May 2014, a month after I published my first article about being trans, I woke up at dawn between two naked men, on the top floor of a townhouse in Park Slope. I’d followed the rules of straight womanhood for over a decade, and it hadn’t made me happy, so I wanted to test my boundaries, push myself to be with people in ways I hadn’t before. That was when Barrett and Jason came along, a bisexual couple I met online who were interested in dating a woman.

I turned on my side to face Barrett, the one with whom I felt a stronger romantic attachment; Jason felt more like a friend I enjoyed having sex with. Bald and a decade older than me, Barrett had left his own rural upbringing in Alabama to become a modern dancer and interactive artist in New York, which led to a career as a digital consultant and allowed him to unexpectedly come into wealth. He and Jason didn’t know I was trans when we first met, but I sent them one of my articles and, as I had hoped, they treated my gender as a nonissue.

Barrett opened his eyes and smiled. I could tell they were hazel but not much else, though I’d examined plenty of close‑up eye pictures before, and filled in details with my mind — dark rings around his irises, dilated pupils because of the dim dawn light and, maybe a little bit, his attraction to me. He tilted his head to indicate that we should leave the room together, and I followed him down a set of wooden stairs with steel pipes for rails, part of this couple’s industrial aesthetic in a house they designed and renovated themselves.

“I’ll get us some coffee,” he whispered as he proceeded to the kitchen on the ground floor while I stayed on the second, an open area lined with bookshelves, a peacock-green velvet couch on one side and a mid-century dining table on the other. Off that big room was a smaller room they used for guests. I noticed that the door was open, so I went inside.

I knew by “woman” he meant “white woman.” I wanted to be pleased but was surprised at myself that I wasn’t.

Barrett and Jason also used the room as a walk‑in closet; I noticed a shelf of stylish shoes on one side and suits on wooden hangers. On another end of the room was a giant mirror, framed in ornate gold leaf, leaning against the wall. I stood in front of it and looked at myself, as morning light illuminated my body, and recalled how comfortable I’d been walking around nude in Barrett’s presence. It was a relief to feel safe without clothes in front of some one else, after years of asking men to turn lights off, for fear they would find something overly masculine about my body, my too-slim hips, my muscular shoulders and back from years of lifting weights, a fear that did not go away even when men admired that body for being powerful and athletic.

“Admiring yourself again?” Barrett asked as he poked his head into the room, then went in to stand behind me. “I’m sure it feels great to be almost forty and have the breasts of a teenager.” I laughed, not just at the joke but at the openness of our relationship. The past decade when I decided to be private about my transition except to those I was closest to, the men I’d been involved with had accepted my history as fact but had also been all too willing to deny its reality, something never to be discussed again once revealed. Though really, I was more responsible for this than they were, because their reticence was an echo of my own shame, my silence like trying to suffocate my history by refusing to breathe. It was such a relief to exhale. “It’s funny,” Barrett continued as he stared at my reflection. “I know you’re trans, but I can’t really tell. It’s a lot harder to see you were an Asian man when I can’t see you as Asian to begin with. To me you’re just a woman with a dancer’s body.” I nodded. I knew by “woman” he meant “white woman.” I wanted to be pleased but was surprised at myself that I wasn’t.

We left the room and had coffee at the dining table, but Barrett’s words kept playing in my head, “I don’t see you as trans,” coupled with “I can’t tell you’re Asian.” The way he looked at me was exactly what I’d honed over many years, this trick of perception, and it puzzled me that I was dissatisfied over having accomplished it, a state of being so many trans women sacrifice so much to achieve. Maybe I didn’t feel the satisfaction because I hadn’t sacrificed enough, only had reassignment surgery, hadn’t touched my face or gotten implants. Though remaining undisclosed for a decade was burden enough, so it wasn’t that. It was something about how my gender and race reflected on each other like a dizzying hall of distorted mirrors.

When people looked at me and only saw a white person, I understood that being white wasn’t actually better, that I only coveted whiteness because of what I associated it with — wealth, education, and beauty. But for someone like me, whose whiteness was literally skin deep, who did not have any meaningful European ancestry, to be perceived as white could only mean that whiteness is nothing more than illusion. In an ideal world, I wouldn’t need to go through so much effort, make so many sacrifices to gain the privileges of whiteness, and other brown people who are not albino would have just as much access to those privileges if they wanted it.

To become a woman in the world’s eyes, I made what felt like a huge sacrifice at the time, but in hindsight was really a cosmetic change not unlike a nose job.

I flinched when Barrett told me he only saw me as a woman, because my experience with race forced me to understand that womanhood wasn’t real either. I wanted to be a woman because I wanted other people to perceive my qualities through the lens of that gender, but having molded myself to their expectations, I now understood how much of an illusion gender was too. To become a woman in the world’s eyes, I made what felt like a huge sacrifice at the time, reassignment surgery, but in hindsight was really a cosmetic change not unlike a nose job, a shift in a body part’s aesthetic appearance while keeping its function intact — the only difference was the meaning our society invested in one body part versus the other.

Had I lived in a world where men were allowed to dress and behave like women without being scorned or punished, I wouldn’t have needed to be a woman at all. Over the following months, I grew alienated from Barrett and eventually stopped dating him, not because he did anything terrible but I just didn’t want to see myself through his eyes. I came to understand that what I wanted was to be seen as my complete self — my gender, my race, my history — without being judged because of it. I wanted people close to me to see an albino person who had learned how to look and act white so the world would more readily accept her, and understand how that had been a key part of her survival. I wanted people to see how that albino person was also transgender, and that she transitioned to be able to express her femininity and had surgery so she would be perceived as being like any other woman, her qualities appreciated on those terms. And if she ever hid who she actually was, it was only so that she could be granted entrance into worlds she couldn’t otherwise reach, worlds that should rightfully belong to everyone, not just those who happen to uphold the prevailing standards of whiteness and womanhood.●

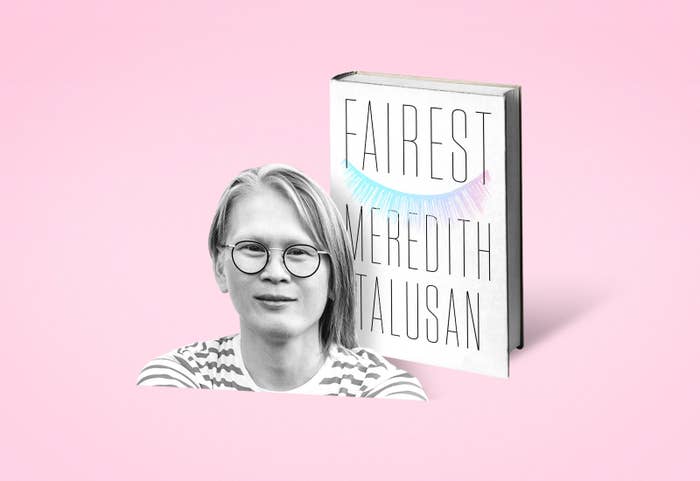

From FAIREST by Meredith Talusan, to be published on May 26, 2020 by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2020 by Meredith Talusan.

Meredith Talusan is an award-winning author and journalist who has written for the Guardian, the New York Times, the Atlantic, the Nation, WIRED, SELF, and Condé Nast Traveler, among many other publications, and has contributed to several essay collections. She has received awards from GLAAD, the Society of Professional Journalists, and the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association. She is also the founding executive editor of them., Condé Nast’s LGBTQ+ digital platform, where she is currently contributing editor.