Behind Facebook's mobile advertising growth is an unlikely audience: mobile app developers.

Derided during its initial public offering for having no mobile advertising business, Facebook has managed to derive 30% of its advertising revenue from its mobile app in less than a year. A big part of that 30% is from ads that help mobile app developers find new users by showing off their app on Facebook.

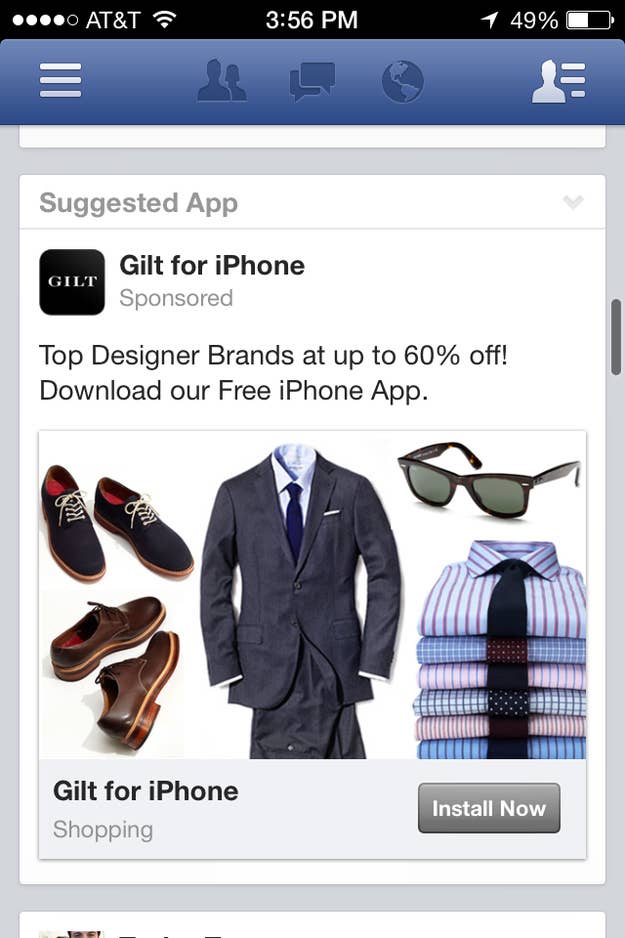

Here's how they work: When an app developer wants to acquire new users, they can start campaigns with Facebook to insert an advertisement in the news feed in Facebook's mobile app that links to where Facebook users can install the app. The developer pays a fee to display the ad in a News Feed. According to sources familiar with the program, the cost to acquire a user through Facebook's App Install ads averages between $2.50 and $3 per install, though it varies from developer to developer. That's a bit of a premium to the industry average (for example, the cost to acquire users through some other providers can be as low as 50 cents). But the combination of Facebook's targeting and the user base on Facebook has made it a favorite among app developers.

Just under 4,000 developers have used these ads, including 40% of the top 100 developers, resulting in about 25 million downloads, Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg said on Facebook's most recent earnings call. For Facebook's business prospects, the significance is clear: Overall advertising growth will benefit from mobile app ad installers since a lot of them are entirely new advertisers to the company, CFO David Ebersman said on Facebook's last earnings call. The numbers back up the claim; while mobile ad revenue represented 14% of Facebook's overall ad revenue in Q3, it was 23% in Q4 2012, and up to 30% in Q1 2013.

The downside is that there is a looming risk of using these kinds of products to "inflate" the size of an app. But Facebook Product Manager Deborah Liu doesn't seem too concerned, saying, "Developers often say, 'We don't want a lot of users, we want the right ones.'"

It also helps that Facebook's premium pricing means that if an app developer wants to game the system, it will cost them.

Facebook lets app developers buy campaigns that advertise the app to relatively specific audiences — a developer creating a hardcore mobile game can advertise to those types of users, for example. The developer essentially serves the ad to the newsfeeds of multiple different audiences and gathers data on which "cohort" — industry slang for the audience seeing the ad — has the highest rate of clicking the ad and installing the app, which ones stick around the longest, and which ones pay for the most products in the app. (This is referred to as the "lifetime value" of a specific user in the industry.)

For instance, the game Dots — a connect-the-dots game that came out of Betaworks — initially acquired a few thousand players using Facebook's App Install ads. That number sprouted to one million in a week, and eventually it climbed to the top of the Apple App Store, thanks to the kind of user base it acquired and the virality of the app. By the end of the month, it reached 3 million downloads. Poshmark, an app that lets women sell clothing to other women, saw similar success from the cohort it acquired on Facebook and now uses Facebook App Install ads as a primary channel for new users.

"You don't really have that capability with a lot of other ad networks. A lot will say you can use 'persona targeting' or something like that, but you don't have clear insight into what that means," Maria Morales, who runs Poshmark's marketing, said. "With facebook you can drill into keywords, see that they've posted keywords, they've liked something, so they have an affinity for that, so you acquire someone who will be interested and loyal to that app."

Facebook doesn't disclose engagement figures for its app install ads, but empirically its mobile users are increasing, and as a result so is the revenue from mobile advertising. As Liu notes, with the number of apps multiplying exponentially, "discovery is a huge problem."

Whether it is "the next app, the one millionth, or 600,000th, they still need to find users," she said. Translation: Finding users means buying advertising, creating a virtuous and recurring cycle for Facebook.

Even Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg seems excited about the opportunity, not just because it fits with Facebook's developer-centric ethos, but also because it almost serves as a kind of community service, curating the million-plus apps on the various App Stores. While Facebook is experimenting with a lot of mobile ad formats — video is an area of interest, based on Sandberg's comments during the last earnings call — Zuckerberg specifically called out the app install ad product.

"One of the developments that's been interesting is seeing how big of an opportunity mobile apps can be for Facebook. Because of the roles Apple and Google have in the space with their app stores, it wasn't as clear early on what kind of a role Facebook would play," he said on Facebook's most recent earnings call. "But I think it's clear now that we can create a lot of value for developers by providing a platform for identity and distribution, and we're starting to see real revenue through selling mobile app installs.

"We just announced the acquisition of Parse, a platform-as-a-service provider for mobile apps, as part of our strategy to provide greater support for developers. Both of these products make it easier for developers to create and grow their apps, and this could be the start of something much bigger."

So, imagine that: an ad product that isn't negatively impacting engagement and almost feels like a community service that can still make a lot of money for Facebook and serves the needs of app developers.