“I feel like I'm in a constant state of survival mode,” said Caitlin, 30, a third-grade public school teacher based in Texas, in a phone interview earlier this month. “The expectations for us are still very high.” Last April, Caitlin's district decided to conduct classes online. “I felt like that was the right move to make, because we really didn't know the severity of what was happening,” she told me. But after children had trouble logging into their classes and research emerged showing that adults typically experience the most severe cases of COVID-19, the district began following a hybrid model. Essentially, parents could have the option of choosing between sending their children back to school some days or continuing virtual classes.

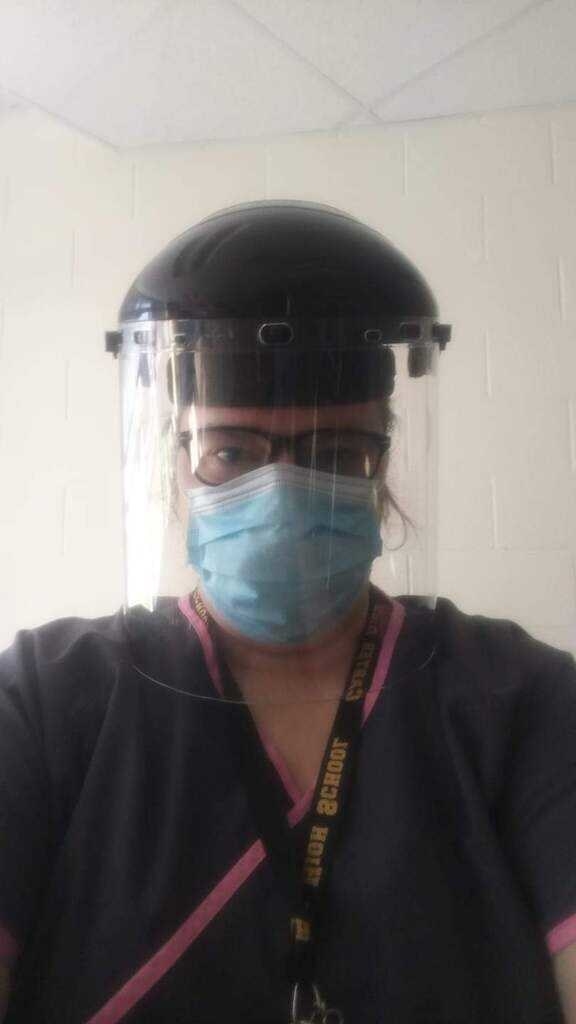

But while parents and students were given choices, Caitlin felt backed into a corner. “We're not given proper PPE, definitely no Clorox wipes to keep the place sanitary,” she said. “That comes out of our pocket, and it's hard to come by still.” Caitlin said her school’s administration promised teachers that their buildings would be properly sanitized. “We're trying to pick up a lot of slack for sanitation. And I don't feel like [administrators] held up their end of the bargain,” she added.

And although the CDC recently updated its guidelines to say that teachers could resume in-person learning because of the low transmission rates among children, Caitlin told me she believes the new guidance is not wholly sound.

“We're not given proper PPE, definitely no Clorox wipes to keep the place sanitary.”

Students in her district are required to wear masks, but this isn’t the case in a lot of Texas schools, where children under 10 are exempt in some areas. And Caitlin believes that some students at her school have gotten COVID-19, but she says there is no mandate for testing. Instead, students were given permission slips for parents to sign so that they could be tested at school for the virus, but most did not return the form, Caitlin said.

Caitlin is not alone in feeling deeply frustrated as a teacher right now. The chorus of voices — including aggressive parents — calling for schools to reopen across the country continues to grow. And there are legitimate reasons for wanting to do so: Virtual learning has been taxing, there’s great concern about what the pandemic has done to children’s mental health, and there are now updated guidelines from the CDC for how schools can safely reopen. Still, many educators are feeling undervalued and ignored.

