When Pei Ying Yu and Yan Nong Yu learn they have to leave their apartment immediately, it comes as a sudden shock even though they’ve been dreading it for months. It’s January 28, 2015, the day after a blizzard hit Boston. The schools are closed and the governor told commuters to stay home. Along the narrow streets of Chinatown, the owners of grocery shops and bakeries shovel sidewalks while pedestrians climb over snowbanks, everyone displaying the exaggerated courtesy of neighbors getting through a minor disaster together.

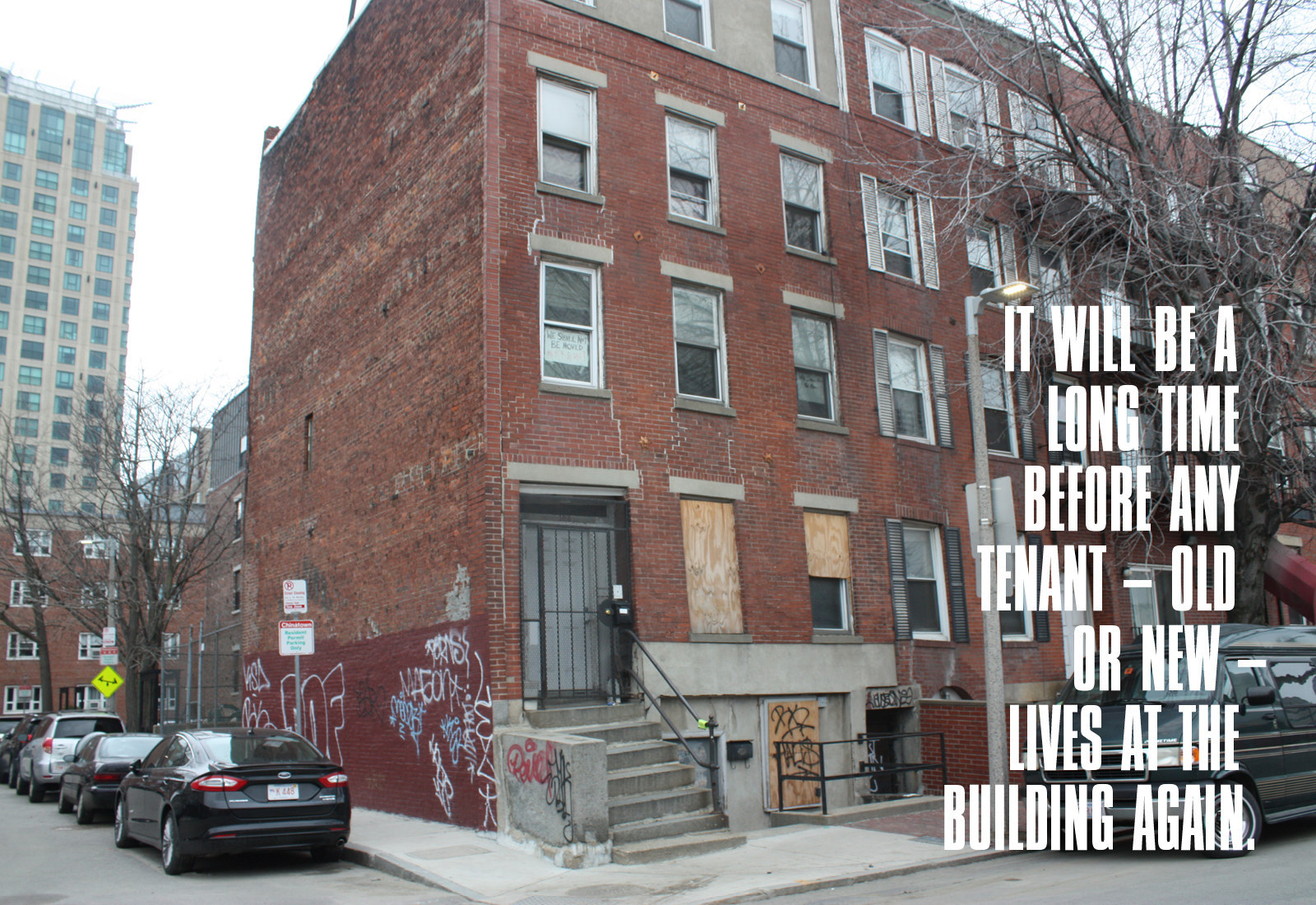

Pei Ying is in her sixties; she came to the U.S. in 2008. Her younger sister followed two years later. Both speak very little English and make under $12 an hour as home health aides. Their apartment, which they’ve lived in since 2013 and share with another roommate, is part of a broken-down row house building at 103 Hudson St. When a new landlord bought the building in mid-January, the Yus knew he’d have a lot of work to do to bring it up to code. That meant he would need to move them, and the rest of the tenants, into a hotel for a while.

The sisters are at their jobs when they get the news. Yan Nong hadn’t been home since the day before — she was snowed in at a client's house. After work, they cram their clothes, clean or dirty, into plastic trash bags and talk about what might happen next. It isn’t just the inconvenience of being temporarily relocated to a hotel that worries the Yus. They wonder if, once they leave their home, they’ll ever be allowed to move back.

