ROCKY RIDGE, Utah — About 60 miles south of Salt Lake City, at the end of a long, winding, dirt road off the highway, a small cluster of houses sits at the foot of a desert mountain. The neighborhood landscape is littered with children's things — plastic playground equipment, abandoned toys — and the backyards are covered in clotheslines, with denim shorts and Sunday dresses of all sizes hanging off them like ornaments.

But the houses themselves command the most attention. They look as if someone took a bunch of starter homes and glued them together with communal kitchens and shared garages. The structures’ aesthetics vary, from utilitarian ranches with unpainted decks to well-kept A-frames with manicured lawns. And virtually every structure is in a state of renovation, expanding and shape-shifting to make room for more beds, more groceries, more children — and more wives.

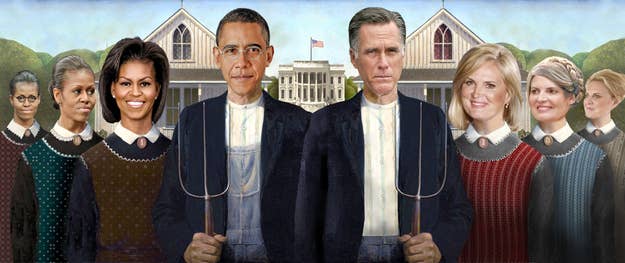

This is Rocky Ridge, Utah, one of the fastest-growing polygamist communes in the country, and an unlikely symbol of a genealogical subplot that links America's two main presidential candidates. While neither Mitt Romney nor Barack Obama is keen to talk about it publicly, the family trees of both are rooted in polygamy, a practice that, for each candidate, has defined generations of family history.

It's a connection that's been largely ignored by the campaign chroniclers this year, without any objection from the candidates, both of whom have had to grapple with far less exotic biographical eccentricities. But while reporters may relegate the men’s polygamist roots to a footnote in the broad story of the election, the candidates' common background is being celebrated across the diverse spectrum of American polygamy.

From reality TV stars to reclusive religious zealots, polygamists throughout the country are watching this presidential election with a mix of pride and frustration — acutely aware that that Romney and Obama come from "polygamist stock," and yet resigned to the fact that neither candidate is likely to defend their lifestyle. Meanwhile, a growing number of polygamists are going public with their stories, pop culture continues to obsess over the taboos of plural marriage, and the family from TLC's Sister Wives is waging a high-profile legal battle to decriminalize polygamy in Utah.

More than ever before in U.S. history, polygamists view this year as an opportunity to convince the American public that they have something to offer the world — and they're pointing to the presidential election as Exhibit A.

Call it the polygamist moment.

Anne Wilde still clearly remembers the moment she watched Mitt Romney throw his heritage under the bus.

A practicing polygamist and leading advocate for "plural marriage" rights, Wilde had watched Romney's political rise over the years with an unusual sense of personal investment. She knew his agenda wouldn’t include the polygamist equality that she’d spent years fighting for as co-founder of the advocacy group Principle Voices. She knew he was just a politician trying to win an election. And she suspected that, like most mainstream Mormons these days, he probably had complicated feelings about plural marriage, a practice the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints abandoned more than a century ago.

But she also knew this was a man who came from a long family line of proud polygamists — ancestors who embodied the best qualities of the lifestyle she loved. And, in 2007, as Romney ascended to the top tier of the Republican presidential primary, Wilde found herself eagerly cheering him on.

Then, in May, Romney gave an interview to Mike Wallace of 60 Minutes, where the subject of polygamy came up.

"There is part of the history of the church's past that as I understand is troubling to people," the candidate said. "Look, the polygamy, which was outlawed in our church in the 1800s, that's troubling to me. I have a great-great grandfather. They were trying to build a generation out there in the desert. And so he took additional wives as he was told to do. And I must admit, I can't imagine anything more awful than polygamy."

Wilde was crushed. A Brigham Young University graduate who grew up in the Mormon Church, she had left the faith of her childhood and turned to polygamy after her monogamous marriage fell apart. She says she spent the next 33 years as a happy second wife to her husband until he passed away in 2003. Now, she had just heard a presidential candidate dismiss the life she had chosen as “awful.”

"When he said that, my heart just skipped a beat," Wilde, now 76, recalled. "I thought, oh no, why did he have to be so strong against it?"

Since that moment, her enthusiasm for Romney has been dampened, and she's learned not to expect too much of him — a disappointment she said many in the polygamist community share.

