Dr. Michael Salzhauer, 44, sits at a chunky wooden dining table in his cavernous Mediterranean home north of Miami Beach. We’re surrounded by “barters,” as he calls them: curtains, furniture, jewelry traded for nips and tucks. “My wife needed a bookcase, and the decorator said, ‘I know this great guy who makes bookcases.’ So we traded: He built that,” he says, gesturing at the built-ins spanning one of the great room’s walls, “and I'm doing his wife’s tummy tuck in a week.”

On this evening in late March, we eat lasagna on dairy-only placemats atop a meat-only tablecloth an arm’s length from his kosher kitchen. His five kids have been shuffled to the other side of the house, shooting hoops on their indoor court emblazoned with a Miami Heat logo or playing on their phones. The youngest has spelling homework due tomorrow, and is begging his mother, Eva, Salzhauer's wife of 21 years, not to make him study (“The teacher never checks — there’s no point!”). After dinner, Michael will head to evening temple services to pray for his father on the 16th anniversary of his death.

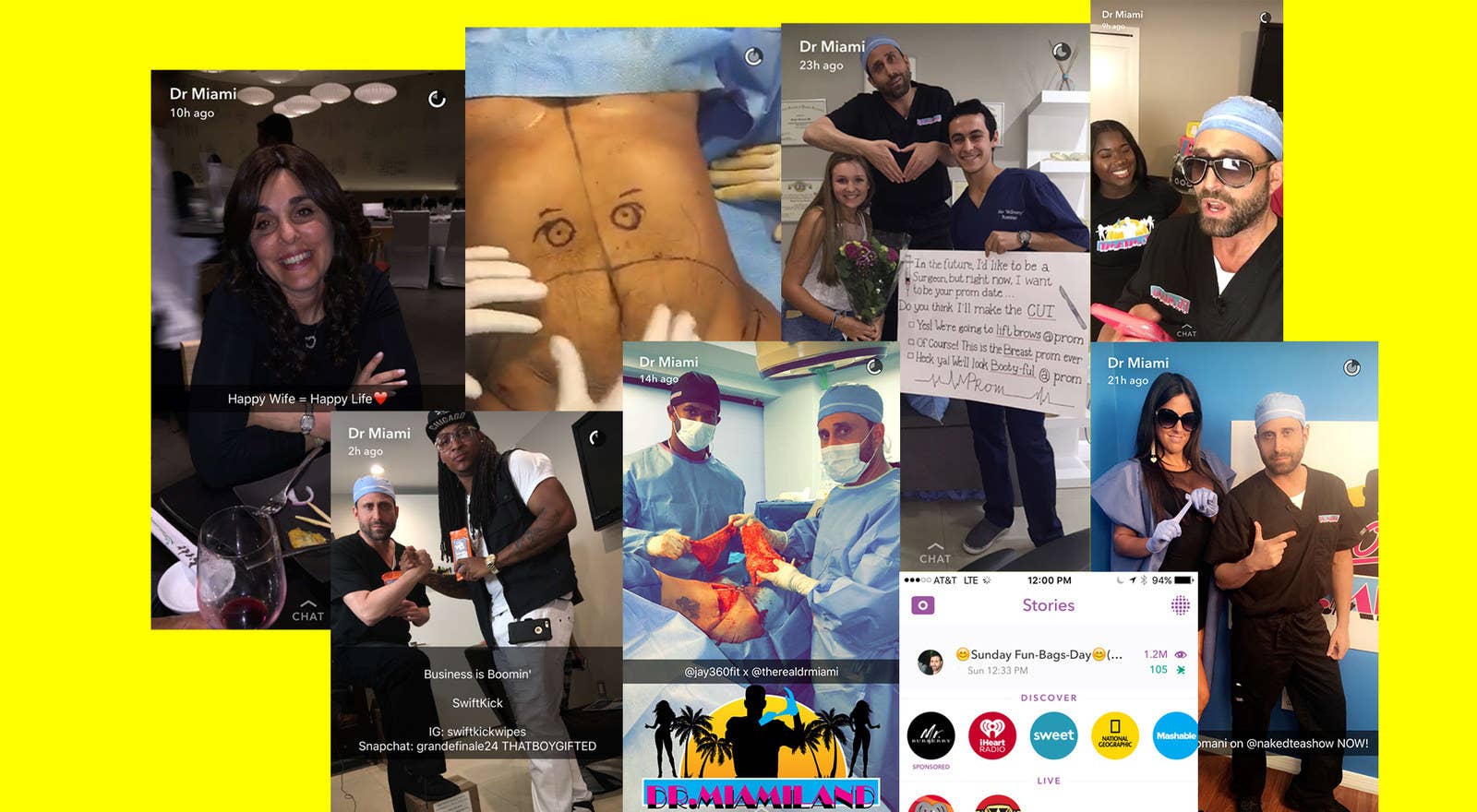

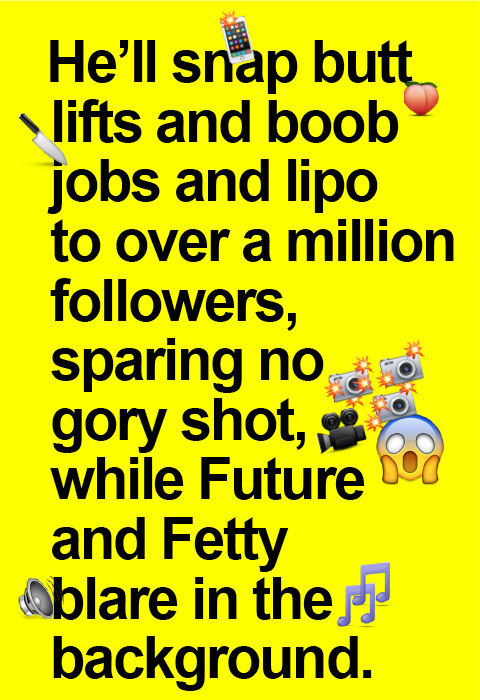

An Orthodox Jewish, Floridian dad may seem like the unlikeliest star of a platform targeted to teenagers. But early tomorrow morning, under the too-bright Florida sun, Salzhauer will drive through his tony neighborhood to a nondescript office building, pull out his phone, and become Dr. Miami, one of the biggest stars on Snapchat. He’ll snap butt lifts and boob jobs and lipo to over a million followers, sparing no gory shot, while Future and Fetty blare in the background.

Here’s how it works: Dr. Miami operates on patients — 90 to 95% are female — willing to have their surgery broadcast; 2 out of 3 agree to go on camera and, no, they don’t get a discount. The doctor explains each slice, suck, and suture as he goes, while a social media assistant documents it on a cell phone. The grisly videos and photos are posted to Dr. Miami’s Snapchat Story (@therealdrmiami), which users can view for 24 hours. In between surgeries, he posts spontaneous clips of life at the office, and he ends each day with shout-outs to viewers who message him.

