We were in the middle of having sex when D. said to me, “I want us to be official. I want to be your boyfriend.” The elation I felt — a warm sensation I remember so vividly — was tremendous, especially since we had only been seeing each other for about three months. Is this a decision you want to make while naked and horny? I thought to myself, but I pushed aside that fleeting moment of rational inquiry and replied, happily, “Yes. Of course I want to be your boyfriend too.”

D.’s unprompted admission that he wanted to be exclusive was a surprise to me because just days before, he’d expressed reservations about taking the relationship to the next level. Five weeks before he asked me to be his boyfriend, I’d had a major anxiety attack, stemming from a lack of sleep and unexpected, stressful travel. D. had gradually become the first person I’d speak to in the morning and the last person I’d talk to at night. He was someone I’d answer FaceTime calls for with no need for prior notice, and so I decided to open up about my various anxieties. He was becoming my person, and with the relationship going so well, I felt comfortable letting him in a bit more.

But, alas, my black gay romantic fairy tale was not meant to be — at least not with this guy.

While he calmed me down on the phone during that initial anxiety attack, I would later learn that this very human moment — where I expressed my worry that my depression and anxiety would ruin the good thing we had going — was something he couldn’t quite shake.

Alas, my black gay romantic fairy tale was not meant to be.

My explanations for why the anxiety attack occurred never seemed to be good enough, which in retrospect was a red flag. He once told me that we shouldn’t see each other until I’d spoken with my therapist — a blow to the heart, considering how intertwined we’d become. In my defense, it’s so much easier to rationalize and diminish why your needs aren’t being met when you’re falling for someone. As the exceptional animated series BoJack Horseman puts it, “When you look at someone through rose-colored glasses, all the red flags just look like flags.”

“I don’t think we’re a match,” D. told me, three days after he'd asked me to be his boyfriend while in bed. We were at the popular gay club Therapy, an ironic location in retrospect, since I had once asked him if he’d ever seen a therapist and he told me he had and had been informed that he was completely fine. We’d been having a date night, which I thought was going well. Earlier, we’d gone to Rockefeller Center, taken a photo by the tree (the picture was his suggestion), and gotten dinner before making our way to the club. I was stunned by D.'s comment and didn’t know how to respond, so I blurted out, “Who tells someone that they want to be with them, only to recant that statement three days later?”

Tears began to stream down my face, so I grabbed my coat and walked outside to get some air. After a few minutes in the freezing cold, I went back into the club and tried to talk to D., but he refused and suggested I go home and we’d talk about everything in the morning. I remember feeling devastated and crying in the Uber back to Brooklyn, wondering how the night had begun so perfectly and ended so poorly. And even though we hadn’t had a discussion about how to salvage the relationship — that would happen the following day — I knew in my heart that things were already over.

I had been through breakups before and was fairly comfortable being alone, but the abrupt ending of this relationship felt destabilizing in a new way. I could not think about anything or anyone other than D., how isolating it felt to be broken up with before we could celebrate the New Year’s Eve plans we had been excitedly texting about just days before. My appetite was nonexistent, showering felt like a chore, and going for a brief walk to get sunlight each day — which my therapist insisted on — felt impossible, mostly because I couldn’t help thinking that everyone I passed could clearly see the pain I was trying to camouflage.

Amid the unimaginable hurt I was feeling, I wondered how other people were navigating the often disappointing and demoralizing venture of dating. In search of answers, I set out to see how others stung by love — mostly millennials — were dealing with dating, breakups, and loneliness.

