Top U.S. commanders in Afghanistan waged a sophisticated public relations campaign to obscure horrific conditions at the Afghan National Military Hospital, according to former U.S. military officials, Congressional investigators, and new photographic evidence obtained by BuzzFeed.

The revelation is just one of the new details uncovered in a probe that has already triggered two Department of Defense investigations and one hearing by the House's Government Oversight Committee.

BuzzFeed obtained more than 70 images and over 120 field reports and documents that further implicate the command of Gen. William Caldwell in the scandal.

At the time, Caldwell was in charge of NTM-A, or National Training Mission Afghanistan, the $11.2 billion a year program, which included the Dawood National Military Hospital.

"There were glowing stories on NTM-A’s public relations web site about the progress of the [Afghan National Army] medical system," Col. Gerald Carozza, a senior Army lawyer, testified. "With conditions not changing from 2005 to 2010, why did the assessment and public relations reporting show improvement though early 2010 when the reality was clearly different?"

The new information also reveals fresh evidence of neglect at the hospital, possible corruption perpetrated by private Pentagon contractor MPRI, and allegations that top Afghan general Ahmed Yaftali sold 4.5 tons of U.S-purchased medical supplies to Pakistan and embezzled some $20 million in U.S. taxpayer dollars provided to the hospital.

Other documents obtained by BuzzFeed include new details on the Pentagon's efforts to stonewall the investigation — including attempts to keep key details from Congress and efforts to make witnesses unavailable to testify.

Caldwell, now commander of U.S. Army North, has not yet been called before Congress, but a spokesperson for Caldwell has said "all allegations will be proven false."

The images below show the striking contrast between what the U.S. military command in Kabul wanted American audiences to know and the much darker reality of the Dawood National Military Hospital.

March 2010.

"Although the hospital is still undermanned, patient care has improved with the help of additional equipment and capabilities," reads the official U.S. military photo description from early 2010.

When senior U.S. officials and dignitaries visited the National Military Hospital, they were given what Col. Geller called "the dog and pony show" or "the wet mop tour."

In this tour photo, a patient's leg is healing well, and the dressings on his leg brace are clean.

But behind the "dog and pony show" were medical conditions that Gen. Caldwell and his command did not want public. For example, this patient was not getting proper care for a gangrenous foot.

This Afghan National Policeman spent 40 days at Dawood following an ambush.

He suffered from malnutrition, lost 50 pounds while at the hospital, and had an untreated decubitis ulcer on the back of his head.

A second patient experienced malnutrition and starvation while at the hospital.

Here is Gen. Caldwell at the hospital visiting with Gen. Yaftali. Yaftali provided at least 4.5 tons of U.S.-supplied pharmaceuticals to Pakistan as part of a "criminal patronage network."

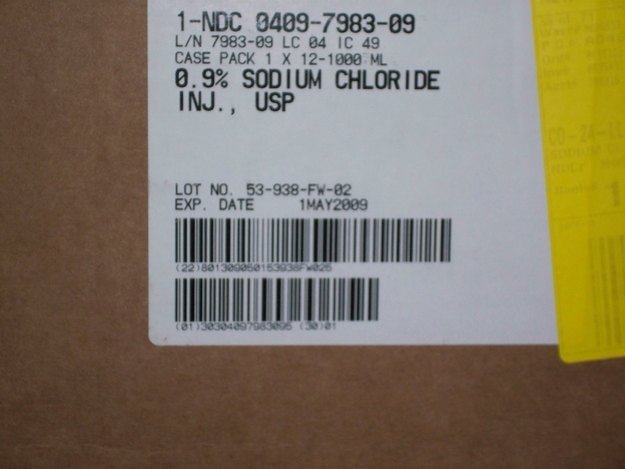

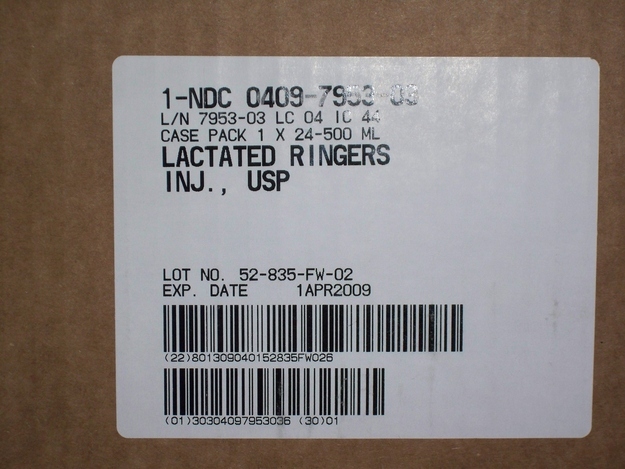

These medical supplies were provided to the Afghan hospital. The photos were taken on March 13, 2010.