“He likes to be the showman,” Eva tells me, carrying an unsolicited bowl of cut fruit to the table. “The only thing that's new for me is that so many more people are noticing.”

Since he started snapping a year ago, Dr. Miami’s audience has exploded at a bacterial pace. At first a single post attracted 2,000 viewers; just a few weeks later, 30,000. The Wednesday I arrive in Miami, he’s averaging 800,000 views per snap. By the time I land back in New York, he breaks 1.2 million views on one called “Sunday Fun-Bags-Day,” and has since hit 1.7 million on a single post. His viewership peaks at the week's start and drops by around 100,000 as the week goes on; he thinks it’s because he's offline for the Sabbath every Saturday, so fans are hungry for his posts by Sunday.

He was nominated for Snapchatter of the Year alongside Kylie Jenner and fellow Miamian DJ Khaled. Director Marc Klasfeld, whose video for Wiz Khalifa’s "See You Again" recently broke a billion views on YouTube, asked him to collaborate on a project. Tabloids like Us Weekly and Bossip covered him for Twitter feuding with Nicki Minaj and doing “mommy makeovers” for Teen Moms and Bad Girls of the titular club. Fans come from all over the country to take selfies with him, including a superfan who drove 18 hours from Alabama the week I visited. (Technically, her family drove; she wasn’t yet 16.) He receives near-constant media requests and pitches for reality shows, one of which is being produced to air later this year. In the meantime, he's hosting a Facebook Live talk show called Naked Tea, in which he and his staff talk celebrity news and interview local guests, like Real Housewives of Miami's Lea Black.

It’s the kind of attention he’s been chasing for years. He was voted class clown in his medical school yearbook. He put his face on bus stop ads. “When he first became a plastic surgeon,” Eva says, “he was the only plastic surgeon that hired skywriters.”