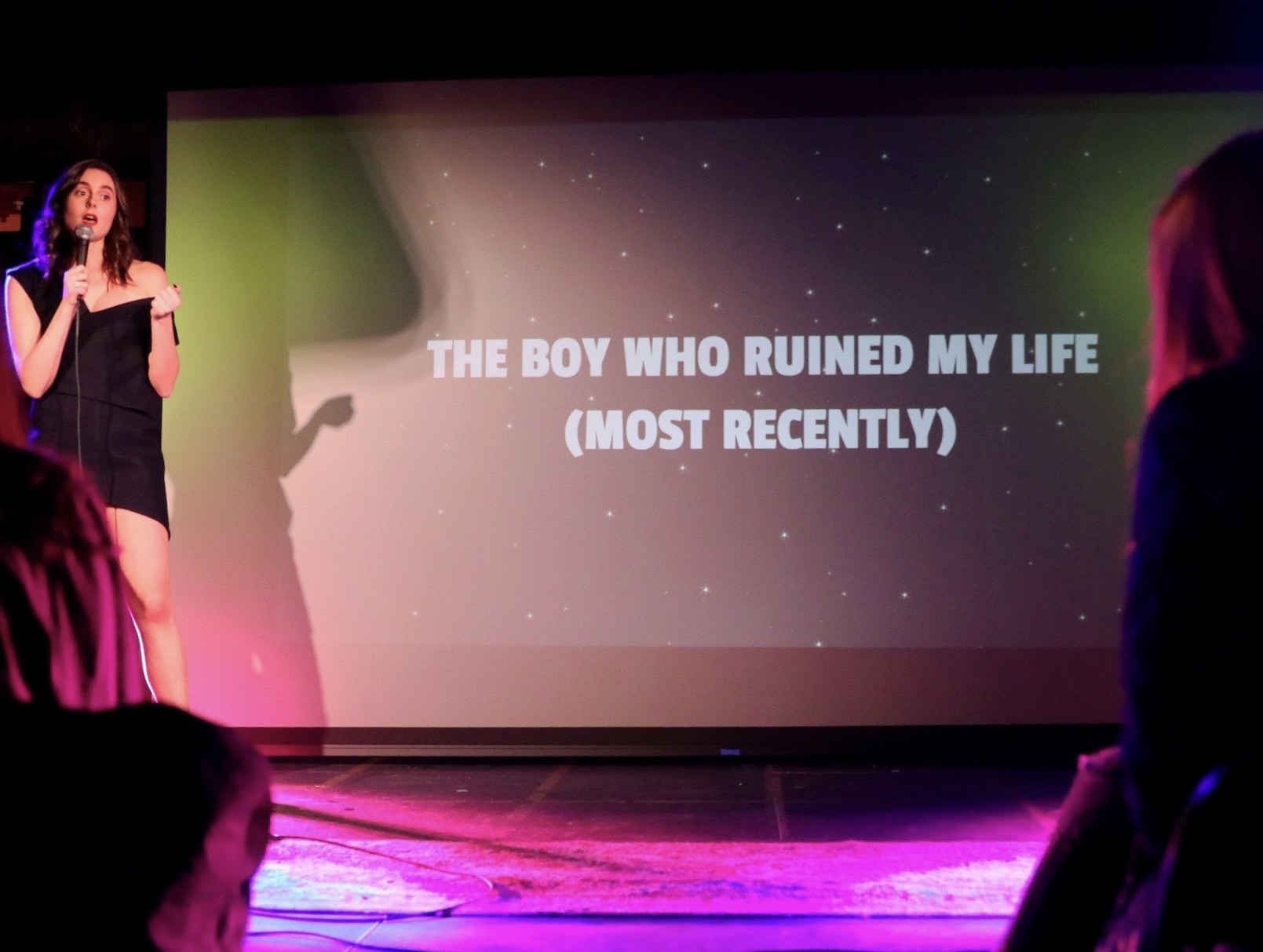

“I think we've gotten to a point where we're just taking what you can get, even if it’s not serving you really,” said Mary Beth Barone, 28, a New York–based comedian, improviser, and actor who hosts a comedy show called Drag His Ass: A Fuckboy Treatment Program.

“Like, I felt like the attention was really nice,” Barone told me in an interview after her sold-out show at the end of January, describing the ups and downs of a relationship with a recent fuckboy who’d occupied her attention. “And when things were good, they were good. And then when things were bad, it almost got to a point where I was like, Well, he's already hurt me so much; you can't hurt me more.”

