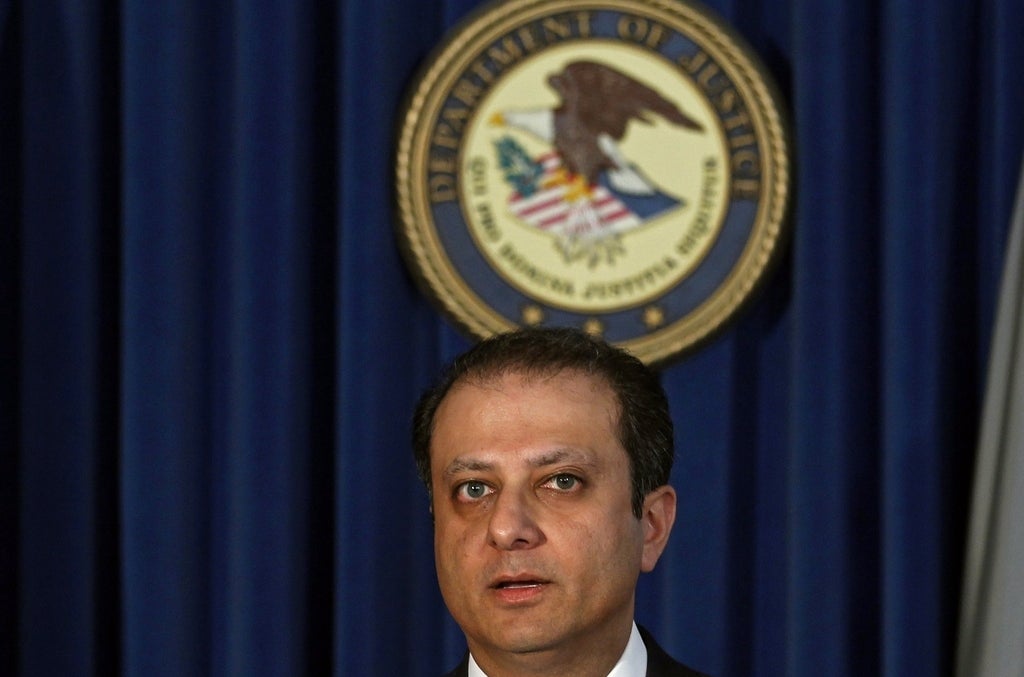

Toward the end of Frontline's To Catch a Trader, the documentary that aired last night about the insider-trading scandal that's ensnared billionaire hedge fund manager Steve Cohen's firm SAC Capital, this question is posed to Preet Bharara, the federal prosecutor who has overseen the investigation: "Do you think you'd ever see a case where negligence rises to criminal liability in the hedge fund world?"

The implication being made by reporter Martin Smith, who was famous for his reporting on Osama bin Laden and the war in Iraq and is now on the white collar crime beat, is clear: There are legal avenues Bharara and other federal prosecutors could be using to advance a criminal case against Cohen, the founder of SAC Capital. (So far, Cohen has only faced civil charges.) And it thrusts Frontline headlong into the well-tread debate over the prosecution of financial crime. Even though overall the documentary is quite laudatory of the FBI and Southern District's pursuit of insider trading, what Frontline is essentially saying is that Bharara is in fact not being aggressive enough.

There's no disputing that Bharara, during his run as U.S. Attorney in the Southern District of New York, has been massively successful at getting convictions against hedge fund managers and consultants it has brought securities fraud and insider trading charges against, winning 77 convictions vs. no acquittals. But the counter argument, which Frontline is subtly advancing, is that his office pursues easier-to-win civil cases and has shied away from bringing criminal cases against bank and hedge fund executives.

This isn't the first time Bharara has been accused of being soft. The most notable past shot across his bow came in the form of a New York Review of Books essay by Jed Rakoff, a Southern District court judge who has heard some of Bharara's insider trading cases and is himself a former Southern District prosecutor. Rakoff speculated that the focus on insider trading had distracted Bharara's office from going after key figures of the financial crisis. "I would venture to guess that the cases involving the financial crisis were parceled out to assistant US attorneys who were also responsible for insider-trading cases," he wrote, and that those attorneys "would put her energy into the insider-trading case, and if she was lucky, it would go to trial, she would win, and, in some cases, she would then take a job with a large law firm. And in the process, the financial fraud case would get lost in the shuffle."

