Angels in America

The word “relevant” was lobbed around with dangerous frequency in 2018: How often can you be told a show is “timely” before your eyes start to glaze over? What was fascinating about director Marianne Elliott’s gorgeous revival of Angels in America is that it was stunningly relevant — while also being firmly grounded in the past, both the time period in which it’s set (the mid-’80s) and when it first premiered on Broadway (the early ’90s). In many respects, the success of Tony Kushner’s play is its specificity: By writing something so distinctly about the height of the AIDS crisis, with references to Reagan-era conservatism and a starring role for notorious lawyer (and Trump mentor) Roy Cohn, the playwright created a work that is authentic enough to be timeless. That doesn’t mean that every production of Angels in America will work as well as the recent Broadway revival did — this is, after all, a beast of a show to pull off. But Elliott’s production never felt overwhelming or unwieldy, thanks in large part to an exceptional cast, including Andrew Garfield and Nathan Lane, who won Tony Awards for their work, and Denise Gough and James McArdle, who should have. It’s a true injustice that McArdle wasn’t even nominated: His Louis was one of this production’s strongest assets, imbuing a very challenging character with much-needed compassion.

Angels in America closed at the Neil Simon Theatre on July 15.

The Cher Show

The bio-musical is one of Broadway’s most maligned genres, and with good reason. These shows tend to be awkward, stilted, and annoyingly laudatory toward artists that haven’t really warranted two and a half hours of unchallenged praise. And yes, The Cher Show — which tracks the career of the eponymous icon from her youth as Cherilyn Sarkisian to her 87th reunion tour, currently happening in a city near you — is pretty consistently effusive about the diva at its center. But also, this is Cher; some gushing is to be expected! Besides, what distinguishes The Cher Show from its predecessors is that the musical (much like Cher) has a sense of humor about itself. Yes, it’s occasionally ridiculous, but always with tongue planted firmly in cheek, frequently winking at the audience if not directly addressing them. The three Chers — Stephanie J. Block, Teal Wicks, and Micaela Diamond play Cher at different stages of her life — interact with one another and sometimes step into one another’s scenes, making for some truly surreal moments. Also surreal: a dance ballet that recalls Oklahoma!’s, in which Cher is forced to choose between Sonny Bono (Jarrod Spector) and Gregg Allman (Matthew Hydzik) while the men sing “Dark Lady.” It’s the kind of thing that has to be seen to be believed — as are the Bob Mackie costumes and the always fabulous Block’s career-best performance.

The Cher Show is currently running at the Neil Simon Theatre.

Dance Nation

There have been a few plays this year about women discovering their bodies, and the agony and ecstasy therein. Collective Rage: A Play in 5 Betties was about adult women reckoning with their gender and sexual identity, while Usual Girls (running at Roundabout Underground through Dec. 23) is a coming-of-age story about the dangers of navigating a racist and patriarchal society as a nonwhite woman. But Dance Nation may have been the purest articulation of growing up and coming to terms with the power and peril of female sexuality (an experience I can never fully comprehend). Clare Barron’s poignant, thrilling play followed a dance group of six young teen girls (and one boy), all of them played by actors much older than 13. But the age disparity between performer and character never took away from the stark reality of the piece, which balanced a heightened theatricality with painfully honest, emotional truths. There was real pathos to these kids’ problems, like the budding rivalry between best friends Zuzu (Eboni Booth) and the more talented Amina (Dina Shihabi). In Dance Nation, these girls learned to translate their wildly vacillating emotions into movement, but also how to explore their sexual desire, evade predatory men, and grapple with an existential dread they don’t yet have the language to articulate. Much like puberty itself, it was beautiful and terrifying.

Dance Nation closed at Playwrights Horizons on July 1.