Drag His Ass, held every three months and alternating between New York and Los Angeles, is a place where singles can come and laugh — or cry together — about dating, which Barone says seems to be going pretty poorly for everyone.

“I think we’ve gotten to a point where we’re just taking what you can get, even if it’s not serving you really.”

She got the idea for the show a year ago, after deciding to “start holding myself more accountable” by not going out with terrible guys. She even bought herself a whiteboard and began marking each day she successfully made it through fuckboy-free. Sometimes she would make it to 30 days and then would sleep with someone who turned out to be horrible. “And you can't always tell [that they are a fuckboy] before you sleep with them,” Barone joked, “which is the hard thing about it.” The goal was to make it to 100 days.

Last March, Barone posted that she’d finally completed 69 fuckboy-free days as a gag to her Instagram followers, and emboldened by the support she received, she decided to create a show. “I felt like a lot of my friends and especially comedians, because they're so open about everything, would have really relatable stories about dating and fuckboys,” Barone told me. “And just feeling like, What are we doing? Like, what does dating even look like right now?”

At each show, mostly packed with women attendees, a rotating roster of Barone’s comedian friends and acquaintances get onstage and regale the audience with stories about their dating train wrecks. At the end of each show, Barone tries to rehabilitate a fuckboy — which is a term the comedian said doesn’t apply to any specific gender — and her attempts have paid off in some instances.

During the show I attended, a woman named Alex Linde — who was emanating an aggressive devil-may-care sort of attitude — approached the stage and was questioned by Barone about her chaotic dating life. Barone began with a sampling of texts from guys who had once messaged Linde. "But I'm about to not answer my phone so if you show up I'm here if not okay,” Linde had messaged to a guy named Jon. “Alex. I'm literally in a car On my way to you rn. Keep your phone handy,” he said in a series of messages back. When Jon texted Linde that he was at the location, he received a reply that said: “wait, who is this lol.”

Throughout the evening, the audience nervously laughed at Linde’s bold approach to dating, which also included how she once had three different men she had dated or had just been casually talking to — and who were strangers to one another — help her move into an apartment. Toward the end of the conversation, Linde finally opened up about what caused her to treat with such disregard the men she comes into contact with, admitting that a former sexual partner in high school had given her a sexually transmitted infection, which had a significant impact on her. It’s unclear if Linde was transformed by the end of her rehabilitation, but the line of questioning definitely led to a better understanding of her seemingly detached way of dating.

“Do you have any hope for fuckboys?” I asked Barone after the show, to which she replied, “I do. Because a lot of the ones I've spoken to want to change, and I think they just don't know where to start.” Barone added that it’s “totally fine” for people who are in their early twenties to want to “fuck around and be crazy and irresponsible,” but the problem with a lot of fuckboys is that they’ve been stuck behaving this way for years. “How do you switch that off?” she said.

She gave me another example of a guy who had been a self-proclaimed fuckboy for years and found himself in the middle of an identity crisis once he fell in love with someone and entered a monogamous relationship with her. “He said he lost all sense of self because pursuing sex with women has been so rooted in his identity now for almost a decade,” Barone said of the guy, who eventually “freaked out and broke up” with the woman. “He was like, ‘I know I'm in love with her. I can’t commit.’” There was another man, named Tom, who messaged Barone after attending her show in August to let her know he’d ended things with two girls before sleeping with them because he “knew it wasn’t going anywhere.”

“And that, to me, was like, if it helps two people, that’s enough,” Barone said. “I know it sounds crazy to say that, but that’s why I want to do this.”

The thing about dating is that you often don’t know that someone is a fuckboy until after you’ve slept with them. When I think about my relationship with D., I have a hard time characterizing him completely as a fuckboy, especially when thinking about the glimpses of his personality that initially attracted me to him.