Then a tireless string of gags called out as gaffes, including a 2008 children’s book about plastic surgery called My Beautiful Mommy; 2009’s surgery simulation app iSurgeon; 2010’s Heidi Montag–inspired game Heidi Yourself ("If we had known about it, we would've def sued that idiot," Montag’s husband, Spencer Pratt, told me); and a 2012 music video called “Jewcan Sam (A Nose Job Love Song)," which was condemned by the Anti-Defamation League and prompted an investigation by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

But transitioning from Dr. Salzhauer to Dr. Miami has done wonders for his career. Dr. Salzhauer did good work but got some bad press; Dr. Miami is a role model, with patients so eager to see him he's booked for the next two years. “He's not a crazy person,” Eva says. “He's a real person with a real profession. It's nice that people are looking up to someone other than some drug addict.”

Plus, he insists, he’s fighting the stigma surrounding plastic surgery while getting kids into medicine. “I think it's really tyrannical to tell other people that it is wrong for them to want to look a certain way or do a certain thing,” he tells me, picking watermelon slices out of the bowl with his fingers. “That's their choice. Especially since they do look better.”

“Better?” Eva scoffs. “Some people look like different human beings.”

He Skypes into medical school classes, answers viewers' questions, and sells suture kits to teenage fans who want to stay in school and become surgeons because of him. “I think about Michael Phelps and I think rising, rising, rising, and then...” He makes a fist and pops it open, making a noise like a bomb going off. “People like to build up their heroes and then crash them down.”

His son, David, 11, interjects: “It's gonna last for a long time, though.”

“You think so?” Eva asks.

“People who are famous are famous for at least 10 years,” David says, and pauses. “I think I'm gonna take over. But I'm not gonna be the same. I'm gonna do something else that's gonna make me famous. If you're a Salzhauer, you can do anything to make you be famous.” He reaches over toward his dad for a fist pound.

“All right,” Salzhauer laughs. “That's the first I've heard that one.”

“You can make yourself famous for anything,” David says, chewing on a noodle like it’s bubble gum.

Eva sighs. “Let's not become infamous, though.”

“So, how are you with blood?”

It’s one of first things the doctor asks me when I arrive at his clinic on Wednesday afternoon. He has a chiseled jaw and an artificially chiseled nose and makes intense eye contact always, breaking only to assess whether I’m wearing appropriate shoes.

He is wiry and kinetic, speaking screwball-fast and always on his toes, wearing black scrubs featuring a neon “Dr. Miami” in the Miami Vice font. The logo is everywhere: in the elevator bay, on the walls, on his employees’ shirts (which fans may buy through his online store — called alternately the Booty Q or the We the Breast Store, a play on DJ Khaled’s We the Best Store).

“OK,” he tells one of the receptionists, clapping his hands together like a kids soccer coach. “I’m going to bring her down to surgery.” He skips the elevator and instead sprints down the outdoor stairwell overlooking the parking lot.

The Bal Harbour Plastic Surgery office, all clean gray stone and jewel-toned Home Goods accessories, takes up three floors of the Kane Concourse building on the island of Bay Harbor. It’s in a ritzy area, 30 minutes north of South Beach, home to Israeli-born Miami Heat owner Micky Arison and a synagogue undergoing a $20 million expansion. While they wait for their consultations, Dr. Miami’s clients are encouraged to pop into the nearby luxury mall or sun by the beachside Ritz Carlton.

“Today’s patient is getting an unusual procedure for Miami: an implant reduction. Her husband wants them to be smaller,” he says as we walk and talk through the OR prep room while a Barbie-incarnate nurse hands me a smock, hairnet, and booties. “I don’t know if she’s embarrassed or what, but she came in saying she was unhappy.” He sighs. “Sometimes I’m a psychotherapist with a knife.”

The social media assistant on duty is Ashley Belance, a 21-year-old Florida native who started working for Dr. Miami about a year ago. At the time, she was working overnight shifts at a South Beach Marriott, while taking online classes and raising her 3-year-old son. One restless morning after work, she was lying in bed and saw the job posting on his Instagram. “I took a screenshot of it and I sent it to my friend and said, ‘I’m going to work for this man.’” She was the first social media assistant Dr. Miami hired, followed by Brittany Benson, 27, a college athlete turned HR specialist turned model. They film the procedures, but are also characters on the “show,” as they call it.

