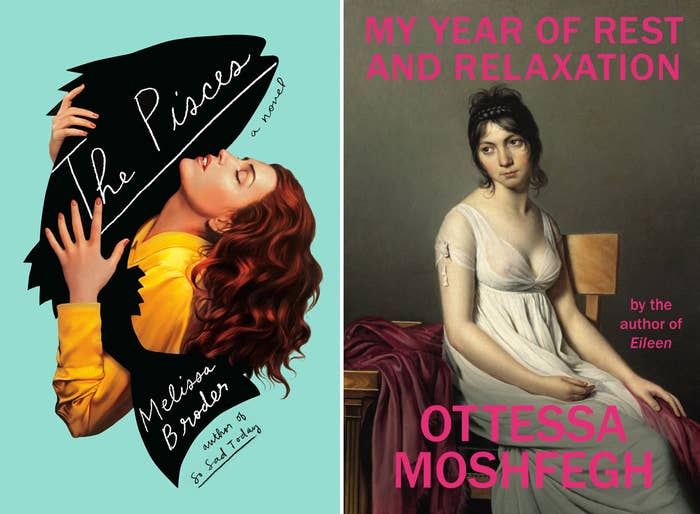

Two of the best books of the summer are pure fantasy, but not exactly in the way of “summer reads” we’ve come to expect: fluffy and sunny and fun. However, it’s fitting that both Melissa Broder’s The Pisces and Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation have been published during a season when readers are typically looking for escapism. Both novels depict women who yearn for refuge from the real world but who choose the worst paths, make harmful choices, and go to dire extremes in order to disappear into their respective voids. It’s jarring to witness boldly self-destructive antiheroines make a mess of their lives, even as the more absurd and delusional aspects of their stories soften the blow of spending time with them. They’re self-centered and negative as hell, but their fantasy lives are too compelling to turn away from. While mitigated by dark humor, very specific pop culture references, and their savvy for observing quite a lot about the worlds they live in even while lacking specific insights into themselves, both characters are still a self-help lover’s nightmare.

The authors of both novels have written extensively about debasement and despair and the trouble with living in a human body. Melissa Broder is a poet and Twitter goddess, best known for her account turned essay collection, So Sad Today, which tackles mental illness and addiction with more candor and humor than you might imagine. In one essay called “Under the Anxiety Is Sadness but Who Would Go Under There,” she says: “On the outside I am smiling. I am juggling all the balls of okayness: physical, emotional, mental, spiritual, existential. Underneath, I am suffocating.” The Pisces, Broder’s debut novel, contains a woman in a similar crisis, but invents a sexy fever dream full of lust and mania to chronicle her story.

Meanwhile, Ottessa Moshfegh has made a name for herself for giving great interviews (“I seem to be attracted to going into the elitist zones, and then, like, farting, and like walking out,” she recently told the Cut) while also writing deliciously repulsive characters. Her Booker Prize–nominated breakout, Eileen, gave us an antihero whose physical ugliness matched her inner life. She, too, is interested in “the idea that [her] brains could be untangled, straightened out, and thus refashioned into a state of peace and sanity,” which she calls “a comforting fantasy.” Her latest novel gives us a traditionally beautiful, unnamed narrator who is just as ugly inside as the rest of the women who inhabit Moshfegh’s fiction, and who would also do just about anything to escape from the misery of every day.

While self-help and wellness culture may be a $3.7 trillion industry, the narrators of these books don’t buy the idea that it will save us. At a time when modern-day women are encouraged to use skin care as a coping mechanism, to do detoxes and cleanses, to cry at SoulCycle, that these characters choose such bizarre, disconcerting ways of coping is in itself a rebellious act. They make jokes as they slowly destroy their lives, make pithy observations as they walk into the abyss. As readers, we witness their systematic destruction like we rubberneck a car wreck, but it’s both disturbing and invigorating to peer directly into the minds of female characters who just don’t feel like trying anymore. That freedom is only accessible via fantasy is further confirmation that women are far from free to simply call bullshit on the world of cheery self-improvement.