He’d been my neighborhood crush for a few months in the beginning of 2019 before we actually had a real conversation. Last May, he messaged me on the predominantly black gay hookup app Jack’d, and we made plans to go on a date, but when he didn’t take the initiative to choose a location to meet up, I decided I couldn’t be bothered and didn’t follow up. But later that fall, after coming to the conclusion that I wanted to date seriously and try a long-term relationship, I mustered up the courage to ask him out via the app and he said yes. We met at a bar in the East Village later that week, and it’s still one of my favorite first dates. He showed up a little late because of work, but I can still recall how he looked when he turned the corner and our eyes met. I remember instantly feeling at ease with him, which I credit to the copious amounts of alcohol we drank. And when he began to gently rub my left thigh, a sign that he was surely interested in more than just lighthearted conversation, it was clear to me that the night would likely end with us sleeping together.

We saw each other three times that first week of dating, which is honestly a lot for people living in New York City. Communication was fun and steady, never too much, never too little. We made time for each other, prioritized each other even though we had busy schedules, and for a while, that was enough. I began to fall for him because there was reciprocity, and for the most part he ticked all the boxes of what I wanted in a partner. I loved the way his eyes squinted when he laughed and when he flashed his dazzling smile; I loved the mesmerizing sway of his tiptoed gait, the random debates we’d have because he loved being playfully argumentative. And his dedication to helping black and brown children at an after-school program signaled to me that he valued community.

But while D. could be charming and delightful to be around, those positive attributes could disappear in a second, and I’d find myself on the receiving end of criticism that felt unfair. He would make cutting remarks about how I seemed “unstable” and was “too sensitive” and “emotional.” It often felt like he despised me for being aware of my emotions, and even more for wanting to talk about them. He said that he processed his emotions differently, but I didn’t understand why he needed to judge me for the ways in which I processed my own. When you’re dating someone and considering commitment, aren’t you supposed to want to talk to your partner about these things?

The thing about dating is that you often don’t know that someone is a fuckboy until after you’ve slept with them.

Thirty-four-year-old Donovan Thompson, a Brooklyn-based executive producer for The Grapevine, a YouTube series that gears its content to a young black audience, said he’s noticed that millennials tend to compartmentalize sex and intimacy. Because of the ability to quickly swipe left or right on potential partners on various dating apps, Thompson said, “you reduce the conversation of intimacy off the bat, based on just the physical, which is not necessarily the case when you meet someone live in person.”

Thompson is not alone in his assessment. In 2018, an Atlantic magazine story about how Tinder revolutionized the dating landscape noted how “the relative anonymity of dating apps—that is, the social disconnect between most people who match on them—has also made the dating landscape a ruder, flakier, crueler place.” That cruelty comes in many forms, including ghosting, which has become par for the course in a depersonalized dating landscape.

A New York Times story from September even highlighted how a number of IRL mixers like DateMyFriend.ppt, where folks in their twenties and thirties make slideshow presentations in an attempt to woo suitors for their friends, have started popping up to counteract the drudgery of online dating. It’s telling that one of the most discussed dating shows of the year so far is Netflix’s Love Is Blind — where singles who have been unlucky in finding love get to know potential partners by only listening to their voices — highlighting how fatigued people have become with the impersonality of dating.

Thompson said he believes that “social [media] has become a drug” and, in some ways, has made us more averse to wanting to fully commit to someone and more afraid of vulnerability. “There’s no opting out of an argument; there’s no ‘I’m just going to swipe off of this person.’ So then we’ve developed ghosting as a mechanism to protect us from the real-life awkwardness that we can’t escape.”

“We’ve developed ghosting as a mechanism to protect us from the real-life awkwardness that we can’t escape.”

Having some distance from your breakup undoubtedly brings clarity, and now, a couple of months later, I often think about how D. viewed me. Dealing with a 6-foot-1, large-framed black man who is open about his feelings can throw a lot of people, even men who date men. I often think my ex was drawn to me because of how I looked, and likely thrust his own beliefs on me about how I should act. But I think, as it became more apparent that I wasn’t just going to be some aloof person who was fine with surface-level conversations, he panicked. I often go back to our horrible argument the night before our breakup, where I asked him, “Why are you so upset with me just because I’m asking you how you’re feeling?” to which he responded, “Because you’re making me feel like a bitch!” Misogynistic undertones aside, the response hurt because it made me feel weird for being concerned about a person I felt I loved.

