Although Klansmen outnumbered Klanswomen by 6 to 1, at least half a million women (some claimed as many as 3 million) joined the movement, and that doesn’t count the many who participated in its public events and supported its ideas. In fact, women clamored to participate from the moment the second Klan reappeared. They contributed a new argument for the cause: that women’s emergence as active citizens would help purify the country. That claim may well have emerged only after the women's suffrage amendment was ratified in 1920; before that, many Klanspeople of both sexes probably had doubts about the righteousness of women entering politics. Nevertheless, the claim that women might bring “family values” back into the nation’s governance — a claim made at the time in movements of all political hues — created a contradiction within conservative movements: Despite an ideological commitment to Victorian gender norms, including women’s domesticity, many conservative women enjoyed participating in politics. In fact, some Klanswomen interpreted political activism as a female responsibility. Then, once active, they often came to resent men’s attempts to control them and even challenged men’s power. Thus we meet a phenomenon that many progressive feminists found and still find anomalous — the existence not only of conservative feminism but even of bigoted feminism. Readers who have not already done so must rid themselves of notions that women’s politics are always kinder, gentler, and less racist than men’s.

Readers who have not already done so must rid themselves of notions that women’s politics are always kinder, gentler, and less racist than men’s.

Women who became active in the Klan were continuing a populist tradition of the 1880s and 1890s. Even without voting rights, women had constituted a significant force in the Farmers Alliance and then in the Populist and Socialist Parties. Women activists spoke at meetings, edited newspapers, lobbied legislatures, published novels, wrote political tracts, ran for local offices, and got elected to leadership in the Alliance — in short, they engaged in every form of political activity allowed to them. When the Populist Party emerged, women were increasingly shut out of official roles, not only because of their disenfranchisement but also because increasing Populist power made male leaders less open to sharing influence. (It was often the case that women had more space to lead in social movements than in formal political parties.) There were exceptions, though. Kansas feminist Mary Elizabeth Lease, to cite just one example, was a major Populist traveling speaker, in demand throughout the Midwest. She gave the opening address at the 1892 Kansas Populist convention and was an at-large delegate at the national convention. Many Populist women were also stalwarts of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. They brought these experiences into the Ku Klux Klan. They did not assume that politics was a male activity.

Moreover, women had won at least partial suffrage in 27 states and the Alaska Territory prior to the national amendment, and these states included those where the Klan was strong, such as Indiana, Iowa, Nebraska, and Oregon. But the 1920s political world into which Klanswomen entered was rapidly changing. After the 19th Amendment was ratified, the most visible women’s rights organizations waned in strength. As a result, the narrative of women’s struggle for equality has often characterized the 1920s as a period of inaction or even retreat. But that conclusion, while accurate with respect to electoral engagement, does not hold up with respect to social and cultural developments. For example, rates of women’s college education mushroomed. Between 1910 and 1920 the number of women in college doubled, reaching almost 300,000, or nearly half of all students in higher education. That increase continued during the Klan’s heyday, growing by 84% through the 1920s. Similarly with women’s employment: By 1920 women constituted 21% of all those employed outside their homes, a rate much higher among poor women and women of color, of course. Both changes — education and employment — drew more women into the public sphere; even those with husbands who could support a whole family were spending more time outside their homes. Progressive Era women activists had obtained a base for promoting women’s and children’s health and welfare in the US Children’s Bureau. At the same time, divorce rates were growing, which meant that more women were not only leaving husbands but also fighting for child custody, always the right about which women cared most.