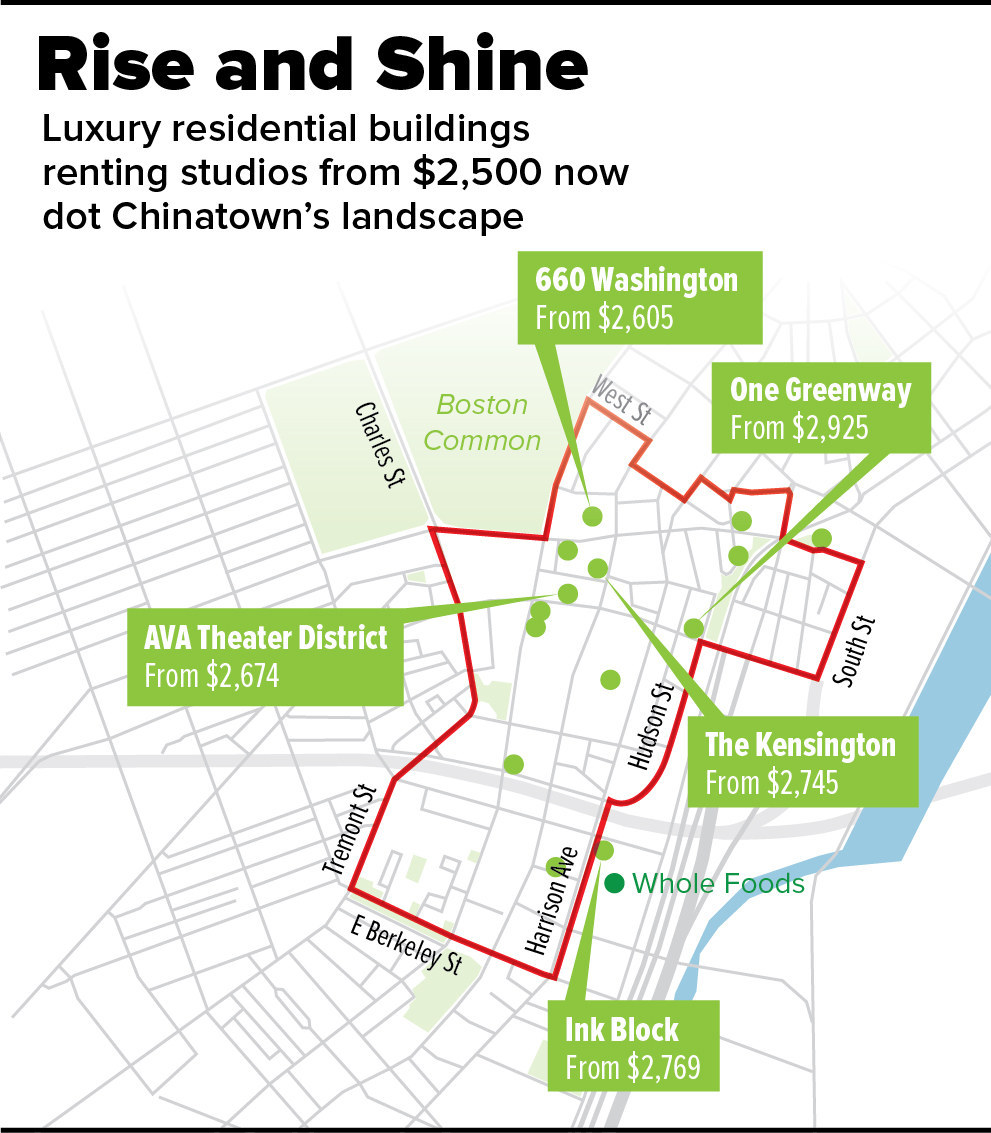

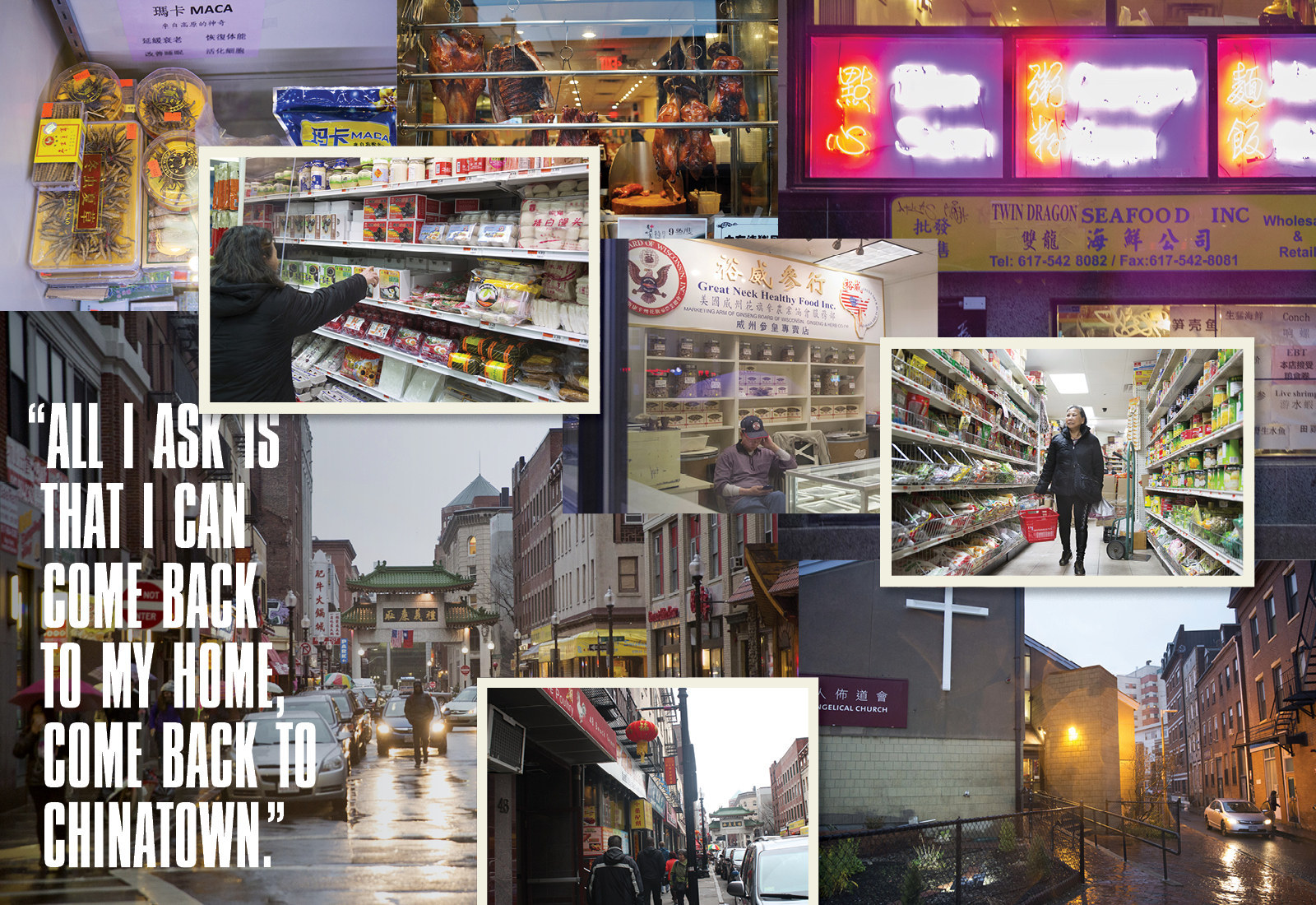

Boston’s Chinatown, home to around 12,000 people, takes up a quarter of a square mile near the center of Boston — an area that’s in the midst of a luxury housing boom. Seven blocks away, a new, towering apartment building, The Kensington, is asking more than $4,000 a month for an 822-square-foot one-bedroom, more than five times the $700 that the Yus and their roommate pay.

