One Valentine’s Day, I knelt on the bedroom floor of the tiny Brooklyn apartment I shared with my boyfriend, clutching a deboning knife. There was blood under my fingernails. The black trash bag that I’d cut open and laid across the wood floor crinkled under my knees as I stared at twelve pounds of disassembled raw meat in a pool of its own blood. A roll of string, its loose end damp and frayed, lay next to me amid this macabre picnic. On the nearby writing desk my laptop glowed with online instructions for how to debone and tie a pork shoulder.

I had never eaten meat in my life. My mother had raised me vegetarian and I’d never had the urge to break that fast. I didn’t find meat particularly gross or offensive; I simply did not identify it as food. I would just as soon have tried to eat pillow stuffing or tree bark. I did not even know that “pork shoulder” existed until the February day that I won it at the local supermarket. The cashier had announced that I was the first customer that day to spend over $100 and could pick out any piece of meat my heart desired. Probably, they had some holiday stock nearing expiration. My first instinct was to decline the prize, but then inspiration struck. I would recoup my winning and cook it for my meatloving boyfriend. I picked out the largest hunk of dead animal I could find.

“What on earth is that?” my boyfriend asked when I returned home with the boulder of meat.

“Pork shoulder!”

“Yes. But why is it in our apartment?”

“I’m going to cook you a roast for Valentine’s Day,” I said.

“That’s ridiculous.” I shrugged, but did not elaborate. What could I have said? I am trying to save our relationship by forging one with twelve pounds of dead pig? It would have been the truth.

Alex and I had met for our first date three years earlier, at a restaurant in the West Village renowned for its vegan fried “chicken.” I had chosen the venue and he, despite being an avid carnivore, had gamely agreed. I was twenty-five years old, in graduate school for creative writing, and had just quit my job as a professional dominatrix, where my shifts consisted of dressing up in corsets, fishnets, stilettos, and the occasional nurse costume to enact the fetishized scenarios of my clients, who were mostly stockbrokers. While it didn’t include nudity or technical sex, it was a sex-industry job. Our erotic trade just happened to be golden showers, verbal humiliation, and corporal punishment rather than lap dances or intercourse.

As we traded bites of our faux-cutlets, I marveled at how normal Alex was. Then I gave him the summary: I had been raised by a Buddhist psychotherapist and a sea captain, dropped out of high school at fifteen to be a writer. I was two years clean and newly returned to the straight working world. Oh, and most of my past lovers had been women. “Wow,” he said. “I never would have thought to drop out of high school to pursue my actual dreams.” He had been raised by a banker and a housewife in Westchester and attended the best film program in the country. That is, he had followed his dreams in the manner prescribed by our culture. Though his admiration flattered me, I didn’t see my own wayward path as exotic or impressive. I had always pursued my desires with intense focus, but there is a fine line between confidence and recklessness and I had crossed it a hundred different ways.

I did not have words yet for the ways that four years of banking on my body had convinced me that it was my only currency. I had just reentered the normal world, and I was prepared to get kicked back out.

Three months after that dinner, we moved into a small one-bedroom in Prospect Heights. The neighborhood, like me, was newly gentrified: in that moment when baby carriages and occasional chalk outlines share the same sidewalks. I could never have afforded the tiny apartment on my adjunct professor salary, but together we could.

I did not have words yet for the ways that four years of banking on my body had convinced me that it was my only currency. I had just reentered the normal world, and I was prepared to get kicked back out.

The day I first met Alex’s parents was warm, midsummer. I stared at my closet that morning, considering the impression I wanted to make. I still had a suitcase of dominatrix outfits under our bed and my arms were covered in tattoos, but I was intent on projecting the woman I was becoming, not the one I was trying to leave behind. I selected a beige silk blouse that buttoned at the wrist and twisted my hair into a chignon.

