The parking lot is dark. The blonde woman — alone — pushes her grocery cart toward her car. “Crime is out of control,” a shaky-voiced narrator warns as the woman’s white knuckles cling to the cart. “It drives the fear that we will feel. Pumping gas. Walking to the car.”

Then the camera cuts to the Republican candidate for New Mexico governor, Mark Ronchetti, who helps the woman unload her groceries as he announces his plans for combating crime.

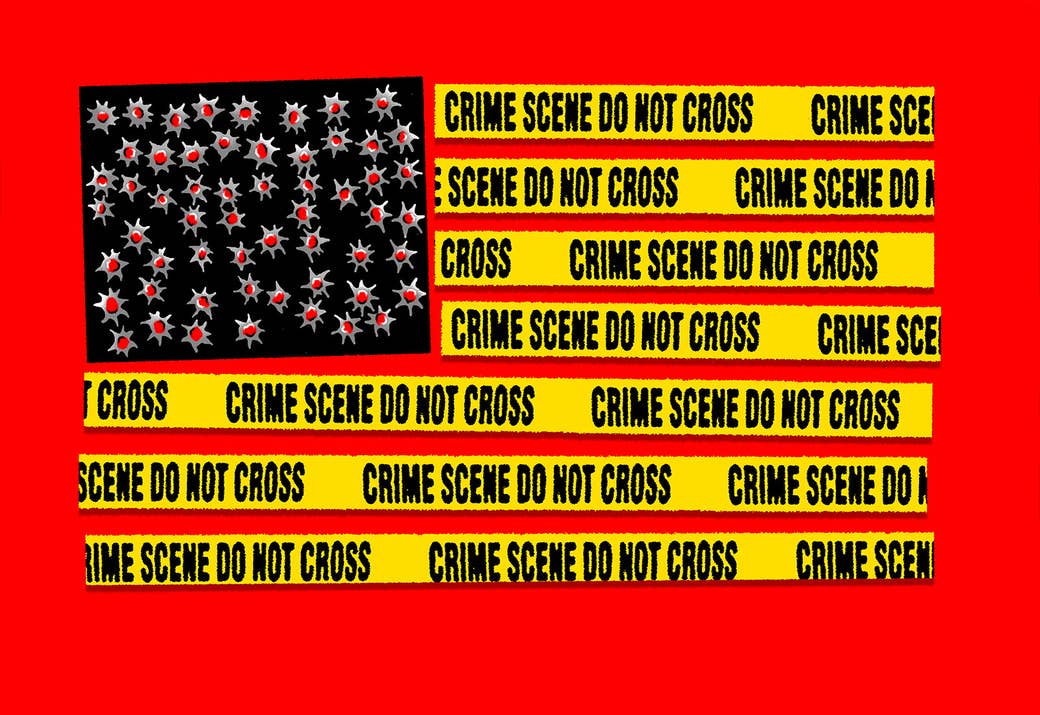

Throw a dart at a map of the United States, and it’s likely you’ll hit a place where campaigns are airing similar ads with ominous undertones and reports of terrifying violence.

In New York, the Republican candidate for governor is running a video so graphic that its images of people being gunned down on sidewalks come with an age restriction and content warning on YouTube. The video closes with the tagline “Vote like your life depends on it. It just might.”

An ad in Wisconsin in support of reelecting Republican Sen. Ron Johnson shows clips of an SUV plowing through a holiday parade last year, warning voters of the perils of voting for his Democratic opponent Lt. Gov. Mandela Barnes, whom the ad alleges has ties to a group that wants to “defund the police.” (Barnes’s campaign countered those claims with its own ad saying he does not support defunding police.)

But the shocking images and haunting voices in the ads — which Republicans have reportedly spent more than $21 million on over the last two weeks of September, to make crime a central issue in midterm elections — aren’t what send a chill down the spines of some crime researchers. It’s the misinformation they spout.

“As a matter of making communities safer, no one benefits from false or overblown crime narratives,” Insha Rahman, vice president of advocacy and partnerships at the Vera Institute for Justice, told BuzzFeed News in an email. “Elected officials and politicians are accountable for spending resources and enacting policies that truly address the drivers of crime and violence and are not simply props for a media moment or a political wins.”

That Republicans have decided to focus on crime during the homestretch of the upcoming midterm elections is neither new nor surprising. It’s been part of the conservative political playbook since the days of Richard Nixon, who popularized the phrase “law and order,” and the messaging has stuck. A recent ABC News/Washington Post poll found that 56% of registered voters trust Republicans more than Democrats to deal with crime.

But while Republicans are blaming Democrats for the recent spike in crime — murders were up 30% in 2020 — experts who study the data say it’s not that simple. 2020 did bring more violence, and it coincided with the pandemic and a variety of policies seeking to reform policing following the death of George Floyd. But don’t forget that old college rule: Correlation isn’t necessarily causation. Just because two things happen at the same time doesn’t mean one causes the other. And what the Republican ads leave out is that both red and blue jurisdictions — rural and urban — saw increases in crime.

BuzzFeed News spoke with crime policy experts to separate the campaign slogans from the research-backed solutions. Here’s what they told us:

Ad assumption: More police, fewer crimes

The line appears in ads across the country. “[Insert Candidate Name Here] supports defunding the police.” Some flashing emergency lights and images of yellow crime tape frequently appear in the background as Candidate X details all the ways Candidate Y will strip away police.

While it might be effective rhetoric, it’s without empirical evidence. Even in jurisdictions where elected officials expressed concern about police budgets — the police department is often the single-biggest ticket item in a city’s budget — spending on police has trended up, not down, in recent years.

Which raises another question: If police budgets have increased in tandem with violent crime, do more officers actually mean fewer crimes?