Once Ashley enters the OR, she opens HotNewHipHop on a desktop while the doctor and an all-male surgery team assess the anesthetized woman lying on the table. He takes two steps toward a monitor displaying her name and “before” photo, and asks Ashley to cover the name with medical tape. She does, then shoots the doctor explaining what procedure he’ll be doing today.

“You know, kids, what I always say is, ‘If you can change a tire, you can change an implant,'” he says as he prepares to slice around the nipple, sounding like the biology teacher on an alternate-universe Disney sitcom. “I take my 15 blade, go across the previous incision here. I cut the breast tissue carefully into the implant pocket, take the old implant out, and put the new implant in.” Ashley leans directly over the table, positioning herself to get every visceral detail. The smell of burning flesh hangs in the air. There’s some disagreement about songs, what they have or haven’t played recently, what viewer song requests still need to be fulfilled.

Ashley doesn’t film everything — these procedures can take anywhere from 30 minutes to six hours. It’s more like a cooking show, where Martha Stewart stuffs the chicken, says it has to bake for two hours, and magically pulls a completed one out of her oven. Dr. Miami and his team work with Olympic precision but banter like any other officemates: Ashley wants a new car, and the guys rib her for her current one, a Hyundai. They joke about driving a stolen one up from Mexico.

It’s been a few minutes since they last posted, so Dr. Miami requests some screen time. “I stand corrected,” he says, speaking faster than Mavis Beacon types to meet Snapchat’s 10-second time frame. “It's not easier than changing a tire at a NASCAR pit stop. It's faster than changing a tire on the road like an average person. I apologize to any NASCAR fans who said, 'Hey, it takes seven seconds.’” He searches his name on Twitter for reactions, and checks how many screenshots his Snapchat viewers have taken (1,000-plus signals success). Often, the more childish the image, the better: A recent hit was someone’s stomach, mid–tummy tuck, gaping open like a smiley face with two eyes Sharpied on, with the caption “Don’t worry, be happy.”

For the final shot, the doctor grabs the phone from Ashley. He points it at the “before” picture shown on the monitor, then at the “after” lying on the operating table. “So we're all done. Implants are changed. See?” he says, poking at the right breast. “It's like we were never there.”

“In the beginning, my daughter was amused,” he tells me post-surgery, as we settle into his private office. “She’s the one who first told me about Snapchat.” His office is cluttered with stuff: medical books; a soft box to light his videos and Skype consultations; a clear plastic bag holding tefillin for his morning prayers; clippings of his appearances in tabloid magazines; a fake People magazine cover featuring him and his wife (“Famous Couples: Their Secrets Revealed”); and a prototype for a failed crowdfunding project, a doll with interchangeable boobs and butts.

A little over a year ago, he’d attracted around 90,000 Instagram followers posting before-and-after photos of his handiwork. But the platform is notoriously sensitive to nudity, and deleted his account after one risqué photo too many. That’s when his then-15-year-old daughter suggested he try Snapchat. “She goes, ‘Dad, 1,800 people watched it — that's a lot of people for a Snapchat. I usually get three.’”

With the help of his sister-in-law turned practice manager, Rosy Zion, and one of his young employees, Tati Pinzon, he kept pace. A few weeks later, his following was in the tens of thousands. From the start, his Snapchat fans weren’t just talking about the quality of his surgeries, but that he was the dude who goofed around listening to hip-hop during them. After a viewer first requested he play “Trap Queen” during a procedure, Fetty Wap became a foil for the doctor: Dr. Miami sent his fans on a faux mission to get a 43rd birthday shout-out from the rapper; on Fetty’s birthday, the doctor posted a "tribute” video to YouTube in which he played a piano cover of “Trap Queen” à la Ben Folds. The gimmick earned him fans, especially among teenagers. He recently added a “Trap King” shirt to his online store.

It didn’t stop with Fetty. He refers to himself as the Jay Z of his own little empire — he sometimes uses the rap name Hndrd — which as of late includes SurgRecordz, a record label seeking new artists to play during his surgeries and give exposure. He’s friendly with black reality celebs (he recently redid someone’s butt on an episode of Black Ink Crew). A recurring narrative on his channel involved his hunt for a pair of Yeezy Boost sneakers, which he ultimately received in exchange for a half-price butt lift. He throws up deuces with sliced-open bodies and told Complex he likes to operate to Lil B and “Bitch Better Have My Money.”