I have always interviewed well, and that afternoon was no exception. “You don’t have to hide your tattoos,” Alex said on the train home. “I know,” I said. “I just want them to get to know me first. I won’t hide them forever.” But a year passed, and then another, and it never seemed like a good time to expand their impression of me. Instead, I accumulated a wardrobe of wrist-length blouses suitable for all kinds of weather.

I also became a cardigan collector. When I started teaching undergraduates, I knew that my personality endeared me to my students; I had passion for my subjects and made them laugh. I knew that I was a good teacher, but still felt marred by my past, afraid that if visible it might invalidate my qualifications. Tattoos don’t necessarily boast of a past checkered by spanking men for money or shooting speedballs, but in my mind they did.

Imposter Syndrome: Defined by the American Psychological Association as “an internal experience of intellectual phoniness that appears to be particularly prevalent and intense among a select sample of high achieving women.” Unsurprisingly, “societal sex-role stereotyping appear[s] to contribute significantly.” Add a history of marketing one’s sexuality as primary source of income, and you might understand the fear of blowing my own cover.

The only place where I didn’t feel like a double agent was in writing. Instead of tugging down my sleeves, I uncovered things. The page was the only place where I felt free to examine the soft ground between my past and present. I had spent years in different costumes, changing to fit the disparate social landscapes that I inhabited. At my desk, I had no audience but myself.

The first time I wrote about my time as a dominatrix, it poured out of me the way words had in my childhood notebooks. I had never been fully honest with anyone about that experience. I hadn’t known how badly I wanted to. When I shared those first pages with a mentor, he said, “You have to write a book. Drop whatever else you are working on.”

I didn’t want to think about exposing myself so wholly, uncurated by my deep desire to please everyone, to finally pass. I had never been so honest as I was in those pages. When I did think of it, the prospect equally terrified and exhilarated me.

That day a clock started ticking. I knew that such a book would destroy the control I had over how people saw me. There would be no sleeves long enough to draw over those truths. “It’s going to be great,” my boyfriend said, not having read a word of it. I nodded. And when I sat at my desk at the foot of our bed and excavated those memories, asked the questions of myself for which I did not yet have answers, it was great. But when I stopped writing, I could hear the tick of that clock.

Ten years later, I know that three months is not long enough to know someone. That twenty-five is not old enough to know yourself. But I knew that I loved Alex. He was the first man whom I really trusted. My body had developed early and dramatically as an adolescent and that introduction to the world of male desire—men hollering at me from truck windows when I was twelve, crude gestures in the middle-school hallways—had been a fast and hard lesson in the ways my female body both empowered and disempowered me.

Alex and I made love every night for two of our three years together. In the safety of that love, I discovered my own desire. Not the thrill of making a man who had paid for it crawl across the floor begging. Not the compulsive need to be desired, but desire itself: my own fast breath and hungry hands. I wanted Alex on me, inside me, his hands remaking and holding me in at the same time. I was a feminist. I had been happy to be gay. But though it shamed me, I could not deny the appeal of such simplicity. To be like everyone else.

When I finished the book, he was the first person I showed it to.

“It’s great, Melissa,” he said. “Though hard to read about those men.”

“But I never slept with any of them,” I said.

“It’s not that. I’ve just been able to think of that version of you as a different person. My you seemed so separate from those stories.” I wanted to say, It was a different person! But I couldn’t.

For a long time, I had also separated my present self from that past girl. And writing the book had built a bridge between them. To write an honest book, I had had to go back, to look at what that girl had needed, and why she found it in such dark places. I couldn’t exile her again.

“I’m really proud of you,” he said. Though on the day that the book sold, instead of celebrating, he sank into an inexplicable funk. My excitement fizzled as we ate leftovers in silence. I fell asleep in front of the television, alone.

The next time we sat on his parents’ patio eating crudités, I told them that I’d sold a book. “A memoir,” I said. “About my wild college days.” “Oh my,” chuckled his mother, an elegant woman with a sleek gray bob. “Well, we will look forward to that.”