A recent study by NYU economist Morgan Williams found that adding one new police officer to a city prevents 0.06 to 0.1 homicides per year. In other words, Williams found that a city would need to hire 10 to 17 more officers to save one life annually. Adding those officers increases city budgets between $1.3 to 2.2 million, Williams showed.

Rahman of the Vera Institute added that the impact of putting more officers on the street isn’t evenly felt across communities.

“Those potential benefits decrease significantly in predominately Black or brown cities and neighborhoods, where more police presence has been shown to increase low-level arrests and more negative interactions between police and community members,” she said.

Meanwhile, alternatives to traditional policing have had a real impact. The CAHOOTS program in Eugene, Oregon, which dispatches civilian responders to crisis calls, has saved an estimated $14 million annually in emergency room visits and ambulance costs, on top of an estimated $8.5 million in other public safety expenditures.

The implementation of violence intervention program Cure Violence, under which trusted community members mediate and de-escalate tensions, has seen shootings drop 30% in some neighborhoods of Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia. Organizers estimate they’re saving taxpayers $18 for every dollar invested in the program.

Something else that’s been proven to reduce crime? Installing streetlights, or simply ensuring existing ones work.

Ad assumption: Blame bail reform

As New Mexico’s Ronchetti unloads the blonde woman’s grocery cart in his ad, he vows to end “catch and release.” Other ads use the phrase “end the revolving door.” All mean the same thing: End bail reforms.

From New Mexico to New York, the specific details of bail reform vary, but the central aim is the same: Ensure people waiting for their day in court aren’t behind bars simply because they can’t afford bond.

Ads like this one from Rep. Lee Zeldin, who’s running for New York governor, and Ronchetti’s suggest that these efforts create a system where people are arrested, charged, then released, only to be arrested again, charged, and released again.

But the numbers don’t support that narrative.

A research paper from think tank the Santa Fe Institute in collaboration with researchers from the University of New Mexico found that only 3% of people who were released to await their day in court committed a new violent felony. The researchers found that 1,000 people would have to be locked up to prevent one person from committing a first-degree felony.

Research in other states is also finding that reducing the number of people in jail awaiting trial isn’t behind their respective crime increases either.

Ames Grawert of NYU’s Brennan Center for Justice told BuzzFeed News that early data out of New York doesn’t support bail reform leading to more crime.

“These sorts of narratives that look for convenient single actors to blame, I think are deeply frustrating to me and a disservice to a really complicated topic,” Grawert said. He added that even decades after the great crime decline of the 1990s, researchers still can’t be totally certain what caused it.

“When we talk about complex social phenomena, like major changes in crime trends, I think people need a decent amount of humility, and far too often I do not see that humility,” he said.

Cris Moore, a professor at the Santa Fe Institute and one of the lead authors of the study on bail reform in New Mexico, pointed out that jailing more people doesn’t come without costs.

“You would be putting a lot of people behind bars,” he said. “You would be expanding the jail population. You’d be costing taxpayers more.”

Moore noted that while crimes committed by those awaiting trial are often blasted on the media, the collateral consequences of holding people behind bars often don’t make headlines.

“They can’t take care of their kids,” he said. “They can’t pick up their kids from school. They can’t keep their job. They can’t pay their rent. They lose their housing. They lose custody. Their marriages fall apart.

“It’s harder to mount a good defense when you’re in jail, because it’s harder for your defender to meet with you. You might be quicker to accept a plea deal, even if you didn’t really do the thing you’re accused of.”

These losses aren’t just personal problems but can lead to communitywide issues. The act of incarceration itself has been found to lead to increases in crime. One study found that for every 10,000 people detained, an additional 400 felonies would be committed and 600 more misdemeanors than if they had been released to await trial. Lost wages from lost jobs, a criminal record that makes it harder to find new work, and disruptions to housing and family life are all risk factors for criminal activity.

These facts and figures — at least in New Mexico — don’t seem to be making much of a difference. While bail reform passed with 87% of the vote in the state in 2016, a recent poll by the Albuquerque Journal found that a nearly identical percentage now want to rescind the measure.

Moore isn’t surprised.

“You don’t bring data to a story fight,” he said.

Ad assumption: But the crime rates are soaring!

The FBI released its latest data earlier this week. Cold hard facts are supposed to inform levelheaded conversations and policy decisions about crime, right? But experts warn this year’s release — whether intentionally or not — could distort the public’s understanding of crime in America.

That’s because the FBI has changed the ways in which it collects crime data from police departments. Here’s a simple example: If a perpetrator had shot someone in the process of a carjacking, the FBI’s old system would only count the most serious crime: the shooting. Yet the new method collects richer data. It would include the shooting and the carjacking. Hence, more crimes will be counted, but that doesn’t necessarily mean more crimes are being committed.

Complicating matters, not all police departments have transitioned their own record-keeping to match the new FBI format. San Francisco, for example, doesn’t expect to switch to the new tabulation system until 2025. The Brennan Center reports that law enforcement agencies patrolling roughly half the US population have not reported a full year’s data. That includes major metros, like New York City.

When the FBI doesn’t have the full year’s data, it estimates the number and assigns “confidence intervals” to them. These confidence numbers are a little like the pluses or minuses typically found in, say, a political poll.

“There’s a real risk,” Grawert said of the FBI data, “that people overread it and overread it for politically motivated conclusions.”

Not only that, but just because the data is newly released doesn’t mean it’s current, Grawert said. What the FBI puts out in the coming days will reflect the picture from 2021 — not what is playing out in real time.

Media outlets unaware of the changes to the calculations may misinterpret the new data, or politicians may purposely exploit the changes to advance their narratives.

In either case, researchers will keep shaking their heads over another category not collected by the FBI: crimes against math. ●

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated the type of felony in the Santa Fe Institute and University of New Mexico's finding on crime prevention.