“Without light I am not only invisible, but formless as well; and to be unaware of one’s form is to live a death.”

—Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

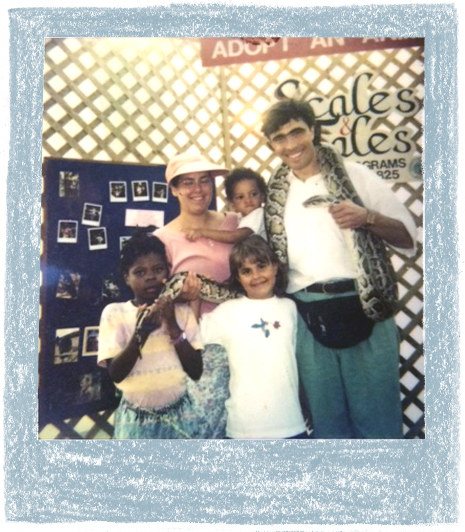

Let’s begin with the picture. A small Polaroid taken of my family in the early '90s at a flea market in Denver, Colorado. There were five of us then. My mother, father, baby brother Devan, little sister Eva, and me, Mariama, the oldest. We are standing in front of a booth that reads: "Adopt an Animal: Scales and Tales." My father has a boa constrictor wrapped around his neck, and we all crowd in around him. Eva smiles like a diva under the crook of his right arm; my mother, in her faded pink sun hat, holds Devan in one arm and the tail of the snake in the other, and I am on the outside holding the very tip of the snake’s tail, looking petrified. The portrait is at first hilarious, capturing our family dynamics to a T. It is an all-American family portrait except for one detail: My parents and Eva share the same white skin, while Devan sports a head of curly hair and a peanut-buttery skin tone, and I, a bundle of locs on top my head, wear a complexion the color of wet bark. This is my adoptive family, my kin. A loud, passionate, stubborn mixture of people who don’t look anything alike.

For the last decade, this photo has found a place on my fridge. Nestled between a collage of menus, drawings, and Frida Kahlo magnets, it has traveled with me to grad school in California, to a new job in New York, and now to Michigan, where I live with my wife. At first, I tacked it on the fridge in a place of prominence, willing myself to acknowledge its innocence, its obvious nostalgia. In my twenties I wanted so badly to be proud and sure of my rainbow upbringing. To believe that our differences did not divide us, but made us stronger, happier. I was still trying to live up to my parents' assertion that in their house “color didn’t matter,” I was just “their baby” and they loved me as their own. And I don’t doubt their love. There is love in this story. But there is also silence and pain around one blaring truth: We are different. My black skin is proof.

What’s more American than keeping silent and smiling for a camera? Now, in my thirties, I see this picture on my fridge and I am filled with a smattering of emotions. Who is this little girl covered in shadows? Scared and uncommitted, my body arches slightly away from the rest of my family, my eyes full of fear, unsure of where to look. I know that it is natural to question one’s roots. To hold one's gaze in the mirror and study what kind of person you’ve become. Am I the daughter my parents raised me to be? Do I carry my mother’s purpose in my walk? Do I speak with the cadence of my father? But along with these questions come others. Whose eyes do I have? What silences have I been holding on to? Will people accept me, unconditionally? Who am I?