BuzzFeed News recently asked teachers around the country to share their thoughts on reopening schools and how they are coping right now. Hundreds of teachers responded, revealing their uncertainty about the future, burnout, and frustration with parents, who they say look at them as glorified babysitters. Some teachers even expressed their desire to quit.

According to a New York Times story from January, no one knows exactly how many educators have died from COVID-19, but the confirmed death toll is at least 500. Molly, a 29-year-old ninth-grade English teacher who lives in Kissimmee, Florida, who asked that her last name be withheld, recently took out a significant life insurance policy after a local radio station advertised that educators could get them for free. For her, the stakes for reopening prematurely are crystal clear: “What we are discussing is what is the acceptable number of public school teachers to die.”

There was a time when Molly was all but certain that teaching, her dream job, would be a lifelong career. But that was before the pandemic, which has now killed more than 500,000 Americans. “I loved my job. I was good at my job. [Now] I cry most days and have never felt more incapable in my adult life.” She said she grapples with hearing about her students’ trauma while also having to deal with her own. “I talk to about 165 15-year-olds a day, and they're heavy. They are heavy little people right now. I mean, with such scary statistics coming out about self-harm [and] teen suicide. We become teachers because we care about our students so deeply. And I have had a hard time even allowing myself to fully process some of my stuff because I’m processing a lot of my students’ stuff.”

Some teachers said they feel like they have become stand-in public health officials, who have to make sure students are adhering to mask-wearing rules and other safety measures while hoping they can keep themselves — and their loved ones — safe.

“What we are discussing is what is the acceptable number of public school teachers to die.”

An art teacher in Dallas, who wanted to remain anonymous, described her morning routine. Upon waking up, she checks her temperature, and once she arrives at her school, she spends 30 minutes doing temperature checks for students and reminding them to wear masks. Then she does a headcount, sanitizes everyone’s hands, and finally begins teaching, starting with her kindergarteners, who “have no idea how to socially distance.”

Michelle McClendon, a 42-year-old teacher in Georgia, has had similar difficulties getting her students to comply with safety rules. “I believe my district has done a good job with our COVID precautions, but getting our students to follow them can be really challenging,” wrote McClendon. “We have to constantly tell them to spread out and pull their masks up.” McClendon added that there have been times when positive cases arise and “there are always a significant number of kids and often teachers that have to quarantine after exposure,” which means the school is short-staffed. “We get pulled to cover classes during our planning, and even the administrators have had to cover classes. Some schools in our district have had to shut down for a few days because they don’t have enough staff,” she said.

The consequences of not adhering to COVID-19 precautions can be life-threatening. Bonny Cannon, 43, who teaches agriculture at a specialized publicly funded high school for students with special needs, believes she contracted COVID-19 at work. Schools in North Carolina, where Cannon lives, closed last April in response to the pandemic, but Cannon’s school reopened for in-person learning on Nov. 2, according to the Winston-Salem Journal. (Other public high schools in the state resumed in early January.) Students at Cannon’s school aren’t required to wear masks, although the school suggests they do.

Cannon returned to in-person learning in early November, teaching four days a week, and recalled dealing with a maskless student who kept getting in her face. “I don't see how even people in regular schools are going to get everybody to wear a mask because if you can't get everybody to sit down when you tell them to sit down,” Cannon said. “If you can't get compliance on a regular day,” she trailed off. Shortly after, Cannon said she got an email about a possible exposure to the virus in her class, though the maskless student wasn’t the one who was sick.

Then, the week before Thanksgiving, during a time health experts predicted a surge in cases because of holiday travel, she began to feel sick, experiencing fatigue, chills, and body aches. Cannon also lost her sense of smell, but when she got tested for the coronavirus, the result came back negative. Her husband, who had diabetes and was disabled, became sick with all of the same symptoms Cannon had. He was admitted to the hospital on Nov. 28 and died on Dec. 9 of COVID-19 complications.

