In 2013, while promoting August: Osage County, Josh Horowitz, an MTV News reporter asked Julia Roberts how she felt about Jennifer Lawrence’s induction into the “elite group of America’s sweethearts.”

“How many are there of us?” she responded. These titles, after all, are so seldom chosen by those who bear them. Besides, she explained, “My card is expired, and I didn't get a new one.” In any case, Roberts wondered, wasn’t Lawrence too cool to be America’s sweetheart?

Horowitz: She’s edgy.

Roberts: Isn’t she?

Horowitz: You’re edgy.

Roberts: Well. [beat] Let’s not get personal.

That exchange is a perfect example of how the Erin Brockovich actor has long both embodied and challenged her title. After all, to call Julia Roberts “America’s sweetheart” in 2018 feels both obvious and outdated. The label has always been an ill-fitting match, one given to her by the media. In recent years, Roberts, who’ll be seen on screens both big and small this fall (in Amazon’s thriller series Homecoming out today and December's family drama Ben Is Back), may have finally found a way to shed that cloying description by embracing a pricklier persona.

Her wit has become more cutting — one need only see her clapbacks on Instagram to see this in action. And her more recent late-night show appearances and interviews on red carpets, have been more frank and even edgy. She’s played (and lost) a curse-off against her onetime onscreen mom Sally Field on Jimmy Kimmel Live, all but peed her pants laughing while describing to Ellen DeGeneres how she loves scaring her own kids, opted to confront the dog that’s terrified of her face on The Tonight Show, and cursed on live TV while fundraising for Hillary Clinton ahead of the 2016 presidential election.

The carefree attitude that made her so relatable in her twenties has matured into a relaxed posture that’s kept her down-to-earth. Her charm, in turn, has sharpened, in a string of anger-filled performances starting with 2004’s Closer; there’s a severity to her recent onscreen roles that’s tinged her sweetness with some welcome bitterness.

Roberts’s ascent to American sweetheart status happened quickly. The Georgia-bred actor got her first major starring role as Daisy in 1988’s Mystic Pizza. Roger Ebert, who praised Roberts as a “major beauty with a fierce energy” was right to predict that the coming-of-age film may “someday become known for the movie stars it showcased back before they became stars.” Audiences got to see her next as Shelby the following year in Steel Magnolias. Playing up her Southern drawl, Roberts anchored the film’s tear-jerking drama with her sunniness as Shelby, the doted-on daughter of M'Lynn (Sally Field) struggling with Type 1 diabetes. She even earned her first Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress as a result. Yet it was the movie she was still shooting while attending that 1990 Academy Awards ceremony that would cement Roberts as a Hollywood superstar, Pretty Woman.

