Katie, a 23-year-old working at a homeless shelter in Virginia, was a virgin until her first year of college. Feeling insecure and “trying to be this cool girl,” she decided to create a Tinder account and embrace hookup culture — an experience she said was sometimes enjoyable, but often wasn’t. “There’s people I’ve hooked up with where they just immediately choked me and I was like, this was not discussed, I don’t know you,” she said. “I’ve had some kooky experiences with men where I was open to [hooking up] at first, then realized, I’m in a place that I don’t know, I don’t know how old you are, I don't know your name, I’m blackout drunk, and that’s obviously not fun.”

During one of these sexual encounters, Katie was raped.

Sharing her stories with women friends, Katie realized she wasn’t alone. (The surnames of people interviewed for this story have been withheld to protect their privacy.) “I’ve had friends who were choked until they passed out, friends who were filmed without their knowledge,” she continued. “It’s fucked up and scary, and it makes you definitely wary of meeting people.”

Now, Katie and her friends are cynical about some of the progressive messages they had received about sex when they were younger. “We all really embraced third-wave feminism and sex positivity, and it impacted us so negatively,” she explained. “Being told that you should be having sex with people you don’t have any relationship with really put it in our minds that sex doesn’t matter. I feel like we all just kinda got fucked over.”

Sex positivity, defined by researchers as “the belief that all consensual expressions of sexuality are valid,” including kinky, queer, polyamorous, casual, and commercial sex, has become a household term. The concept has roots in the 1960s, when activists began challenging cultural norms about sex — especially the idea that unmarried, nonprocreative sex is dirty or shameful. Today, the sex-positive movement promotes bodily autonomy, consent, safer practices, and comprehensive education. The concept has been widely embraced across the English-speaking world, appearing in liberal media, academic studies, schools, nonprofit sectors, and political groups.

But as the concept of sex positivity became more well known, it often appeared without important context. Thoroughly picked over by brands, magazines, and social media, it became shorthand for libertine sexual adventurousness without all the fine print about consent, autonomy, safety, and health. Now, some Gen Z’ers — a generation raised in sex-saturated environments yet also increasingly sexless, according to a recent study — say the concept is outdated, and even harmful.

“I think of sex positivity as a little corny and naive for our time,” said Jo, a 23-year-old civil engineer in Colorado. “I get that it was necessary and a response to repression — and I found it super helpful as I was unlearning anti-sex religious attitudes I was raised around, especially as a bi teenager — but it feels somewhat passé now.”

These days, sex positivity is a mainstream idea. “You just have to look around. On Netflix, there’s a show about a dominatrix and it’s, like, a silly comedy show,” said Sakari Hughes, the communications director for the Center for Sex Positive Culture in Seattle. “In some places, you have drag queen storytimes and no one’s burning down the library; there aren’t people with pitchforks anymore.”

But uneasiness with sex positivity is bubbling to the surface, especially in some Gen Z quarters. “I often see [sex positivity] compared pejoratively to ‘choice feminism,’ ‘empowerment,’ [and] ‘eyeliner so sharp it kills a man,’” said Luna, a 23-year-old grad student in New England who since age 13 has been researching her generation’s attitudes toward sex. “It’s seen as potentially shallow, a repackaging of the patriarchy, and not in the best interests of women, especially young women, because people associate it with casual heterosexual sex, D/s play, and being sexually active online, especially through platforms like OnlyFans.”

The concept emerged during a very different era. “I would trace origins going back to the ’60s and the ‘free love’ movement,” said Dawn Woodard, a board member and former executive director of Sex Positive World, a nonprofit that advances sex-positive ideas. “I would include fights for queer rights — Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, [the 1969] Stonewall riots — making big changes for people being allowed to be how they are and live how they want to live.”

