Carmen Maria Machado is not a licensed therapist or a life coach or a mental health professional of any sort. She is many other things: she’s the writer in residence at the University of Pennsylvania, she’s recently made her debut as a comic book writer for DC Comics, she’s a 2019 Guggenheim fellow, and she’s the bestselling author of the short story collection Her Body and Other Parties, which was a National Book Award for Fiction finalist and is being adapted into a television series. She is known as a genre annihilator who makes the mere act of trying to distinguish between horror and sci-fi/fantasy and literary writing feel petty and irrelevant.

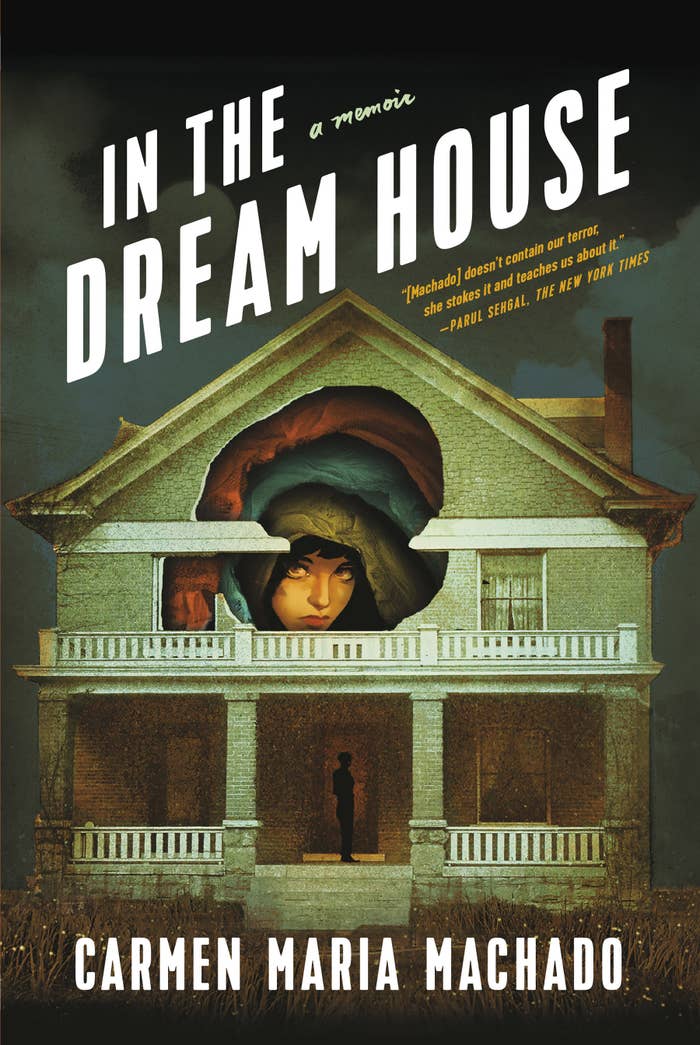

It’s important to have a disclaimer right up front because with her new memoir, In the Dream House, Machado creates a portrait of an abusive relationship that is precise and stylized, but also raw and messy and scary. In describing her year with an unnamed woman who first thrilled and later baffled her, Machado creates an oft-ignored space in the discourse around queer domestic violence. It’s bound to be provocative. But her brutally honest depiction is also bound to hit home, especially for readers who may very well be familiar with the experiences Machado depicts. Even the content of the dedication page gives readers permission to use as needed: “If you need this book, it is for you.”

“I wrote this book because I was looking for something that didn’t exist,” Machado tells me over lunch and rosé at a Philadelphia wine bar in an interview over the summer. “When that happens and you write towards something that’s untapped or doesn’t have art dedicated to it, it creates this new way for people to respond.” Anticipating reader reactions, Machado feels both excited and scared. “I feel like my first book — which was fiction! — loosened something up in people,” she says. “I talked to lots of readers who had a lot to say that they had never felt comfortable saying before. I was grateful but it was also exhausting, and with this new book I’m expecting it even more.” The reaction is a testament to Machado’s ability to make readers feel seen in even the most fantastical of stories, but it also burdens her with the responsibility of managing her readers’ trauma on top of her own.