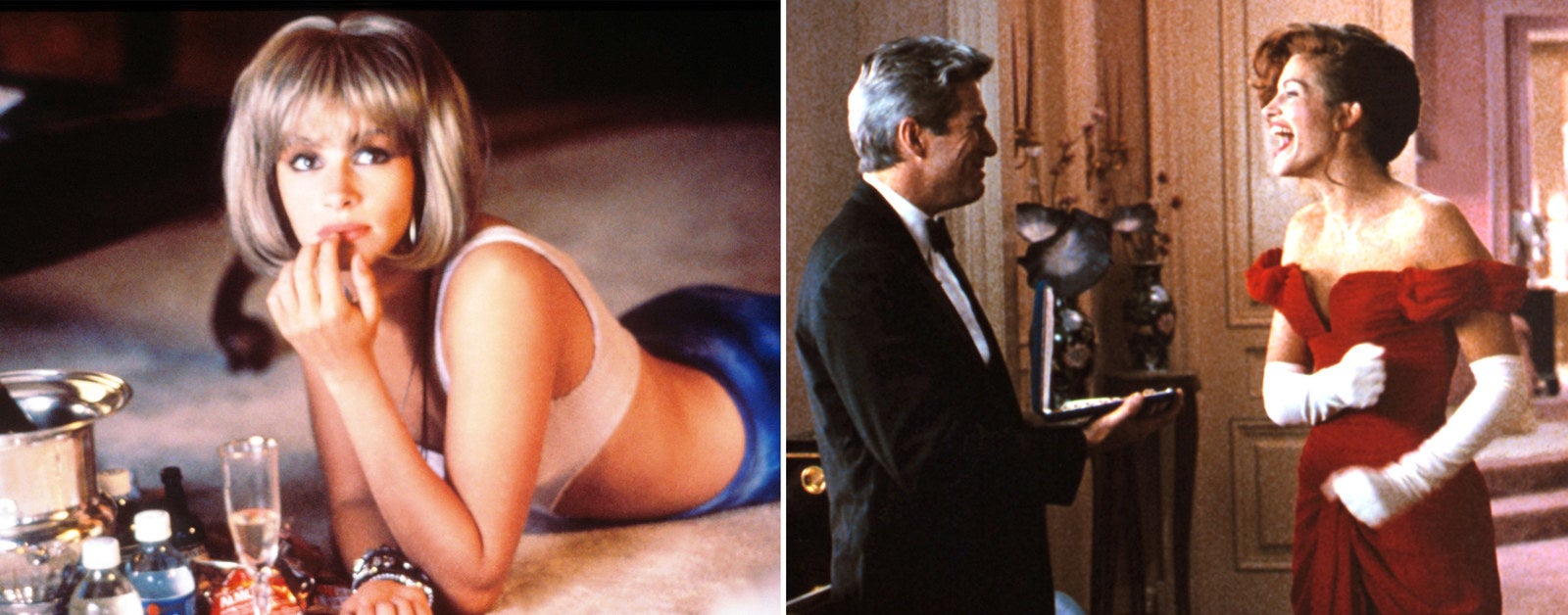

That Garry Marshall romantic comedy, a modern-day fairy tale about a “hooker with a heart of gold,” was a film that demanded a relentlessly charming female lead. To gloss over the film’s controversial plot Roberts needed to be convincing enough as a quick-witted sex worker with an edge, all the while suggesting a tenderness that would and did endear her to Richard Gere’s Edward and audiences alike. Giving moviegoers plenty of famous line readings (“Big mistake! Huge!”), Roberts made Vivian, whether wearing the now-iconic, gorgeous red evening gown or that blonde bob/miniskirt outfit she starts out with, at once a laughable goofball and a sultry romantic lead — no small feat. This is why the romantic comedy was so well-suited to her talents. When she throws her head back and laughs uncontrollably at I Love Lucy reruns in Pretty Woman, you can’t help but fall for her the way Gere’s Edward does. Compared to her contemporaries (say, winsomely brooding Winona Ryder or regal Nicole Kidman), she was, or at the very least appeared, genuine.

But early on, the need to pinpoint Julia’s allure often led to unsurprisingly sexist conversations about both her talent and her looks. Here’s how her first Vogue profile in 1990 opens: “The truth is, when you sit and watch Julia Roberts bring an iced cappuccino to those famous lips, her mouth isn’t all that big.” Writing in 1993 for Vanity Fair, Kevin Sessums went further, talking about Julia’s Audrey Hepburn–like appeal, that “once-upon-a-timeless quality of remaining magically innocent while prickling our most prurient interests. By turns childlike and sophisticated,” he went on to explain, “Roberts is the kind of woman one longs to tuck in — late, late at night. There’s a fairy-tale quality to her bedtime appeal.” This is the promise of anyone’s (but especially America’s) sweetheart: She’s ethereal and grounded, youthful yet wise, chaste but sexy. She’s not yet quite what she’ll become in the 21st century (Amy Dunne’s self-described “cool girl”), but she’s skirting that all-too-obvious male fantasy.

To try to trace when Roberts went from being a buzzy unknown to an A-lister begrudgingly carrying that sweetheart crown is near impossible. By the time Entertainment Weekly was (negatively) reviewing her foray into thriller territory, Sleeping With the Enemy, in 1991, the argument that “the movie plays off Roberts’ status as America’s sweetheart” proved how quickly the label had stuck. “America’s sweetheart” would soon replace “Pretty Woman” as the tag that would follow the actor around for the next 28 years. As Owen Gleiberman suggested in that review, audiences rooted for Roberts’s character precisely because she was so likable. Daisy, Shelby, and Vivian became the templates for the performances that would cement her as the most bankable actress of the ’90s. She was the gal every guy wanted to date and the woman every girl wanted to be.

Photo shoots from that period framed her as relatable and authentic. In that same 1993 Vanity Fair feature story, Roberts sits on the grass outside, laughing as she wears a frilly dress paired with boots — the epitome of a carefree princess.