Before going over to D.’s place that morning for our final conversation, I stopped by the corner store to pick up two cups of coffee. I hated myself for knowing how he took his — black with two sugars, no cream. It was a reminder of what he seemed to dislike about me: that I cared too much.

I can still remember the look on his face when I entered his apartment: tired and sullen. I had a sinking feeling that there was something else weighing on him besides the fight that we’d had the previous night at Therapy. I petted his dog as we talked — running my fingers through the pup’s fur kept me at ease. D. kept going on about how he felt like I was guided by my emotions and that the way I reacted in the club was indicative of this. I countered by saying that I was hurt and there was no other way I could have responded, considering we’d been out all night — seemingly having fun — when he sprang this bombshell on me that he didn’t feel we were compatible, just days after saying he wanted me to be his boyfriend. Our conversation was going in circles when I asked him if there was anything else he needed to tell me. He said there was but that he didn’t feel like it would be helpful.

“Look, I’ve clearly indicated that there’s something on your mind. We’re having an open conversation, so just be out with it,” I said.

D. got up from his couch and moved over to his bed. I remember how drained and stripped of color his face looked as he lay down and finally told me what was on his mind.

He said that about 24 hours after telling me he wanted to be my boyfriend, while he was coming back home on a Friday night, he was complimented by a guy on the train who made a remark about the book he was reading, and he decided to sleep with him. He said he didn’t want to tell me because he knew I’d be hurt and because he vowed to himself that it wouldn’t happen again. I laughed upon hearing his revelation because it was comical that the person who so often tried to make the case that my mental health was unpredictable ended up being the one who was volatile.

But even with his admission of infidelity, I still had a hard time letting go at that moment. I joined him on his bed, lying by his side. Soon we were embracing, comforting each other in this agonizing moment. I remember him asking if I still wanted to make things work, and then in the next breath saying he actually didn’t want to make a determination right then. We talked about being in an open relationship, but it felt like his transgression was so out of left field that I wouldn’t be able to trust him ever again. I remember kissing his soft, full lips one last time and leaving the apartment, completely devastated.

In the hours and days after our breakup, it seemed like no matter what I tried to do, the crying wouldn’t cease. I couldn’t stop thinking whether there was something I could have done differently so our relationship could’ve been more successful. And even though I had the company of my roommate while dealing with this traumatic ordeal, I was overwhelmed by a sense of loneliness that felt debilitating.

“It’s better this happened now and not six months into the relationship,” my roommate told me. I could understand his remark on an intellectual level, but it did nothing to assuage feeling like I was inside a black hole, being ripped apart.

After the breakup, I couldn’t stand to be alone, which shocked me because I value my alone time. I’d stay on the phone for hours with friends who lived in other states, sometimes just sitting with them in silence because I just needed to feel a connection to someone. Even now, I worry that I overstay my welcome whenever I’m invited out because I don’t want to be alone, still feeling intensely sad.

But according to Josh Klapow, 51, a clinical psychologist who has spoken at length about the loneliness epidemic, “There is a big difference between being alone and being lonely.” Klapow added that “being lonely is a part of the human condition. We all get lonely. That's a normal experience.” Persistent or chronic loneliness, he said, is a problem that, when left untreated, can have major effects on an individual’s health, including depression and suicidal thoughts.

I knew the breakup had me feeling emotions that didn’t always make a lot of sense. I’d oscillate between sadness and anger, and then there’d be moments where I only thought about the good things D. did, like when he checked up on me and brought me tea when I was sick with strep throat. As someone who has depression, I tend to self-isolate, triggered by feeling alienated from everyone around me. With D. no longer in my life, I felt like a boat in the middle of the sea, unmoored and longing, desperately, for attachment, for comfort, for safety.