Fairview

It is easy for white people in theater, of which there are many, to talk about making room for nonwhite artists — writers, directors, actors, audience members. It is far more difficult to actually follow through with that. Making space requires sacrificing your own; listening requires shutting up. Fairview was actively concerned with how to make this happen: Jackie Sibblies Drury’s play articulated, first subtly and then less so, the way white audiences infringe on black artists telling their own stories. It made some uncomfortable — even those who praised it — but any work that asks the white people watching it to acknowledge their privilege and ultimately relinquish their seats is bound to ruffle some feathers. What began as a fairly broad comedy about the Frasier family coming together to celebrate their grandmother’s birthday became a searing indictment of how challenging it is for white people like myself — however well intentioned — to not inflict our perspectives and biases on stories that don’t belong to us. There are many ways that theater can have value, and one of them is not necessarily better than the others, but there is something particularly potent about theater that can make you feel this level of unease, especially if you are a member of a group who is rarely made to feel that way. Some plays succeed by giving you comfort; others succeed by getting under your skin.

Fairview closed at Soho Rep on Aug. 12.

The Ferryman

When you see as much theater as I do, it’s hard to get hyped about a play that runs 3 hours and 15 minutes — with 0ne intermission! — but The Ferryman is one of those rare epics that somehow manages to fly by. After a massively successful run in London, where it won the Olivier Award for Best New Play, The Ferryman opened on Broadway to rapturous reviews that underscored how easy it is to lose yourself in this rich, lyrical work. Jez Butterworth’s play, which centers on the Carney family at their farmhouse in 1981 Northern Ireland, catches you off guard with its emotional depth and unexpected brutality. It has been compared to August: Osage County, another lengthy, sprawling family drama, but it’s really a contemporary take on Greek tragedy. (The title of the play is a reference to Charon in Virgil’s The Aeneid.) To try to describe the plot in more detail is senseless, as is an attempt to outline all the characters: There are a staggering 21, not to mention a goose, a rabbit, and a baby. What’s remarkable about The Ferryman is how effortlessly it invites you in. Despite the concerns I had about the heavy Irish accents or keeping track of all the names — Declan and Diarmaid and Oisin — I was hooked by the end of the first hour, and on the edge of my seat by the third. The ending is a stunner, one of the few times I’ve called something “jaw-dropping” and meant it literally.

The Ferryman is currently running at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre.

Head Over Heels

I don’t rank my list of the best theater of the year: It’s just too hard to compare, say, Angels in America and The Cher Show. But if you want to know what show brought me the most joy in 2018, what show I saw over and over again, what show I demanded that everyone I know buy tickets for — that would be Head Over Heels. There are, in fact, few shows that I have ever fallen in love with the way I fell in love with this heartfelt, wickedly funny, and radically queer Go-Go’s musical. Based (loosely) on Sir Philip Sidney’s Arcadia, Head Over Heels is a farce in which Pamela (Bonnie Milligan) falls in love with her handmaiden Mopsa (Taylor Iman Jones); Philoclea (Alexandra Socha) enters into an illicit affair with the shepherd Musidorus (Andrew Durand), disguised in drag as an Amazon warrior; and everyone ultimately falls somewhere on the LGBTQ spectrum and rejects the gender binary. It’s relentlessly fun, because of course it is — they’re singing Go-Go’s hits like “Vacation” and “Our Lips Are Sealed” — but it’s also a major step forward for Broadway, where queer representation has largely been limited to cis gay white men. Peppermint, who is trans and a former RuPaul’s Drag Race contestant, plays Pythio, the nonbinary Oracle at Delphi who uses plural pronouns. Head Over Heels is expanding the minds of Broadway audiences without ever losing the beat.

Head Over Heels is running through Jan. 6 at the Hudson Theatre.

The House That Will Not Stand

Federico García Lorca’s The House of Bernarda Alba has been adapted before, but never the way that Marcus Gardley did in his invigorating 19th-century New Orleans–set The House That Will Not Stand. Lorca’s Bernarda Alba becomes Beatrice Albans (Lynda Gravátt), a free woman of color at a time when the United States’ purchase of the Louisiana Territory — and the imposition of US law — would soon eliminate that class of person entirely. Beatrice is desperate to secure ownership of her home before she’s no longer legally able to do so; she’s also struggling to maintain control of her three daughters and her slave, Makeda (Harriet D. Foy), the play’s breakout character. The House That Will Not Stand likely confounded some theatergoers: The tone was deliberately hard to pin down, moving from bawdy comedy to heavy drama, with a recurring drumbeat infusing the proceedings with a sometimes overwhelming intensity. At times, it felt tied to its time period with realism, while in other moments, the characters seemed to see beyond themselves and into our modern existence. But that’s what I love about Gardley, who also gave us X: Or, Betty Shabazz v. the Nation, which I saw in January and nearly included on this list. His work unpacks history from a contemporary perspective, delivering stirring thematic relevance with theatrical flair.