Roberts may have been already past her teenage years, but the “sweetheart” label served to underscore her youth, calling forth a near-century of cultural connotations of the word. In her book American Sweethearts: Teenage Girls in Twentieth-Century Popular Culture, professor of gender and women’s studies Ilana Nash fleshes out these various ideas about how popular culture shaped this impossible ideal. In postwar-era films, she argues, the teenage girl became a fascination that helped to bolster a sexist ideology where young girls were both a fantasy and a threat. As she writes, the teenage girl was stuck in between girlhood and womanhood, burdened by the worst of both worlds: “Femininity makes her more sexually objectified than teen boys in the same narratives, while her youth makes her more ignorant and diminished than grown women.” The title, as those who bore it before and after suggest, carries with it an infantilizing connotation. From Shirley Temple and Doris Day to Sally Field and Meg Ryan, “America’s sweethearts” have always been young women who demand we care for them, in both senses of the word.

And if Roberts’s roles were decidedly grown-up, she still maintained a childish air about her. When she visited the Late Show With David Letterman in 1994 (already aged 26), the late-night host wasn’t wrong in pointing out she looked more like a girl than a movie star. With her shoulder-length hair down, nary a trace of makeup, and wearing a simple black dress with white socks and black shoes, she looked like an overgrown schoolgirl. That she then went on to regale Letterman with an anecdote about how she told her Mary Reilly director, Stephen Frears, that she would scream unless he told her his birthday (which she did when he first refused) only further underscored why that playful spirit fit the teen sweetheart label to a T.

And while her childlike charisma was likely what nabbed her the role of Tinkerbell in Steven Spielberg’s ill-fated 1991 film Hook, she mostly excelled in films that asked audiences to fall in love with her, as her leading men often did. So infamous were these affairs that they became the main way the tabloids covered her, knowing readers were eager to know who the actor was dating at any given time.

For every glossy cover that played up her girl-next-door image — say, GQ (in just a men’s shirt) or Rolling Stone (in a tank top and denim jacket) — there were just as many tabloid headlines that reduced her to a mere girlfriend. In fact, one can track Roberts’s many Hollywood affairs in People magazine covers: “Julia in Love,” as she began dating Kiefer Sutherland in 1991; “The Big Breakup!” when she left him soon before they were to be married later that year; “Julia’s Wedding Album!” following her nuptials to Lyle Lovett in 1993; “Bye Bye, Lovett,” after they divorced in 1995; “Julia & Her Law Man,” when she met Benjamin Bratt in 1999, and so on and so forth. Her tumultuous romantic life was often used as a cudgel to break down her “sweetheart” image. The salacious gossip about her only intensified the more well-known she became. (To judge by the National Enquirer headlines about her recurrent, ever-looming divorce, that hasn’t changed in recent years.)

The “America’s sweetheart” title, as it turns out, comes with its own dangers. It’s a pedestal that demands to be broken down; a target more than a halo. Decades before Jennifer Lawrence had to fend off hackers and slut-shamers alike, Roberts learned firsthand the way she could never live up to the image of her that the press had created. “Before I even walk in the door, I believe a lot of [reporters] have their thesis,” she told Vanity Fair in 1999 (and then, almost word for word, W magazine in 2002). “They have their little title, and there’s very little I can do to conform to something that I don’t know exists.” Paparazzi followed her everywhere she went. Tabloids tracked her roller-coaster romantic life. It’s no surprise that by the time she starred as a heartbroken movie star overwhelmed with her fame in Notting Hill in 1999, everyone assumed she was playing an exaggerated version of herself.

That London-set film has since become a classic and proved that the actor could still make us clamor for the boy (in this case Hugh Grant) to just shut up and kiss her already. But nothing could prepare audiences for what Roberts did with the titular role in Steven Soderbergh’s Erin Brockovich. The 2000 film told the story of the real-life Brockovich, a single mother of three who had spearheaded a multimillion-dollar lawsuit against an energy corporation. The role made perfect use of Roberts’s appeal. “Just as the eponymous heroine flaunts her body to win over the men whose help she needs, Erin Brockovich uses Roberts as eye candy for boyfriends and husbands,” Amy Taubin argued in the Village Voice. “She’s not a cocktease; there’s never a suggestion that she’s going to put out.”

Ryan Murphy, who’s directed Roberts twice — once in the feature film Eat Pray Love and later in the HBO adaptation of Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart — admitted back in 2013 that his favorite thing about Roberts’s considerable talent was when she channels her badass Erin Brockovich anger. “No one — and I mean no one,” he wrote in a Marie Claire profile, “is better at conveying moral outrage and advocacy than Roberts. Her temples throb, the veins pop, she is entirely and stunningly alive.” The reason Erin Brockovich felt like both a revelation of Roberts’s talent as well as the culmination of her onscreen charisma was because her character’s anger (“That’s all you got, lady. Two wrong feet in fucking ugly shoes.”) and charm (“They’re called boobs, Ed.”) showed the actor’s many gifts.

