BOSTON, Mass. — The day after Super Tuesday, Mitt Romney's senior staff hosted a rare mix-and-mingle with press at a downtown Boston cocktail lounge called Scholars. As reporters strained to squeeze some journalistic value from the off-the-record chitchat, a few members of the campaign’s traveling press corps retreated to a table toward the back of the bar with adviser Eric Fehrnstrom, and campaign manager Matt Rhoades.

The group talked over appetizers for more than an hour before Fehrnstrom and Rhoades decided to call it a night, but it wasn't until after they left that Los Angeles Times reporter Maeve Reston realized she had just been in the company of the elusive man at the helm of Romney's operation.

"Matt and I got up to leave, walked out the door, and Maeve Reston chased us down to say she didn't realize she was chatting with the campaign manager, and wanted to make sure she properly introduced herself,” Fehrnstrom recalled.

This determined obscurity is part of the myth of Matt Rhoades, the behind-the-scenes operative successfully steering the Romney campaign down a narrow path to the nomination. Apparently allergic to press, Rhoades hasn't given a single on-the-record interview this entire cycle, and never goes on television — a fact his colleagues point to as evidence that he is "humble," or "ego-less," or "self-effacing."

As longtime colleague Brian Jones put it, "He's not out there taking self-congratulatory laps in the press... He doesn't care about that stuff."

Indeed, like a hipster for the blue-blazer-and-loafers set, Rhoades's political persona is deeply invested in giving the impression that he doesn't care what you think of him. Whether this apathy is genuine or just marks the recognition that mystery is the best kind of spin, there's one thing Rhoades cares strongly about by all accounts: Winning. And his methodical, tightly controlled, and bullet-pointed approach to politics has been crucial to making Romney — with his complex record and distance from the Tea Party — the presumed nominee of a very conservative Republican Party, no small feat.

Colleagues credit Rhoades in shaping a campaign marked by patience and careful reaction to attacks and by a gleeful, opportunistic unloading of the kitchen sink at rival after rival.

"You've had to engage in hand-to-hand combat as much as you can to get through the next fight," said Jones, who now works alongside Rhoades in Boston. "Matt's good at that."

But if Rhoades gets credit for what is in some ways an unlikely victory in the Republican primary, critics also pin the campaign’s weaknesses on him.

“This is what a campaign run by an oppo guy looks like,” said one rival strategist, arguing that the bullet points haven’t added up to a vision.

Jones allowed that they haven't excelled at "going big" with their message yet. Where Ronald Reagan heralded a "morning in America," and Barack Obama sent shivers down reporters' legs with "change you can believe in," Romney trades in decidedly less inspirational fare. In place of soaring rhetoric, he touts his 59-point economic plan, and antagonizes opponents by dredging up decades-old quotes and obscure House votes.

But if the campaign has lacked vision so far, Jones blames the presence of Super PACs and proportional delegate allotment — not the man in charge of the effort.

"It's challenging to be big when you're constantly having to fend off attack dogs all around you," he said. "The very nature of the campaign has made it harder."

That said, Jones pointed out that Rhoades's skills for political warfare have uniquely prepared him to lead the charge in what has been a bloodbath of a primary.

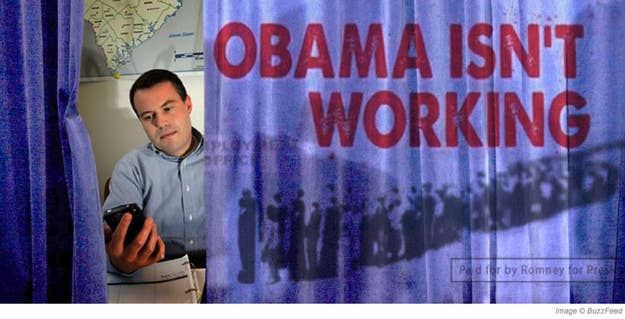

As they've battled their way past a series of ever-emerging anti-Romney figures, the campaign's tactical hallmark has been its swiftly efficient, always-churning press shop, which blasts out several e-mails a day filled with dirt on their opponents. While the independent Super PAC supporting Romney has done much of the actual shooting, it's these emails that provide the ammunition.

With sarcastic headlines and playful graphics, there's an almost gleeful tone to the attacks. For example, in February, after effectively dismantling Newt Gingrich's candidacy in Florida, the campaign quickly pivoted to its next rival with an e-mail headlined, "IF YOU LIKED NEWT GINGRICH, WAIT 'TIL YOU GET TO KNOW RICK SANTORUM." What followed was a list of quotes from 10 different news reports meant to cast both men as corrupt Washington insiders.

Rhoades mastered this brand of politics early in his career as an opposition researcher, eventually rising to direct research efforts for George W. Bush's re-election campaign. There, he mined John Kerry's record for contradictions, and then turned them into a relentless barrage of attacks meant to cast the candidate as a weak, wishy-washy flip-flopper — ironically, the exact same attacks he's now fending off for Romney.

The heat of the campaign was intense, and Rhoades — described by most as quiet and even-keeled — felt the pressure. In a moment famous among political wonks since the Washington Post reported it last year, the young operative once became enraged by something he saw on his computer screen, and punched the monitor so hard that it shattered.

Jones, who was sitting next to him when it happened, now laughs off the outburst — but he said the incident wasn't entirely divorced from his friend's personality.

"Matt has a steely intensity that I think he is very successfully channeling in this campaign. In past campaigns, he's let it get the best of him," Jones said, adding, "He's not a screamer or a yeller, but he is someone who is intense and he's always brought this intensity to how he got things done."

After the 2004 victory, Rhoades went to work for the Republican National Committee, directing research during a historically bad cycle for the GOP. Colleagues who worked with Rhoades closely during that period — which saw Democrats retake control of both the House and the Senate — describe it as a sort of refiner's fire.

"It sucked," said Jones. "The political environment was awful and it was just not a lot of fun."

"The cycle was a difficult one for everyone involved, and you know, I think many times you learn more in losing than you do in winning," added Danny Diaz, another strategist who worked with Rhoades at the RNC.

It's easy to see how Rhoades would emerge from those years with a bias toward winning races by defining opponents — even at the expense of his own candidate's message. In 2004, Bush won re-election not by wowing the electorate with his record, but rather by defining himself against the flip-flpping Francophile who wanted to replace him. Two years later, the favor was returned, as Democrats rode a wave of anti-Bush fervor into Congress, seizing upon a caricature of the president as dumb, cowboyish, and reckless. This wasn't an era marked by stirring speeches and grand vision; it was dogfight politics — and Rhoades was good at it.

But in the case of Romney's campaign, that approach has come at a price. Large chunks of the Republican electorate remain unsatisfied with the field — many of them supporting Romney only because they dislike him less than his opponents. When they do win, the margin is usually narrow, the support tepid. And on the rare occasions when the campaign reaches for a transformative moment — like the stadium speech at Ford Field in Detroit — it's almost always marred by bad optics.

None of this appears to have deterred Rhoades, who is leaving a host of bloodied opponents in his wake as he guides the campaign to the nomination. Meanwhile, his fierce drive and avoidance of the spotlight have earned wide praise from his coworkers.

"He’s probably the most disciplined and focused person I’ve ever met," said Fehrnstrom. "He’s very committed to whatever task you give him. In the case of the campaign, he is relentless. He lives and breathes Mitt Romney. He never takes a day off, and he gets by on barely no sleep. He’s a real-life version of the Terminator.”