In the Dream House is Machado’s attempt to document the elation, the confusion, and, finally, the horror of falling in love with an angry and jealous and paranoid woman, a fellow writer, she met while pursuing an MFA from the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 2012. “I enter into the archive,” writes Machado in the book’s prologue, “that domestic abuse between partners who share a gender identity is both possible and not uncommon, and that it can look something like this.” They later carried on a long-distance relationship when Machado’s now-ex was accepted to an MFA program in Bloomington, Indiana, the site of the titular dream house that becomes a symbol for all that could have been and all that went wrong.

What makes In the Dream House extraordinary is that although it does not contain a straightforward narrative, it still revels in placing the actions of the story within the context of longstanding literary traditions. Machado’s memoir is told in fragments, with short chapters that are written around different literary conceits (chapter titles include “Dream House as Lesbian Pulp Novel,” “Dream House as Spy Thriller,” and “Dream House as Choose Your Own Adventure”). It also comes with footnotes that reference folklore and fairy-tale tropes (mother throws children into fire, girl mistakenly elopes with the wrong lover, transformation to stone for breaking taboo). Coming at her subject matter from so many different angles allows Machado to move in and pan out as needed, so that she can document the immediate agony of cowering in the bathroom while her girlfriend pounds on the door, but can also look at the relationship from an intellectual remove. She even makes room for comic relief. “What could seem gimmicky — I confess I braced myself at first — quickly feels like the only natural way to tell the story of a couple. What relationship exists in purely one genre? What life?” writes Parul Sehgal in her New York Times review of the book. There are so many different ways to tell a story, Machado seems to say, but little of what she describes is actually new. Rather, it just hasn’t been widely documented in the pages of the books we’ve been reading.

“The book is also helpful because it’s not just about domestic violence,” says Machado. “It’s about emotional and psychological abuse, which is something that doesn’t get talked about a lot, or is viewed as an experience that’s lesser than, or not real.” Here, finally, is a book that validates such experience. Today, even while critics purport that “cancel culture” has gone too far, we’re still grappling with how to address traumas that are more difficult to label and more difficult to ascribe consequences to perpetrators. It’s a relief to read a book that acknowledges that pain comes in many forms and that such pain is real even if it’s less clear cut.

I want to know how she was able to intellectualize her experience and how she was able to make it beautiful. If I could be one of the first readers to ask her about the book, then perhaps I wouldn’t need to burden her with my own story.

On a sweltering August day I walk from Philadelphia’s 30th Street Station fresh off the Amtrak from New York, past a climate change rally in which teenage protesters earnestly chant and wave signs. Machado, 33, teaches writing at Penn and her wife of two years is a publicist at one of the two trade publishers in town. They have a small but robust literary community in a city still affordable enough that young people — even writers — can afford homes and set down roots.

I meet Machado at a Center City restaurant that she’d suggested for lunch, but it’s stuffy even inside the air-conditioned space. So we sit there with sweat dripping down our temples while fanning ourselves with lunch menus and waiting for more water to arrive. I’m already eager to grill her — I want to know about how she first started circling around the idea of writing about her abusive relationship.

“For years I tried to write about what had happened,” she tells me, “and I was bouncing off the material. I was trying to write a linear story and it never quite synced up in the right way.” To the point, she says, that when she returned to writing this book, she thought she should go back to her earlier work from grad school try to harvest some material. “But there was nothing I could salvage,” she says.

After reading Machado’s memoir, I went back and reread her previously published work with a different eye, and it became clear that she’s been thinking about telling this story for a while. “Mothers,” a story in Her Body and Other Parties, reads completely differently now. In it, a woman and her ex, whom she only refers to as “Bad,” fantasize about living in a beautiful home (a dream house, if you will) and perhaps one day having children. In the story, Bad hands off a strange baby to the narrator, claiming that it’s theirs, and then Bad deserts her. The fantasy becomes a nightmare as the narrator thinks back on the ways Bad has abused her.