While the Yus and their neighbors pack up, community organizer Karen Chen talks with them about their next steps. She and a half-dozen volunteers document the possessions tenants will have to leave behind, make calls to the media, and hand out signs to supporters who joined them: "Stop Corporate Greed" and "This Is Our Home" and "We Shall Not Be Moved."

Chen is co-director of the Chinese Progressive Association, a group that's been at the forefront of a fight to keep Boston's Chinatown from disappearing. The CPA was founded in 1977 to work on issues, from housing to employment, that concerned Chinese-Americans in Greater Boston. Its small headquarters, just a few blocks from the Yus’ home, is often crowded with older Chinese-speaking local residents volunteering or seeking help. It also draws younger Chinese-American volunteers from all over the area, many of them high school and college students who have never lived in Chinatown but have strong ties to the neighborhood through their families.

As the protesters chant and sing in front of the building's steps, the person they’re protesting walks over to stand on the sidelines. Tim O'Callaghan, a former firefighter whose real estate company, First Suffolk LLC, had bought the old brick row house, is visibly flummoxed.

"I just want for you to understand," he tells the protesters. "I’m a humanist. I'm not a pig."

O'Callaghan's a longtime Boston developer, middle-aged with stubble and blue jeans, a pair of reading glasses perched on his baseball cap. He’s built his business for years while serving in the fire department, and since retiring in 2011 he’s been at it full-time.

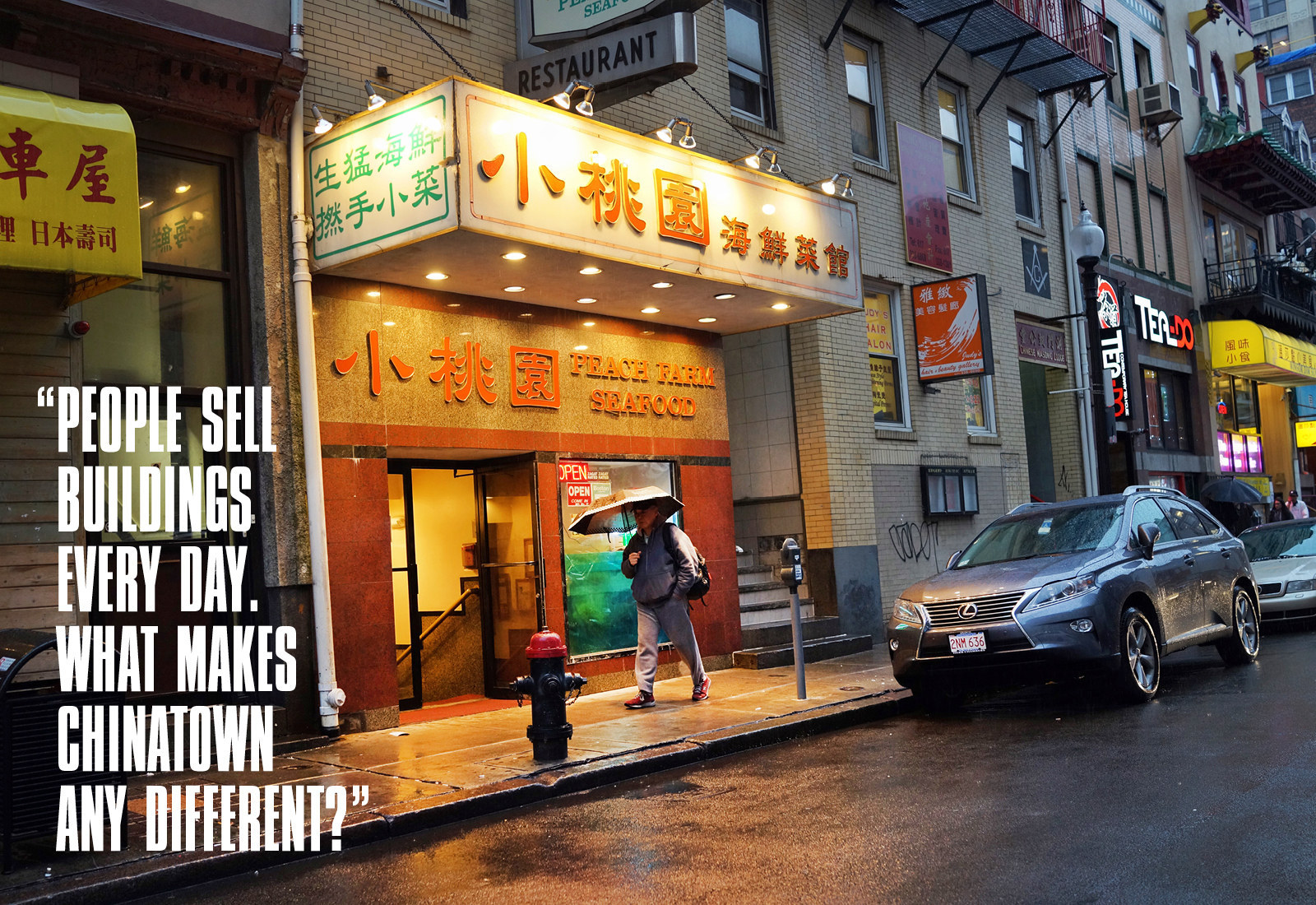

He says the protesters have him all wrong. He’s a good guy. He works 12-hour days. In a different time and place, he says, he'd be standing with the tenants against big, unscrupulous developers. “People sell buildings in South Boston every day in Back Bay,” he continues. “What makes Chinatown any different?” Consequently, “I think this is harassment, what [the protesters] are doing.”