Over the next few months, Alex and I formulated a plan. There was no hiding the book’s subject, but we would give his parents an abridged manuscript—enough material to give them a sense of the storyline while sparing them the details. As we conspired, a part of me wished that I could do the same for my own mother. But she was a therapist who had built her life around hearing the whole truths of other humans. There was no way she would accept a partial truth from me, and ultimately, I was glad for that.

Ten years later, I know that three months is not long enough to know someone. That twenty-five is not old enough to know yourself. But I knew that I loved Alex.

As the publication day neared, I decided to start training for the New York City Marathon. Alex worked longer hours as a video editor. In retrospect, I think we were both afraid that if we stopped moving we would have to face what was happening to us.

This is how a lifelong vegetarian ends up crouched on a garbage bag covered in raw meat on the floor of her own bedroom. I understand why he found it ridiculous—why would I insist on cooking him a meal that I would never myself eat, could not even taste if I succeeded? I couldn’t explain why back then, though now it seems obvious: by doing so, I would prove that I could be myself—this weird, queer, kinky combination of things that had no place in the Cheever-esque realm of his upbringing, and still give him what he needed. If I could master those fifteen pounds of meat so outside the realm of my own tastes, maybe I could stay inside a life that didn’t quite fit. Of course, it was a doomed effort, but these are the sort of Hail Marys we throw when faced with the hardest dilemmas. It was me or us, and I didn’t want to choose.

The roast came out wonderfully. It was tender and savory and filled our tiny apartment with a delicious and slightly repulsive scent. He barely touched it.

In order to stay in my relationship, I detached from it. I ran and typed and cooked and curled myself against him in sleep. But my heart was already gone. I didn’t know that, though, and so when I fell hard in love with a woman who lived down the street, it came as a shock.

Before my book was published, before she and I touched each other, I took him to the house where I was raised, on Cape Cod. Maybe I thought there was a chance that he would see how the past could not be separated from the present. But he didn’t. As we sat on a picnic table, ice cream cones dripping down our wrists, I said, “I can’t do this.”

In the best cases, love leads us to a truer version of ourselves. It seems mercenary to say that the people we love are our teachers, but it is true. They are also whole people, with their own hearts and lessons and breakings. But all I speak for is myself. The way I have gone to the furthest extremes to find my own center.

After I left him, I stopped wearing long sleeves. I stopped offering abridged versions of myself. He had never asked me to do that. But he taught me how to stop.

Slow-Roasted Pork Shoulder

1 pork shoulder (bone-in, skin-on)

Preheat oven to 250°F. salt and pepper

Generously season pork shoulder with salt and pepper, then set the pork on wire rack that fits inside a rimmed baking sheet.

Place it in your oven and roast for about 8 hours. (Test readiness by slicing with a knife, or inserting a thermometer—the temperature should read 175°F.)

To get extra-crispy skin once the meat is tender and fully cooked, turn up the oven temperature to 500°F and roast for an additional 15 minutes until the skin crackles.