Following her Oscar win in 2001 (which she celebrated with a long-winded, cackle-filled speech, admitting she might never be up there ever again), Roberts’s career cooled a bit. Both films she released that year (The Mexican, America’s Sweethearts) underperformed by Julia standards. And then, after she married Danny Moder in 2002, her career took a backseat. As she explained in the most recent episode of Oprah’s SuperSoul Conversations, meeting her husband led her to reassess her life. “You realize you thought you were so clear about the compass of your life,” she told Oprah. “And then you realize, ‘Oh, there's more depth, there are other things here.’” When she was pregnant with her twins, Finn and Hazel, in 2004, she further retreated from high-profile projects, opting to focus full time on her budding family. The films she released that year, which included the Mike Nichols’ ensemble drama Closer and the Soderbergh sequel Ocean’s Twelve had both been shot before her pregnancy: The Pretty Woman star wouldn’t truly carry a film until 2010’s Eat Pray Love.

There was, perhaps, no better vehicle to reintroduce Roberts to 21st-century audiences than this big-screen adaptation of Elizabeth Gilbert’s best-selling memoir. The actor’s ability to “come across as both otherworldly and accessible,” as Entertainment Weekly put it at the time, made her a perfect fit to play Liz, a woman who decides to leave it all behind (including a broken marriage) and go on a trip to find herself. She goes to Italy to eat and to India to pray, and ends up finding love in Indonesia. With Roberts appearing in pretty much every scene, and the action set against such beautiful scenery, the film was a treat for fans of the actor who’d missed seeing her on the big screen. Indeed, writing for the Boston Globe, Wesley Morris best encapsulated the critical consensus about the film: “Is it a romantic comedy? Is it a chick flick? This is silly, since, in truth, it’s neither. It’s simply a Julia Roberts movie, often a lovely one.”

Though that film was a financial success, grossing over $200 million worldwide, for most of the mid-2000s to 2010s, Roberts steered clear of high-profile projects, opting instead for more meatier, more dramatic roles. Part of this may be that audiences haven’t flocked to Julia comedies the way they used to. Her 21st-century stabs at rom-coms have mostly been box office disappointments. The corporate espionage–themed Duplicity (2009), which made perfect use of her crackling chemistry with Clive Owen, and the Tom Hanks’s starrer Larry Crowne (2011) both failed to gross more than $40 million. For comparison’s sake, Pretty Woman grossed nearly $180 million back in 1990, while her reunion with Gere in Runaway Bride made $150 million in 1999. But mostly it’s the fact that Roberts seems excited to take on roles that challenge her and get her to explore new facets of her talents. She was never one to have been content being merely a movie star: “[It's] too narrow a field of purpose,” she told W magazine back in 2002.

As winning as laughing Julia can be, there is something very rewarding about seeing her channel her inner anger and burrow her iconic cackle into furrowed brows and angry screams. There are many thrilling moments in Closer, for example. But hearing Roberts, worn-down yet suddenly fed up, yelling, “He tastes like you but sweeter!” at a self-satisfied Clive Owen (here playing her husband, demanding she explain her adultery) is delicious. Similarly, seeing her lunge at Meryl Streep (of all people!) in 2013’s August: Osage County after spewing a four-letter-filled tirade is a rare treat. It explains why Murphy cast her as Dr. Emma Brookner in 2014’s The Normal Heart; her righteous anger matches that of Larry Kramer (played by Mark Ruffalo) in that AIDS drama. The American Horror Story director understood that Roberts’s anger has the power to jolt you awake. Part of that is knowing that when she’s blowing up onscreen, she’s exploding the “America’s sweetheart” image that has for so long defined her. Who knew the Notting Hill star could play bitter so well? Or that she’d so revel in exploring angry women?

At first glance, Roberts’s new Amazon project, Homecoming, feels like a change of pace. It is, after all, her first foray into episodic television, in a genre that’s rarely felt well-suited to her talents (the less we talk about Conspiracy Theory the better). But upon a closer look, the 10-episode show is all but designed to showcase what the actor does best, even using her knack for crackling chemistry with her onscreen partners as the keystone of its drama. Roberts plays Heidi Bergman, a caseworker who’s tasked with helping military veterans process their experiences and readying them for their impending civilian life. Or so she tells Walter Cruz (Stephan James) upon their first meeting. As it turns out, there’s more to the story than what Heidi tells and has been told.