For O'Callaghan, the argument is straightforward: The previous owners left it an uninhabitable mess, so, by rehabilitating it, he’s doing the tenants a favor. "It's a shame a building could sit here 75 years being in that condition,” he explains. No one is debating that part: The city even filed criminal charges against the previous owners on account of the structural violations. What the protesters contest is whether the current tenants will ultimately benefit from those improvements. Chen says the plan is for the work to take six to nine months while O’Callaghan (who addresses her as a "beautiful woman") puts the tenants up in a hotel.

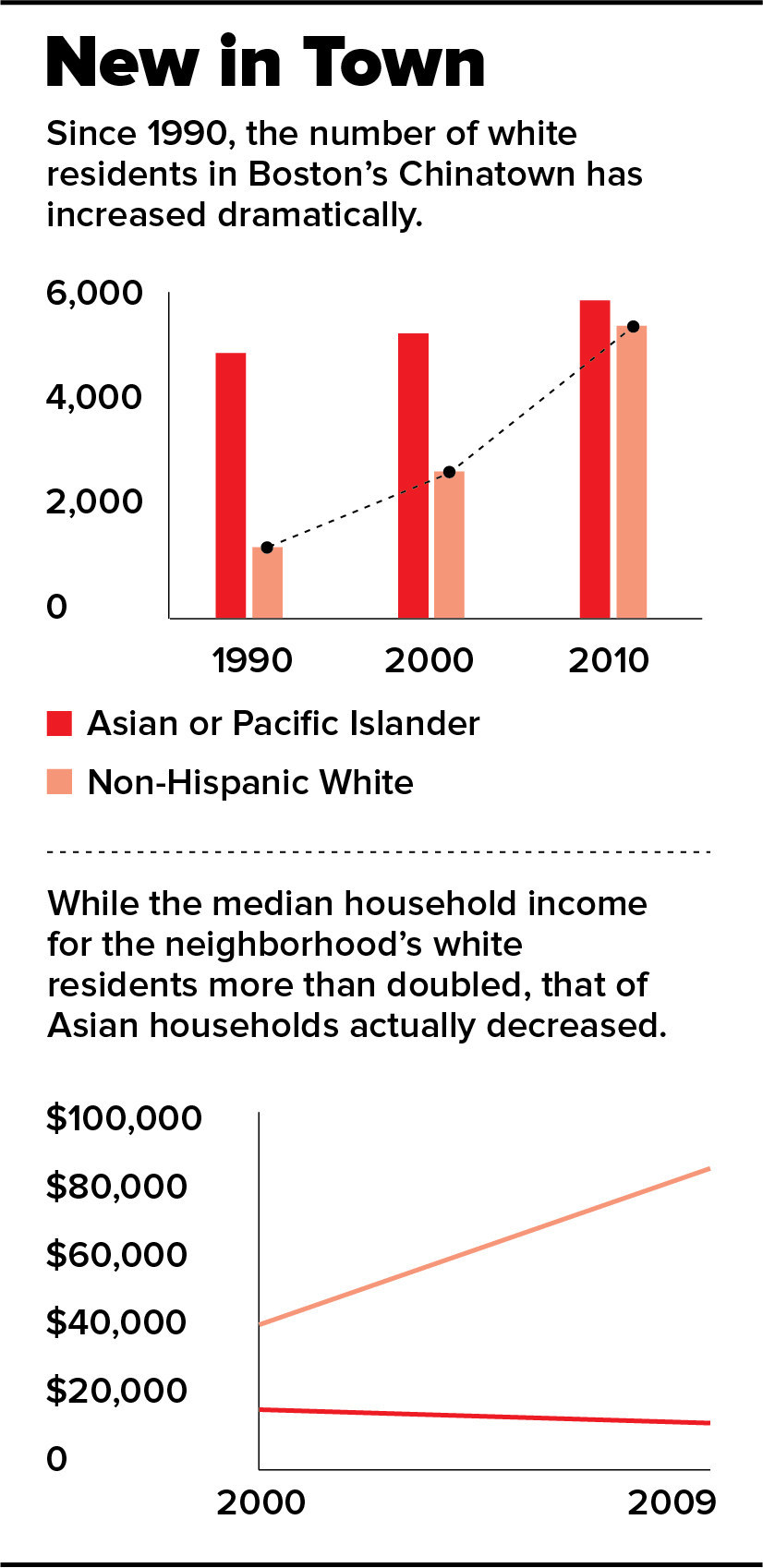

It’s a pattern becoming more and more familiar in the transitioning neighborhood. A 2013 report by the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (AALDEF) found that the absolute number of Asian residents in Boston’s Chinatown actually increased a little in recent decades, as tall apartment and condo buildings nearly doubled the neighborhood’s population. Yet the overall percentage of Asian residents in Boston's Chinatown fell from 70% to 46% between 1990 and 2010. And the economic discrepancies between the two groups are extreme: The typical Asian household in the neighborhood made $13,057 in 2009, while the typical white one made $84,255. When a new residential project across from the Yu’s building designated 95 affordable units, it received more than 4,000 applications.

And it isn’t just Boston. Gentrification is not a new reality in American cities, but it is reshaping the country’s Chinatowns at a rapid pace. In New York City’s, strong community organizations and ownership of buildings by Chinese associations have helped stem the loss of housing for immigrants, but local advocacy groups say displacement is still a looming threat; a recent Vocativ analysis found that Chinese-Americans in NYC’s Chinatown dropped from 55 to 49% between 2009 and 2014. The shift in Philadelphia’s Chinatown has been even more dramatic, dropping from 74 to 48% in that same period. In Washington, D.C.’s Chinatown, there are only 300 Chinese-American residents left, down from a peak of 3,000 in 1970. The area’s still a tourist destination with Chinese restaurants, and a city regulation means that all businesses in the area have Chinese signage — you can find a Hooters with a sign in English and Chinese characters. But the local Chinese grocery stores and bakeries have all shut down.

“That is our nightmare,” says Andrew Leong, an associate professor of law, social justice, and Asian American studies at University of Massachusetts, Boston, who co-authored the AALDEF study. “That’s our warning sign. That’s what we do not want our Chinatowns, our living communities, to turn into.”