There’s also “Blur,” a story originally published in Tin House Magazine that Machado had contemplated including in Her Body and Other Parties but later decided it was too similar to “Mothers.” “Blur” is the story of a woman who loses her glasses in the bathroom of an Illinois rest stop on the way to visit her girlfriend in Indiana. Terrified to call her girlfriend and face being yelled at and belittled for her mistake, the narrator sits in the parking lot until she meets a mysterious man in blue who suggests that she simply start walking to her girlfriend. “Walk from here?” she asks. “Sure,” he says. “That’s proof that you love her, if you come toward her on your hands and knees.”

"Everyone knows what it’s like to be in a situation and not realize what you’re in until you’re up to your neck in it.”

Working within the constraints of short fiction allows Machado to put one foot in front of the other in her writing. “Sometimes stories just need something to hold on to, and form is a way of doing that. Sometimes you’re looking at a story and you’re like, What comes next? But if I say I have to add an item to the list, another lover or an episode of SVU,” as in her tour de force story from Her Body and Other Parties called “Especially Heinous,” “it’s easier.”

Structure can make stories come to life in ways that traditional narratives can’t. “There’s all kinds of ways to give a story a constraint or weight that lets it be really interesting,” Machado says. “My favorite stories are list stories or fragmented stories, stories that are in pieces.” This narrative freedom allowed her to construct intricate, weird, multilayered stories even while dealing with the trauma of her dysfunctional relationship.

But Machado tells me that she’d attacked her relationship through fiction as much as she could. “With this book,” she says, “I felt that if I zoomed in on one thing, I could talk about it, but trying to talk about it in a bigger way would be too hard.” In fact, Machado went through a period of creative fecundity by embracing working with fragments of stories rather than trying to focus on the big picture. “It could have really shut me down,” she says, “but I was just firing. For me things only made sense in pieces.” In a chapter in her memoir titled “Dream House as Exercise in Style,” which takes readers through her process of crafting her story collection, she writes, “I broke the stories down because I was breaking down and I didn’t know what else to do.”

In 2015 she used an approach similar to writing her memoir, giving readers glimpses into short scenes in her life and her work that add up to feel expansive. “I think ‘haunted house’ was the first thing I conceived of,” she says. “I had a little notebook and I made a list of all these different conceits and structural possibilities.” She mentions seeing a reader review for Her Body and Other Parties that asked, simply, “Why can’t she just tell a regular story?” “And I thought, good question!” she says. “But ultimately I think that’s how I managed to write the book.”

The structure of In the Dream House matches Machado’s experiences as a queer woman in an abusive relationship. “It didn’t fit into a neat narrative,” she tells me. “We like things that we can easily label. It makes people uncomfortable not to know.” She echoes a part of her memoir when she tells me she wishes her ex had been a man because it would’ve been so much easier to explain. “Or I wish she’d hit me because we have narratives for that. I wish she was a man who’d hit me because that is a very exact scenario, very clear.” It’s easier for people to ignore if they don’t have the cues to see what’s happening right in front of them.

Here’s where I break the seal and start to cry a little. I’m happily married to a wonderful man now, but I was once with a man who I wished would hit me so other people could see and understand what I was going through. My body was wracked with pain from anxiety and fight-or-flight hormones, but you could not see any bruises. I can’t resist taking a turn to talk about my own experiences with Machado, as I imagine so many future readers will do as well.

I tell her about a few moments, like the day when this man and I were casually talking and he said, “Sometimes I lie about little tiny things just because. Like, little things that don’t matter.” I went back to him about two years later after he’d told me a number of lies — big and small and in-between — and I said, “Remember how you told me about how you lie about little things?” And he said, horrified, “No, I never said that.”

“Carmen, how could he be so textbook about gaslighting me?” I said, knowing, or hoping, that she would understand.

“There’s something so dark and weird about what a cliché it is,” she says. “And it makes art harder because it’s like how do I turn this thing that operates on cliché — its life blood is the cliché — and create something interesting from this incredibly dead thing? If you say it’s as hot as an oven, your brain skips over the phrase, it’s so worn. And that’s what makes cliché so dangerous. If you say it enough, you lose your ability to engage with it in any kind of critical capacity.”

“I’m not obsessed with him. I’m obsessed with what I let happen to me. Because I should have known better,” I say, looking to Machado for guidance even as I realize that “should’ve known better” is one of the worst clichés there is.