A potboiler of a thriller, Homecoming, adapted for TV by Mr. Robot showrunner Sam Esmail, borrows a page out of her Oscar-winning role, similarly depending on Roberts’s offscreen persona to build out its plot. Only, where Erin flashed her teeth to get what she wants, her Heidi rarely smiles — neither in the present-tense narrative, when she’s waiting tables in a dingy restaurant called Fat Morgan’s, nor in the flashbacks where we see her running the Homecoming program with an almost pitying sense of self-seriousness. Roberts’s Heidi is so jaded (in the present) and so driven (in those flashbacks) that rather than the actor’s characteristic megawatt smile, we’re treated to her just-as-effective perma-frown. So committed is the show to plumbing Roberts’s dramatic chops that it all but avoids deploying her laughter. At one point, when Heidi finds herself the butt of a boyish prank and erupts into a laugh, the shot cuts her right off as if it knew the infectious power of a full-bodied Roberts cackle. Nevertheless, the mere hints we get of a happier Heidi, of the possibility of what her life could be, are enough to keep us guessing as to how she ended up at Fat Morgan’s after she was so devoted to the corporate world that funded Homecoming. Moreover, Heidi’s sense of growing paranoia and her attendant attempts to right the narrative around her and take on yet another corporate entity are rooted in that very same righteous anger that Murphy so enjoys.

Of course, it’s not been all rage-riddled women as of late. During the last decade, Roberts has also showcased soft riffs on motherhood in Valentine’s Day, Wonder, and, yes, even Mother’s Day. They’ve no doubt been informed by her own experiences at home (her two oldest kids are now teenagers). But even as they aim for a lighthearted and heartwarming tone, these films have all been tinged with more melancholy than the buoyant rom-coms that made her a box office star in the ’90s. They’re more bittersweet than what those of us who grew up with Runaway Bride and America’s Sweethearts could ever have expected from her.

Her latest film, Ben Is Back, sits squarely within this new mini Roberts canon. The Christmas-set movie follows Holly Burns (Roberts as the mother of the titular character played by Lucas Hedges) struggling with how to handle her eldest son, who has a drug addiction, when he shows up unexpectedly at her home for the holidays. When she first sees him, Holly all but bursts into tears of joy — tears she later wipes away as she prepares the house for having someone recovering from addiction around. Despite her sunny disposition (“Everyone is so nice,” she remarks later when she has to rush Ben to an AA meeting), she hides her jewelry and the various pill bottles in the family bathrooms. It’s a sign she’s more than wary about her son’s motivations. Equally tender and assertive, fueled at times by frustration and anger and even given a cemetery scene to rival Sally Field’s in Steel Magnolias, Roberts plays Holly as a mother willing to do everything for her child, knowing she might break herself in the process. It’s a performance that builds on the goodwill the actor has amassed for 30 years, the inherent sense of goodness that led many to want to anoint her as the country’s favorite sweetheart.

The most hilarious example of this newly public devil-may-care Julia, though, wasn’t even a performance for the cameras. At the nontelevised 2009 Lincoln Center gala tribute to Tom Hanks, Roberts took the stage to celebrate her longtime friend (and Larry Crowne director) with a speech whose central thesis was “Tom Hanks, what the fuck?” In between praising him for his work in Bosom Buddies and his ability to make everyone in the room feel at home, Roberts’s off-the-cuff remarks found the actress in her element, cursing up a storm while cracking herself up over the fact that she was fucking wearing the same dress as Hanks’s publicist. (“You at the airport with the accent: That was a pass for me,” she ribbed Hanks for his performance in The Terminal.)

Since her Oscar win she’s leaned heavily into two archetypes that run counter to the contrived myth of the “sweetheart” — the angry woman and the loving mother. Onscreen, her angry women flip the script on what we expect of “America’s sweetheart,” giving us characters who opt to not keep their emotions in check and instead use them to voice their ire at the world, at their families, at their loved ones. Her mothers, in turn, offer insights into what loving caregivers can look like onscreen, asking us to do away with the youthful image of Roberts that the sweetheart label demands.

That mix of bitter and sweet may well be the reason that, while she doesn’t command the record-breaking paychecks she once did, she’s been able to carve a niche for herself in prestige pics that make perfect use of her charm in new ways. ●

Manuel Betancourt is a New York City-based queer writer and a lapsed academic. He’s a regular contributor to Remezcla, the film columnist at Electric Literature, and a monthly columnist at Catapult Magazine (“Movie-Made Gay”). He’s one of the co-authors of the graphic novel The Cardboard Kingdom, a New York Times Summer 2018 Pick.