As the rally continues, several members of the local press approach O'Callaghan and he declines comment. But then, as Pei Ying Yu takes the mic to tell her story, he suddenly interrupts to call to the reporters: "She can move back in the building. You can put that on record.” State law requires that tenants displaced for a building rehab be allowed to return, he says. (Which is sort of true: Were O’Callaghan to evict the tenants that day, they could have protested due to the building’s code violations. But no-fault evictions are legal in Massachusetts, so once the building is repaired, he’ll be within his rights to evict the tenants and raise rents.)

But O'Callaghan insists it isn't just a matter of following the law. "We're not looking to displace the people," he promises, as the tenants pack their belongings inside. "They're going to move back in. They're coming back. They're not going to get screwed."

The Yus’ apartment is part of a few blocks of row houses, dotted with produce stands and tiny grocery stores and wedged between Tufts hospital, a DoubleTree Hotel, and the I-90–I-93 interchange. Nearby, in the shadow of growing high-rise apartment buildings just a few blocks from Boston Common, is a cluster of hot pot and dumpling restaurants with bright red and yellow signs. There are a couple chain stores — a CVS, a Boston Pizza — but also social clubs where new immigrants get help translating paperwork and finding jobs. At the local public elementary school, students learn English and Mandarin and celebrate Chinese festivals.

Hemmed in by poverty and discrimination in the 1870s, Chinese immigrant workers settled in a neighborhood that was home to a series of impoverished immigrant groups: Syrians, Jews, Irish, and Italians. Riddled by railroad tracks and terminals, it was one of the worst places in the city to live. Chinese residents put up laundries and restaurants, building what would be a center of Asian-American life in New England for more than a century.

In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act barred most Chinese women and children from immigrating, leaving the neighborhood a little world made up almost entirely of men. So local leaders built a system of family associations: surrogate uncles and nephews and cousins bound together in mutual support by a common family name. That same exclusion helped give rise to organized crime; a 1974 city decision to locate a red-light district known as the Combat Zone right next door to Chinatown also stoked Bostonians’ concerns that it was a dangerous place to live. But those worries dissipated as crime fell throughout the city over the past two decades. Since 2005, dozens of neighborhood volunteers in blue vests have been patrolling the streets in the evenings, helping to keep illegal activity down.

Chuck Kwong, an upstairs neighbor of the Yus who’s around their age but has lived in Chinatown much longer, recalls the neighborhood as he found it when he first moved to Boston in the early '70s. He'd been able to rent an apartment with friends for $100 a month — worth it even though they spent very little time there. He'd work at restaurants on Cape Cod, staying in boarding houses owned by his employer. On his days off, he returned to the apartment and spent hours wandering through Chinatown, stopping at restaurants and bakeries and social clubs where locals played mahjong.

But the neighborhood was already starting to get squeezed. Between the 1950s and 1970s, state and local governments built roads through Chinatown, knocking down homes and businesses. Urban renewal projects razed apartment buildings and replaced them with hospital and medical school buildings. Then, with the turn of the new millennium, luxury condos and apartments sprang up. Today, Kwong says, the social clubs are still filled with old-timers, but for the most part, new immigrants who could use their support can't find anywhere to live in Chinatown.

From one perspective, what’s happening is just part of life in a dynamic, thriving city.

“It is natural and it needs to happen,” says Skip Schloming, executive director of the Small Property Owners Association, a Boston-area landlords’ group. “The neighborhood needs to adjust to what’s needed.”

Schloming says it’s common for old buildings with low rents to deteriorate because the owners don’t have money for proper repairs. A booming housing market means landlords have the incentive to make improvements, but only if they’re able to charge higher rents. If that means displacing lower-income tenants, Schloming argues, the city should provide relocation services, helping tenants to find apartments in more affordable neighborhoods where they can reconstitute their local communities.

To some extent, that kind of relocation of the community is already happening, with many Chinese immigrants now living in the Boston suburbs of Malden and Quincy. But Leong, the UMass professor, says these Chinese enclaves are too diffuse to replicate Chinatown.

It's something the Yus themselves had experienced prior to moving to Boston. They grew up together in China’s Guangdong province, but took different routes to America as middle-aged adults. Pei Ying's a tiny, gregarious woman who usually wears jeans, graying hair tied up in a practical bun. She was an accountant before she left Guangdong for Atlanta, where her grown son still lives. Yan Nong, the more shy of the two, headed to San Diego, a longtime destination for Chinese immigrants. Yet without cars, U.S. work experience, or strong English proficiency, both sisters struggled to adapt to life in cities without major Chinatowns.

Acquaintances insisted that things were different in Boston. When they arrived, they were thrilled to find streets densely packed with shops catering to Chinese tastes and a bus and subway system that let them travel independently to jobs. In the midst of the tight real estate market, it was their new network of friends in Chinatown that helped them find the apartment at 103 Hudson.

"You can take transportation everywhere," Pei Ying Yu says. "Lots of agencies in Chinatown can read over letters for you. It's very easy. There's a lot of places to learn English as well."

Beyond practical conveniences, she says, there’s a sense of comfort in Boston’s Chinatown that she and her sister hadn’t found in other American cities. She said that, if it weren’t for housing issues, she wouldn’t hesitate to recommend Boston to any Chinese immigrant.

“I would say to them that coming to Boston will be just like going home, because everything you find at home you can find here in Boston,” she says. “You don’t have a language barrier. You step out your door, you’re going to have access to Chinese people.”