“He is not someone you needed in your life,” my friend Octavia, who once worked in the city but moved away last year to attend law school in North Carolina, said to me over the phone, right around the time when I was feeling the worst about the breakup. “Anyone who would do that to you clearly doesn’t care about you.” Our phone conversations were comforting because listening to her talk about her experiences with dating, especially as it related to being cheated on, helped me see that I wouldn’t always feel this way. Her last relationship was with a guy who cheated with another woman two years into their relationship. “It hurts, but I promise you will get through it,” she told me.

So why, even despite this, was D. the only person my brain kept telling me could fix my heartache? I began to have the crippling fear that I’d never find anyone to connect with. Klapow told me that having the foresight to make social plans ahead of time is important, specifically for someone like me, who has been plagued by feelings of loneliness post-breakup.

“If you want to not be lonely in life, you do not have to rely on romantic relationships to combat your loneliness.”

“You don’t like being alone; that’s okay,” Klapow told me. “Then you need a plan to address situations like this. Sometimes you can stay with friends and say nothing. You also [have to be] be honest and authentic,” he added, saying that I should let friends know about my feelings and offer to help them with an activity or plan an experience together. “You also can build in structure into your week so you identify those times when you feel particularly bad about being alone and again have a plan,” he said. Although this is helpful in the aftermath of a breakup, it can’t be used as a crutch forever. “It is important to learn to be comfortable alone. In the end, if you can’t self-soothe and be okay being alone, you will never fully be okay,” he added.

In the last year, most of my closest friends had moved out of New York to pursue graduate degrees in other states or take jobs on the other side of the country. In a bustling city where it seems like everyone else is constantly connecting and going out with friends and lovers, no longer being in close proximity with each other has been difficult, especially for simple things like asking a friend to dinner or a movie.

“If you want to not be lonely in life, you do not have to rely on romantic relationships to combat your loneliness,” Klapow told me. “You don’t even have to rely on longevity of a friendship; what you have to rely on is authentic connection.” When I asked him what alternatives there were, Klapow recommended going to a pet shelter, a senior center, or a church or community center where you can potentially form “meaningful human connections” as a way to combat loneliness. “The right person in your life could be somebody who's in a hospital you have a deep connection with who was a stranger you’ve come to know,” he said. “And I can't underscore how important that is, because we don't tend to go there naturally, particularly younger folks.”

So while my feeling of loneliness may not have been unusual following the breakup with D., being cognizant of the fact that I also have depression was important in making a distinction between feeling alone in the moment and pervasive loneliness. Since my experience with D., I’ve decided to take a hiatus from dating, mainly because I can’t seem to even drum up serious interest in anyone at the moment. I’m also very aware that I am not a person who is living in the world without a single soul to connect with, so I’m saying yes to as many social events as my introverted nature will allow. And while I can recognize when men are attractive, I don’t feel compelled to go up to anyone and strike up a conversation, and I haven’t had the courage to redownload any dating apps.

Thompson, the digital producer for The Grapevine, believes that the “compartmentalization” of emotions in the dating space “doesn’t give us the opportunity to work through our complex emotions,” which is essentially what a relationship is. “Because we don’t engage in pain, because we don’t engage in regular compromise, because once again we’re outfitted with so many options.”

“I think things will get worse before they get better,” Barone, the creator of Drag His Ass, told me. “But I do think they’ll get better.”

At heart, I’m also an optimist. And as I’ve continued working through my own breakup, I keep revisiting a moment D. and I had in early December, where we discussed bell hooks’ All About Love. One quote that has stuck with me goes, “When we understand love as the will to nurture our own and another's spiritual growth, it becomes clear that we cannot claim to love if we are hurtful and abusive. Love and abuse cannot coexist.” That night, after talking about our favorite parts of the book, we Ubered back to his apartment, his head in my lap. The thought of us cuddling that night is now just a warm memory to revisit every once in a while. But that’s all it was, because it wasn’t love. ●