Real film stars know the power of stillness. Often, nothing rewards the eye of the camera — and of the viewer — more than a composed and quiet body whose calm is only an illusion, masking an abyss of emotion, desire, and experience of whatever life the actor has been tasked with stepping into.

Antonio Banderas’s performance in Pain and Glory, a new film by the actor’s lifelong collaborator Pedro Almodóvar, begins with deceptive stillness: Salvador Mallo, a director whose veteran status is announced by the gray in his hair and the slight, middle-aged paunch rounding out his middle, floats at the bottom of a swimming pool in a sitting position, his arms held out and eyes sealed shut. It’s a disconcerting sight, a kind of forced tranquility whose strain is brought to our attention by the magnetic intensity that Banderas, four decades into his career, still emanates.

Pain and Glory (released in March in Spain, and October in the US) is a lovingly detailed cinematic memory piece in which Banderas plays a de facto version of Almodóvar, the legendary director who plucked the young actor from the countercultural theater scene that flourished in post-Franco Madrid. Almodóvar gave him a small part as a horny, baby-faced gay terrorist in 1982’s screwball sex comedy Labyrinth of Passion, a film that marked the beginning of one of the most prominent and productive actor-director collaborations. But aside from the spiky crown of salt-and-pepper hair that adorns his head and the trademark turtleneck he occasionally sports, the actor isn’t doing a mere imitation of his friend. Banderas doesn’t become Almodóvar, but instead captures his inner turmoil.

Salvador has been numbed by a series of maladies and an all-consuming despair. As he resigns himself to a life walled off from the outside world in his glamorous fortress of an apartment — a life of physical deterioration, drug dependence, uneaten meals, departed parents, estranged lovers, spurned colleagues and concerned helpmates, devoid of cinema and any urge to create it — Banderas refracts Almodóvar’s sorrow through an imagined persona that is unmistakably his own creation.

Banderas refracts Almodóvar’s sorrow through an imagined persona that is unmistakably his own creation.

Throughout his career, we have watched Banderas play dashing, goofy, menacing, naive, and smoldering, sometimes within the span of a single Almodóvar film. But rarely has he ever been asked to practice naturalism in his performances, much less the type of becalmed, at times sphinxlike minimalism that the actor achieves in Pain and Glory. Banderas received the Best Actor prize at this year’s Cannes Film Festival and, in the months since, has emerged as a bona fide Oscar contender for the first time in his career. In other words, he has garnered the respect of an industry that has largely failed him.

Hollywood has never really seemed interested in looking beneath the surface of foreign actors like Antonio Banderas. (Banderas, for his part, has spoken openly about his disenchantment with Hollywood. He recently told GQ, “I don't live in Hollywood anymore, but Hollywood is not a place anymore. Hollywood is a brand. And if you are branded with that, it doesn't matter where you move.”) Banderas has always deserved to be known as an actor capable of far more than Zorro and Shrek’s Puss in Boots, the latter part an affectionate parody of the swashbuckling matinee idol persona that seemed to trap Banderas by that point in his Hollywood career. If it isn’t entirely clear that Banderas has always possessed a knack for nuanced, lived-in soulfulness, displayed so prominently in Pain and Glory, then that’s probably because American filmmakers have seldom seemed invested in creating vehicles where such artistry could thrive.

Banderas made his name in Almodóvar’s irreverent provocations of the 1980s, playing stunted man-children in Matador and Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and brutal maniacs besotted with a gay director and a drug-addicted starlet, respectively, in Law of Desire and Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! In these memorable collaborations, Banderas embodied a seductive mix of male vulnerability, perverse desire, and dangerous beauty that fueled Almodóvar’s films and made the actor such a sought-after object of lust early in his career. In the 1991 documentary Madonna: Truth or Dare, the pop icon memorably seethes over coming all the way to Madrid for an Almodóvar party only to find out that Banderas, her celebrity crush, is married.

Not long after this run-in, Banderas parted ways with Almodóvar and ventured stateside for his English-language debut in 1992’s The Mambo Kings, launching an extended stay in Hollywood that, through the ’90s, would see him play Tom Hanks’s chastely devoted boyfriend in Philadelphia, romance Winona Ryder’s Chilean revolutionary in a truly bizarre adaptation of The House of the Spirits, endure as an iconic meme in Assassins, and costar opposite one-time admirer Madonna in Evita. He began a relationship with Hollywood royal Melanie Griffith during the making of 1995’s screwball dud Two Much that led to a nearly 20-year marriage and made the two regular tabloid fodder.

