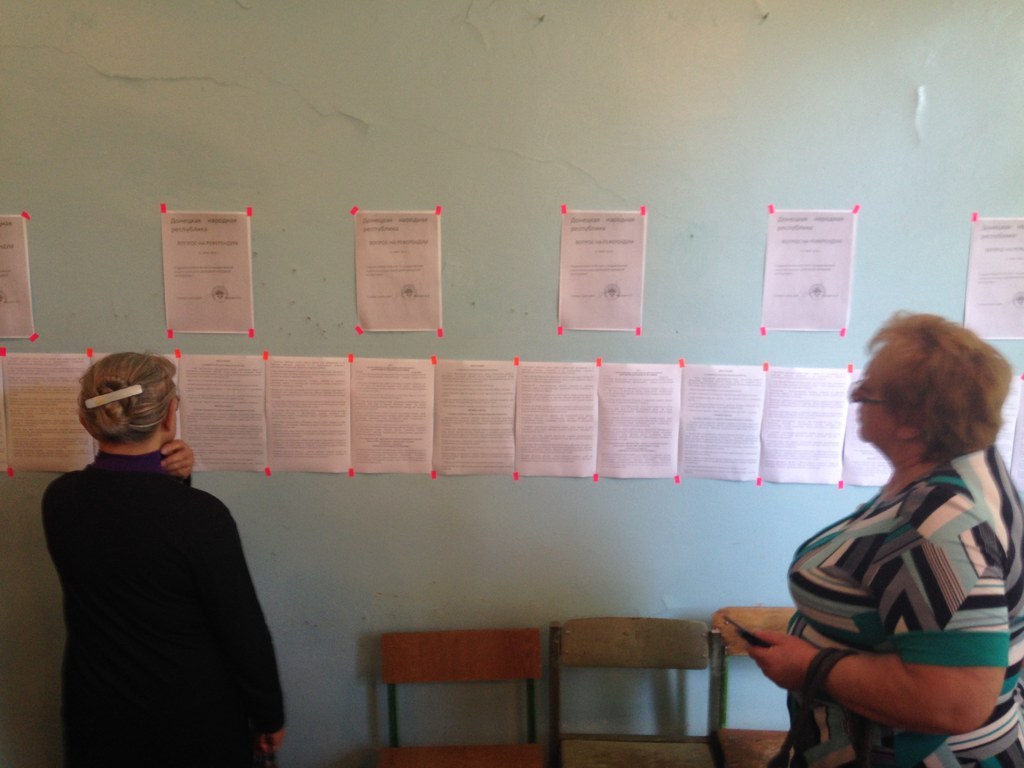

That the vote currently underway in some parts of eastern Ukraine would come down in favor of independence was not in doubt: Most opponents to the region's surging separatists would rather stay home than partake in a vote that they — along with the government in Kiev — see as a sham. But then what?

"That's a difficult question," said Andrei Zamliansky, an electrical engineer who was overseeing one crowded polling station in Donetsk.

He mentioned that local authorities, wary of confrontation, had more or less been letting the separatists in the city operate without too much trouble — and he seemed wary of any bloodshed that could result from a violent attempt by the separatists to seize more power. On the other hand, he wanted autonomy for the region — the subject of the single yes/no question on the ballot — and maybe to join Russia, following the example set by Crimea in March.

"It will be a long process," he said somewhat hopefully, echoing the sentiment of many in Donetsk on Sunday who seemed set on carrying out their referendum first, and thinking through the consequences later.

Polls consistently show that most voters in eastern Ukraine want to remain part of the country, a stark contrast to pre-referendum sentiment in Crimea. Yet the vote pressed ahead in the Donetsk region — which includes small cities such as Slovyansk and Mariupol that have seen heavy fighting between militants and Ukrainian forces — as well as in neighboring Luhansk.

Other important eastern and largely Russian-speaking regions, most notably Kharkiv, home to Ukraine's second-largest city, sat the referendum out.