The House That Will Not Stand closed at New York Theatre Workshop on Aug. 19.

The Jungle

When someone asks me what theater can do that film and television cannot, I will point to The Jungle, a piece of art about the refugee crisis that is immersive and affecting in a way that no other medium could match. Your ticket earns you a spot inside the Calais Jungle migrant camp, or rather, a recreation of it: I was seated in Sudan. The show unfolds quite literally around you, with the characters sometimes behind you, sometimes at your side. There are moments when the action is happening directly in front of you, but nearby you can hear other characters speaking in a language you don’t understand. There are many variations of immersive theater, but few shows come close to making you feel this immersed — and for the purpose of making you walk in the shoes of people so many of us are too often able to push out of our minds. The Jungle is an enveloping, at times emotionally exhausting experience, but it’s not without humor and joy: At one point, there is a jam session among residents of the Jungle, each bringing their own distinctive rhythm and style of music to the scene, and it’s one of the most blissful moments I’ve witnessed at the theater. And if the play as a whole is ultimately bleak, if you do cry throughout, if your shoes are dirtier when you’re leaving than they were when you came in, that’s a small price to pay to step outside your likely more privileged existence and into someone else’s world.

The Jungle is running through Jan. 27 at St. Ann’s Warehouse.

I Was Most Alive With You

There were actually two casts who performed I Was Most Alive With You: the cast on the main stage, who used a combination of spoken English and American Sign Language to communicate, and the shadow cast above them, who performed the play entirely in ASL. It was essential that Craig Lucas’s play be accessible to the widest audience possible: There were so many big, important ideas on display here — about addiction and faith, but also, on a more specific level, about the ways the Deaf and hearing communities speak to each other. The play Children of a Lesser God, which was revived earlier this year, touched on similar ideas, but it felt outdated in its simplicity. I Was Most Alive With You was messy and raw, and so much more of the moment. (It’s worth noting that the Children of a Lesser God revival had ASL translation and supertitles, reflecting important strides in accessibility on Broadway.) In Lucas’s play, Ash (Michael Gaston) is a hearing TV writer and Knox (Russell Harvard) is his deaf son; they are both in recovery from addiction. The Book of Job becomes a thematic throughline to the work as the family and those around them — Ash’s wife Pleasant (Lisa Emery), Knox’s would-be boyfriend Farhad (Tad Cooley), among others — are tested in increasingly dramatic ways. There are times when the play risked going over the top, but its pathos and grace fully grounded the biblical grandeur of its plot.

I Was Most Alive With You closed at Playwrights Horizons on Oct. 14.

Lewiston/Clarkston

Lewiston/Clarkston is ostensibly two plays, but really it’s three. There’s Lewiston, about a descendant of Meriwether Lewis who is selling off her family’s land and barely scraping by selling fireworks on the side of the road; there’s Clarkston, about a descendant of William Clark who is struggling to connect with his roots as he faces an uncertain future; and then there’s the communal meal between the two stand-alone 90-minute plays. The plays were written by Samuel D. Hunter — the dinner (or lunch, if you attended a matinee) is obviously unscripted. And yet, it’s an integral part of the experience, a reminder of the often unspoken bonds between ostensible strangers and a reflection of the brilliantly conceived intimacy of this production. Lewiston/Clarkston is performed at a theater stripped bare: You sit on folding chairs, and while there is a stage, it’s only used briefly. Intimacy is, in fact, a staple of Hunter’s plays, and not only because they’re often performed in these smaller off-Broadway venues. His work probes deeply into the emotional interiority of his characters: You get close to them, and it’s a credit to Hunter’s writing that they feel like real people with fully realized lives, even when we’re seeing just a snapshot of that. There are only six characters total in Lewiston/Clarkston (not counting the fellow patrons I shared a meal with), and they are some of the most potently developed I saw onstage in 2018.