But most experts BuzzFeed spoke with found the position Frontline was staking out to be unusually aggressive and said there was little more that Bharara's office could be doing, particularly in pursuit of Cohen, the founder and owner of SAC Capital whose estimated $9 billion fortune makes up the bulk of the firm's assets. (Cohen was responsible for paying out the $1.8 billion penalty the firm agreed to in a settlement of criminal charges in November.)

"The aggressive posture of the Southern District for insider trading as well as other forms of securities law violations is as aggressive as we've ever seen," said Jacob Frankel, a former SEC enforcement attorney and criminal prosecutor who now works as defense attorney at Shulman Rogers. Most notable is the FBI's use of wiretaps to catch traders receiving proprietary information, a tool generally reserved for terrorism and organized crime investigations.

It should also be noted that, despite his criticism, Rakoff personally knocked down rather significantly the sentence sought by Bharara's prosecutors for Rajat Gupta, the former Goldman Sachs board member who assisted jailed hedge fund billionaire Raj Rajaratnam.

For his part, Bharara responded to Frontline's question by pointing out the wide range of legal tools his office has to go after insider trading — including bringing charges for conspiracy, aiding and abetting, and indicting whole corporations — and said he would "doubt" that there would be a case where negligence rises to criminal liability.

That's because, according to Todd Haugh, a professor at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law and scholar on white collar crime, proving that Cohen — and any other financial manager — criminally failed to supervise employees allegedly engaged in illegal trades is extremely difficult. (The SEC's civil case against Cohen requires a lower standard of proof.)

"[It is] very difficult to have an insider trading prosecution of an individual on a willful blindness theory," Haugh said.

And Frontline has a history of making waves in the white collar crime world. One month after its last major documentary on securities law, The Untouchables, premiered on Jan. 22, 2013, the head of the criminal division of the Justice Department, Lanny Breuer, announced he was leaving the government.

In that documentary, which examined why no Wall Street executives had been brought up on criminal charges following the financial crisis, Breuer gave a now-infamous interview where he said, "I think I and prosecutors around the country, being responsible, should speak to regulators, should speak to experts, because if I bring a case against institution A, and as a result of bringing that case ... it creates a ripple effect so that suddenly counter-parties and other financial institutions or other companies that had nothing to do with this are affected badly, it's a factor we need to know and understand." This was widely interpreted as one of the most senior Justice Department officials saying that large financial financial institutions were "too big to jail."

Breuer subsequently said his departure from the Justice Department had nothing to do with Frontline. But his former boss, Attorney General Eric Holder, implicitly rebuked him in May when he said, "Banks are not too big to jail. If we find a bank or a financial institution that has done something wrong, if we can prove it beyond a reasonable doubt, those cases will be brought."

As Frontline reported in To Catch a Trader, there is still an ongoing investigation into two more suspicious trades surrounding SAC. Indeed, just yesterday jury selection began in the trial of Mathew Martoma, a former SAC portfolio manager accused of insider trading in two pharmaceutical stocks in 2008. Prosecutors allege that Martoma spoke to Cohen on the phone for 20 minutes on July 20, 2008, before Cohen began to unload his position in Elan and Wyeth the next day, avoiding $276 million in losses when the stocks plunged after disappointing clinical trial results for an Alzheimer's drug. Martoma, prosecutors allege, had been tipped off by a doctor involved in the trial that the results would be negative.

Martoma has plead not guilty and Cohen reportedly will avoid testifying by asserting his Fifth Amendment rights. If Martoma sought a deal with prosecutors and testified against Cohen, saying that he had told him the source of his information, then it would likely be Cohen facing trial. But it's the inability to link Cohen to any trades he made with illegally obtained information that has kept him out of court, not any timidity on behalf of prosecutors.