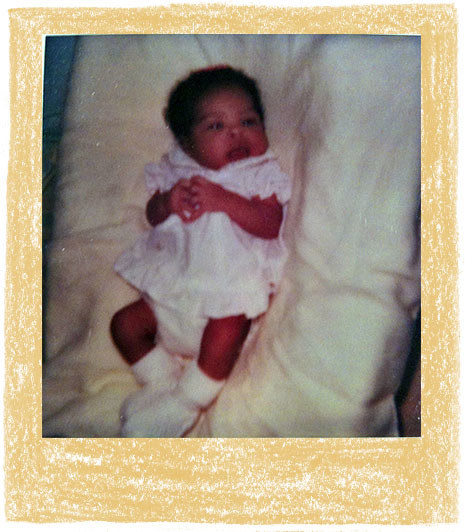

I was three weeks old when I was adopted. I arrived in Colorado, from Georgia, wearing a Santa onesie and was handed off by a social worker to my bright-eyed white parents like an Olympic torch of honor. It was the early ’80s, and adopting black kids wasn’t trendy yet. There were no Brangelinas or Madonnas sporting their multiracial families all over the tabloids, and there was certainly no Barack Obama helping broaden America’s concept of family. When my parents tell me about the happiness they felt the day I arrived, or how cute it was to watch me play with the hose in the garden as a toddler, I am always filled with a sense of dull grief. These are supposed to be the happy stories. The ones where we are just like any other family, going to the park, eating dinner together, picking out a new puppy from the pound. These are the stories where we pile into bed together on a Sunday, when my father makes buckwheat pancakes, and my mother buys us girls new polka-dot dresses to match. These are the stories that are supposed to keep me grounded. But these stories are tangled with other rememberings, memories of another mother with no face and no name, whose body was my first home. There is always a desire to be whole, to have the same nose as my father or the same annoying allergies as my mother. Who do I look like? I used to whisper to myself, pinching my fat cheeks in the mirror. I hear these stories and I look at this picture and still feel unseen.

It was the early ’80s, and adopting black kids wasn’t trendy yet.

It wasn’t until I was in college, when I really started looking for literature about being adopted by white parents, that I realized how undocumented this experience is. Googling "transracial adoptee" only brings up a few anthologies and memoirs, a handful of legal documents and books written about the process of adoption. Where were the black girls like me whose white parents knew to rub lotion on their daughters’ dry skin but didn’t know to sit them down and tell them what to do when a cop pulls them over? Where were the black girls like me who held their grief on their shoulders and feared losing everything if they spoke up? What did their American snapshots look like?

I am 3 years old and the sandbox is a deserted island. I know that I am different, but do not have the words to understand how. I know that riding on my mother’s back in the grocery store turns heads and sparks comments at the checkout line. I know that I am loved. That when the sun goes down I will eat rice and tempeh burgers for dinner, that Luchea, our bullmastiff, will guard my bedroom door as I fall asleep to the sound of my mother’s violin coming from the den. At the park I make friends and invite them onto my island. We teeter around, guarding our territory and renaming ourselves after queens. My mother calls and I ignore her, convinced she is a dream. My father calls, louder now, and I run to hide behind a tree. I do not want to leave. I am 3 years old and my mother is pulling me now towards home. I kick and scream in protest, throw my hands in her face and squirm from her grip. And then there are more voices. Tall figures surround us and demand an explanation. “What are you doing with that black child?” someone yells. “Where are you taking her?” I do not see my parents' faces, but I feel my mother’s grip tighten. “ She’s our daughter,” she says, “and we are taking her home.”

I am 5. My little sister Eva sports a head of white-blonde hair, and at night I wear towels on my head, pretend I am Rapunzel with the wind blowing gracefully through my long locks. What I know is that after too many miscarriages and my adoption, Eva is my parents' miracle child. I am slow to accept her. When she is a baby and my mother nurses her, I sneak quietly into the room and kick my mother’s shins, before running away. When Eva naps on her sheepskin in the living room, I find ways to “accidentally” step on her head. What I learn is that there are small battles I can win. We go to the beach and I flaunt my brown body as Eva sits under the umbrella waiting for multiple layers of sunblock to dry. We play barbershop in the attic and I hack off her lovely locks so that she looks like a young cancer patient for months afterward. My mother sends me to my room and I tell her I want my real mom, the one who looks like me. What I know is that I do not have my mother’s eyes, even when the lady at the mall tells me I do. I know that my hair is curly and thick, that my mother wants me to love it natural. I know that when she drops me off at Jasmine’s to get my hair braided I feel safe. That even though it hurts when she untangles my kinks I don’t mind because she smells so good. I learn that I love the smell of black women. Of grease, flat irons, and cocoa butter. I know I am black and that my parents love me, but I know I am different.