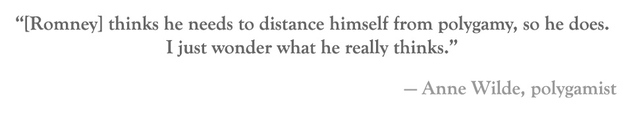

Obama, meanwhile, has kept mum on the subject of his ancestral polygamy since entering the White House, Wilde said, though she suspects he wouldn't be quite so harsh, since he doesn't feel the same compulsion to overcompensate that his Mormon challenger does.

“Romney’s a politician and he’s going to say what he has to say to get elected,” said Wilde, who — because she is widowed — can speak about polygamy without facing prosecution, unlike most practicing polygamists. “He thinks he needs to distance himself from polygamy, so he does. I just wonder what he really thinks.”

Still, it's strange that Romney has had to work so much harder than Obama to publicly disown polygamy. After all, the president's family stopped practicing it much later than Romney's did.

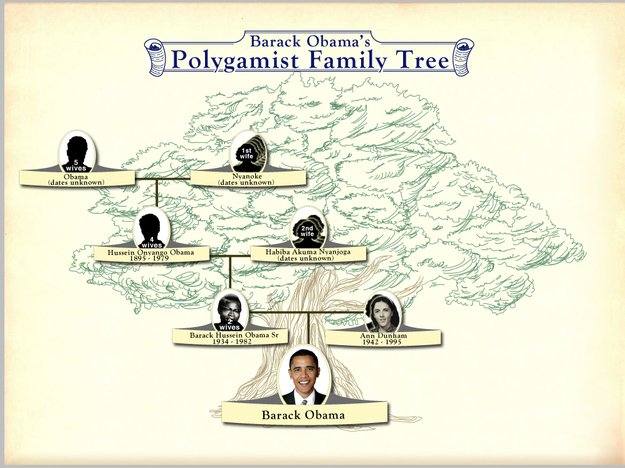

As biographer David Maraniss reports in his book, Barack Obama: The Story, the president's great-grandfather was a polygamist in western Kenya — where it was a common practice in the Luo tribe — and took five wives, including two who were sisters. Obama's grandfather had four wives; and his father already had a wife in Kenya when he went to the University of Hawaii, fell in love with Ann Dunham, and married her. (Obama's mother was not aware that her new husband was already married in another country.) It could be argued, then, that the President is the first Obama not to practice polygamy on his father's side of the family since the 19th century.

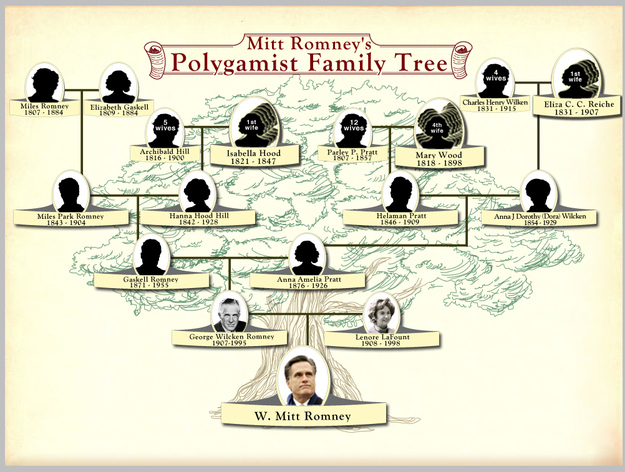

In Romney's case, the practice was put to an end several generations ago, but the list of known polygamist relatives is much more expansive, thanks in part to his church’s commitment to genealogy research. Both of Romney’s paternal great-grandfathers, early leaders in the Mormon Church, practiced polygamy, and both spent much of their lives in Mexico, after fleeing a U.S. government crackdown on Mormon plural marriage. One of them had five wives; the other had four — and that's where it stopped. Romney's grandfather and father were born in a Mormon colony in Mexico, but both were monogamists.

Of course, the Mormon polygamist vote isn't exactly a politically prized demographic: Most experts peg the total U.S. population at around 15,000, largely tucked away in obscure corners of red states like Utah, Arizona, and Texas. But as polygamists grapple with a presidential race that pits two descendants of plural marriage against each other, the dynamic offers a unique case study in the politics of identity.

"We tend to lean, locally, toward candidates who are most sympathetic to our cause," Wilde said. "But nationally it's different. I think politically, most of the fundamentalists are either Republican or independent, and most of us will either vote for Romney or Ron Paul.... But it's interesting to note that, in order for us to get this lifestyle decriminalized, we have to look to the liberals to make a change."

Given how Obama and his party have championed marriage equality this year, Wilde said the president could theoretically have an opening in the polygamist community — but it would take a push. And Obama’s silence on his own family history of plural marriage hasn’t done much to win them over.

