Growing up, Erin Suh, a 20-year-old Korean American from Manhattan, remembers stressing about whether she was smart and quiet enough to fit into the “model minority” stereotypes she thought were expected of her.

Jadenne Radoc Cabahug, an 18-year-old Filipino American from Southern California, remembers wishing she were white.

Arin Siriamonthep, an 18-year-old Thai American from Greenvale, New York, remembers believing that the best way to deal with racist slurs or taunts was to “just let it go because there’s no need to cause some sort of argument.”

These three young people had always seen their country through the lens of watching their immigrant parents or grandparents settle into the US by working hard and striving to assimilate. But amid the racial justice protests and surge of hate crimes against Asian Americans in the last couple of years, Suh, Cabahug, and Siriamonthep have come to see the US’s problems more clearly, and they are now entering adulthood trying to figure out what they can do to help fix them while warding off the sense of helplessness caused by these converging crises.

During his senior year of high school, Siriamonthep founded a website where people could share their experiences navigating the country as Asian Americans. During her sophomore year of high school, Cabahug recorded an audio feature story for a public radio station about the racist discrimination that compelled her grandmother not to teach her Tagalog. As a sophomore in college, Suh started a TikTok account, @suhm.thoughts, devoted to social justice advocacy.

“I went through the same phases of having a lot of internalized racism, or being bigoted without doing so intentionally,” Suh said. “If I can help by sharing my own growth or sharing what I'm currently thinking about, I think that's one way I can contribute.”

She’d posted her first video, she said, “because I got frustrated with my lack of ability to do anything” during the week of protests following the police killing of George Floyd. In the 60-second clip, she argued against the use of tear gas by citing the 1925 Geneva Protocol banning chemical and biological weapons and provided practical tips for what to do if you’re exposed to it.

Her second and third videos denounced police training principles and police union rhetoric. Another pointed out how Asian and Black liberation movements are “inextricably linked” while calling out the anti-Black rhetoric she was seeing among some Asian communities. Within months, her videos were spreading to far more people than she’d expected, drawing more than 130,000 followers to her account and 6.1 million likes across her videos.

Her messages have resonated, she believes, because many others in her generation are going through a similar learning process.

“It was literally me dumping my thoughts onto the internet,” she said, “trying to come from a place of empathy, and recognizing that everyone starts somewhere, just like I started somewhere.”

For Cabahug, that starting point was an envy of whiteness that stemmed from witnessing the hardships her family members, especially her grandmother, had endured for being people of color who spoke their native tongue.

When Cabahug asked her grandmother why she had stopped teaching her Tagalog before she entered kindergarten, her grandmother said it was because the language was useless in the US. In fact, it was a liability: Cabahug’s grandmother recalled being barred from speaking anything but English at work, and Cabahug’s older cousin was placed into an English as a second language class because he sometimes mixed in Tagalog.

Cabahug began to reflect more on her heritage midway through high school, as she and her peers approached adulthood in a country where voices promoting white supremacist ideology seemed to be getting louder. She began studying Tagalog again and felt a newfound pride in navigating life as a woman of color. “There’s beauty in seeing that struggle,” she said.

Just as she’d come to embrace her cultural identity, the wave of attacks against Asian people brought horrific reminders of the threats that came with it. “To see people that look like you be hurt like this…takes a little part of your soul,” she said.

After noticing that white TikTok creators who post anime content weren’t saying anything about the attacks, Cabahug posted a tweet urging those who consume Asian media and products to not ignore the racism and instead stand in solidarity with Asian Americans. Her tweet received over 50,000 likes and more than 27,000 retweets.

“After the fact that people were getting called out, then they started to care,” she said. “The burden of social issues and oppression shouldn't have to fall on people of color.”

For young adults born in the internet age and locked indoors amid the tumult of the past year, online activism has been a natural outlet, though they recognize its limits. Cabahug said she aims to avoid the “performative” activism that makes broad claims of support without identifying specific avenues for change. In her video about tear gas, Suh acknowledged that she was aware that her words probably wouldn’t change policies, but she hoped to share the important information she was learning about the world.

“I constantly question myself: Is this something I just want [to do for] the approval and validation of others on the internet, or is it because I want to encourage discourse and make certain information more accessible?” Suh said.