And yet, he makes dated pop-cultural references the young women on his staff don’t get: MASH and Love Connection and Mikey from the Life Cereal commercials. His open tabs include a Reddit “Joke of the Day” thread he uses to crib material. When he is asked to submit a prewritten speech for the Shorty Awards, he googles “funniest acceptance speeches,” so he can drop in a link to that in lieu of writing his own. For religious reasons, he doesn’t allow TV in his home, but dreams of a cameo on Saturday Night Live and working with Adam Sandler.

He isn’t cool. But fans like the character he plays. Every patient who comes in while I visit the office is black or Latina, and comments on how much they love his music, his attitude. To them, it’s not an act — he’s a talented doctor who feels secure enough to be himself, which in turn makes them more confident in his abilities. They trust him, and as a result he’s booked out so far in advance, consultations are now walk-in only.

When I ask why he thinks he resonates with black audiences, he makes an awkward joke — “Because I'm black. You can't see? Racist!” — but shakes it off. “I think surgeons are probably the least racist people on the planet,” he says, “because we see people literally without their skin. And we know that we're all the same.”

Madeleine Salazar, a 24-year-old Venezuelan-American receptionist with Phish ephemera thumbtacked around her desk, notes that as Snapchat has gone berserk, the office has attracted an increasingly black clientele. The doctor used to do so many rhinoplasties he was dubbed “Dr. Schnoz”; now his focus has moved south. And it isn’t just his practice where things are changing.

“Thin is always in, but now you also have to be thick,” says the receptionist, who used to think plastic surgery was “weird,” but is now staying in her job to get free lipo from the doc. It’s an observation affirmed by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, which reported that butt lifts are among the fastest-growing procedures in the United States, up 252% since 2000 (rhinoplasties, meanwhile, are down 44%). Dr. Miami says he does 500 Brazilian butt lifts a year, in which he liposuctions fat from other parts of the body and injects it into the butt.

“I think it’s celebrities,” she explains, packing purchases from the Dr. Miami store in shiny pink shipping mailers as we talk about the rise of the big butt. “And I also think it’s hip-hop and African-American culture becoming very mainstream. They’ve always been like, ‘Thick? Yes!’ And now everybody wants to be thicka than a Snicka.”

Snapchat isn’t the first time Dr. Miami has brought a camera into the OR. It isn’t even his first attempt at viral fame. “In the past four years, he's racked up more controversies than Lindsay Lohan,” the Miami New Times wrote in 2012. His antics made him seem like “a pantomimic villain: the flashy, heartless, obscenely wealthy Miami plastic surgeon. Salzhauer hardly tried to counter the image. Instead of backing off, he's doubled down with increasingly outrageous videos, openly pushing for ever younger patients to go under the knife.”

His first brush with infamy was in 2008, when he wrote the children’s book My Beautiful Mommy, which chronicles a child learning why her mother got plastic surgery. “I got a taste of blood there,” he says, sitting at a desk cluttered with gifts from fans, a mug reading “I’m A Surgeon, What Is YOUR Superpower?,” and an autographed Miami Heat basketball he won at a recent auction. “I’ve been through a few media circuses since then. It’s kind of fun. You never forget your first.”

He thought the book would be something he’d display in his office. “Not something Jezebel would blog about with 4,000 comments or that the Today show would call me and beg me to come to New York. It was unexpected, but it was kind of cool.”

In a clip of the doctor speaking to Kathie Lee and Hoda in 2008, he hardly seems cool. Sitting in Rockefeller Center, he confidently explains his logic behind the book (namely, helping kids understand what’s happening to their post-op parents), but slows when he’s hit with follow-up questions. Here, he seems less like a villain and more like a “very sweet man,” as Kathie Lee calls him. Consider his pedigree: a medical degree from the elite Washington University in St. Louis; a wedding announcement in the New York Times. His most salient point is that no one would think twice about straightening crooked teeth, so why is plastic surgery so different?

“At that stage in my life,” he tells me today, biting into a homemade cheese sandwich half-wrapped in aluminum foil, “my kids were smaller. I actually was more outwardly and inwardly religious at that time. But I did like the attention. I feel like that probably triggered something inside me that needed to become Dr. Miami.”

So he continued to pursue gimmicks, like the app he launched in 2009: iSurgeon allows users to upload photos of themselves or others and use a morphing tool to simulate plastic surgery. Like the book, it attracted headlines; the New York Times wrote that the app’s crude results were “worthy of a fun house mirror.” “Being a class clown, coming from that space, it's just funny to see people get all upset over something so silly. I never thought, I'm gonna retire off this app or this book.”