"I've never heard any public comments on polygamy or his ancestors," Wilde said.

Besides, while the fundamentals of the marriage arrangement may have been the same, Kenya's a long way from Rocky Ridge.

"It's very different," Wilde said. She paused, then repeated herself: "It's just very different."

Today, the modern remnants of those polygamist subcultures, Mormon and African, are fighting for survival on the fringes of American society.

Polygamy is illegal everywhere in the United States, but in Utah it feels extra-illegal. Since 1890 — when the Mormon Church officially abandoned plural marriage to get the federal government off its back and clear the path for its western Zion to gain statehood — Utah has aggressively evolved into one of the most anti-polygamy states in the country. Eager to modernize their image and put distance between the bearded polygamist brand their state was historically saddled with, the legislature long ago crafted a series of tough laws designed to close the loopholes used by proponents of "the Principle," as fundamentalist Mormons call polygamy.

For example, not only is it against the law in Utah to marry more than one person; it's a crime for a married man to cohabit with another woman — a provision meant to prevent patriarchs from marrying one wife civilly and then keeping the rest of his "spiritual wives" under the same roof.

For a long time, what that meant was that if you were living a lifestyle even remotely resembling historical polygamy, there was a chance the police would raid your home, take your children into their custody, and throw you in jail.

There were, of course, plenty of sound reasons to justify this hardline stance. In its most extreme iterations, fundamentalist Mormon polygamy has been a social cancer that puts children at risk and harshly oppresses women. As recently as last year, cult leader Warren Jeffs was convicted of sexually assaulting two girls, ages 12 and 15, whom he'd spiritually "married." And a 2011 Rolling Stone exposé described one particularly brutal polygamist clan in Salt Lake City that operates as an organized crime family, running under-the-table businesses, stashing cash and gold in nondescript safe houses to avoid taxes, and sending violent "enforcers" to threaten outside enemies and family snitches alike.

But defenders of plural marriage say these stories are the exception, not the rule.

"We are basically law-abiding citizens, we take care of our families, we don't believe in forced marriages or suppressing women," said Wilde. "Staying with underage girls is horrendous."

And while Utah's strict anti-polygamy laws may have helped prove a point, experts say they also served to drive polygamist religious sects further underground, where malnutrition, incest, and child abuse regularly went unreported to the police.

The state began to change its tack in 2003, when Attorney General Mark Shurtleff implemented the "safety net" policy, urging polygamist whistle-blowers to come forward with crimes taking place in their communities, and promising not to prosecute otherwise law-abiding plural families. The new goal, said one state official, is for Utah polygamists to eventually function like the safest and most successful Amish communities in Pennsylvania: protected by organized society, but living mostly independent of it.

Meanwhile, on the other end of the American polygamy spectrum, academics estimate that as many as 100,000 Muslims, largely West African immigrants, are secretly practicing polygamy in the U.S. Unlike fundamentalist Mormons, these Muslim communities tend to congregate around northeastern urban centers, like New York and New Jersey.

In a 2008 series on polygamy among U.S. Muslims, NPR revealed multiple cases where women were trapped in an unwanted plural marriage — unable to flee for fear of deportation, or unable to survive without their abusive husbands' income. But the series also reported on a deliberate shift toward polygamy in South Philadelphia's black Muslim community, where advocates say the lifestyle could effectively address common inner-city social ailments caused by children growing up without fathers.

These two American polygamist subcultures rarely, if ever, intersect, and each appears to view the other through a lens of exoticism. In the premiere issue of polygamist magazine Mormon Focus, in 2003, a feature lamenting the decline of polygamy in East Africa was accompanied by a sidebar that began, "Generally speaking, for many native Africans morality is not part of their culture, and they see no need for any kind of marriage commitment."

What the two communities do share is a commitment to secrecy, and a tendency to survive in the shadows. But now, a small handful of Big Love-style polygamists is trying to buck that trend as well — emerging from obscurity with a mission to put a modern face on their lifestyle. The most famous of these well-dressed, laptop-wielding crusaders is the Brown family, who star in a hit TLC reality show called Sister Wives. After three seasons of showcasing their sunny, fashionable lives on cable television, Kody Brown and his four wives now find themselves embroiled in a battle to overturn Utah's laws against polygamy.

Their lawsuit — and their relentlessly upbeat TV show — have made them heroes in the polygamist community, and supporters believe their popularity represents the beginning of the mainstreaming of plural marraige.