Banderas’s American crossover was solidified with the success of The Mask of Zorro in 1998, but his film career seemed to stagnate in the 2000s, filled with stints in big-budget fare like the innumerable sequels and prequels of the Spy Kids and Shrek franchises. He worked with auteurs ranging from Brian De Palma (Femme Fatale) and Woody Allen (You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger) to Steven Soderbergh (Haywire) and Terrence Malick (Knight of Cups), but the parts were often self-effacing, even when central.

In the past two decades, Banderas seemed to find his juiciest roles everywhere but the movies, particularly onstage — he earned a Tony nomination for starring in a 2003 Broadway revival of the musical Nine — and the small screen, where he played Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa and fellow Málaga descendant Pablo Picasso in made-for-TV projects. His 2011 reunion with Almodóvar in The Skin I Live In, after a break of more than two decades, felt fated but also revealing, an unintended admission that there weren’t any opportunities for an aging Spanish actor in the US that could match the ones back home.

In Pain and Glory, there’s a hushed tension in Banderas’s performance as he buries the heartfelt emotions that we’ve seen him animate in other roles beneath a placid exterior. Salvador refuses — through a sheer lack of hope and energy — to let those feelings see the light of day. And that tension becomes a source of narrative suspense: We eagerly anticipate the moment when Salvador will realize he can no longer bear to carry on this way and let his mask of indifference slip.

There weren’t any opportunities for an aging Spanish actor in the US that could match the ones back home.

Almodóvar directs Pain and Glory with a fluid subtlety that keeps all his actors — but Banderas, as the star, in particular — from overdetermining the meaning of each narrative event. He instead allows them to simply live in the scenes they share. The restraint of Banderas’s approach, in turn, enables Almodóvar to trace the trajectory of Salvador’s depression not with showy gestures but with the unexpected insights that occur in the everyday.

When Salvador reunites with Alberto Crespo (Asier Etxeandia), the washed-up leading man whose ongoing heroin addiction put an end to their partnership, Banderas plays their interactions with a relaxed geniality that deceives us into thinking that Salvador has forgiven his collaborator — until he roundly humiliates him with a too-honest answer during a phoned-in Q&A at a screening of the pair’s last film. It is Alberto who initially provides Salvador with heroin to alleviate his chronic pain, and Banderas even underplays his character’s addiction, disappearing beneath a smiling, palliative fog that lets him sink into memories of his childhood. Depicted in flashbacks, we see Salvador’s mother (Penélope Cruz), who glows with love and devotion, an illiterate laborer and artist who becomes his first object of desire (César Vicente), and the whitewashed cave he grew up in.

In Pain and Glory’s most moving passage, Salvador reconnects one night in his apartment with Federico, a long-ago lover played with profound, true-to-life poignancy by Leonardo Sbaraglia. Banderas is comfortable enough in his stardom to let his performance be influenced and enhanced by his scene partner, whose twinkling eye seems to rekindle a fire that had been extinguished in Salvador. When their characters part ways, Banderas and Sbaraglia exchange a prolonged kiss of sloppy lust, a moment charged by the sight of two middle-aged actors, both straight, abandoning themselves to the needs of their yearning characters. It is sexy precisely because it is a meeting of two bodies that have been weathered by time and the souls that reside inside them.

