Public fights are a rare thing in the low-key world of professional investment advisers. But as tech startups try to claim their share of the multitrillion dollar industry, they are bringing with them a cherished Silicon Valley tradition: dueling via blog post.

After industry giant Charles Schwab recently unveiled its long-awaited Schwab Intelligent Portfolios product for public consumption, Adam Nash, the former LinkedIn executive and now CEO of online investment advisory startup Wealthfront, blasted Schwab in a post on Medium. "For a young investor, Schwab's greed is expensive," he wrote, before delivering what amounts to the ultimate insult among finance startups: "Wall Street has seeped into every fiber of the company."

The massive brokerage and asset manager responded in a post on its website, accusing Nash of "misrepresenting facts" and saying Schwab has been "at the forefront of driving costs out of the system."

Jon Stein, the founder and CEO of another online investment adviser, New York-based Betterment, also blasted Schwab in an interview with BuzzFeed News.

"When I saw the announcement I was really disappointed, I think the approach they're taking is a step in the wrong direction," he said. "It's unfortunate that they're mistreating customers. I don't want to be painted with the same brush; I think it's important to make it clear to consumers that there are differences."

Both startups say Schwab's product is a raw deal for customers, managing their money in ways that generates more profit for Schwab and lower returns for the client. Schwab, naturally, disagrees, and says the would-be digital disruptors misunderstand the business.

At stake is a question at the core of how Americans invest their trillions in savings: What investment strategies produce the highest risk-adjusted returns for investors over the long term? And there's also the more mercenary question of how investment advisers make their money, and whether they are putting their their clients' interests first. And after all that, there's the matter of whether the massive investment advisory industry can be increasingly replaced by software.

Betterment and Wealthfront, launched in 2010 and 2011 respectively, are small compared to the giants of money management like Schwab or Fidelity: Wealthfront manages over $2 billion worth of assets, while Betterment has $1.6 billion. Schwab manages about $2.45 trillion.

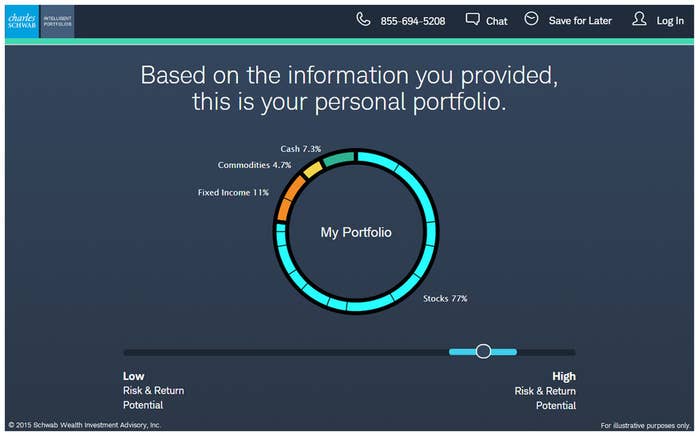

Schwab Intelligent Portfolios uses investor characteristics like risk tolerance and age to automatically create diversified investment portfolios that change over time. It has no advisory fees or commissions, and offers tax-loss harvesting — a formula for selling certain securities to minimize capital gains taxes — for accounts over $50,000.

Schwab's automated program charges no fees, but that doesn't make it free to investors, its competitors argue. Not only do investors have to pay for the underlying costs of the exchange-traded funds Schwab uses, there are also the costs (and gains) inherent to different investment strategies.

Schwab embracing robo-advising, a big development in the advisory business.

Stein and Nash argue that by keeping up to 30% of a client's portfolio in cash, Schwab is causing savers to accept minuscule deposit interest rates over much higher returns available by investing in stocks and other securities. In his Medium post, Nash said a 25-year-old who saved 10% of her $65,000 income each year would end up with $138,000 less by retirement age if just 6% of her savings were kept in cash.

The large cash allocation, Nash said in his Medium post, is indicative of a company looking to earn money not just by managing investments, but also by lending out and earning interest on its clients' money.

"As I was going through the details," Nash told BuzzFeed News, "I started to realize that there was such a conflict between the values I thought Schwab stood for and the actual investment produce." When Wealthfront first hit $1 billion in client assets in June of last year, Nash compared the company to Schwab, writing at the time, "We hope that by focusing on Millennials the way Schwab focused on Baby Boomers, we can continue our rapid growth to $10 billion, $100 billion, and beyond."

Schwab has said that for most investors, the cash allocations will be around 6 to 10%. And "by building in a cash cushion, we think investors will be able to stick with their investing plans for a greater period of time," said Naureen Hassan, the Schwab executive responsible for Schwab Intelligent Portfolios, on a call with reporters to discuss the program.

In a white paper, Schwab argued that having cash in an overall portfolio can provide a damper against volatile assets like stocks and bonds in choppy markets. In recent years, stocks have risen broadly around the world, and keeping savings parked in cash meant missing out on opportunities for higher returns. But in different economic times — say, rising interest rates, or a falling stock market — cash looks a lot better.