Remove from oven and allow to rest and cool an additional 15 minutes. Serve. ●

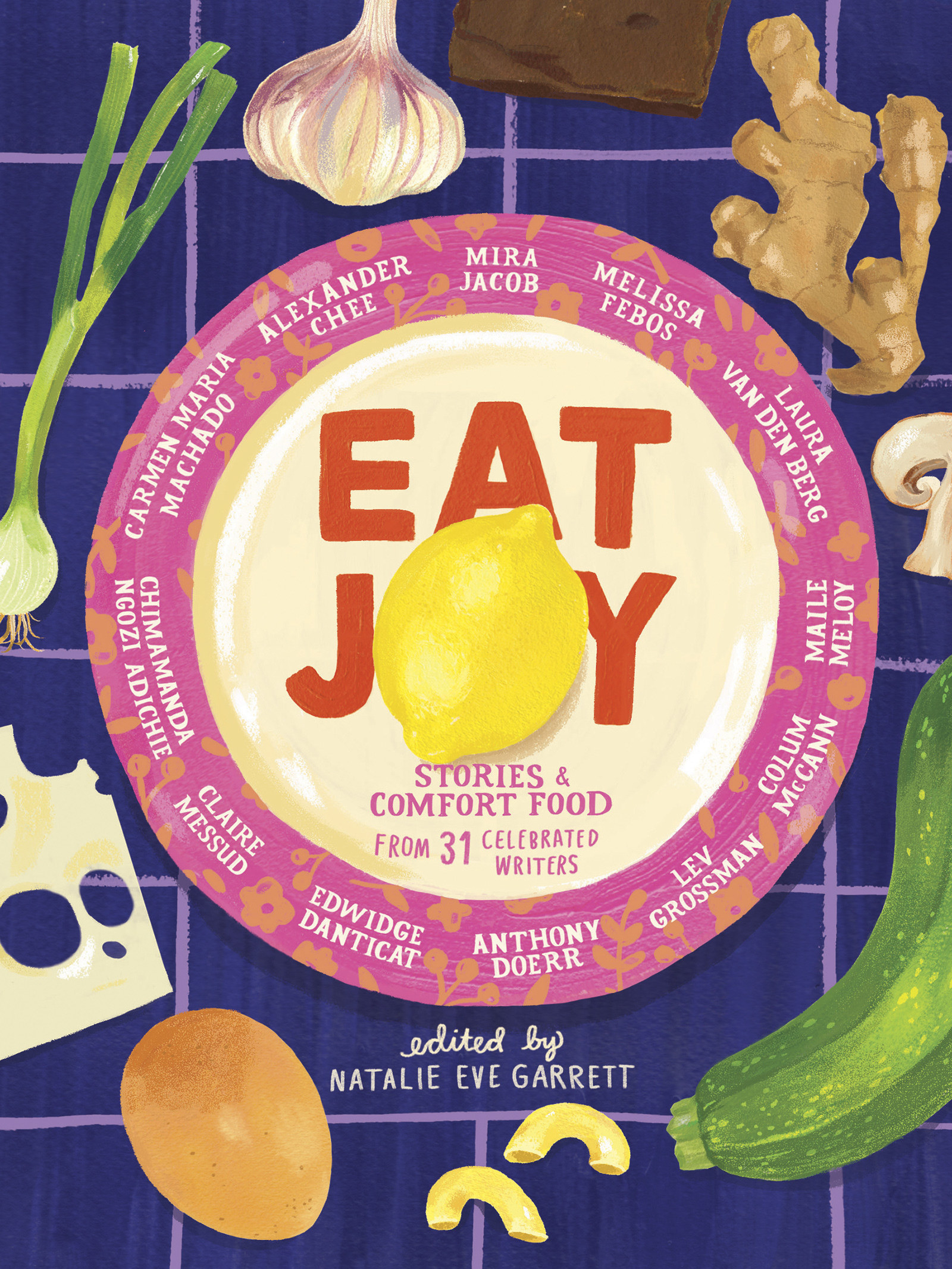

"Long Sleeves" by Melissa Febos, from Eat Joy: Stories & Comfort Food From 31 Celebrated Writers, an anthology edited by Natalie Eve Garrett. Used with permission of Black Balloon Publishing. Copyright © 2019 by Natalie Eve Garrett.

Melissa Febos is the author of the memoir Whip Smart and the essay collection Abandon Me. She is the winner of the Jeanne Córdova Nonfiction Award from Lambda Literary, the Sarah Verdone Writing Award from the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, and the recipient of fellowships from the MacDowell Colony, Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, the BAU Institute, the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund, Vermont Studio Center, and others. Her work has recently appeared in Tin House, Granta, the Believer, the Sewanee Review, and the New York Times. Her third book, Girlhood, is forthcoming from Bloomsbury in 2021.