“But even in the most classic presentation of domestic violence, everyone knows what it’s like to be in a situation and not realize what you’re in until you’re up to your neck in it,” she says. “That happens with jobs, that happens with family relationships and friendships. Judgment is deeply unhelpful. Would you say ‘you should’ve known better’ to a friend? Of course not.”

She takes a sip of wine and says, “You couldn’t have known better. How would you have known?”

Machado’s demeanor visibly changes when she talks about her wife. She warns me right away that she won’t talk too much about her, but it’s a relief to get to a happier subject.

“She has always been my first reader,” says Machado. But this time, Val is a character in her book and therefore she couldn’t take as large a role in the writing and editing process. She did eventually read it, and Machado tells me she loved it. “But I went through this phase where I was like, ‘Does this suck?’ and normally I’d give it to her and she’d give me her thoughts, and I couldn’t do that this time. With fiction it’s really nice because she’s also a writer so I’ll send her work and she’ll send work to me or we’ll read it to each other. It’ll be like a prize: ‘If I finish writing this thing today, I’ll get to read it out loud.’”

As she tells me this, I think: Has the act of reclaiming a narrative ever felt so romantic?

“We also love each other’s work,” she tells me. “I don’t think we could be together if we didn’t love each other’s work. When I broke up with my ex, everyone was telling me to never date a writer again, but now I can’t imagine it any other way. It turns out it’s not about a writer, it’s about finding the right person. Writers can be great or terrible, depending on the person.”

"People get very fixated on ‘We need evidence, we need a police report, we need photos.’ Sometimes it’s not that simple. It’s never that simple.”

Even now that she’s in a happy and fulfilling relationship, Machado’s experiences with her ex still color how she sees the world. She tells me a story of a night when she and her then-future wife were visiting a friend in Boston, at a gay bar that was having a lesbian night. The friend had arrived early, so she and Val stood in an interminable line outside for so long that they never made it inside. But there was a fight taking place behind them. “We could hear this low hushed argument happening, and then it escalated quickly,” Machado says. “One of them ran out of the line and got into a cab, the other one followed her and was pulling her out of the cab. The whole time this was happening, we were gripping each other’s hands so hard because there was something about it that felt so familiar.”

“It triggered every cell in my body,” she says. “I felt for this girl. When you say ‘you can just tell,’ it’s hard to explain. People get very fixated on ‘We need evidence, we need a police report, we need photos.’ Sometimes it’s not that simple. It’s never that simple.”

I ask if she thinks her ex will read the memoir and if she’s considered how her ex might react. Succinctly and decisively Machado replies, “I don’t care what she’d think of the book.”

While we do not talk about her ex again, we do talk about consequences. There’s a chapter in the memoir called “Dream House as Epiphany” that consists of a single line: “Most types of domestic abuse are completely legal.”

So how do we talk about consequences for abusers who haven’t done anything illegal? “Well, we can’t put them in emotional abuse jail,” she laughs. “In a just world, people could speak about their experiences in an honest way, in a way that makes patterns easier to establish, and people who’ve been abusive can at least be confronted by what they’ve done. That seems fair to me.”

The discussion of punishment is in the air now more than ever because of #MeToo, and there are no easy answers for all of the gray areas that have come out of the movement. “We’re very clear-cut on rape,” she says, “but what does it mean if someone just says something suggestive and weird? I don’t know if there’s a solution to that.” It would be helpful to know if the perpetrator has some sense of remorse for what they’ve done, but that’s not provable. Ultimately, she says, “You have to be comfortable with the ambiguity of knowing that people do bad things and they get away with those bad things and that’s just the world we live in.”

“But it’s okay to say, ‘This is what happened to me,’” she says. “I don’t have an answer, I don’t know what the punishment should be. But I can say that something happened to me and no one can take that away from me.” If someone asks her what she would do in a particular scenario, she’d say, “I don’t know.”

“I have to practice saying ‘I don’t know.’ I just hope I can help people feel supported to tell their own stories.” This feels like a great note on which our conversation could end, but then Machado can’t resist: “And if one person reads this book and tells their shitty boyfriend or girlfriend to fuck off, then great.” ●

Maris Kreizman is the host of a literary podcast called The Maris Review.