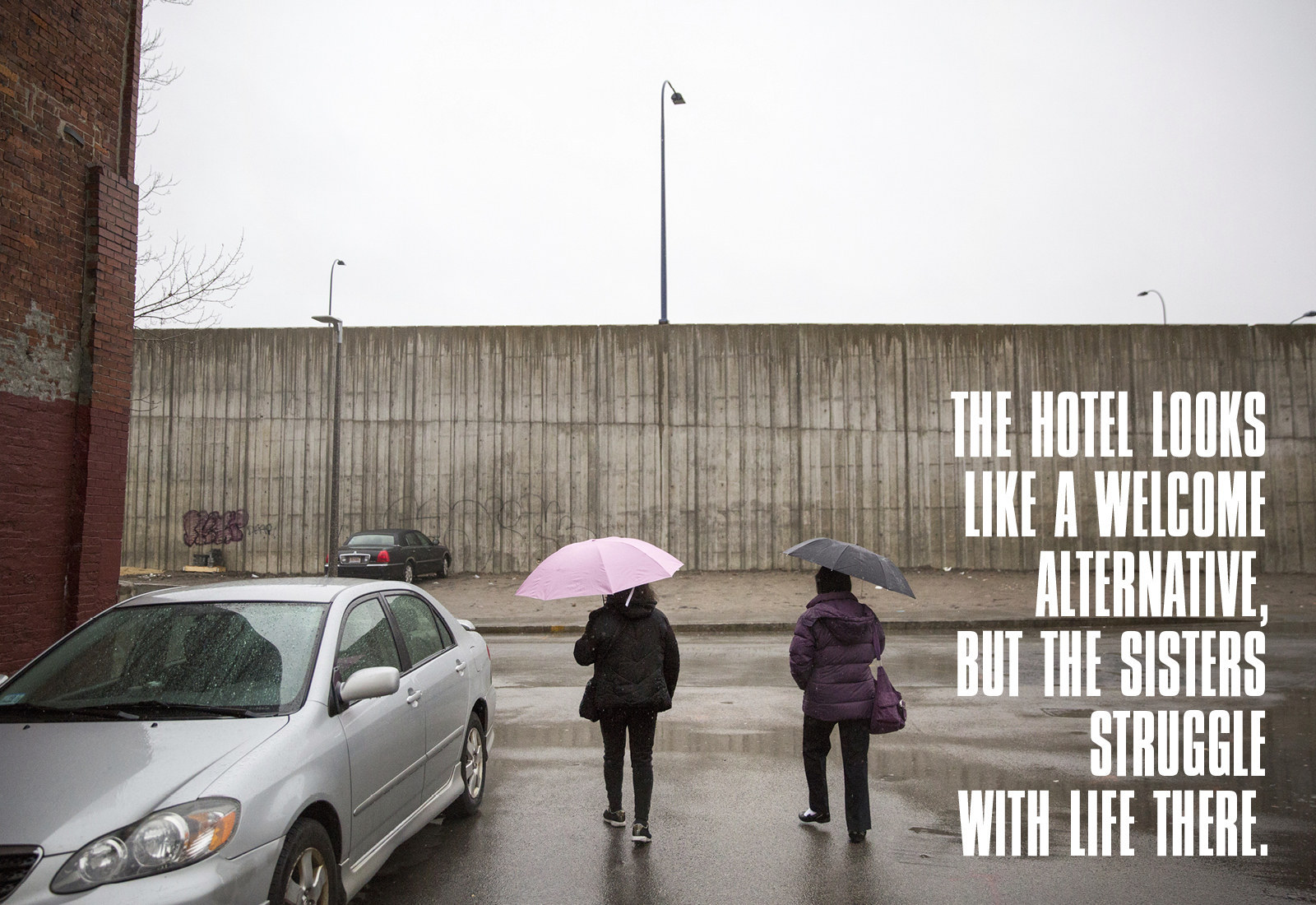

When the Yus leave their apartment that January day, they head to a no-frills hotel O’Callaghan arranged for them, about a mile and a half away from the old building.

From the outside, the hotel looks like a welcome alternative for the Yus — they aren’t homeless; they don’t have to pay rent — but privately, the sisters struggle with life there. To their dismay, it has no cooking facilities. The stores they know and neighbors who speak their language are a dozen blocks away. It takes them a week to figure out which buses they need to take to get to their jobs.

A few weeks later, just as they're beginning to get into a routine, O'Callaghan moves the tenants to another hotel, this time in the Boston suburb of Quincy. It's a gleaming Marriott high on a hill with a $16.95 breakfast buffet. For business travelers, this would be a nice upgrade, but the place is unsuitable for two older women with no car who speak very little English. Pei Ying’s commute requires her to take the hotel shuttle to the subway to the bus; since the first shuttle leaves at 7 and her job starts at 8:30, that means getting to work late. The organizers say they call O’Callaghan when more suitable places open up, like apartments with kitchens in Chinatown, but he doesn’t get back to them in time. They think this hotel might be a way to get tenants to give up on moving back to Hudson Street. O’Callaghan declined repeated requests for comment on why he selected the hotel and the CPA’s comments regarding it.

Most of the tenants find more convenient places to stay, for the moment at least — some quietly double or triple up with friends at their apartments, hoping the landlord doesn't notice or doesn't care. But the Yus don't have anywhere else to go. They stay at the shiny hotel.

Over the next few months, no work moves forward at 103 Hudson. O’Callaghan doesn’t even apply for building permits. The CPA urges him to make a deal, asking for a multi-year contract with the tenants that includes at least one year without raising the rent. They organize rallies, bringing out white-haired longtime Chinatown residents, young Chinese-American activists from neighboring towns, and supporters from other Boston housing rights groups.

The sisters, along with the rest of the Hudson Street tenants, become symbols of the danger Chinatown is in. Local media showed up the day the Yus moved out in January, and outlets continue to cover their situation. In April, the Boston Globe runs a feature on housing in Chinatown centered on Pei Ying.

The Yus, who’ve never been involved in any kind of activism before, take personal days from their jobs to show up at the rallies. They chant slogans and tell their stories, breaking down crying in front of TV cameras and crowds of strangers.

In early April, Pei Ying marches with dozens of supporters from her old apartment on Hudson Street to City Hall. She tells her story again, recalling the time she hopped on the Marriott shuttle to get to her subway stop and discovered too late it was actually headed to a shopping mall. She ended up stranded, late for work, and terrified of losing her job. Lately, she's taken to keeping a loaf of bread in the big red backpack she carries everywhere, in case she gets lost and can’t find anything else to eat.

"This heartless, heartless landlord, he has no idea what the tenants have to go through," she tells the crowd. "I just want a home. I just want a place to stay. I did not do anything wrong. I was a good tenant. I was working, trying to pay my rent. All I ask is that I can come back to my home, come back to Chinatown."

She insists none of this has soured her feelings about Americans. She keeps talking about how nice people have been to her, how many friends she'd make if she could just speak English better. She remembers one night when she was still adjusting to life at the first hotel. She got off the bus and couldn't find her way home. It was snowing hard, and the only people on the streets were an American couple. Somehow, she communicated where she needed to go.