"I think Kody Brown has done more singlehandedly than any other person to make people aware and generate positive comments about [polygamy]," said Marianne Watson, a practicing polygamist and historian in Salt Lake City. "Utah will never change its laws until there is more pressure from without than from within. I think Kody’s family is doing us a great service in that regard."

But for all the Browns' star power, the members of their church remain decidedly suspicious of outsiders. On a recent summer afternoon at Rocky Ridge — which includes, at the center of town, a chapel for the Apostolic United Brethren (the same church the Browns belong to) — women peered through their windows as an unfamiliar rental car wound its way though the largely desolate town. A couple of them offered reluctant waves to the visitors; most of them did not.

Here, it appeared, discretion was still the rule.

"Oh boy, they're hauling in the food. Now you get to observe what many cameramen have gone gaga over!"

Joe Darger was sitting next to one of his wives in the chicly decorated living room of his suburban Salt Lake home, looking through the window as a few of his 24 children marched in and out of the house like ants, carrying several bags of groceries at a time.

"It's shopping day at the Darger home," he declared.

It was, indeed, a spectacle; and Darger — a well-muscled man with a shaved head, wearing jeans and flip-flops — has had plenty of opportunities to present it to curious observers lately. Last year, he and his three wives published a memoir, Love Times Three, advertising an inside look at their marriage. Their decision to go public landed them in a very small club of American polygamists who have determined that getting loud, rather than quietly hiding, may be their best shot at defending their lifestyles. And they've been rewarded with nonstop media appearances.

Like the Browns, the Dargers' brand is aggressively modern. The teenagers tinker with smartphones and play in indie rock bands; the wives wear jewelry and jeans that look like they come from department stores.

But unlike the oversexed image depicted in HBO's Big Love, the Darger family also strives for a sort of Christian wholesomeness that would seem to identify them with cultural conservatives. They hang placards with religious maxims on the walls, they abstain from alcohol, and they read scripture together as a family. They believe homosexuality is sinful, and they abhor abortion — earnestly bemoaning the absence of God in public life, and yearning for a return to "family values." In short, they live lives that even the most ardent Rick Santorum acolyte would approve of (with one obvious exception).

"We're about faith, family, and getting the government out of our lives," Darger said. "It's a quintessential conservative argument."

Which is why it was so jarring when, about 20 minutes into the discussion he started dropping terms that were borrowed from another community that hasn't always gotten along with religious right: The gay rights movement.

"We made the decision as a family to come out," he said, at one point.

"All we want is our equal rights," he said, at another.

When finally asked whether he saw parallels between the gay marriage cause and his own, Darger didn't hesitate: "Definitely."

Gay rights advocates want nothing to do with the polygamists, having spent years batting down the right's argument that the freedom to marry could extend in unexpected directions. But to get polygamy decriminalized, Darger said he is modeling his strategy after the successes of that movement (which he supports on Constitutional principle). As part of the effort, he and his family are waging a public awareness campaign to demystify their lifestyle.

"You've got Mormons coming to the forefront culturally, and you've got gay marriage and openness about gay lifestyle coming to the forefront culturally," he said. "Those two things have certainly prepared people for this type of exposure... They just need to see polygamist families that hold on to their ancestors' principles, but not necessarily their clothes."

Darger has also been working to organize polygamist voters in Utah, and they've been courting legislative candidates who will back their issues.

"We're trying to show that there's a constituency here," he said.

But for all his political involvement, Darger can't quite get behind either of the major-party candidates — even as he uses their polygamist ancestry to make his case. He regularly updates the family’s widely-read Facebook page with reminders that both Romney and Obama have polygamy in their family histories.

"I love it," Darger said of Obama's polygamist roots. "To me it's part of that discussion. Polygamy is the most ancient of marriage practices. We have a society grappling with rapid change, and yet trying to hold on to the past. I think polygamy really speaks well to that. It's like this relic of the past that fits into the progressive future."

And while he said he's glad to see Mormonism becoming "part of the social fabric," he has mixed feelings about Romney's rise: "It's not some black and white answer for us."

"We have an uneasy alignment with the traditional LDS Church," he said. "Traditionally, they have been the ones most easily wielding the bully stick. And so it's not like, 'Oh great a Mormon's coming to power.’ Because Mormons in power have not necessarily been kind to us."

Come November, he said he will probably stay true to his libertarian beliefs and pull the lever for Gary Johnson. Earlier this year, Darger and his wives were invited to address the Libertarian Party convention, and Johnson reassured them that he doesn't believe government should have any place regulating marriage.

For the polygamist patriarch, that pretty much sealed the deal.

As he put it, “I’d have to hold my nose if I voted for the other two.”