The feminist sex wars of the 1970s and ’80s were another turning point, which involved a split between radical and liberal feminists on issues like pornography, sex work, support of trans women, and BDSM. Liberal feminists adopted the label “pro-sex” during this time, and Gayle S. Rubin’s 1984 essay “Thinking Sex” was highly influential, particularly its “charmed circle” model of sexual hierarchy. Rubin argued that society treats some sex as “good, normal, natural, blessed” (i.e., that which is heterosexual, married, monogamous, procreative, noncommercial, in pairs, in a monogamous relationship, of the same generation, private, vanilla) and sex in the “outer limits” as “bad, abnormal, unnatural, damned” (i.e., homosexual, unmarried, promiscuous, nonprocreative, commercial, alone or in groups, casual, cross-generational, public, with pornography, with manufactured objects, sadomasochistic).

Throughout the ’90s and ’00s, the term “sex-positive” came into widespread use. Activists like Carol Queen and Annie Sprinkle carried the torch of pro-sex feminism, and organizations like the Center for Sex Positive Culture and Sex Positive World emerged. It reached a wider audience through feminist and progressive blogging, popular advice columns like Dan Savage’s Savage Love, and Tumblr, which became synonymous with a strong social justice sensibility and sexual freedom and exploration.

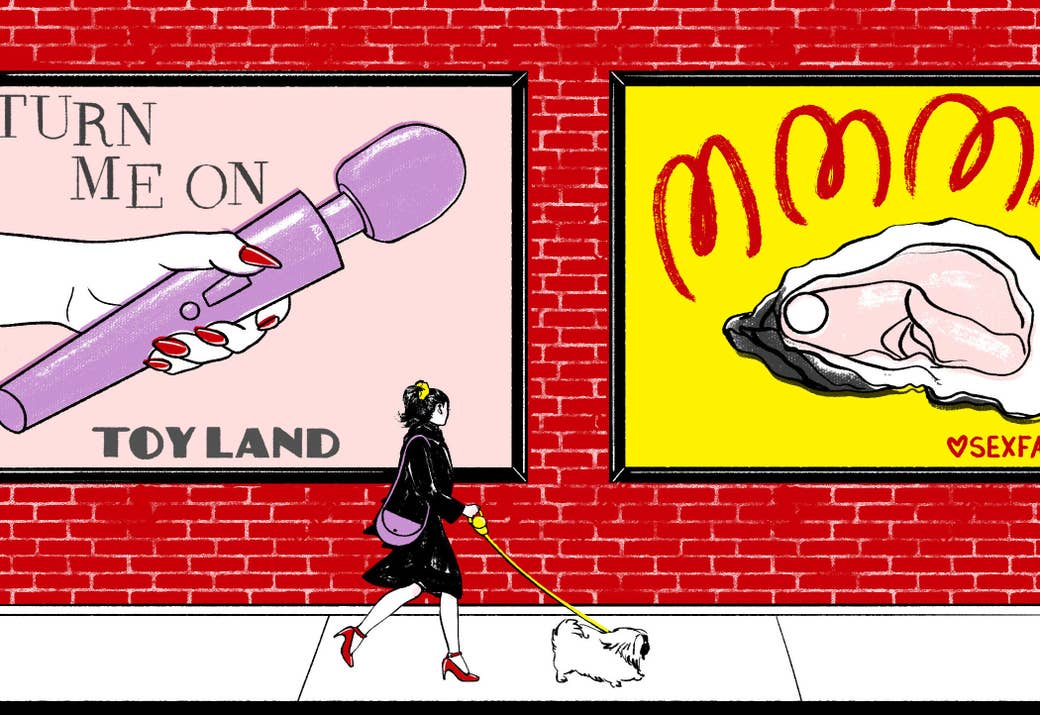

Naturally, brands got in on the action once sex positivity became less of a fringe concept. The sex tech sector sought to capitalize on it, culminating in sex toy billboards proclaiming messages of empowerment, while brands like Durex positioned themselves as activists aligned with the cause.

In large part, it’s thanks to the sex-positive movement and its predecessors that queer sex and unmarried sex have drastically lost their stigma since the 1960s, that there are social norms against slut- and kink-shaming, that people working in the sex industry are routinely referred to as “sex workers” instead of more derogatory terms, and that millions of people feel less ashamed of their harmless sexual tastes. “People don’t believe there’s something inherently wrong with having anal sex, say, or spanking,” Hughes said. “That’s not even a thing anymore.”