He trails off, trying to remember which happened when: free implants for an Ohio woman who panhandled with a sign reading “Not Homeless! Need Boobs”; “Operation Chuppah,” in which he offered free rhinoplasty to any Jew who needed it to find a mate; or his videos parodying Old Spice ads (which AdWeek excoriated in an article called “Is This the Worst Old Spice Parody Ad Ever? Dr. Schnoz Caught in a Nose Dive”) and Justin Bieber’s “Boyfriend,” with the lyrics tweaked to “If I was your surgeon / I’d never let you go / I could make your face / Look like it never did before” (which, when shared, could earn free Botox).

He can, however, remember the turning point: 2012’s “Jewcan Sam,” an original song and video that followed a Jewish man getting rhinoplasty to win over a shiksa. (The singer didn’t get the girl in the end, but did get a free nose job from the doctor.) “I wanted a viral video. I wanted to make a video that would get attention — but would also get people to stop thinking about plastic surgery as something that's bad, and something that's vain.” But the end result was more Blink-182 than Bill Nye. It included reference to getting “your nose circumcised,” lots of snapping cutting implements, and someone dressed in drag as Oprah.

The video did succeed in getting attention, including a barrage of headlines asking whether he’d “gone too far” and a televised beating from CBS’s The Doctors. It also drew the attention of the Anti-Defamation League and the American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Dr. Miami doesn’t seem flustered as he reflects on that time, sitting at the reception desk at the end of the workday. He says the Anti-Defamation League did its job — the organization has to be “hypersensitive” — but Jewish friends and papers defended him. And the investigation? “I think that the best thing that could happen for a viral video is to have ABC News call you and say, ‘What do you think of this investigation?’ I mean, I almost had to hold the phone away from my ear to laugh.”

So by the time he started Snapchatting, he wasn’t worried about legal or ethical pushback. Broadcasting plastic surgery is an established practice, from Extreme Makeover and Dr. 90210 in the early aughts to Botched today. “We've done a whole bunch of little shows, like MTV's True Life and TLC's I'm Addicted to Plastic Surgery,” he said, so he already had experience working with patients on camera, and had the paperwork in place to do so. “Very rarely have patients been like, ‘Oh my god, just take it off of Snapchat, I can't see this,’ and I'll just go, OK, fine. Delete, delete, delete, done.”

Other than that, he says, he hears almost no negative feedback. After all, the million-plus people who choose to watch him are a self-selecting bunch. The platform isn’t built for hate-watching, let alone substantive criticism; there isn’t even a comments section. That will surely change once he gets a TV show. Imagine the think pieces: kids and plastic surgery! Cultural appropriation! Medical ethics!

So why mess with a good thing? Does he worry that being exposed to a larger audience could turn the tide against him and make him America’s most hated doctor all over again? “I don't really worry about it, because I really don't care. I'm almost 44. I've got five kids. I've got a practice. I've got bigger fish to fry than somebody sitting at their computer and typing some nasty comments.”

The American Society of Plastic Surgeons declined to comment on Dr. Salzhauer’s practice specifically. “Regarding the broadcasting of a surgery,” a representative said, “there are so many variables to consider with each surgery location, procedure, patient, and doctor. Absolutely, privacy laws and patient consent that must be honored. Ultimately, any broadcast is at the discretion and consent of the facility, patient, and doctor.”

Then there’s his other code of ethics: his religion. He and his wife converted from conservative to Orthodox Judaism in their twenties, inspired by the life-and-death stakes of his profession. Yet his brand of button-pushing requires frequent violations of his faith. His daughter, for instance, has a problem with him hugging female fans, since touching women besides his wife is strictly banned. “She said, 'If you ask the rabbi, I bet he won't give you permission to do that,'” he says. “And she's probably right. So I don't ask the question.”

Then there are the rap lyrics he plays (and often sings along with), procedures like the O-Shot that are meant to improve women’s orgasms (which drives his wife crazy in the complete opposite sense of the word), and his willingness to appear in gossip mags. While showing off the gifts from fans that litter his desk, his phone buzzes with a message from an editor.

“‘Comment request for Radar," he reads from his phone. An actress "stepped out this week with a very peculiar looking face.’ Peculiar looking.” He points at the photo the editor included, and scratches his temple, thinking. “What do you think? It's hard for me to tell. She just looks a little older. What I look for is Botox. Everybody gets Botox. But I see lines there so....Let's see if she got her lips done.”