I am 10. We move to Albuquerque, New Mexico, and I start the fifth grade. We live at the end of a dirt road, on a half acre of land, and I learn that my bike is freedom. Each morning I ride to school alone, so that I don’t have to deal with questions like “Who's that white lady dropping you off?” or “ THAT’S your sister?” or “What happened to your real mom?” Even some of my teachers can’t help asking where my real mom is, and sometimes I say: “She’s dead.” Just to shut them up, even though I have no idea. I want to be liked, and so I try, for a couple of weeks, to “mean girl” my way into existence. I stop reading books at recess and start walking around the playground with a group of girls in my grade who give me a list of gifts to bring them each day in exchange for their friendship. I bring them stuffed animals, candy I steal from the store. I give them secrets, I tell them about my crush, on Eric, the redhead in our class. “Oh,” Sheena says, giggling, “he doesn't date black girls,” and then I laugh along with them to keep from crying. I give them big, hurting smiles. I know that I am smart. Brave. That one day I will live in a big city, in my own apartment, overlooking a park, but for now I am silent. And when, one day, playing dodgeball, I make a home run and slide into the home base Sheena is protecting, she leans down and whispers in my ear: “Whatever, this point barely matters. Black meat attracts flies, you just remember that.” And again, I am silent. I bike home after school and sneak into my room. I close all the curtains and crawl into my bed. My mother comes in. “What’s wrong, booba love?” she asks at the doorway. And I don’t tell her, because I know she won’t know what to say. Or because I think I am protecting her. Or because I am afraid she won’t believe me. Or because it hurts too much to acknowledge the ways we are not the same. Or because I am ashamed of being ashamed of my skin. Instead, I yell at her to get out of my room. For everyone to just leave me the hell alone. Or maybe she never even comes to my room at all.

I am 16 and waiting at Penn Station to visit my friend Leah in Baltimore. My father has come to see me off. We sit at Dunkin' Donuts, drinking sugary coffee. He pats my hand and tells me he’s so proud of the young woman I am becoming. Out of the corner of my eye I see a woman. She has on two different shoes and carries a canvas bag filled with plastic bags. Her skin is the color of milk. She paces around the front of the café, muttering under her breath. She is looking at me, at his hand on mine, and muttering under her breath. My father leaves to throw his trash away and use the bathroom. I bury my head in my backpack, searching for what? Nothing. The woman is speaking to me now. “Whore,” she says, “what are you doing with that white man? Shame on you.” I do not move. I watch the clock on the wall until the numbers change, and bite my bottom lip until it bleeds. I want to tell her she is wrong but everyone is watching. When he hugs me goodbye on the platform, I still feel her eyes and I pull away quickly. I do not tell him a word of what has passed. I want to hide my budding breasts and throw a hood over my head. I don’t belong to him like that, I want to tell her.

At 24 years old, I stand on the Fruitvale BART platform where Oscar Grant was shot just two months before and say goodbye to my father as he boards a train to the airport. I am a teacher now, and this place, Oakland, has become a home too. We do not speak about Oscar his whole visit. In fact, we do not speak of black bodies being killed, erased, or hunted much at all. We’ve never been able to talk about this. I’ve learned to pick my battles or to not enter them at all. I am heavy at the thought of what we cannot say. I’m so heavy I cannot wait for him to leave. To be free of his whiteout of an embrace. How can a father hold me and erase me all at once? It is February and Obama has been the President for less than a month and I am wondering what these black men standing beside us are thinking of me as I hug my white father in the place where Oscar’s blood fell. Maybe I am being paranoid. The Bay Area is more evolved than most places; they must know I am his daughter. That he has spent the day scolding me for running up my credit card bill and taking shit from my boss at work. He is my father and he worries, I want to tell them as he steps onto his train and waves at me through the window. You are my father and I’m worried you don’t see how easily I could have been on that train, with Oscar, I want to scream at him. Instead, I watch the train speed away.