There have always been characters who enrich us by being terrible. Unlikable, irredeemable female narrators have long been underrepresented in mainstream fiction, yet Moshfegh and Broder do fall into a lineage of women authors like Kathy Acker and Chris Kraus who have written about difficult, transgressive women. The publishing outfit Emily Books has also spent the last seven years working hard to bring an entire catalog of fiction and nonfiction authors who write about about similarly difficult women to a general audience. These authors mainly focus on women who break taboos by not striving to be better. Or by trying and failing. They’re not trying to learn anything or evolve to become proper heroines; they simply are who they are: terribly flawed, weak, unhappy, angry. Loathe these women and their choices, but it’s hard not to love watching them rebel.

“How had I ended up with these losers? I hated the words they used: inner child, self-care, intimacy, self-love. We were Americans, how much gentler could life be on us?” So says Lucy, the narrator of Broder’s The Pisces. She’s horrified to have landed in group therapy with a bunch of triggered privileged women in Venice, California, after breaking up with her long-term boyfriend and falling into a depression that ends with an unsettling sleep-driving incident: “One night I took nine Ambien. I was not trying to kill myself so much as vanish. I just wanted to go to sleep and be transported into the ether, another world.”

She tries many ways to numb her pain, including New Agey tchotchkes and candles and quartz crystals that offer no helpful effect except for the buyer’s high (“the potentiality of it. I could Capitalist-believe in magic”), and she ultimately finds herself in group therapy hoping to recover from a malady that’s equal parts chronic loneliness, self-doubt, and the yearning to stop feeling so damn much all of the time. Oh, and also sex addiction: “I imagined a bouquet of dicks, a stack of abdominal muscles like a deck of cards, painted across the sky. The hunger in me suddenly felt bottomless. It scared me a little.”

Against the advice of her group, Lucy lands herself on Tinder, hoping for the best but, of course, reeling in the worst. She finds herself going on increasingly humiliating dates and being sexually denigrated in increasingly specific ways. Here she is on a date that was supposed to take place in a hotel room, not the hotel lobby bathroom: “I was fucking on a bathroom floor to ‘Tears in Heaven.’ Sorry, but no. What does it even mean to be alive? I started laughing.” The ladies of group therapy are a messy bunch (“She seemed very Fatal Attraction to me,” Lucy observes about one) but even though they seem destined to fall back into their same old addictive patterns, they’re earnestly committed to the idea of “radical acceptance.” Lucy both pities and is fascinated by these women and by their group leader’s “positivity in the face of the abyss.” The group commends self-dating to recover from sex addiction, a concept that Lucy rejects: “This seemed fucking annoying. I did not want to do any more connecting with myself. In fact I wanted to do less.” Lucy has no intention of doing any form of self-improvement beyond buying some hot and prohibitively expensive lingerie that she wears to her date that ends on the bathroom floor.

It is while dog-sitting for her sister in Venice Beach that she meets a handsome merman on a jetty and gets caught up in the idea of creating a fulfilling life for herself by having sex with a fish. Theo, with his proper male appendages hanging just above his tail, sure seems like a good catch to Lucy: “After all the nothingness, maybe this fantasy was worth living for. I suppose that whenever you’re addicted to something, this is what they mean when they say you forget about the consequences and don’t care about the other side. All I cared about was my plan.” She only has one job, but taking care of her sister’s sweet diabetic pup falls by the wayside as she sinks deeper and deeper into her obsession with Theo. There are so many scenes of her debasement that it comes as a relief to join Lucy in wishful thinking for once, even though it’s clear this story can’t have a happy ending.