Plastic surgeons have long been the gum under the shoe of tabloid culture, trading their professional opinion to lend credibility to a story, and getting cash or exposure in return. I ask if he has any ethical concerns about speculating about people who aren’t his own clients.

“Look,” he says, “All plastic surgeons do it. … And with the exception of — who's that girl with the crazy dad? Lohan?”

“Michael Lohan called my office one time like, ‘How dare you talk about my daughter.’ But with the exception of that, I've never had any celebrity PR people ever say, ‘How dare you say she had Botox’ or something. Mainly because they probably had a lot more. So do I have ethical problems about talking about it? Not really. Some people might. I feel like they're out there and if you put enough caveats to it. And,” he says, touching on a topic he’s intimately familiar with, “some celebrities want their plastic surgery broadcast. Especially the reality stars.”

He seems so confident. And yet, later on, I ask whether his kids’ classmates ever gossip about their dad at school. He has an unusual job, after all — one involving body parts that make kids giggle. “Nah,” he replies, certain. “In Orthodox Judaism as we practice it, gossiping is a big no-no. A big no-no. So the kids, even though they’re not perfect, are taught not to gossip. If a teacher heard them say, 'Your father is na-na-na-na,' they’d go, ‘Are you gossiping?’”

But isn’t giving comment to tabloids about strangers’ surgeries gossip?

“That is a valid moral hypocrisy. On the other hand…” he takes a pause, the longest one since I arrived. “With the exception of Michael Lohan, I think it’s kind of part of their business, as celebrities. And I would bet that their publicists place those stories. It’s not like who’s sleeping with who in your neighborhood. But you’re right. My rabbi—” He trails off.

It seems like transitioning into real reality TV will only make it more difficult to keep in line. All these nice families go on reality TV, and their lives fall apart. The parents get divorced. The kids are messed up. Look at anyone on Bravo. Why would he want to expose his family to that potential destruction?

“Look,” he says. “I think that if I wasn’t an Orthodox Jew, I would probably be divorced and have two kids and be living like some kind of degenerate. We pray three times a day. I have to put on tefillin and there are certain ritualistic things you do every single day. It’s like how someone in AA goes to a meeting at least a couple times a week to remind themselves: If you go off the path, you’re in the gutter. So that is what I’m hoping will work. And I also know that it could all go away.”

A few weeks later, I’m trailing Dr. Miami as he barrels through the eighth annual Shorty Awards, the social media fete for which he’s been nominated for Snapchatter of the Year. The room is a who’s who of Whos, with YouTube stars and style bloggers and internet-famous dogs who seem practically sedated.

He’s pushing through the Times Square step-and-repeat line trailed by his new PR rep, Dom, a tuba of a man who says he previously worked for DMX. The guys have heard a rumor that DJ Khaled is in the building (he is! I see him!) and won’t rest until the doctor is face-to-face with the human meme. Dr. Miami has been desperate to collaborate with Khaled, but since the producer-cum-internet personality hasn’t returned his calls, he’s been busy working on a backdoor way in: collaborating with people in Khaled’s Snapchat universe.

The last day I was in Florida, Khaled friend and SwiftKick Sneaker Wipes entrepreneur Spencer LeGrande stopped by the doctor’s office. He was joined by KJ Anderson, Khaled’s regularly featured masseuse, and a fresh pair of black Yeezy Boost 350s, which he was gifting Dr. Miami in exchange for promoting his product. “What I'd like to do is have some kind of meeting with DJ Khaled at Finga Licking and have a whole thing at some point,” Dr. Miami told me. “And [Spencer’s] trying to arrange that.”

Yet tonight, there are no strings. No managers to contact or hoops to jump through. Just two fortysomething men in a sea of 12-year-olds.

The meetup is a success. Dr. Miami reaches up to hug Khaled and snaps a selfie, surrounded by a crowd of onlookers. And then...it’s over. They don’t exchange numbers, or talk shop about their brands. Dr. Miami is deeply satisfied, but the win seems hollow. His fans might be thrilled that they appeared in 10 seconds of footage together, but for now, it’s nothing more than that. A quickie. In an instant, Khaled is off to selfie with other social media stars.