Lewiston/Clarkston closed at Rattlestick Playwrights Theater on Dec. 16.

The Lucky Ones

When I was deciding what to put on my list of the best plays and musicals of 2017, I had no doubt about including Hundred Days, an autobiographical musical from Abigail and Shaun Bengson, who perform together as the Bengsons. In my write-up of the show, I said that their music “is as exhilarating as ever, and the wince-inducing honesty of their lyrics pairs well with the deeply personal nature of the story they’re sharing.” I could have said the same about The Lucky Ones, which was both a follow-up to Hundred Days and something of a prequel, delving into the familial trauma that Abigail only alluded to in their previous musical. The Ars Nova production was more traditionally theatrical than Hundred Days, with actors performing alongside the Bengsons and taking on the roles of Abigail’s family members. The expansion of the story only deepened my love for the Bengsons’ distinctive warmth and storytelling flair. The phenomenal cast — which included Adina Verson (a standout in Indecent and Collective Rage) and Damon Daunno (who blew me away in Oklahoma!) — was a major asset. But the real power of a musical by the Bengsons continues to be their willingness to fully expose the darkest parts of themselves: the confusion, the insecurities, the lasting scars. The Lucky Ones was not as easily digestible as Hundred Days, but that’s precisely why I can’t get it out of my head.

The Lucky Ones closed at the Connelly Theater on April 28.

Oklahoma!

The lights stayed up at St. Ann’s Warehouse throughout director Daniel Fish’s miraculous Oklahoma!, so I could see the faces of my fellow theatergoers, and I observed something equal parts amusing and distressing during the climactic title number. Some patrons were joyously clapping, either mouthing the words or singing along; the rest of us were frozen in horror, still processing what we had just witnessed. I don’t want to give too much away — those who missed this Oklahoma! will have a chance to see it when it transfers to Broadway in March — but the disparity in reactions speaks to the brilliance of this production, which takes something wholesome and familiar and exposes the ugliness underneath. Fish’s Oklahoma! is harrowing, dripping with blood and sex, a far cry from what most theater audiences think a Rodgers and Hammerstein show should be — that would explain their stubborn, inappropriate glee. But it’s not reinventing the classic musical so much as laying bare the subtext that’s been there all along: the class divides, the male entitlement, the inescapable violence of territory life. There are modern touches, of course, namely a more avant garde dream ballet and inclusive casting that reflects a more realistic diversity of bodies. But Oklahoma! is gritty and brutal because it’s an American classic, and, well, have you met this country?

Oklahoma! closed at St. Ann’s Warehouse on Nov. 11.

The Prom

Confession: The first time I saw The Prom I wasn’t sure what to make of it. Sure, it’s cute, but it’s a hard show to pin down, perhaps because it’s really two different shows. The first is about Emma (Caitlin Kinnunen), a lesbian who causes a major controversy at her high school just because she wants to take her girlfriend to the senior prom. The second is about a group of washed-up actors — Dee Dee Allen (Beth Leavel), Barry Glickman (Brooks Ashmanskas), Trent Oliver (Christopher Sieber), and Angie Dickinson (Angie Schworer) — who take up Emma’s cause because they need the good publicity that comes from activism. The Emma show is a more straightforward, sincere high school musical; the actors show is a heightened, satirical cavalcade of theater in-jokes. But the second time I saw The Prom, it clicked for me — who cares if this musical feels like two shows in one when both shows are this entertaining? It’s got humor and heart, sweeping ballads about high school love, and full-blown parody numbers that only theater nerds will get. Moreover, the actors are exceptional, the score is catchy, and the message of tolerance is perfectly timed. Who is this musical for? I wondered the first time I saw it. I’m glad I saw it again so I could discover the answer: This show is for me. And that’s how I learned to stop worrying and love The Prom.

The Prom is currently running at the Longacre Theatre.