Expiration date: April 1, 2009.

A warehouse of expired medical supplies.

The following photos were included in a presentation to Gen. Caldwell and his command in early November, 2010. After seeing the presentation, Caldwell's command ordered the documents to be sequestered."[Caldwell] didn't want this getting out to an

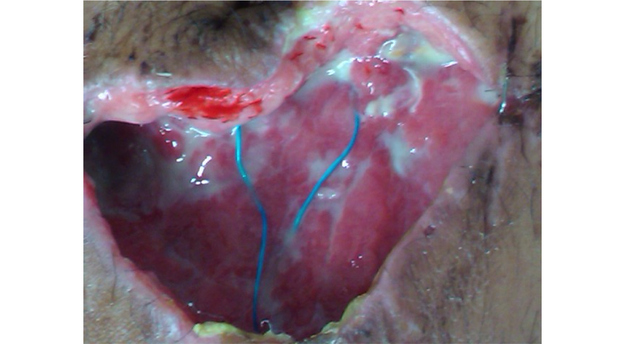

This man's right leg was amputated. As part of the healing process, the dressings on his wound needed to be changed regularly. Doctors failed to do so.

When his wounds were cleaned, it was in an unsterile environment, with the patient's family members touching the wound with ungloved hands. Doctors also re-used medical equipment, citing insufficient sterilization supplies.

Doctors never gave this patient pain medication.

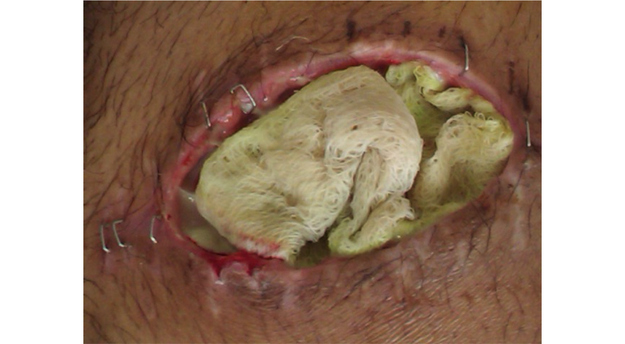

Another man's amputated leg was cleaned in the same room, which was not cleaned between patients. The hospital went without cleaning supplies for five months.

This man was the victim of an IED detonation. His left eye had to be removed.

He remained in the National Military Hospital for three and a half months after being admitted into the wrong department.

An eye globe prosthesis was inserted in place of his missing eye. It was positioned incorrectly for three months.

The eye socket then became severely infected.

This man was shot in the abdomen in Kandahar, a southern province in Afghanistan.

He was originally treated in one of Afghanistan's regional hospitals, then transferred to the National Military Hospital.

His wounds remained uncovered for three hours each day, leaving them to be exposed to sunlight and flies.

When nurses cleaned the man's deep wounds, they did so without administering pain medication.

The patient was not placed on antibiotics.

This 16-year-old was admitted to the NMH a few days after he underwent intestinal surgery to repair his duodenum. He also had a leg injury.

When doctors did their rounds, they noted that the boy was in good condition with strong vitals.

A mentor removed a dressing on the boy's leg, revealing inches of bone exposed through the patient's skin. Orthopedics would not treat him because they didn't have sufficient beds.

At the end of Nov. 2010, U.S. medical personnel were still under command pressure to portray the hospital in a positive light. "We were always being asked to find the good news to report even in a terrible story," said Col. Geller of the presentation.

After U.S. medical personnel demanded an investigation of the hospital in the fall of 2010, Gen. Caldwell refused, saying: "There is nothing wrong in this command we can't fix ourselves."

Caldwell also said senior officers "should have known better" than to ask for the investigation.

Col. Gerald Carozza would later testify that Caldwell "was too concerned about the message, creating a stifling climate for those who had to deal with reality."

In October 2011, Congress opened an investigation into the hospital. They submitted a request to the DoD, asking for a detailed timeline of the events that took place at Dawood, among other documents.

Col. Geller provided this information to the DoD, but the DoD withheld key facts from Congress that Geller had given them. These included information about Caldwell's role, the role of private contractor MPRI, and Gen. Yaftali's involvement in a criminal patronage network.

When Congress called Col. Fassl and Capt. Steven Andersen to testify in the July 24 hearing, the DoD and Dept. of Homeland Security told investigators that neither officer would be able to appear. Congress then had to threaten both Col. Fassl and Capt. Andersen with a subpoena.

Fassl's subsequent testimony was damning. At the hospital, one could see "open baths of blood draining out of soldiers' wounds, the feces on the floor," Fassl said.