But it doesn’t really matter. The doctor’s internet fame has secured him two years of bookings at his real gig, so he doesn’t need to win Khaled's affection, move to the Vine complex, or get in bed with sketchy teatoxes to pay the bills. Even a reality show would be a passion project. “Honestly,” he tells me, sincerely doing his best not to sound like a dick, “There's not that much money in TV for me. I'm a plastic surgeon. In Miami. So even $5,000, $10,000 an episode — I mean, if I were on Jersey Shore and I'm Mike ‘The Situation,’ that'd be like, ‘$10,000 an episode! How much beer I can buy!’ But that's like half a day's surgery, not even.”

So instead of worrying about turning a profit, he gets to pretend he’s a 16-year-old hip-hop-head and cultivate side projects “for fun” or “for attention.” Of all his spin-off businesses, he says only two have a chance of making real money: GoFox, a mobile Botox brigade currently operating in downtown Miami; and what his team calls a “social media incubator for medical practices,” in which plastic surgeons spend $15,000 for a two-week branding and social media training with him in Miami, and subsequently pay $2,500 a month to be shouted out on his social media accounts. (“It’s kind of like rappers. … We all have egos. We're all artists in our own way. But you can still have an alliance. I can bring them up on stage — like Jay Z bringing up somebody on stage and saying, 'Hey, he's my man.'”)

Dr. Miami doesn’t win a Shorty Award. He knew Khaled would take it; he’d spent the last few weeks preparing his family and staff for the loss. He and his family sit starry-eyed in the front row as the hosts announce a hodgepodge of winners including Kevin Hart, Khan Academy, and Pizza Rat. Hart sends in a prerecorded video acceptance speech, as does the winner of Best Vine Comedian, whose mom wouldn’t let him be here tonight because he’s still in high school and the SATs are this week.

The family wraps the night at a kosher pizza place by their hotel, and early the next morning, the doctor does spots on Power 105.1’s Breakfast Club and Z100's Elvis Duran and the Morning Show. On the radio, he’s a little bit lewd (Charlamagne Tha God really wants to know about vaginoplasty), but quick to correct any implication that he’s not professional — a criticism that will likely follow him as long as he’s goofing around in the operating room.

“They say the statistics are if you have 36,000 surgeries, someone's going to die,” he told me back in Miami. “Complications are going to happen whether you are a funny person, whether you're a serious person. You cannot control how things are gonna go afterwards. All I can do is make sure things look good in the operating room and that things are safe and good and I give them good care afterwards.”

In the Elvis Duran greenroom, he seems relaxed and awake, even at 7 a.m. He insists the producer not bother with “Salzhauer” — these days, everyone calls him Dr. Miami. He’s wearing his logo-adorned scrubs, which he also wore to the awards last night. A few Duran staffers take him into a back office for informal consultations. “There’s so much interest in what he does on Snapchat,” Duran tells me, explaining why they wanted him on the show. “He really is, in my opinion, the pioneer of bringing procedures out of the procedure room and out into the open for the world to see.”

With that, he’s off to see the wizard of ethically compromised doctors: Dr. Oz, where he will get criticized for "blurring that line between entertainment and surgery." It’s the first time he’s done a press blitz like this — does it feel like a practice round for what’s to come? “If it happens, it happens,” he says, tempering expectations. “How many 44-year-old guys get to do this?”

Walking through the skyscraper’s sweeping art deco lobby, he tells me about his Passover travel plans, and I ask whether he wouldn’t want to talk more about his faith on social media. “I do. I do. I do,” he says, looking out at the spring rain starting to fall. “It’s very touchy. People have very strong emotional attachments. Good and bad. And it’s kind of like the third rail in pop culture.”

Shooting out of the revolving door, he starts to walk for his car, then turns back around. “You’re right. I think about that, and it’s something I’d love to do in the future. But I have to figure out the right way.” His sister-in-law Rosy notes he does talk about it sometimes, like when a holiday is coming up. “I put it out there to some degree,” he agrees, “but I remember when we took the family trip to Israel. There was a lot of hate. A lot of anti-Semitic stuff came through. I certainly don’t want my family to be in danger or anything. So it’s tough to find the balance. But it’s something that I’d love to do.”

We say our goodbyes and he springs toward the waiting SUV, ready for Oz. Then he’ll fly back to Miami. He has surgery tomorrow morning, which is still his primary occupation, though he continually points out that, too, could disappear any time — whether for a touchy ethics board, that statistical patient dying on the operating table, or just a change in luck.

A moment passes and Salzhauer jumps back out of the SUV. He got in the wrong car. •

UPDATE

This story has been updated to clarify the location of Dr. Miami's office.