Paul Ryan, perennially polite and always respectful of his elders, was on his best behavior this week when he stood to take questions at a packed press conference in Washington. The wonkish, 46-year-old Speaker of the House had just concluded a widely hyped private meeting with Donald Trump, and for the next 10 minutes he would have nothing but kind words for the billionaire demagogue who has thrown his party into chaos.

"I heard a lot of good things from our presumptive nominee," Ryan said.

"I actually had a very pleasant exchange with him," Ryan said.

"He is a very warm and genuine person," Ryan said.

"Good personality," Ryan said.

This conciliatory performance was a far cry from the defiant stand for principle that many conservatives were hoping to see. A week earlier, Ryan had gone on TV and said he was “not ready” to endorse the Republican nominee — a daring little breach of decorum that drew the ire of the Donald, and briefly roused hope in the beleaguered #NeverTrump movement that perhaps they had a new champion. But Ryan’s renegade turn was not to be.

Instead, he has retreated to the kabuki theater of party unity — talking up “common ground” and “core principles”; sitting through meaningless meetings, and smiling through substanceless press conferences; feeding egos, following orders, and biting his tongue to keep the peace. It may not be the most dignified part in the cast, but it’s the one he’s best suited to play.

Over the course of his two decades in Washington, Ryan has cultivated a reputation in GOP circles as a true believer and pioneering policymaker driven by strong conservative beliefs — the "intellectual leader of the Republican Party," as he was routinely referred to in 2012. But those who expected Ryan's ideological conviction to compel an audacious war against his own party's presidential nominee misunderstood him. He has not gotten to where he is by making trouble. He is, at his core, a good soldier.

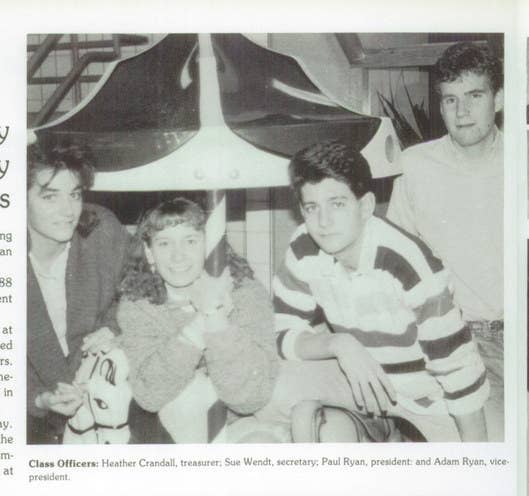

In a bit of trivia that would become a mainstay of the many soft-focus profiles written about him, Ryan was voted “biggest brown-noser” by his classmates in high school. The superlative wasn’t a senior-year anomaly. Interviews with friends, acquaintances, colleagues, and competitors at virtually every stage of Ryan’s life and career suggest the Joseph A. Craig High School class of 1988 had him pegged. He is remembered as a “Boy Scout,” a “team player,” a “respectful young man,” a “suck-up.”

When he was still a teenager, Ryan came to grasp the value of attaching himself to important and connected people — and as a bright, earnest, well-mannered young man, he was a natural at winning over adults who could get him places.

In college, for example, he made a project of befriending Richard Hart, the sole conservative economics professor at Miami University (Ohio). “He would come to the office quite a bit, and very rarely to ask any questions about the course material,” Hart recalled. Instead, Ryan would pepper him with earnest queries about Austrian economics, then politics, and eventually philosophy — hanging on Hart’s every word as though the man were a mountaintop guru in possession of the secrets to the universe. Along the way, the professor wrote a few glowing letters of recommendation for Ryan, and helped set him up with his first congressional internship after graduating.

Upon arriving in Washington, he continued to hone his talent for collecting well-chosen mentors. At 23, while working as a waiter at a Capitol Hill Tex-Mex restaurant, Ryan found himself serving tortilla chips to Jack Kemp, and used the encounter to launch a persistent campaign of ego-stroking and favor-begging that eventually landed him a job at a conservative think tank.