Slave Play

If you want to see an older, mostly white audience nervously shift in their seats, might I recommend Slave Play? The first part of Jeremy O. Harris’s mindblowing new play is explicit and deeply uncomfortable as scenes from the MacGregor Plantation devolve into kinky sexual fantasy. These are things you don’t normally see onstage, and — if the squirming of those around me when I saw it is any indication — these are things not everyone is ready to see. But none of this is for shock value, and despite how it might sound on paper, Harris’s play is not exploitative. The problem with writing about Slave Play is that there’s a fairly major twist early on that completely upends everything that came before it: To share it would be to undermine the thrill of seeing the play with fresh eyes, but to ignore it contributes to a critical misunderstanding of what Slave Play is really about. Already, I feel like I’ve said too much — and, as with Fairview, I recognize that I am not the person who should be praising or defending this work. As Jesse Green wrote in his (spoiler-heavy) New York Times review, “It’s hard for a critic to heed what seems to be its general instruction, at least to white people, to shut up for once and listen.” What I will say about Slave Play is that it demands to be seen, and while this run is sold out, it’s hard to imagine something this sharp, transgressive, and unnervingly funny not having a long life.

Slave Play is running through Jan. 13 at New York Theatre Workshop.

Summer and Smoke

I wasn’t familiar with Summer and Smoke before the Classic Stage Company production: It’s not one of Tennessee Williams’ better-known works, and the play as a whole doesn’t have the enduring power of classics like Cat on a Hot Tin Roof or A Streetcar Named Desire. In terms of plot, Summer and Smoke doesn’t exactly stand out from the rest of Williams’ oeuvre: It’s about a proper Southern woman who ends up losing her innocence and, to some degree, her grip on reality. But director Jack Cummings III’s production gripped me from start to finish. The minimalist staging kept the focus entirely on the exquisite cast, led by Marin Ireland as a minister’s daughter, Alma Winemiller, and Nathan Darrow as her almost-lover John Buchanan. The push-and-pull of their relationship was deeply compelling, with palpable sexual chemistry. Ireland delivered what was easily one of the year’s best performances. In doing so, she once again proved that she is a force to be reckoned with, underappreciated only in the sense that she hasn’t yet been showered with the awards she deserves. Aside from everything else this play had going for it, her Alma — alternating between fragile and ferocious — is the reason Summer and Smoke made this list. There’s little Ireland can’t do, but if Broadway is looking for a leading lady for an upcoming Tennessee Williams production, I have a suggestion.

Summer and Smoke closed at Classic Stage Company on May 25.

This American Wife

I don’t just love the Real Housewives franchise: I live and breathe Real Housewives. My passion for the Bravo series — that would be series plural, as I watch literally every city — is bordering on the unhealthy. Real Housewives may be the only media I consume more of than live theater, and sadly there’s rarely any overlap. (I suppose you could count Real Housewives of Atlanta’s Kandi Burruss in Chicago and Real Housewives of New York’s Countess Luann de Lesseps’s cabaret show at Feinstein’s/54 Below, both of which I saw this year. But I digress.) Put on as part of New York Theatre Workshop’s Next Door series, Michael Breslin and Patrick Foley’s This American Wife was a show I feel like I conjured into existence through sheer force of will. But that would be discounting the genius of Breslin and Foley, who may have even more of a pathological attachment to Real Housewives (and to theater) than I do. This American Wife wasn’t just an excuse for its creators and stars to recite their favorite lines from RHOBH and RHONY — although, yes, it was that — but also a transfixing, thought-provoking exploration of the relationship between gay male identity and the conspicuous consumption of Bravo’s reality programming. It was provocative, hilarious, and (for better or worse) the most I have ever felt seen onstage. If you saw it and didn’t get it, we’re probably not a match.

This American Wife closed at Next Door at New York Theatre Workshop on Aug. 11.