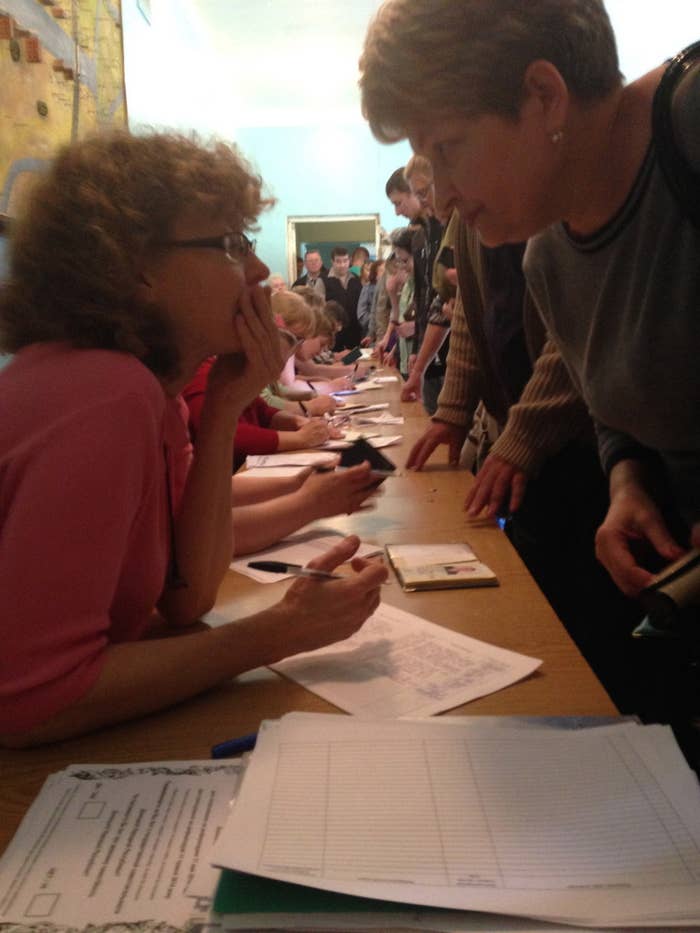

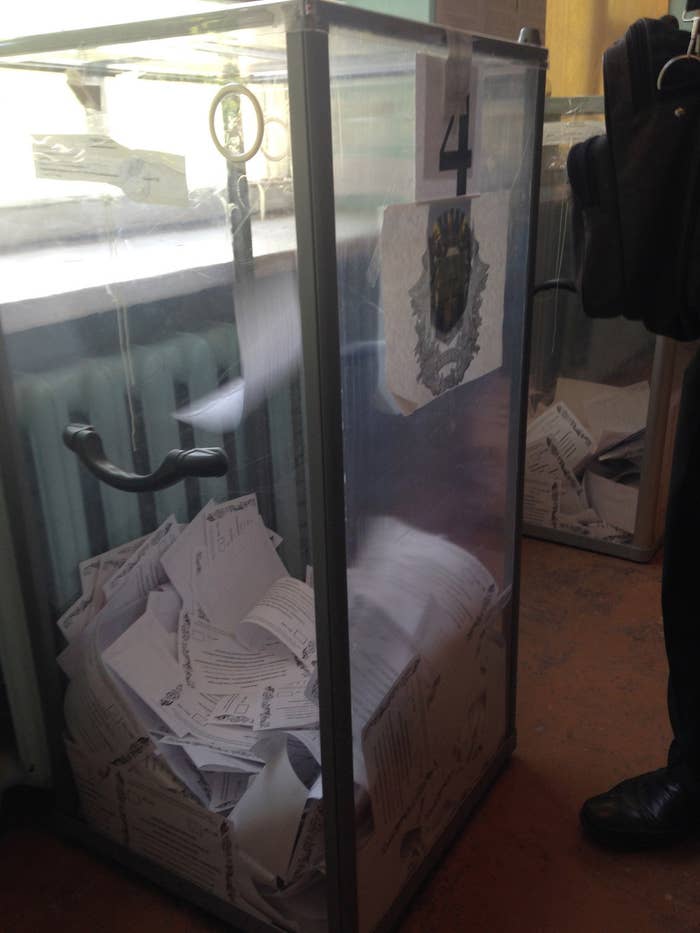

Turnout in Donetsk was strong enough to excite the poll's organizers, and at Zalmiansky's station, they earnestly urged this reporter to photograph the stretching line. Yet the lines there and elsewhere were partly a reflection of the fact that far fewer polling stations were up and running than in traditional votes.

By midday at the crowded station, Zalmiansky said he'd used about about half of his 5,000 ballots, and was worried he might run out. But the numbers on the ground were still a far cry from the figures being suggested by referendum leaders — who claimed in the early evening that in the Donetsk region, which has some five million residents, turnout had already exceeded 70%.

Partisans on both sides, in fact, seemed stuck on two competing extremes. As journalists such as C.J. Chivers of the New York Times noted while reporting from Slovyansk, turnout was "not insignificant." But even in Slovyansk, the rebel capital, it was still likely under 30%.

Both these true: 1. Referendum is farcical by any normal standard; 2. There is huge anti-Kiev and smaller but growing separatist sentiment.

Voting for Ukrainian citizens was held at polling stations in Russia too.

Wut MT @RT_com: Ukrainians in Moscow demonstrate passports as they take part in #referendum

At his polling station in Donetsk, Zalmiansky, looking weary with half of his button-down shirt untucked, was trying to make sure that the voting went as fairly and orderly as it could.

Despite reports from other polling stations that some people had brought in passports of those they wanted to vote on behalf of, or simply voted multiple times, he was organizing mobile election teams to visit those who were sick or otherwise couldn't make it to the poll.

And when a Russian woman insisted on casting a ballot — claiming that her father, also Russian, had been allowed to vote at another station — she was turned away, after a long and somewhat heated argument.

Yet even one pro-Russia activist in the city displayed some dark humor about the vote's integrity. Asked whether he'd cast a ballot, he replied: "Yes, and I voted for you too."

With much of the region overrun by pro-Russia militants, meanwhile, the sense of intimidation was evident even among those who'd ventured out to the polls. One man was seen casting what must have been one of the day's rare "no" votes on independence, but when interviewed just afterward, he lied and claimed that he'd checked "yes."

"For a new life," he said.

Inside a heavily guarded city building where referendum leaders had gathered on Sunday, meanwhile, they were busily preparing for the night's big press conference — almost certainly to announce their victory.

Andrei Porgin, one of Donetsk's top pro-Russia leaders, said a process of deliberation and negotiation would likely follow in the immediate aftermath of the referendum results. "Sovereignty means we have the right to decide what to do with this territory," he said with a smile. "We can choose to do whatever we want — we could even join Mars if we wanted."