“There were times I felt like, essentially, I killed my husband. That's how you feel, but I've had to come to peace with it because I did the best that I could,” Cannon told me. “I did the best that I could, and I did what I had to do because we couldn't live without me going back to work.”

Cannon said she is certain she contracted the virus at school and subsequently gave it to her husband, as she only left the house for work or to go grocery shopping. She said she always wore a mask — even in her home — and would wash her hands and change her clothes after leaving work for home. But even while taking every precaution she could, there’s no way for her to definitively know how — or where — she may have contracted the virus.

“There's not a way to get a true number of the outbreaks that were truly school spread because the way that [administrators] look at exposures are not a true reflection,” Cannon said, speaking about the bigger implications of her false negative result. “I wanted to have a positive test so that my kids could be quarantined and my number could count on my school's dashboard,” Cannon said. (Cannon is not alone. There have been a number of reports of false negatives from faulty COVID-19 tests.) “My number will never count, and I wonder how many other people whose numbers don't count.”

“There were times I felt like, essentially, I killed my husband."

Meanwhile, as worries of contracting the virus continue, the actual work of teaching students has become more and more draining. Several teachers who responded to BuzzFeed News’ callout lamented how virtual learning has dampened their morale. “The best parts of teaching are in the students' faces. That look when they finally get it. Sharing a laugh over my dumb jokes. The furrowed brow when they're working through something complicated,” wrote Adam Rauscher, 41, who teaches in Dearborn, Michigan. “Right now, I teach to a sea of white letters on black boxes. I do the worst parts of teaching — grading and planning — without the best parts.”

Karli Boothe, 37, a third-grade ESL teacher based in Arlington, Virginia, who teaches roughly 80 students a day online, told me the biggest problem she faces some days is getting kids to answer the video call. “I text the parents and there's no response or it's ‘Oh, I'm at work. Let me check with the babysitter.’ So it doesn't matter what tools you give me if I can't get the child to answer the call.” If the call to parents is unsuccessful, Boothe then reaches out to the student’s homeroom teacher to see if their absence is a recurring pattern, at which point, an administrator or social worker will have to reach out to the parents. “Sometimes [reaching out for assistance] is helpful and sometimes it's not, because there's things happening — babysitters, lack of supervision — that make it difficult for the parents to enforce the child answering the call,” Boothe told me. “And then it's kind of like, again, everyone's trying their best. This is kind of what it is.”

What’s become apparent for teachers like Boothe is that the current setup will lead to “years of students having academic challenges.” Boothe told me that every year, third-graders are expected to make the leap from “learning to read to reading to learn. So instead of learning the mechanics of how to read, you now have to read information, get that information, and do something with it. And so that's a big change across the country that happens in third grade and that's hard to do every year. It's especially hard to do when we don't have physical books or we're not able to be physically with the kids.”

Boothe, who has been in her profession for a decade, said that having to relearn her job while being a “distanced, masked, 6-foot-away educator to a third of kids at a time” isn’t what she signed up for. “I love being an ESL teacher and watching students progress in their English knowledge, but I know that I can't keep doing this — what we're doing right now — because it's taking a toll on me,” she said.

Another teacher, who is based in Oregon and also wanted to remain anonymous, wrote, “Our administrators clearly only care about keeping our schools open to keep receiving tuition, and don’t care about the shortcuts and loopholes they have to take to do so.” At times, she said it has felt as though she is a first-year teacher again because of the workload. “I need time for self-care more than ever,” she said. “I’m spending my evenings and weekends lesson planning and grading, and it’s having a disastrous effect on my mental health. It’s just a matter of time before my coworkers and I hit full burnout. I’m not sure I can make it through the end of the school year at this rate.”

As teachers attempt to do their jobs in this new normal, there’s been a noticeable uptick in backlash against them from critics, including parents and folks in the media, who have called them lazy, selfish, among other things. Understandably, this has rubbed many teachers the wrong way.