Torch Song

Michael Urie should win a Tony for Torch Song. I don’t like making these write-ups about awards — the Tonys aren’t the arbiter of quality, and so many of the shows I loved this year aren’t even eligible — but I had to put that somewhere. He is great in everything he does, but he has never been better than as gay Jewish drag queen Arnold Beckoff in Harvey Fierstein’s Torch Song. The role was created by Fierstein, but Urie makes it his own: There is so much humor and heart in his performance, moments of physical comedy and monologues of heartbreaking honesty, that it’s impossible not to fall in love with the character, and with the actor who makes him come alive. Urie is not the only reason to see Torch Song. Like Angels in America, the play is something of a time capsule in its depiction of gay life, but it remains so true to life that it feels as important now as it was when it premiered on Broadway in the early ’80s. The cast is strong outside of Urie: The great Mercedes Ruehl will earn deserved accolades for her performance as Arnold’s mother, but attention should also be paid to the overwhelmingly charming Ward Horton, who plays Arnold’s on-again, mostly off-again lover Ed. It’s a shame Torch Song is closing so soon, but the national tour launches next fall, with Urie reprising his role. If you didn’t get to see it on Broadway, don’t miss your chance to let Arnold into your heart.

Torch Song is running through Jan. 6 at the Helen Hayes Theater.

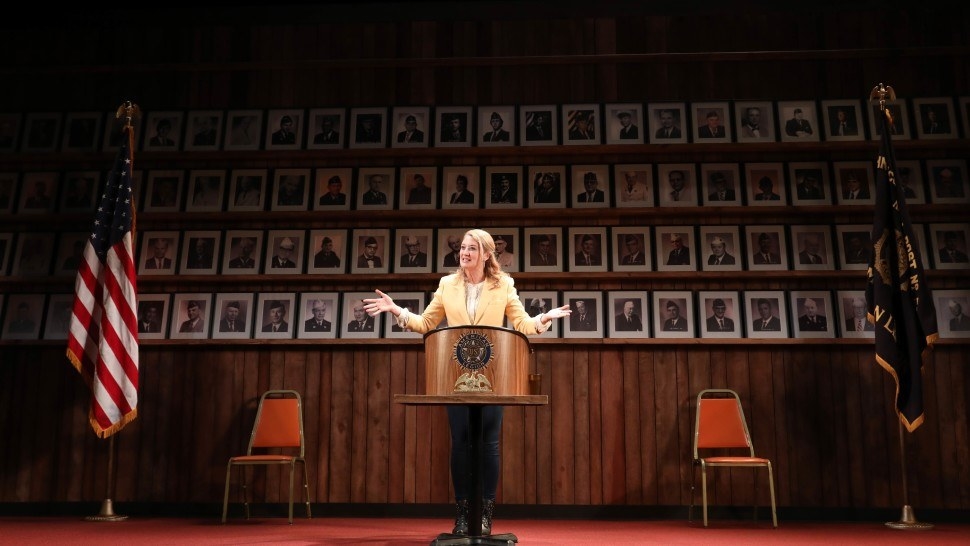

What the Constitution Means to Me

It’s not surprising that one notable critic — I won’t name names, but it rhymes with “Shmen Shmrantley” — said that What the Constitution Means to Me “has the shapelessness of a work-in-progress.” Heidi Schreck’s witty, biting play is structured to feel like a series of tangents, but while it might seem like the woman at its center is going off script, she knows exactly what she’s doing. The brilliance of this work is that it lulls you into a false sense of calm before pulling the rug out from under you with hard truths about the ways a document designed to protect our freedoms has failed everyone but rich white men. Inspired by the speech and debate competitions she excelled at as a teenager, Schreck revisits her youthful passion for the Constitution, and the ways her faith in this hallowed document has faltered over time. Early on in What the Constitution Means to Me, I was surprised to find that I was crying — and as the play went on, I had to work hard to stifle increasingly angry sobs. As Schreck exposed the trauma of her family while rattling off statistics about the everyday violence women face, as she outlined the rights that have been denied to immigrants and indigenous peoples, I felt unspeakable grief. That’s not to say that Schreck’s play isn’t also deeply funny. In those moments of humor — and others of unbearable pain — there is catharsis, the power of a collective theater experience.

What the Constitution Means to Me is running through Dec. 30 at the Greenwich House Theater.