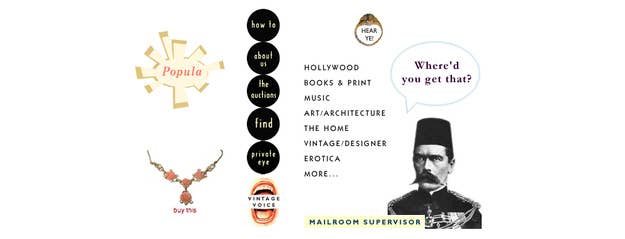

At the turn of the century I spent about a year raising money from VCs for a dot-com company I'd co-founded. Popula was like a mini-eBay, but for vintage and rare goods, and for rare books. In early 2001, after four years building the business, we finally managed to wrestle down a term sheet from a small venture firm for $8 million. Alas (or maybe not, as we shall see), the crash of April 2001 arrived before the money did. But during that year, I learned a lot about VCs and how they think.

The memories of that period will forever boggle. The darting eyes of hundreds or thousands of hungry/crazy opportunists. The horror of hearing the phrase "monetizing eyeballs" for the first time, and the well-nigh uncontrollable desire to leap across the table and plunge my fork into the speaker's chest. Taking a seat in the opulent offices of a "Biz Dev" VP at a dot-com entertainment company funded to the tune of $60 million, and finding myself across from a squirt so young that I couldn't help blurting out, "Um, can I talk to your dad?" Seizure-inducingly horrible, ostentatiously expensive furniture and artwork by the truckload, a never-ending cascade of floor-to-ceiling glass walls, a blur of huge, self-important conference tables.

Also: the thrill of watching our beloved project come to life. The shared pleasure and excitement of colleagues, programmers and customers, experiencing this extraordinary moment together. Knowing that you were watching the birth of a medium that was about to change the world. That you were part of it.

We learned that they liked to be taken to lunch at the movie studios, the VCs, because that is one of the few places you can't just buy your way in. They could be a lot of fun, loved to party, loved good food, good wine. Also, loved Ayn Rand (both Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead) but no other novels at all. They said the most unbelievable things. "We won't look at a company without a potential market of at least $100 billion." "We're not looking at profits, we're looking at revenues."

To be fair, the development side was just as surreal. One afternoon I found myself in the galley of this podgy network guy's boat, this bizarre guy who ran a gang of Oracle geniuses, when suddenly he emerged from the cabin in his underwear. In Florida, a network security specialist met me while brandishing a lightsaber of his own design. He turned out to be totally useless: Our servers were decimated by a virus that was nothing by today's standards, a tiny little bug that anyone could clear up in five minutes on his own nowadays.

So why even invest all this time and effort in trying to raise outside money? In those days eBay, our principal competitor, did not dominate to the extent it does now. We'd put a lot of our own money in, hundreds of thousands by the end, but that was no match for the avalanche of money being spent by eBay and their top-tier competitors, Amazon and Yahoo, both of which had launched competing auction sites in an attempt to wrestle that explosively-growing business away from eBay. In order for us to establish a permanent foothold, even to make ourselves heard above the din of our half-dozen or so competitors in the second tier — most of whom were venture funded — it would be necessary to spend at comparable levels on development, advertising and marketing.

So: Pitching, pitching, pitching. Lots of airplanes, lots of talking. There was a truly scarring event put on by the Forum for Women Entrepreneurs, at which it was suddenly announced that the first five to reach the podium would get to pitch. A physical race between women in business gear. Those in heels were courting trouble. Many were like myself, transfixed with fifty kinds of horror and dread and rooted to the spot.

Finally, we signed a deal. Champagne all around.

One of our VCs arrived at our ramshackle Hollywood Boulevard warehouse offices in a huge white stretch limousine. "Jesus who have you got in there, Van Halen?" I exclaimed, injudiciously. We showed her inside.

"Wow," she said as she examined the musty, book-stuffed interior. We trembled inwardly. "Some of our companies have paid, like, hundreds of thousands of dollars to look like this."

It had seemed like heaven, that $8 million term sheet, in exchange for a quite reasonable hunk of our company. Enough for our programmers to revamp our product with every feature we (and our customers) had dreamed about, enough to mount a complete guerrilla marketing and ad campaign, enough to hire everyone we needed, enough to — hang on a minute — enough to pay a bunch of consultants about $200,000 (consultants that our investors had also invested in via a portfolio company), our new partners suddenly informed us. Enough, also, to pay the interim CTO these consultants had chosen for us $40,000. Per month. "You should be thrilled to have this guy for a CTO," one of them insisted.

