Freelance photographer Denis Sinyakov was on assignment following environmental protesters aboard the Greenpeace ship Arctic Sunrise as they attempted to scale an Arctic oil drilling rig operated by Russian state energy giant Gazprom in late September. Russian authorities charged Sinyakov and another journalist on board the ship, British videographer Kieron Bryan, with piracy — investigators say they will downgrade them to "hooliganism," though that still carries a maximum seven-year sentence — even though they provided extensive documentation showing that they were on assignment when they were arrested. Sinyakov and the rest of the ship's crew, known as the "Arctic 30," are being held in jail without bail until late November while Russian authorities complete their investigation. Russia has ignored widespread appeals to release the activists and refused to participate in an international tribunal to determine their fate. The Kremlin appears keen to use the case as a benchmark defending their interests in the Arctic, which is believed to hold substantial untapped fossil fuel deposits.

Below are excerpts from a letter Sinyakov wrote while being held in pre-trial detention in Murmansk, in Russia's far north, interspersed with written commentary from his wife, Alina. Sinyakov and the rest of the "Arctic 30" were transferred to St. Petersburg on Monday.

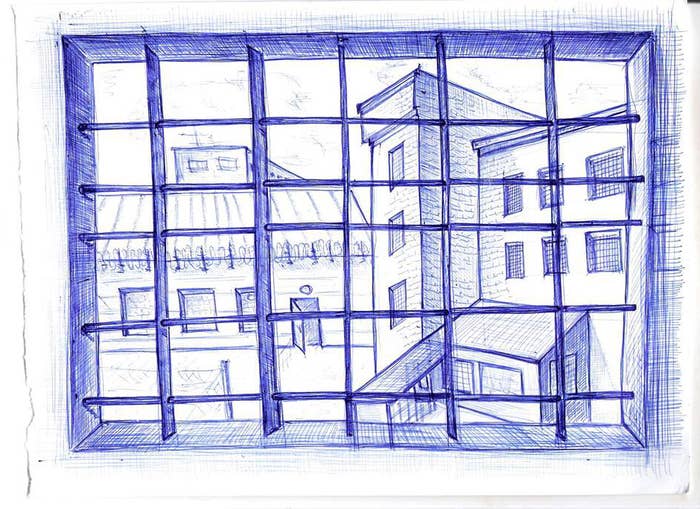

Denis: September 19 was a fine, quiet, sunny day. It'd been 24 hours since the last attempt to send a border patrol onto the Greenpeace boat. The ships were circling four miles around the Prirazlomnaya oil drilling platform. Mark Knopfler was playing from portable speakers on deck. Jon [Beauchamp, one of the activists] was whistling along and gluing together the boats the boarder guards had ripped during a peaceful protest by the platform the day before. I was sitting on the lower deck editing photographs. A siren went out and something along the lines of "Storm coming" came over the intercom. I was taken aback: what kind of storm could there be on such a clear day? But I took my camera and went on deck. I heard the whirring of helicopter rotors I know so well from Afghanistan. The voice on the intercom meant they were storming the boat. It seemed as though only seconds went by before the helicopter's large shadow covered the deck. They threw a rope down from it. The crew ran under it downwind with their hands raised to stop it from landing. But it wasn't planning to: special forces troops started sliding down it like in a movie. I ran around under it and lay down on deck in an attempt to get it all in one shot: the helicopter, which wouldn't fit, the people running around, the armed troopers in masks and helmets, the platform and the border guards' ship with the bright orange sun setting in the background. I ran after two soldiers who were breaking into the bridge. I returned to the crew, already on their knees by now, got hit from behind, and found myself lying on deck with a machine gun in my back. My camera wound up around the neck of one of the troopers and I stayed on the ground with one hand out holding my press credentials.

Alina: I've never been to Paris. I'd always wanted to, but it never worked out somehow. It's not exactly the city of my dreams, but everyone should go once in their life, I think.