"They both held one arm of mine and led me back to my hotel," she tells me. "It was so cold. The snow came up to our knees."

Through a translator, I ask what she'll do if she can't go back to her apartment. She says she doesn't know. "I don't have a next step," she says. "I am in desperation right now."

After cheering Pei Ying Yu and other speakers at the rally, the crowd of CPA supporters files into City Hall along with hundreds more people from all over Boston. A city councilor has called a hearing on housing affordability, and the council chamber is packed.

For the first two and a half hours of the hearing, city officials and nonprofit leaders talk big picture. Boston’s housing chief explains that the city has a plan to create 53,000 new units of housing. But only 1,700 of these are for people with very low incomes — up to $49,250 for a family of four. Leaders of local community development corporations talk about how they’ve been able to get affordable units built over the years — but nowhere near enough to fill the need in their neighborhoods. The head of the Fair Housing Center of Greater Boston says the city is facing a new sort of gentrification, driven largely by large institutional investors and developers jumping on an obvious chance to buy high and sell higher.

Then, at 6:40 p.m., they open the floor for public comment.

Dozens of people line up for their turn at the mic. There's an Italian-American woman who grew up in working-class South Boston, where locals identified themselves by which Catholic parish they were in — her mom was from Gate of Heaven, her dad from Saint Brigid. Now, she says, she’s been forced out by the cost of housing. All the new construction is luxury condos. “When did luxury become the standard?” she asks. “Luxury used to be a choice.”

Andres del Castillo, an earnest young community organizer from East Boston, talks about how his sisters volunteered in the neighborhood when he was growing up, helping to turn it from a high-crime area into a cultural center for Boston-area Latinos. But today, he and his two roommates can barely afford to pay their rent there, even though they’re young working guys with no kids to support.

Someone asks del Castillo to wrap up. Sixty-four people have signed up for the public comment period. At this rate the hearing could go on all night.

Del Castillo doesn’t surrender the mic immediately. "If our city isn't answering for its residents, I mean, what is it here for?" he asks. "Profit is not enough of a motive. Profit is not enough of a reason.”

This, by most standards, is a terribly naive thing to say. Schloming, the head of the Boston landlords’ group, says it’s easy to complain about greedy building owners, but the profit motive is what gets new housing built and old housing properly maintained. Limiting the rent landlords can charge, or making evictions more difficult, means development grinds to a halt. The nightmare case, Schloming continues, is landlords burning down their buildings for the insurance money because it’s impossible to make money on them.

If we really want to promote affordable housing, he explains, one solution is less regulation. Better zoning rules could promote a dense city full of pedestrians and bikes, allowing large apartments to be subdivided into smaller ones and removing requirements that buildings include spots to park cars.

“The city needs to be prepared to adjust to a new society,” Schloming says. “Boston needs to grow.”

There’s a counter-narrative, however, that groups like the Chinese Progressive Association are promoting. Coined by French philosopher Henri Lefebvre, "right to the city" is a school of civic thought that seeks to empower urban dwellers. In short, it means that a city is created by the people who live there, so they ought to run it. The phrase has been adopted by everyone from refugees in Germany to Turkish opponents of a shopping mall planned for a major city square to anti-foreclosure activists in New York, Atlanta, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Washington, D.C.

The CPA is part of a national organization called the Right to the City Alliance, which turns that notion into specific policy goals for the U.S. In a 2014 report, the alliance noted that 28% of U.S. renter households in 2011 spent more than half their income on rent. The alliance calls for some drastic measures, including rent control laws, construction of more public housing, and restrictions on the ability of investors to buy and sell housing for a profit.

One model that the Right to the City Alliance favors is the community land trust. The idea is a sort of land ownership cooperative that lets buildings be bought and sold while making sure they stay affordable. One such community-run housing model exists right here in Boston: the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative community land trust. When the housing market crashed, the land trust helped its members escape foreclosures. When home prices bounced back higher than ever, Dudley Street avoided price hikes and displacement. In the months before Tim O'Callaghan's company bought 103 Hudson St., the CPA had been trying to get the old owner to sell it to a newly formed Chinatown Community Land Trust, partly modeled after Dudley Street, but O’Callaghan put down a better offer on the building.

A couple of weeks after the City Hall hearing, I reach out to him again.

He picks up his cell phone, but the connection is bad, and he doesn't want to talk. He asks me to leave him alone. He doesn't hang up, though. He says he's figuring out how to do right by the tenants and negotiating with them over the leases — if they can get approved for federal Section 8 housing vouchers, he'll be able to move them back in once the rehab is complete.

It’s noble, but unfortunately unlikely. Only 1 in 4 Americans who qualify for vouchers get one. In Boston, the waitlist for Section 8 has 40,000 names on it, which translates to an 11-year wait.

O'Callaghan starts to sound aggrieved. He notes that he's putting the tenants up in the hotel for months. "They're living the American Dream," he says, "for free." Then he catches himself. "It's a very overwhelming process. I don't want to be negative about nobody."

It's 5:45 a.m. on May 1, three months after the Yus left Hudson Street, and Laurence Louie is walking down the stairs of his apartment just off the Boston College campus on the city’s western edge. Running on two hours of sleep, he’s off to pick up Pei Ying and Yan Nong at the Quincy Marriott and bring them to Chinatown.

Louie's been driving the Yus once or twice a week. He’s one of the volunteers the CPA has arranged to ferry the sisters to and from the hotel everyday. Dressed in a hoodie and a backward baseball cap, the 28-year-old grew up in working-class Boston suburbs, but Chinatown was always central to his family's life.

"It's the place we go every Sunday morning for dim sum," he tells me as we take off toward Quincy. "It was the place where my mom, who was a Chinese immigrant, could kind of be at home."

Louie's mother moved to America around age 20, where she became a history teacher at a bilingual Boston school and started a Chinese rock band out of a Chinatown studio. Louie joined the CPA’s youth program at 17 and later became the program's director. In 2013, he left Boston for a year in China. When he came back, he found himself spending more time with friends in Chinatown than in the suburb where he lived.

As we hurtle down the tangled Boston highways toward Quincy, Louie tells me he wants to stop and get something to eat. Otherwise, he knows from experience, Pei Ying Yu will try to buy him breakfast when they get to Chinatown. If she bought breakfast for everyone who drove her, she'd be completely broke, he says.