Quite commonly VCs will fund a startup and then they will commence to spend the money themselves at a furious rate. That way you will need more and more, and be forever beholden as your equity melts down to nothing. Very few startups have made it through that gantlet unscathed. In an ideal startup, every bit of equity would stay in ironclad hands. (Even Craig Newmark, one of the smartest and best Internet entrepreneurs in history, ran into trouble when a partner insisted on selling out his stake to the dreaded eBay, resulting in a poisonous relationship that is still being litigated to this day.)

Very soon after the deal closed, we were told to meet with the top dog at another of our VCs' portfolio companies. They had this Java-based method of creating storefronts. I test-drove their clumsy, bug-ridden, terrible-results-producing monstrosity of a product. These programmers had no earthly idea how to design a consumer interface. Most of their applets spawned those little grey boxes, the ones you had to give all these permissions to, constantly. So we obediently had a meeting with their CEO. Which was a catastrophe.

"Look, this is very simple," I explained to him. "There are three elements in this game. A chick, a wallet and a Visa card. You have to get the chick to remove the Visa card from the wallet in order to win. And if she leaves the site because she is confused by your little grey boxes —"

How pityingly he looked at me. "Well you have to understand, Maria —"

"Actually no, I don't. My customer won't, so I don't have to. She's the one we need to be worrying about."

Mr. Head VC phoned me up and gave me a rocket about how they'd only invested in Popula on account of the Synergy with Java Boy. "Well you know, S., their thing does not work, is the problem," I explained, over the sound of my grinding molars. At our last meeting, we sat around their over-designed conference table in a chilly near-silence. It emerged that Java Boy and his troupe of clowns had their own ideas about how our product ought to be built, complete with inane acronyms. We proposed a few compromises, based on what we had learned from actual paying human beings, and were summarily shot down. We were small potatoes, and we were expected to do what we were told.

We were weighing our options when the crash came, and blew the deal off the table.

So here is the question: what are the ultimate goals of investment in our tech future? Are they being served by those currently in charge of that future?

I did meet one angel back in those days, a very rich entrepreneur, who articulated something of the problem we were facing then, and are now facing for the second time.

"If you're doing this mainly so you can get rich," he said, "that's a huge red flag for me. The people who are going to succeed aren't the ones who just want to get rich."

An especially striking remark, because this guy's own impulse was manifestly, obviously, to get rich(er) and yet he framed the question of whether or not to invest in other terms entirely.

Those in the investment community often pay lip service to the romantic idea of themselves as "innovators" and "creators" and what have you, but aside from the mere self-congratulation, there are a few who understand that even if you are inclined to equate "success" and "wealth," you'll need more than just greed in order to get there. The billionaire angel investor Ron Conway demonstrated this reasoning in an email to his colleagues leaked during the Angelgate scandal of 2010:

The world of startups would be a better place if you spent less time complaining about deal structures, terms, vc’s, and valuations etc and the cars you drive, and just helped entrepenuers [sic] build their companies. [...] In my opinion your motives are driven by self serving factors around ego satisfaction and 'making a buck.

And yet this famous VC-chiding email has nothing explicit to say about creating value for the society at large; it is all about helping entrepreneurs build companies.

In the twenty-odd years of its existence, the Web has become the province of virtual monopolies (and the U.S. has become stuck at over 8 percent unemployment) for this exact reason: the inability of those in charge to realize the interconnectedness of the culture. Particularly, the false conviction among the rich that the middle class needs them more than they need the middle class, culminating, perhaps, in the ravings of Edward Conard and his cockamamie trickle-down-on-steroids theories.

So long as we continue to measure "success" — and allocate cultural and political influence — in dollars, we will remain at the mercy of those suffering the curse of Midas — the special gift of paralyzing all they touch through their thirst for gold.

The direction of technological innovation is determined by a very few great forces. One is the so-called "investor class" of angels and venture capitalists; another, the R&D departments of big technology companies. Government agencies like NASA and CERN and DARPA (the latter of which really did invent the internet) have their role — one in which the influence of industry has grown significantly. And then there are the universities. The familiar spectacle of cash-strapped administrators knuckling under to business interests reveals an increasing threat to the independence of the academy.

Because technology plays such a huge part in our lives, we might think a little more carefully about how our course is being set by a small number of narrowly self-interested parties. Is the future being planned in a way that benefits our society, our culture and our economy? Or are those responsible mostly mindful of the chance of a solid-gold exit strategy?