And the movement is still focused on liberating the other kinds of sex that Rubin identified as being in the “outer limits.” “[We’re] making space for people who don’t fit into the model of being cisgender, people who do not identify as straight, and people who seek a different relationship style from a monogamous marriage,” said Jamie Cawelti, executive director of Sex Positive World. (These days, though, most sex-positive advocates stop well short of one thing Rubin did: defending adults who want to have sex with minors.)

But the idea that “outer limit” sex still needs to be liberated seems strange to certain zoomers, whose world is one of queer liberation, #kinkTok, Teen Vogue guides to anal sex and hookups, OnlyFans, Instafeet, sex-positive YouTubers like Laci Green, TV shows like Bonding and Sex Education, and, of course, all manner of freely available porn. “[On TikTok], I see a lot of people talking about what they do with their partners, like specific [sex] acts,” Katie said. “I see a lot of people talking about sex work and, especially with OnlyFans, really glamorizing it.”

“You see such a huge difference between an older generation that has a lot of baggage about sex and repressed sexuality,” Hughes said, “and then a younger generation who’ve seen it before on the internet or don’t have that repression inside them.”

One example of this change came earlier this year, when actor Armie Hammer was accused of rape and physical and emotional abuse by two women. Leaked screenshots of explicit DMs that Hammer had allegedly sent (he denied they were legitimate) revealed sexual fantasies about rape, knives, torture, and, most notoriously, cannibalism. Several major liberal publications made a point of refusing to treat his sexual preferences as funny, disgusting, weird, or automatically harmful.

“The problem is not that he has a cannibalism kink,” Nicole Froio wrote at Bitch Media. “It’s the way he crossed boundaries again and again, coercing his victims into engaging with his fetishes.” Rolling Stone and Slate interviewed self-professed cannibalism fetishists, all of whom echoed Froio’s point. Cosmopolitan enlisted a fetish educator to explain how a consensual cannibalism kink would work. “Instead of shaming people’s fetishes,” she cautioned, “we should be teaching them to share their interest in a way that doesn’t harm others.”

Sex positivity has a dedicated opponent in Louise Perry, a UK-based activist against sexual violence. “[Sex-positive] ideology liquefies all norms,” she told BuzzFeed News, “leaving only the principle of consent, and then insists that every consensual sexual act is necessarily good, refusing to recognize that consent is not binary. It is often subtly coerced, to varying degrees.”

Perry, who used to work in a rape crisis center, now campaigns with the UK-based We Can't Consent to This, which draws attention to the “rough sex” defense: namely, when men who kill or seriously injure women claim the victim consented to the violence during sex. “To date, every defendant relying on this defense tactic has been male,” Perry said. “The mainstreaming of BDSM has led to more and more defendants successfully using this tactic, not only in the UK but worldwide.” We Can’t Consent to This has documented almost 60 cases where men who killed women raised a defense of this nature.

In Perry’s view, this campaign highlights the practical problems that occur when consent is the only sexual norm left standing. “If it's legally possible to consent to serious violence, then the task that the prosecution is faced with is to prove beyond reasonable doubt that there was no consent, which is an inherently difficult task, because either the victim is dead and can't testify or you have a 'he said, she said' scenario with no other witnesses,” she said. “Not only would courts have to be sure that the defendant committed the violent act, they would also have to be sure that the victim wasn't 'asking for it.’”

Dawn Woodard of Sex Positive World is keenly attuned to the problem of sexual abuse in the kink community, a topic they said occupies their thoughts because “there’s a lot of complexity.” Woodard stressed that promoting sex positivity is not the same as condoning harmful behavior. “There are lots of toxic forms of kink; there are lots of ways in which you can see abuse masquerading as kink, and that’s super problematic,” they said. “But I don’t think it negates the importance of sex positivity. I think sex positivity can actually be the answer to those problems, in empowering people to be able to communicate better with their partners, to negotiate better.”