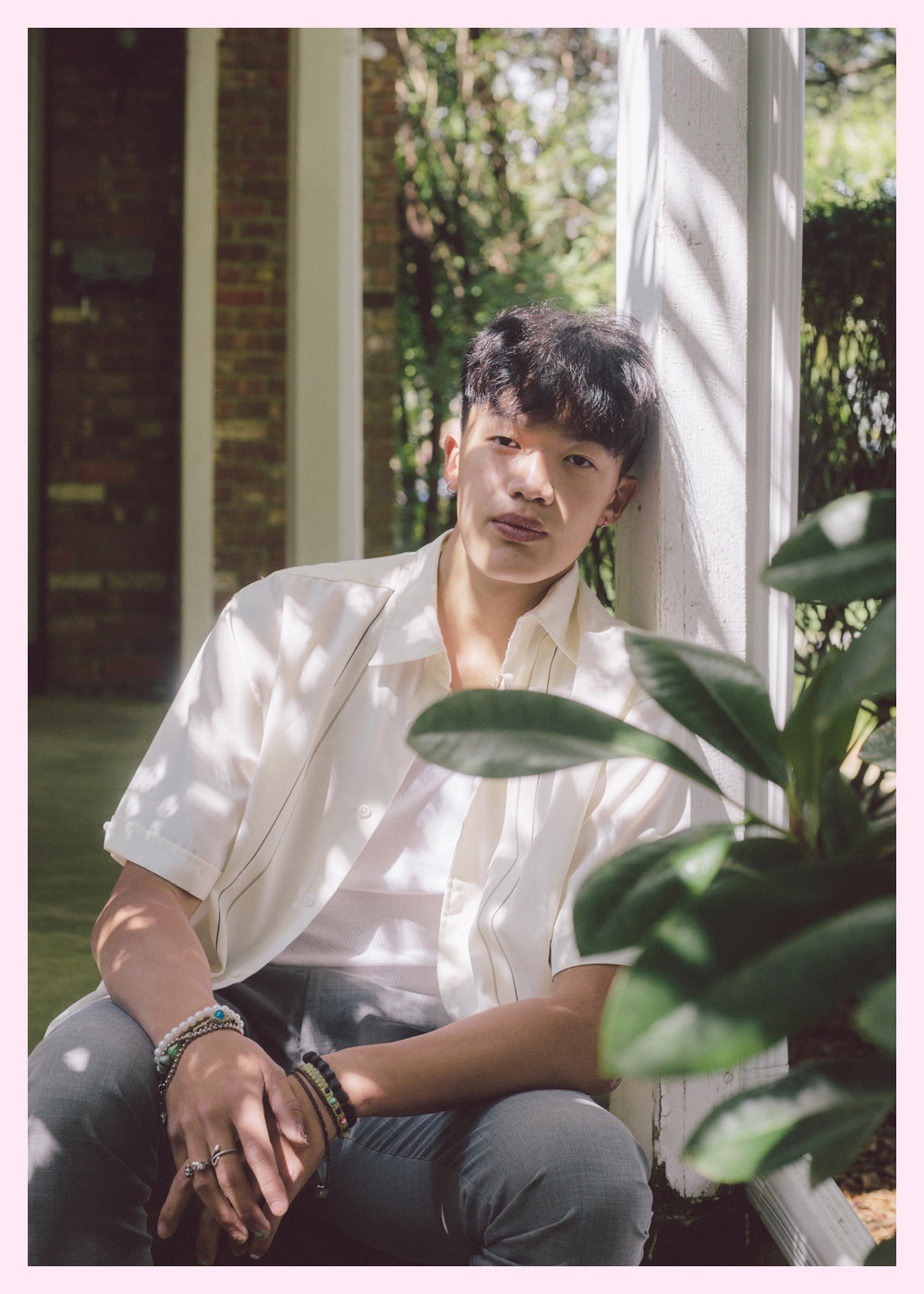

Like Suh, Siriamonthep also felt inspired by the protests last summer — he felt called to rally other Asian Americans to speak up about their experiences when he attended a Black Lives Matter march. At the protest, he ran to the front of the crowd and led a chant: “Say his name!” he shouted; “George Floyd!” the crowd replied. The sense of unity in the crowd was “one of the most beautiful things” he’d ever been a part of, he recalled.

Seeking to present the varied experiences of Asian diasporas as reports of racist violence cycled through the news, Siriamonthep founded Asians Speak Up, an organization where dozens of young people have shared stories about the pressure to assimilate and the challenges of reconnecting with their ancestral cultures.

His efforts to broadcast the struggles of American-raised Asian Gen Z’ers mark a sharp turn from the lessons he’d carried since childhood.

After arriving in New York from Thailand before he was born, his parents had lived in the attic of the restaurant their family owned. By the time of his earliest memories, their efforts had paid off: his parents had gone on to pursue an education in the US and eventually landed jobs in a hospital, affording them the opportunity to move into a big house located in a mostly upper-middle-class and white Long Island neighborhood, while his uncle took over the restaurant.

When he and his siblings faced racist taunts at school, his parents encouraged them to shake it off. “Because they’re immigrants, they’ve stayed quiet to incidents that may involve racism towards Asians, just because that’s how they were raised,” he said.

Unlike the young people submitting stories and photos to Siriamonthep’s website, his parents rarely talked about race. But then, in March, two days after the Atlanta spa shootings, his parents came to visit him at Boston University, where he was in his first year.

While at dinner, he was surprised to hear his parents for the first time talk about the attacks on Asian Americans. “Have you heard about the attacks in Georgia?” he recalled his father saying. “It’s everywhere.” Siriamonthep’s father only vaguely knew about Asians Speak Up until his mother reminded the family that night of their son’s efforts to make a positive impact on the lives of young Asian Americans.

For Siriamonthep, the conversation felt like an important turning point. His parents seemed to be reconsidering their old paradigms about how to respond to oppression in the US — which now included talking about it more openly as a family.

“I still had that mentality that the world was so big, and whatever I do is so minuscule,” Siriamonthep said. But seeing the shift in his parents was a milestone that filled him with optimism and a sense that “if you can put your mind to it, you can accomplish anything.”●