I am 29. I sit at my parents' dinner table for my brother's birthday listening to my mother joke about the “hard to pronounce” names of her black music students. “ I can’t keep them all straight,” she says, laughing. I am shaking in my seat. “Well,” I clap back, “it’s better than a bunch of Tiffanys, Katies, Jennifers, and Beckys.” The table giggles awkwardly, and then it’s back to cutting the cake. I see a flash of something in my mother's face. Shame, recognition, accountability, anger? What? But we move on. I pour myself a fourth/fifth/sixth glass of wine and gulp it down. My shoulders hike up and my neck aches. I let out a deep sigh, and then glance around nervously to see if anyone has heard it. Recognized it. I feel small. I flash back to being little. To developing insomnia and anxiety so bad, I would pinch my thighs obsessively to stay awake. To my mother always telling me to stop being so serious, to “relax my shoulders,” to stop reading the dictionary at family parties and just “have fun.” And my sighing. How it has always bothered her. How when I’m in my parents’ house and trying to survive, I retreat into myself, turtle up and hold my tongue. How sometimes the only way I know how to release, how to be heard, is with my breath. With one long, low, tired sigh filled with so much anger, it almost chokes me.

It’s August 2015. I drive across the country with my partner, and I am hyperaware of our black woman bodies against the Midwestern landscape. We are one and a half months married, two and a half years in love, and all of our wealth (mostly in boxes of books and diplomas) will meet us in Michigan via semi truck. This is the American dream: a young couple with a caravan of belongings, headed to their first two-bedroom house in an affordable city, on a small plot of land, with a porch and a garden and room to grow into. This is the kind of life that screams: "BOOTSTRAPS, we’ve pulled them up and here we are, alive."

“I will light you up!”

The words of the police officer who arrested Sandra Bland just weeks before reverberate in my head like cannon fire. We hear the siren at the same time. Our bodies stiffen and we stare out the windows, searching for the source. We turn down the music. We are in the Wilds of Pennsylvania, and even though it is green and lush, every tree, every roadside gully is a reminder of where our story might end. The siren screams past and fades. This time, it is not for us. We let our breaths turn even. “I love you,” my partner says, smiling in the driver’s seat as she turns up the music and takes another sip of her coffee. I am slow to relax; I attempt to loosen my shoulders and try to focus on what’s ahead. And when my father calls, somewhere in Ohio, I tell him we are fine. “No roadblocks, or stress at all.” And the lie is so easy, it stings.

Let’s go back to the original picture. I am a mess of ashy elbows and crooked teeth. I know I am loved, but I feel like everybody at the flea market is looking at me. I am terrified of snakes but even more terrified of being left out. I squeeze in at the last moment, determined to belong and for everyone to know it. The camera snaps. The photographer holds out the picture as it reveals itself. We all lean in to look, and laugh at the outlines of our forming shapes. But when it develops, my face is twisted with worry.

A few months ago, in therapy, I found myself uttering the following words: "But if I’m not a good girl, who will want to keep me?" I am 31 years old and I still feel as though I owe this picture, my white parents, something impossible: my silent gratitude. I still feel that if I dare to question, challenge, or speak truth to my snapshots as a black transracial adoptee, I will be “sent back” or “unadopted” for being ungrateful. What happens if I say to them:

Look, I have often felt unseen in your home, your home in which I was in many ways expected to live up to the myth of colorblindness. Your love alone does not protect me from the fact of my black skin.

This June, 49 queer people were murdered in Florida on my one-year wedding anniversary to my wife. I didn’t hear from you. Then we lost Alton. And then Philando. And yesterday was the one-year anniversary of Sandra Bland’s murder. And you are silent.

I have learned to accept this silence. I protect you. I protect myself. I make excuses for our family. We are creative, talented, passionate, but we don’t talk about our differences. I have played the grateful bastard really well, believed it was my job to hold all of this sadness, this violence, to get by in this skin on my own. But it’s not enough. Where are you? Maybe you think I am an exception. I am not. Maybe you think your silence is better than fumbling awkwardly through uncomfortable realities. It’s not. I am a black, queer woman in America, I am your daughter, and I am always in danger. Or maybe, like many white people, you just feel overwhelmed by it all, and so you opt out of addressing oppression or injustice all together. You think: This is too hard. You leave it at that.

You erase me in doing so.

I need you to know that.

Mariama J. Lockington is a writer, educator, and transracial adoptee who calls many places home. She is a Voices of Our Nation Arts Alumni, a Literary Death Match Champion, and the founder of the womanist project the Black Unicorn Book Club. Mariama is published in a number of journals including Prelude Magazine, Washington Square Review: Issue 36, Read America (s) Anthology (Locked Horn Press), and Bozalta Journal. You can find more of her work here.