Where To Live

If Snowden wants to stay in Moscow, it'll cost him. The capital — where tepid coffee smothered in condensed milk will set you back $8.29 — was recently named the world's second most expensive city for expatriates in a survey by Mercer.

But if Snowden — who earned as much as $200,000 while an intelligence contractor — wants to test the high end of the market, he could check out vacant apartments at 3 Shvedsky Tupik, or Swedish Dead End. The heavily guarded compound is a stone's throw away from the Kremlin, home to several members of Putin's inner circle, and has two apartments on the market for over a year, yours for only $50 million.

If hearing flight announcements nonstop has left Snowden craving the quiet of the country, he could take after other notable refugees to Russia and move to Moscow's suburbs. Deposed dignitaries like former Kyrgyz president Askar Akayev and the family of Serbian war crimes defendant Slobodan Milosevic live in Barvikha, which has a "luxury village" of fashion retail stores and a concert hall where Simply Red plays seemingly every month. He could also talk shop with another famous former intelligence agent, MI6 defector George Blake, who celebrated his 90th birthday last year in the dacha where he lives on a KGB pension.

Should Snowden opt for the down-at-home pleasures of Russia's regions, he could follow French actor Gerard Depardieu's example and move to Mordovia, a swampy, impoverished province famed for its prison colonies and mosquitos. Depardieu, who received Russian citizenship at a moment's notice and in violation of the country's migration laws in January, is registered as living in a drab, sterile high-rise on 1 Democracy Street in Saransk. If the wooden barns and construction sandlot across the street don't stack up against the view from his old digs in Hawaii, Snowden can trade them in for the mountains in war-torn Chechnya, where Depardieu has a five-bedroom luxury apartment.

Finding a job

Snowden's web savvy and technical expertise should find him plenty of willing employers in Russia, more accustomed to losing top scientists and engineers like Nobel physics laureate Andrei Geim and Google's Sergey Brin. He already has one offer from Facebook clone and piracy haven VK, whose founder Pavel Durov wants to see him "defending our millions of users' personal data." Snowden could feel secure there too. Durov resisted attempts by authorities to clamp down on groups organizing anti-Putin protests on the site during last year's election campaign, and, despite hosting a vast morass of illegally streaming music, movies, and TV, brushed back a suit under a new anti-piracy law Thursday.

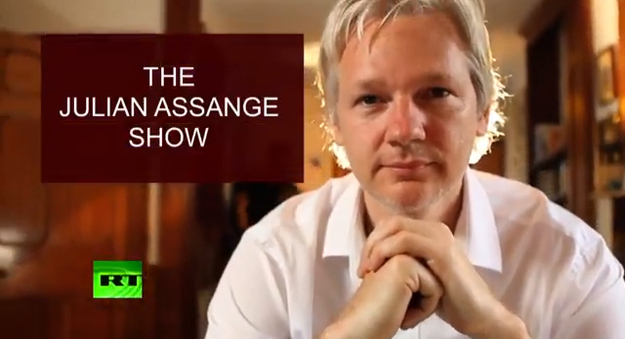

If Snowden prefers his time in the media spotlight, he could apply to host a show on RT. Lavishly funded by the Kremlin and staffed by Russians straining to ape British accents, the network formerly known as Russia Today has won a cult following in the U.S. for hosting guests with views outside the American mainstream. He'd join presenters like WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange and Larry King, who have run interview programs on RT; the granddaughter of Mikhail Gorbachev's foreign minister and the daughter of Russia's ambassador to the U.N.; a former video game designer from Cleveland hired to decry America after the channel saw him report on a provincial cucumber festival; and Brit Daniel Bushell, whose show The Truth Seeker aired a special report earlier this year alleging the Boston Marathon bombings were a CIA "false flag" operation.

Passing the time

Once he finishes the copy of Crime and Punishment his lawyer gave him, Snowden will doubtless be wondering how to while away Russia's long winters other than with its doorstop novels. If ennui and isolation turn him to the bottle, he'll have no shortage of drinking buddies: Russia has the fourth highest alcohol consumption rate in the world, according to the World Health Organization. And never mind forgetting what you drank the night before — as anyone who's seen vodka turn to ice in their freezer can attest, you may not even know what you're drinking at the time.

Or perhaps, after all that time in the transit zone, Snowden would prefer active leisure outside. One Russian vacation destination that might interest him is the North Caucasus Resorts project, a $30 billion plan to draw tourists on skiing vacations to a region that suffered 96 terrorist attacks last year. If he pines for home, he can commiserate with Ramzan Kadyrov next door. The Chechen strongman has welcomed American luminaries like Steven Seagal and Hilary Swank, and can't go to the U.S. either — implications in mortifying rights abuses like kidnapping, torture, and murder reportedly earned him a spot on a visa blacklist.

Staying safe

One thing Snowden certainly won't have to be worried about is Russian security services secretly intercepting all of his communications, since they have legally been authorized to do so since 1995. Though SORM, Russia's equivalent of PRISM, requires a court order to access data from mobile and internet providers, there is no oversight mechanism other than within the security services themselves — and providers just turn the data over when asked.

But he'll run into more trouble if he attempts lifting the lid on Russia as he did the U.S. Fifty-four reporters have been murdered there since the collapse of the Soviet Union, earning it ninth place on the Committee to Protect Journalists' Impunity Index. Whistle-blowers haven't fared much better. Alexey Navalny, who rose to become the leader of the anti-Putin protest movement after exposing vast official graft, was jailed for five years in July after a trial in which the prosecution presented no evidence of his guilt.

A week earlier, a Moscow court found lawyer Sergei Magnitsky, jailed in 2008 after exposing a huge tax fraud involving corrupt officials and organized crime, guilty of having committed fraud himself. But the judge didn't issue a sentence. Magnitsky died in prison nearly four years ago – after what Russia's presidential human rights council found was systematic torture.

But why would Snowden worry about that? He's got a fun life ahead of him.