“At first it was, ‘Oh we love our teachers’ and now it seems like people are sick of having their kids at home and want their babysitters back. They don’t appreciate that we are working even more hours than before planning our lessons remotely, checking in on missing students [and] dropping off supplies at their homes,” wrote Morgen Mayeda, a special education teacher in California.

“I am fairly concerned for the future of our profession and whether we are seen as educated professionals or dispensable babysitters,” wrote Jennica Olsen, 25, a former private school teacher in Washington state who taught elementary and middle schoolers and who now tutors after resigning due to concerns about her school’s reopening plan. Olsen said she has asthma, which is why she is especially concerned about getting COVID-19. After a confrontation with a parent who had an issue with her wearing a mask, she said she realized that “If I can't get parents to take it seriously, how am I going to encourage little people to keep a mask on all day, not touch each other, and wash their hands?”

And seeing insensitive posts from parents on social media has been difficult too. “Tell me why teachers can't go back in person when grocery store clerks have been working this whole time?” wrote Olsen, referring to a post she saw online. “Yet, there's no acknowledgement of the fact that grocery store clerks interact with customers for a fleeting moment behind a plexiglass shield, whereas we are in a small enclosed space for eight hours with kids who by nature, can't stay apart from each other.”

“The constant thing that we hear is: If we don't want to do this job, quit,” said Molly, the teacher based in Florida. “To my knowledge, I've not heard anyone saying that they don't want to do this job. We just don't want to die for it.” She added that the immense pressure being placed on educators especially in her state, where the Parkland shooting took place, has been happening for some time.

Though teachers are considered essential workers in most states, many educators have had trouble just getting an appointment to be vaccinated (which, to be fair, isn’t unique to them), and not all states have opened vaccine eligibility to teachers. According to Becky Pringle, president of the National Education Association, one of the country’s largest teachers unions, appeared on CNBC Wednesday saying almost half of all states still have not prioritized educators for the vaccine, which means that teachers as a specific group are not eligible to receive the vaccine as of yet.

Kara Penna, a high school teacher in New York, compared getting vaccinated to The Hunger Games. She has already received her first dose but said the process of getting the vaccine has been anything but straightforward for teachers.

Penna recalled colleagues using “bogus” links to sign up to receive vaccinations only to be turned away on the day of because it turned out they “didn’t have the appointments that they thought they had.” Penna wonders why the vaccine couldn’t just be administered at schools, where it would be easiest for teachers to receive them. While the CDC says teachers can go back to in-person learning without having had the vaccine, many teachers unions across the country insist educators should be vaccinated first before returning to school. The Biden administration has said it wants schools reopened within the president’s first 100 days in office, but the vaccine rollout has largely been left up to the states.

It’s likely that some teachers will leave the field because of how stressed they have become just trying to do their jobs. “I think about [quitting] every day, every day that I'm there,” Cailtin, the teacher from Texas, told me. “It would be really heartbreaking for me to have to leave and start over doing something else. The reason why I haven't really even considered it is because I don't know where to go next.”

Penna, who has been teaching for 25 years, told me, “People are looking to get out.” She noted how much harder it has become to hire substitute teachers. A woman in her department will go on maternity leave soon, and although the school posted a job for “a long-term sub through the end of the year for a month, we cannot get a single applicant because nobody wants to do subbing.” Part of the reason behind this could be because substitute teachers tend to be “older retirees” who may not have been yet vaccinated, she said. “So if they don't have to work, why would they risk that?”

“Constantly being told that you are the problem, that you're selfish, that you're ungrateful, that you could be replaced, that takes a toll,” said Boothe, the ESL teacher. She added that her job is one in which there is no space to be candid about how she and her colleagues across the country are struggling: “You always have to be on for the kids and act like everything's fine.” ●

UPDATE

The last name and photo of one of the people interviewed for this story have been removed at their request.