Bag of donuts in hand, we pull up in front of the Marriott around 6:30. The Yu sisters are at the revolving door. Pei Ying holds her heavy red backpack, which holds her lunch and bottled water. She's also taken to carrying her passport and important papers around with her; she doesn't feel safe leaving them anywhere. Her shoulder hurts.

As he drives, Louie translates for me as the Yus tell us about their recent transportation mishaps: ending up on subway lines going to the wrong destination or getting to their stop after 9 p.m., when the hotel shuttle stops running. They say they're so grateful to the volunteers who drive them to and from the hotel. They talk about feeling guilty when they don't have the money to tip hotel maids or shuttle bus drivers. They say not being able to cook means eating expensive, unhealthy meals — often cold sandwiches or pastries that they pick up when they manage to get to Chinatown — but they don't see another option.

"There's kind of this anxiousness that she has every day now being away from the home,” Louie says, translating for Pei Ying. “Not knowing moment to moment where you can be and what you can trust and what you can't trust.”

Yan Nong mostly stays quiet. But then we get to talking about the landlord. Suddenly she speaks up, fast and adamant.

"Why in the U.S., and why in America, why is there this kind of discrimination and exploitation of Chinese working-class immigrants?" Louie translates. "And why can't the U.S. system do anything about this? Why do we have to live through this?"

We arrive at Chinatown around 7. Yan Nong works around here, but Pei Ying still has to catch a bus to her job outside Boston. Louie navigates small streets clogged with delivery trucks bringing food to the restaurants and corner stores.

After she gets out of the car, Pei Ying heads straight to a bakery and buys a number of pastries and sandwiches. As I take photos, she points to various items, and, after a while, I understand she wants to buy me something. I shake my head and say no repeatedly, but she buys a sandwich for me anyway, a sort of club with lettuce, ham, and pressed tofu.

As she leaves the bakery, she runs into someone she knows from the neighborhood and they chat briefly in Chinese. But she's in a hurry, so she resumes walking the few blocks left to the bus stop. She says goodbye to me by pressing her hand to her heart.

A couple weeks later, on May 12, O'Callaghan, a representative from the city building department, a couple of CPA staffers, and five of the Hudson Street tenants meet in Boston Housing Court. The city is still contemplating taking over the building, considering the extent of its issues and the lack of action on the developer’s part so far. The Yus, who've taken another personal day from their jobs, are both dressed up. Yan Nong — fresh off a protest where she and other displaced tenants built a symbolic tent city — wears asymmetrical earrings and a striped blouse. Pei Ying is visibly exhausted, having trouble keeping her eyes open as the judge and lawyers talk.

The city’s case over the potential takeover of the building will not move forward today, because the whole situation has suddenly changed. O'Callaghan's company has finally filed for a permit, and it’s not to spend a few months refurbishing the building and bringing it up to code. He wants to gut the whole thing, combine it with a neighboring building that the company also bought, and build additions, turning the combined property from eight apartments into 10.

This means two things: First, if the permit goes through, there’s very little chance of a city takeover of the building. And second, it will be a long time before any tenant — old or new — lives at the building again.

Months pass with the Yus camped out in Quincy, still not paying rent but still in housing limbo. The CPA organizers look for ways to stop O’Callaghan’s plans as they wind their way through the city’s permitting process, without success. Ultimately, there’s just not much the city can do about the things a landowner wants to do with his own property.

The city comes to Pei Ying Yu’s aid in a different way. Because she’s over 60, she qualifies for senior housing, which has a much shorter waitlist than other subsidized housing in the city. At the end of August, she reaches the top of the list and gets a place in a building in Boston’s South End, on the other side of I-90 from Chinatown. She isn’t crazy about the location; during the day, it’s a 20-minute bus ride to buy groceries in her old neighborhood, and at night — when buses don’t run as frequently — she finds herself walking through unfamiliar streets. But at least she has a kitchen again.

The next time I see Pei Ying, in November, she’s visibly more relaxed than she’s been before. We meet at the CPA headquarters, commandeering an office where we can speak privately. Speaking through a translator, she tells me she’s able to cook for herself at her new place, which is a huge relief, even if she still has to take a bus into Chinatown to do her grocery shopping. Yu spends a lot of her time in Chinatown for other reasons, too. Through CPA, she’s become active in the Fight for $15 living wage campaign. She was recently elected to the steering board of the neighborhood’s highly active residents’ association.

“Being on the steering committee gives you a voice,” she says. “It allows me to vocalize my needs and then be able to advocate for them. Also you get a lot of information if you want to participate in the different activities in the community.”

She says becoming an activist has changed her. “It’s really great spiritual nurturing for me,” she says. “I feel much more alive.”

In December, O’Callaghan’s company received its permit for reconstruction of the Hudson Street building, but very little work seems to have moved forward over the winter. The city’s Inspectional Services Department found 101 Hudson uninhabitable, so on March 4, 2016, the four tenants living there were forced to move out. Chen says they’re now staying with family or couch-surfing.

With the help of their legal aid lawyer, the Yus are pursuing two civil cases against O’Callaghan and his company, arguing, among other things, that while they were still living in their apartment he barged into their unit, intimidated them, and discriminated against them by refusing to let them use Chinese Progressive Association staff as translators. O’Callaghan, First Suffolk, and their lawyer did not respond to multiple requests for comment regarding plans for the buildings, the future of tenants there, and the civil cases.

As of March 10, Yan Nong is still living at the hotel, but the CPA’s Karen Chen says she spends many nights at friends’ homes to ease her commute.

Meanwhile, the CPA, together with a coalition of other Boston tenants’ groups, is pushing for broader change, including an end to no-fault evictions and a new long-term city development plan that prioritizes housing for people of all income levels. They’ve had some success convincing Boston Mayor Marty Walsh to come out in favor of just-cause evictions, but there’s still a long way to go.

After her whirlwind year, Pei Ying Yu wants to stick out that fight.

“Chinatown has 150 years of history,” she says. “As Chinese people, we have the obligation to protect this history. We want Chinatown to glow.” ●

UPDATE

This story has been updated to clarify the demographics of South Boston.