Around the office, he became known for his whistle-while-you-work demeanor, approaching every mundane task dumped on his desk with diligence. Peter Wehner, who hired Ryan at the think tank, recalled assigning him to compile a daily collection of press clippings, and stressing that they needed to be photocopied and collated with perfect precision — “neat and centered.”

“I was very German,” Wehner recalled years later. “But he did it, and he did it without complaining.”

Judith Nolan, Kemp’s daughter who worked alongside Ryan, said it was obvious pretty early on that the young researcher had won over her dad. “At a time when nobody paid very much respect to adults anymore, he was very respectful,” she remembered. “He was also just in awe of Bill [Bennett] and Jack, so they really loved that, I’m sure.” It became commonplace to hear Kemp bellow “PAUL!” from his office, and then see the eager young wonk spring from his swivel chair and scurry toward his beckoning boss.

But while Ryan no doubt recognized that his obsequious style could help him advance, it wasn’t necessarily a put-on. As far as Nolan could recall, he never broke character. She even remembered Ryan taking an uncommonly keen interest in her pregnancy, asking every day, “Oh man, how are you feeling?!” and inquiring frequently about when she had last felt the baby kick. “He was just adorable,” she said. “He was so handsome and so young and so green. His midwesternness stood out. It was like, Oh, of course you’re from Wisconsin… Boys your age don’t talk to pregnant women!”

Of course, Ryan is hardly the first person to butter up a favorite college professor, or fawn over a boss. What has made him unique is the way he has channeled two impulses that seem like they should be in tension — a reflexive, eager-to-please acquiescence (especially to authority figures), and a deeply felt ambition to make a dent in history. Together, these traits have helped power an ascent that landed him on a presidential ticket in 2012, and has since turned him into the highest-ranking elected official in his party.

But the fact that Ryan now seems willing to bury his personal reservations and profound philosophical differences with Trump in the name of peace and partisanship should not be surprising. His career is chock full of such compromises, including as recently as the last presidential campaign.

When Ryan first joined Romney's ticket, many in the political world predicted that his presence would turn the election into a grand ideological battle. Ryan thought so, too. Inside the campaign, he argued vigorously to make the election about more than just a referendum on President Obama. In the spirit of his political idol, Jack Kemp, he wanted to devote time on the campaign trail to selling his conservative economic agenda in diverse, low-income communities. But his arguments fell on deaf ears with the bosses in Boston.

“The strategy set, I focused on the job I had to do as a running mate,” Ryan would later write in his book, The Path Forward. “I needed a good rollout, a good convention speech, and a good debate. Those were my duties.”

He was frustrated, but he had made a conscious choice when he joined the Romney campaign that he would be a team player. No showboating, glory-hogging, grandstanding, game-changing, or rogue-going. He would execute the plays called for him with workmanlike efficiency and diligence.

The greatest test for the low-maintenance, line-toeing came when Romney's now-infamous "47%" video leaked September 2012.

“Paul was fucking livid,” one Ryan aide who was on the plane told me. “He was apoplectic. He couldn’t believe it. Obviously, it was a dumb thing to say and obviously it was bad politically.”

But there was another reason for the good-natured Wisconsinite’s rage. Ryan had been lobbying the campaign to let him give a major address on poverty — and the uproar over Romney's comments now ensured that whatever he said would be seen as cynical.

“It’s going to look totally reactive now,” Ryan seethed to his staff, according to one source. “It’s going to look totally insincere.”

Still, when his damage control instructions came in, he kept his head down and dutifully complied. He read his talking points, and took part in soup kitchen photo-ops, and gave his (watered down) poverty speech — and though much of it did, indeed, reek of a certain canned campaign quality, he believed it was all part of his job. And while that attitude may have served him well, he sometimes misses the days when he was a young, largely inconsequential congressman cranking out controversial, and quixotic, budget proposals.

“I used to be a bomb thrower, " Ryan lamented privately to friends after the 2012 campaign. "I was the Tea Party before there was a Tea Party. Now I’m just part of the establishment."

Adapted from The Wilderness: Deep Inside the Republican Party’s Combative, Contentious, Chaotic Quest to Take Back the White House. Copyright © 2015 by McKay Coppins. Reprinted with permission of Little, Brown and Company. All rights reserved.