And you have to fly to Paris in a romantic mood with a man you love. I've got one of those. But we kept putting the trip off: either the weather wasn't appropriate, or we didn't have anyone to leave our son with, or something else...

Last August I finally managed to win Denis over to the right, romantic thing and convinced him to go to Paris for his birthday. Today's October 16. His birthday. I'm in Moscow. Denis is in Murmansk. He found another excuse not to go! What a guy, huh? How does he manage it? Happy birthday...

Denis:They gave me a piece of paper informing me that I was accused of committing piracy as part of a criminal group. I was sent to a dirty jail for two days. There was a decent policeman who violated regulations by getting me hygiene products from the shop with money they'd taken from me earlier. Thanks to him for that.

All the time until the bail hearing I tried to convince my cellmate, Ruslan [Yakushev] the cook, that this madness couldn't go on forever. They took me to court: the investigator stammered, the judge didn't care what was happening, and I made an awkward speech. I was nervous, even though I'd practiced it the night before. The judge decided on two months in jail.

Alina: Denis and I have a wonderful son, Vasya, who goes to kindergarten. When Denis was charged with piracy and jailed in Murmansk, it was all over every TV and radio station, but the teacher, Elena Nikolayevna, was considerate enough to keep quiet.

The next morning, when I was still half asleep, I knew our son had PE class and got shorts and a folded white T-shirt - the first one I grabbed - from the cupboard. I took him to kindergarten, left his things on the shelf, and forgot about it.

That evening, I went back to get him and asked if there was anything that needed washing. Elena Nikolayevna demonstratively got that white T-shirt from the cupboard and unfolded it to show the print: a polar bear on an iceberg and "Save the Arctic" written below it. Greenpeace gave us that T-shirt in Vasya's size a few months earlier.

The teacher giggled and asked me one question: "Alina, don't you have any other T-shirts in the house?" So everyone knows and understands. But nothing changes.

Denis: Prison's a surprising place. It makes you rethink your views about many things. I'm surprised to see how fellow journalists I don't even know rush to my defense. How entire editorial staffs and TV channels act like heroes. And how, at the same time, my former employers turn into cowardly mice scared of losing their good name. It's a fantastic experience, and I can't help but thank fate for it.

Denis: The appeal. What's the point of this semblance of justice and due process? It's obvious that the judge, prosecutor and investigator are working as one. We have a lovely criminal code, it's a pleasure to read, just a shame that nobody uses it. You need substantial circumstances to justify the harshest of all pre-trial restraints - jail. One of the things they used to shut me up was the evidence of three border guards who told the investigators that the entire 30-person crew was in boats committing a crime. But you just can't fit that many people into the Arctic Sunrise boats! The border guards even gave detailed descriptions of the cook and Katya [Zaspa], the medic, who were asleep.

The judge didn't have any time for the sureties or the bail we were ready to pay. He even forgot to go over the issue of what I was actually doing on board the ship. But he was somehow won over by the investigator's argument that I could escape to Norway, where the ship set out from, even though that same investigator had taken my passport away.

It's like every courthouse I've ever shot. They didn't invent kangaroo courts in Murmansk.

Alina: Murmansk greeted me with snow and cold. It's only October and the city's already up to its knees in snow. Overcoats, puffer jackets, hats, gloves, warm socks. I head to Murmansk City Jail No. 1. I'm terrified. What do I say? How do I support him? What can and can't I talk about? They're listening to us. Got to think. Dogs, tiny windows, men in uniform. They lead me into a little room with a glass window and a phone.

Denis hasn't shaved, but he looks good. We press our hands to the glass, it warms up, we feel each other's heat. I forget what I wanted to say, I lose myself and smile like a fool. I pull myself together. We talk for an hour and a half, I read letters from his mother and brother, I tell him about our life, our son, I show him photographs, then we talk about our friends and colleagues, we try to support each other, make plans for our life...

An hour and a half isn't enough. I really didn't want to say goodbye. We kiss the glass in the same place, it's almost like a real kiss.

Murmansk, October 19, 2013. Translated from Russian by Max Seddon.