Lucy’s desire for oblivion is echoed by the unnamed narrator of Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation: “This was the beauty of sleep — reality detached itself and appeared in my mind as casually as a movie or a dream. It was easy to ignore things that didn’t concern me.” She is young and beautiful and rich, but she’s troubled. Her parents are dead, and her sometime hookup is the kind of jerk Broder’s Lucy might find herself chasing, too. “Back then, I interpreted Trevor’s sadism as a satire of actual sadism,” reflects the narrator on the time they tried anal. “There was shit all over my dick,” Trevor says. She low-key aspires to be an artist, but her job at a Chelsea gallery is ultimately so demeaning that she leaves behind a pile of that same shit before she walks out the door forever.

She embraces total and utter narcissism as a coping mechanism, hoping that sleeping for an entire year would cure her of depression and ennui. “My hibernation was self-preservational. I thought it was going to save my life,” she says. So, in the year preceding 9/11 she takes to her bed, and while she doesn’t fuck any mermen, she does expect that after a year she can emerge reinvigorated and well. It’s just that simple. What could go wrong?

Not a lot, in the world of the novel: “Life was fragile and fleeting and one had to be cautious, sure, but I would risk death if it meant I could sleep all day and become a whole new person.” Moshfegh’s novel portrays a capitalist fairy tale in which a particularly deranged, particularly privileged woman can choose not to care about anything and get away with it. One of the narrator’s best tricks is to acknowledge that her plan could put her in mortal danger, but then she never obsesses about it (even if the reader does). Instead, she watches Harrison Ford and Whoopi Goldberg movies on her VCR all while chewing a wide and assorted variety of pills — ranging from Benadryl to over-the-counter cold medicine to prescribed controlled substances to a few fictional drugs that her quack of a psychiatrist assures will put her “down for the count” — and doesn’t overly concern herself with… anything. She makes the most paltry efforts to maintain a semblance of health. “Oh, sleep. Nothing else could ever bring me such pleasure, such freedom, the power to feel and move and think and imagine, safe from the miseries of my waking conscious.”

Her best friend, meanwhile, is a walking cliché of New York City single lady platitudes at the turn of the 21st century: “She knew all the latest celebrity gossip, followed the newest fashion trends. I didn’t give a shit about that stuff. Reva, however, studied Cosmo and watched Sex and the City. She was competitive about beauty and ‘life wisdom.’” Much like Lucy’s revulsion for her group therapy mates, the narrator of My Year of Rest and Relaxation loves to juxtapose her coping mechanisms with Reva’s. Pathetic Reva, with her drinking problem and bulimia and gym addiction and body issues and neuroses and TMJ from chewing too much gum. Even her kitchen reveals multitudes about her love-hate relationship with herself: “Her cabinets contained exactly what I’d expected. Herbal laxative teas, Metamucil, Sweet’N Low, stacks of canned Healthy Choice soups, stacks of canned tuna. Tostitos. Goldfish crackers. Reduced-fat Skippy. Sugar-free jelly.” Reva is basic at a time when white women doing shallow things doesn’t have a name yet. The alternative, to avoid wellness platitudes and not live up to one’s full potential, is the choice of the two protagonists of both novels, and it’s what makes their journeys so compelling.

How glorious it is to actively choose not to be a Reva. Reva, who would definitely be a Goop subscriber had the novel taken place in the current day. Reva, who puts up with a real asshole of a best friend. Reva, whose striving to better herself would most likely never get her to a place of personal satisfaction. Both The Pisces and My Year of Rest and Relaxation show readers an alternative to trying to fix ourselves all the time. They aren’t pretty, they aren’t recommended, they’re certainly not healthy, but they’re real.

Women are constantly told to “let it go,” but how empowering does it feel — every now and then — to see a woman clutch onto her basest instincts with all her might and refuse to apologize? How rarely do women feel like they have the freedom to wallow? Instead, they’re constantly inundated with new ways to improve themselves — diets, meditations, fitness trackers, serums and vitamins and sheet masks. What a joy, then, to spend some time within a fantasy where a woman can be free of the tyranny of constant self-improvement. ●

Maris Kreizman's writing has appeared in the New York Times, the LA Times, Vanity Fair, Vulture, Esquire, GQ, OUT Magazine, and more.