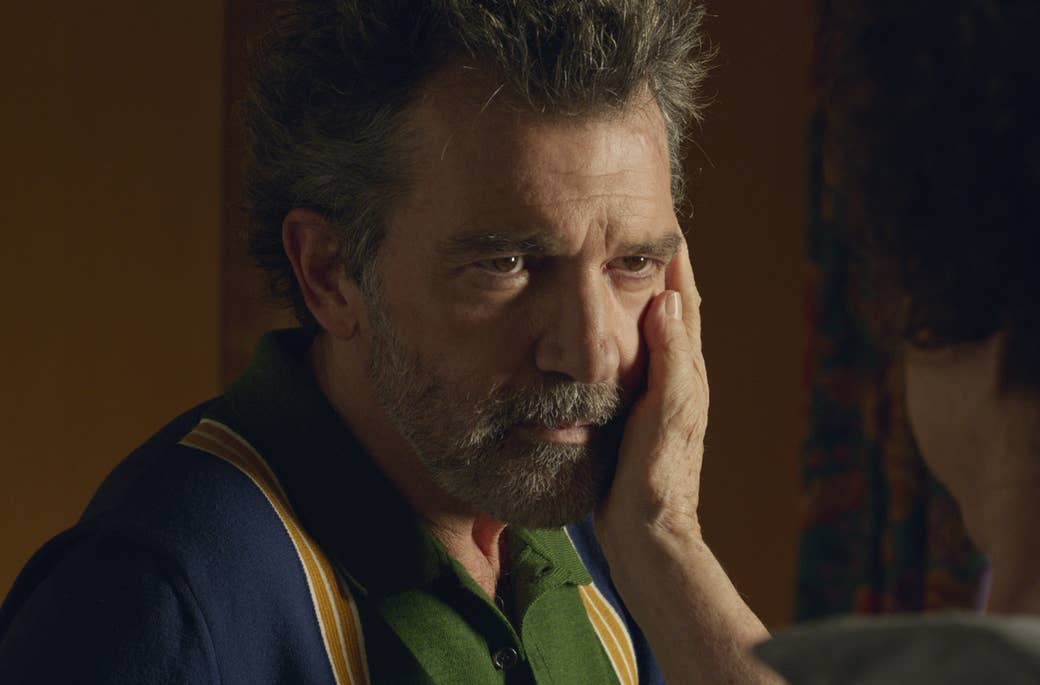

Banderas has always had a formidable physicality onscreen, but rarely has it been harnessed to reveal the psychology of a character. In Pain and Glory, Almodóvar pushes — and trusts — Banderas to use his body to describe the beats of Salvador’s arc without the aid of dialogue. When, immediately following Federico’s visit, Salvador decides to seek help for his addiction, all Almodóvar shows us is Banderas’s face in a thrilling close-up. Salvador’s gaze signals a rush of thought that culminates in an awakening, an acceptance of his inability to cope, which the viewer feels more forcefully in Banderas’s vulnerable eyes than in any possible arrangement of words. Here and elsewhere, the shifts in his face can be so microscopic, as exact as the contraction of his pupils, that they would be undetectable — and their meaning incommunicable — without the presence of a camera.

In their eighth collaboration, the actor and director reciprocate one another’s generosity on the same canvas.

A film as introspective and deeply felt as Pain and Glory could only have been made by a director at a late stage of his life and career, one who knows that we can never really close the shutters on our personal histories. And it could only have been led by an actor who knows that the bulk of his life is behind him, but who also, both onscreen and off, has a great deal left to offer and express. As Salvador gradually awakens from his self-imposed hibernation, Banderas unearths new layers of humor, arousal, and inspiration in Almodóvar’s fictionalized experiences, capturing the fundamental essence of what Virginia Woolf meant when she wrote in Mrs. Dalloway, “The compensation of growing old … was simply this; that the passions remain as strong as ever, but one has gained — at last! — the power which adds the supreme flavour to existence — the power of taking hold of experience, of turning it round, slowly, in the light.”

Banderas reminds us here that there is an actor of rare intellect and sensitivity beneath the widespread image of the winking, slaphappy heartthrob. Playing a version of the man whose career gave rise to his own, Banderas delicately maps out a mind that is always elsewhere, obsessed with a past that is ever-present yet out of reach — except, perhaps, in one’s art. In their eighth collaboration, the actor and director reciprocate one another’s generosity on the same canvas: Banderas gives Almodóvar his talent, discipline, and devotion, and Almodóvar gives Banderas not just a role of great complexity, but a keen understanding that actors contain hidden depths that can only be unearthed by eyes that are willing to see them. ●

Matthew Eng is a Brooklyn-based writer and editor with bylines in the Los Angeles Times, Reverse Shot, Hyperallergic, Little White Lies, Bright Wall/Dark Room, Tribeca Film, and other publications.