"It's easy to question cash in the sixth year of a bull market and when the Federal Reserve is artificially suppressing interest rates, but we don't invest based on the last six years. We invest based on what we expect the future may hold," Schwab said in its response to Nash.

But Nash says that allowing for cash allocations to get so high (the Schwab white paper puts 6% at the lower end), is a disservice to investors that want the lowest cost way to get decent returns.

Schwab is "not alone in using cash to diversify a portfolio," spokesperson Michael Cianfrocca said in an email to BuzzFeed News. "The independent Registered Investment Advisors who custody at Schwab today hold that amount in client cash on average. Many others as well." Independent investment advisers that work with Schwab, Cianforcca said, hold 10% of their client assets in cash.

"I would love to ask Charles Schwab if he has 6% to 30% cash in his investment portfolio," Betterment CEO Jon Stein said.

While Wealthfront doesn't have its own bank, like Schwab does, it still recommends its clients keep their own buffer of cash in an FDIC-insured bank account. Schwab-managed target date funds, which adjust their mix of stocks and bonds as they get closer to the time when clients will start making withdrawals, have varying levels of cash. Its 2020 fund holds 5.91% of its assets in cash, while its 2040 fund holds 3.22% in cash. Vanguard's 2020 fund has 2.24% of its assets in cash.

"The real issue is that the only voices arguing for cash," Nash says "are either active investors or active managers or the company that makes a disproportionate amount of revenue from net interest margin."

For stock pickers and managers of actively traded funds, cash is dry powder for use when prices of assets are below where the managers value them. But for investors trying to track the market as a whole, it's mostly a foregone opportunity.

"The higher the Sweep Allocation and the lower the interest rate paid the more Schwab Bank earns, thereby creating a potential conflict of interest," Schwab said in disclosures filed with the SEC. "The cash allocation can affect both the risk profile and performance of a portfolio."

Nash and Stein see this as a direct conflict of interest: Schwab gets more revenue from its "free" service if more cash sits in client portfolios, and it makes more money if it pays lower interest rates on those cash deposits. Schwab says, however, that interest considerations will not affect its investment decisions.

"These portfolios have been constructed using specific investment strategies that have nothing to do with generating revenue; we are a fiduciary," Hassan said on the call Monday. "That we can earn revenue is a byproduct of how diverse our business is."

The other dispute between Schwab and its competitors is in how assets are allocated to securities. Schwab uses more expensive funds to achieve results it says are superior to buying funds that straightforwardly reflect major indices. It also invests in exchange-traded funds (ETFs) that are managed by Schwab — meaning it pockets the fees that come from running the fund — or from funds the company gets paid commissions to sell.

Wealthfront and Betterment, on the other hand, use exchange-traded funds for stocks and bonds (and for Wealthfront, real estate and commodities), that are almost entirely managed by Vangaurd and iShares. Of the 54 ETFs Schwab is using, 14 come from Schwab itself and eight come from its OneSource program of outside funds sold on commission. "The funds are elected entirely on quantitative criteria with a focus on high quality and low cost," Schwab's Hassan said.

Schwab also invests in so-called "smart beta" or "fundamental index" ETFs that tend to be more expensive. Schwab says that for its allocations to U.S. and international stocks, roughly 40% is put to ETFs that are weighted by market capitalization, and 60% that use "fundamental" strategies.

Fundamental index or smart beta funds are increasingly popular among investors. Instead of simply buying all the stocks in an index and buying them in proportion to how big a stock is, they are tilted toward companies that are smaller or undervalued. These funds have seen massive inflows in recent years, as some investors and academics raised concerns that typical index funds end up overweighting on blue chip stocks.

But these trendy funds are nearly always more expensive for investors than any index-tracking ETF, especially the very low-cost ones used by Betterment and Wealthfront. Schwab's large-company stocks' fundamentally weighted ETF has an expense ratio of .32%, while Vanguard's total stock market ETF, used by Betterment and Wealthfront, has an expense ratio of .05%.

Schwab says its portolios have an average expense ratio ranging from .18% for a conservative portfolio to .26% for an aggressive portfolio. In a moderately agressive taxable Wealthfront portfolio, the average expense ratio, weighted by how much money is allocated to each ETF, is .13%. Wealthfront says throughout its investments, the average expense ratio of its ETFs is .15%.

Betterment's portfolios also have a tilt toward cheaper stocks, but they accomplish it through adjusting the mix of ETFs they invest in. The Schwab portfolios will be able to "exhibit the same type of diversification as institutional portfolios," said Charles Schwab Investment Advisory President Mark Riepe.

Defenders of traditional indexing, like Wealthfront chief investment officer and A Random Walk Down Wall Street author Burton Malkiel, called these funds "a testament to smart marketing rather than smart investing" and called into question whether their historical outperformance persists after fees and taxes. Vanguard founder John Bogle told Institutional Investor that "smart beta is stupid; there's no such thing. It's an idiotic phrase."

"The industry loves to make up new asset classes," Wealthfront CEO Adam Nash said, "because they generate new products to sell."

Wealthfront first launched its service in 2011, not 2007.