Woodard sees sex positivity as an antidote to a still prevalent rape culture, which trivializes sexual violence. They said that a gatekeeper model of sex still exists: Masculine people are encouraged to pursue sex and “keep pushing” reluctant feminine partners, who are in turn expected to vigilantly guard access, remaining silent about their own desires. “Instead of sex being a thing that is mutual and desired by both people, it’s seen as this con game, which is so limiting,” they said. “It puts people in these weird roles, very gendered, where [feminine people] are not supposed to say yes to things; you’ve got to say no.”

But critics of sex positivity say women and girls face the opposite problem today: sustained social pressure to always say yes to sex, especially if it’s kinky and casual. “When I was 17 or 18 and newly emerging into sexual situations, I did a lot of things in the name of sex positivity that I didn’t necessarily enjoy,” said Charlotte, a 23-year-old student in the UK. “I got the impression that sex positivity was about doing all and everything because there is an emphasis on it being kink-friendly. And as a younger person, I thought that meant I owed it to myself as a sex-positive person to try everything, almost blindly. A lot of rough sex, reclaiming the term ‘slut,’ and the idea of dom/sub became very central to my idea of how cishet sex worked.”

More people like Charlotte are speaking out about their experiences. “A lot of critiques of sex positivity are coming [from] people having bad experiences being sexual at a young age, especially with being pushed beyond their comfort zone and feeling they had to perform in order to be ‘cool,’” Luna said. A sobering British study of 130 teens found that teenage boys "were expected to persuade or coerce reluctant partners" into having anal intercourse, for example, and that girls were submitting to unwanted, painful anal sex.

Some zoomers are blaming sex positivity. “There's especially a concern about people being ‘groomed’ using sex-positive language,” Luna said, “and some people think that can happen on a societal level — i.e., people are ‘groomed’ or coerced by a culture of sex positivity.”

Katie, the 23-year-old in Virginia, described sex positivity as a kind of long con. “It feels like we were tricked into exploiting ourselves [and] tricked into thinking it was our idea,” she said. “I would say I gathered this mostly from media, Sex and the City, Girls — HBO somehow did a number on me — books, social media… You read a lot about [sex positivity] on Tumblr, you read a lot about it on Twitter when you were in high school, [and] it gets really ingrained in your brain that you need to be comfortable having sex with someone you’re not committed to. I think in my feeble 18-year-old mind, it was probably not what I needed to hear.”

She half-joked that sex positivity now feels like a cross between a male conspiracy and a cynical marketing ploy. “I really think it’s overlord men, somehow,” Katie laughed. “There’s always a Don Draper behind it.”

Sex-positive activists Hughes, Cawelti, and Woodard say their work is far from done. “There are still a lot of battles that do need to be fought, especially with sex education,” Hughes said. “[The US] is just in flux at this point, and it might shift either way depending on who the next president is. There are definitely some places in the country where I would say sex positivity is on the rise and some places where it hasn’t changed in like 50 years.”

But Perry, the activist, sees sex positivity as dangerously preoccupied with an old — and already weak — enemy. “I object to the sex-positive movement because I see it as reactionary,” she said. “Its sole objective is to reject the bourgeois sexual norms of the past, but it can't recognize the harms of the modern ‘anything goes’ attitude towards sex.”

Among Gen Z’ers, the term can invite wary caution. “When people talk about sex positivity around my age and especially younger, it's usually something like ‘the idea that sex is good and easy,’” Luna said. “People preface their critiques about the safety of kink spaces or concerns about sex as self-harm with things like, ‘Even though sex positivity might portray things this way, there are X risks’ or ‘Don't let sex positivity trick you into thinking Y is okay/normal/safe.’”

Yet despite their negative experiences, neither Charlotte nor Katie has given up on it entirely.

“I do still feel sex-positive but I would say in a more understated and accepting way,” Charlotte said. “Rather than making it a big part of my public personality, it is something I choose to keep more private, venturing into sexual relationships and situations with others because I want to, not because it’s trendy on Tumblr or any other social media.”

“I think there’s a place for [sex positivity], and overall it’s a great concept and really necessary,” Katie said, “but it has to be done in a careful way.” ●