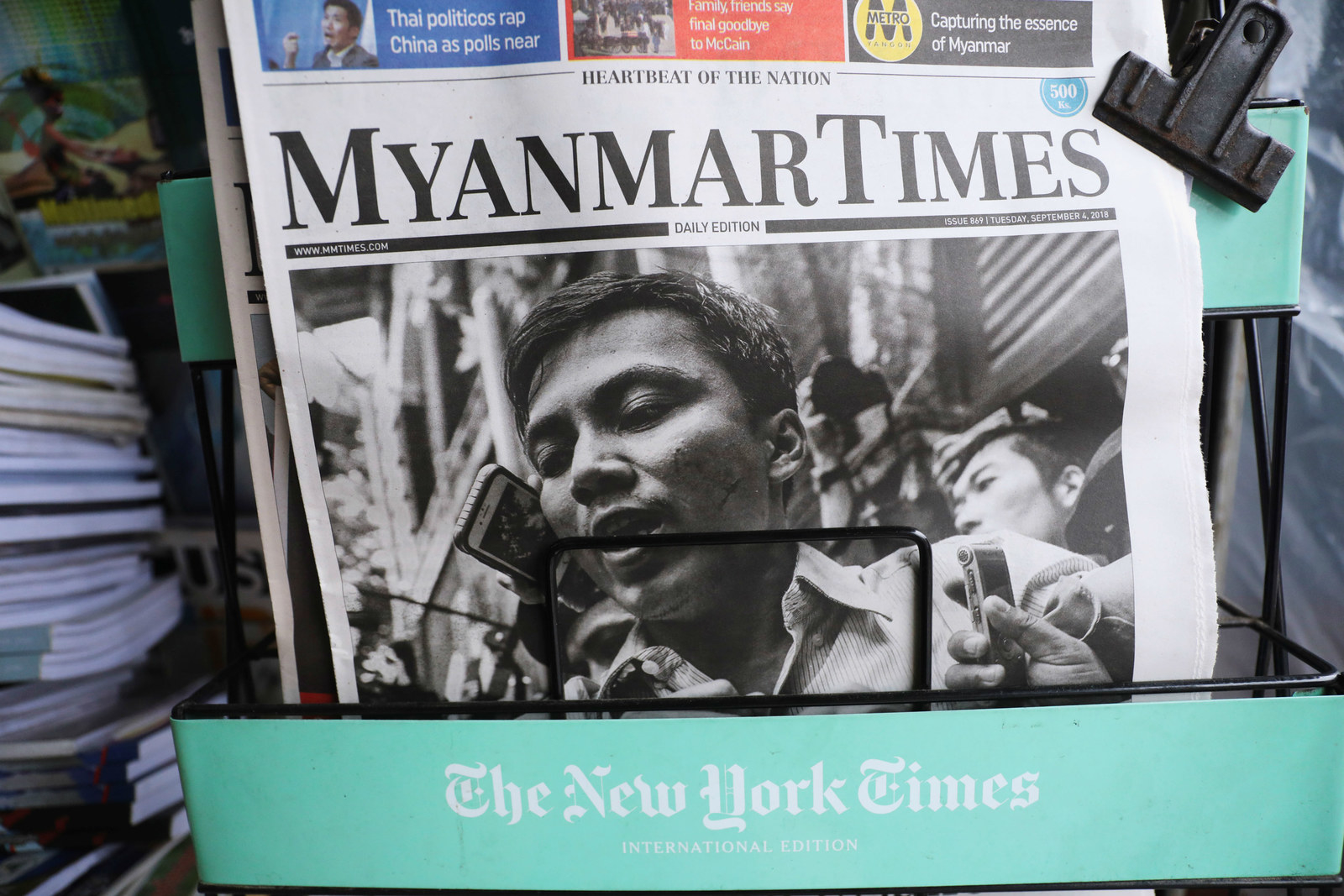

A Myanmar court sentenced two Reuters reporters to seven years in prison this week after they uncovered a massacre of Rohingya Muslims, and people are pushing for the government of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi to grant them amnesty.

The case of the two reporters, Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, has sparked an international outcry from human rights groups, press freedom advocates, and the EU and the US State Department, among others. The journalists were detained in the midst of investigating a massacre of Rohingya Muslim boys and men in what a police captain testified in court was a sting operation. They were charged and convicted under a colonial-era law on state secrets.

The reporters are being held in Yangon’s notorious Insein Prison, which over the years has housed hundreds of dissidents including members of Suu Kyi’s own political party.

Their case comes amid heavy international criticism of both Suu Kyi and Myanmar’s powerful military over what the UN has termed the ethnic cleansing of Rohingya Muslims. More than 700,000 Rohingya people fled the country last year amid a state-led campaign of violence. The International Criminal Court said on Thursday that it has jurisdiction to rule on the deportation of Rohingya people from Myanmar to Bangladesh as a crime against humanity.

Under Myanmar’s law, Suu Kyi, whose official title is state counsellor, does not have the ability to grant a pardon on her own — that power lies with the country’s president. But as the country's de facto civilian leader, she’s regarded as the person with the power to make the decision.

“The Constitution and the Code of Criminal Procedure give the President unrestricted powers to issue a pardon or commute a sentence, so in our view, there are no legal impediments to securing Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo’s immediate release,” said Frederick Rawski, director of the Asia Pacific program at the International Commission of Jurists. “Aung San Suu Kyi, as State Counsellor, does not formally wield that power, though as a practical matter, everyone understands that she is the decision-maker.”

Pardons for prisoners in Myanmar were a regular practice even during military rule, typically taking place at holidays including the Burmese New Year festival — which usually occurs in mid-April — or other important occasions.

“Granting amnesty to the Reuters reporters would have relatively little political cost for Suu Kyi,” said Hervé Lemahieu, director of the Asian power and diplomacy program at the Lowy Institute. “There’s no reason why it couldn’t be done in this case, and done at any time.”

The 7 years jail conviction for two #Reuters journalists in Myanmar who investigated the murder of Rohingya people is the darkest signal for the future of the country. The Nobel Peace laureate Aung San Suu Kyi backs up the massacres and now backs up the oppression of the press. https://t.co/3vZiUU6dLP

The conviction of the two reporters came on the heels of a UN fact-finding mission’s report that called for top leaders in the military to be investigated and prosecuted for genocide, and criticized Suu Kyi for failing to use her “moral authority” and official position to stem last year’s violence against the Rohingya. Suu Kyi’s defenders say she has little sway over the military and could have done little to halt the crisis.

Press freedom advocates have noted the case has created a chilling effect for journalists in the country at a time when the media is already under pressure. Last year three journalists were jailed for two months after they flew a drone near the parliament building in the capital city of Naypyidaw. And rights groups say the country’s defamation law is routinely used to punish critics of the powerful.

Whether or not the reporters are freed, the damage may already be done. The message to journalists is clear — investigate sensitive subjects and you could face prosecution.

“The deterrence effect of detaining, trying, and convincing journalists who are seen to stray so far into sensitive areas for the state has already been convincingly laid down,” Lemahieu said.