Meanwhile, commercial culture was responding to these changes. The stereotype of the new culture had been the flapper, but this was a small group compared to the millions captivated by new forms of leisure and social adventure, many of them entirely secular. Prohibition was flouted openly in big cities and discreetly in smaller locations. Advertising morphed from information about where particular commodities could be purchased to imagery that persuaded people that they needed new products. Nightclubs, records, and above all radios brought jazz out of Harlem into white communities. Radio broadcasting began in 1920; by 1930, 60% of Americans owned a radio, and as a result radically expanded the acquaintance of small-town and urban Americans with big-city culture. By 1927 50 million Ford cars were on the roads — many with women drivers — offering greater mobility and privacy. Well into the 1960s, most young people had their first sexual experience in a car. For the young and unmarried, unchaperoned commercial leisure such as dance halls, soda fountains, and the movies — where couples could sit in the dark! — became a magnetic attraction. Images of beauty changed rapidly: Women cut off and “bobbed” their hair (using, significantly, a male name to describe the new haircuts), and wore makeup, shorter skirts, and brighter colors.

Together these cultural developments transformed social life and, of course, created a backlash. Conservatives railed at the decline of morals, and by this they meant mainly women’s morals. Walter Lippmann’s phrase “the acids of modernity” captured Klannish fears that the very ground of Protestant morality was being eroded. The Klan blamed Jews and, to a lesser extent, Catholics for subverting what would later be called the gender order; nevertheless, Klanspeople fretted about immodesty precisely because this freer social and sexual culture appealed to Protestants as well. Because anxiety about immodesty focused on women, Klanswomen were both repelled and enticed by these developments, and this shows in the contradictions within their program and activism.

Klanswomen were often wives of Klansmen, but many joined on their own, and others led their husbands into the organization.

Klanswomen were often wives of Klansmen, but many joined on their own, and others led their husbands into the organization. In fact, some husbands resented their wives’ Klan activities and absences from home, and some opponents taunted Klansmen with the charge that they were not man enough to keep their wives at home. It seems likely, though, that Klanswomen often spent more hours on Klan work than did rank-and-file Klansmen because they had more disposable time.

Women did not always wait to get Klansmen’s permission to join the movement but organized themselves independently through churches, clubs, sororities, and Klan picnics. Male leaders, alarmed by these initiatives outside their control, formed competing women’s groups, producing a variety of organizations with names such as Kamelias, Queens of the Golden Mask, and Ladies of the Invisible Empire. In 1923 Imperial Wizard Hiram Evans, seeing that women could not be kept out of the Klan movement, managed to merge these groups forcibly into the Women of the Ku Klux Klan (WKKK). Some preexisting women’s groups resisted this merger, and then, after acceding, refused to accept a subordinate status. An Oregon group proclaimed that “the women’s organization is an exact counterpart of the Klan itself, with no difference whatever except that of gender. They will use the same constitution, ritual, regalia, and methods.” In another assertion of its independence the WKKK set up its headquarters in Little Rock, hundreds of miles from Atlanta, home of the Klan headquarters. By November 1923, the WKKK claimed chapters in all 48 states. In Indiana, the state of greatest Klan strength, where the population was 97% white and Protestant, the WKKK boasted of 250,000 members; if true (not likely), this would have meant that 32% of the state’s native-born white Protestant women belonged.

Brief profiles of three WKKK leaders illustrate their combination of conservatism with assertiveness, a combination that many might find surprising. Elizabeth Tyler, cohead of the Klan’s PR firm, defied almost all the gender norms of the time and displayed a business acumen that might befit a CEO today. Her career grew from both nativist and fraternal traditions. Born in 1881, married at 14, either abandoned or widowed at 15, she made several further brief marriages, becoming a multiple divorcée. In Atlanta in the 1910s she was a member of a sororal order, Daughters of America, an anti-immigration organization associated with the American Protective Association and many fraternal orders. Tyler participated in the eugenics cause as a volunteer “hygiene” worker, managing publicity and organizing parades for a “Better Babies” campaign. Through that activity she met Edward Clarke. Together they sensed the profitable opportunities that could arise from professionalizing and commercializing their efforts and set up the Southern Publicity Association, selling their services to groups like the Red Cross and the Anti-Saloon League. In their first 15 months of work for the Klan, they claimed to have netted upward of $200,000 ($2.7 million in 2016); this is probably an exaggeration, but they were doing well. Tyler personally owned and profited from the Searchlight, a Klan newspaper, and built herself a large Classical Revival house on 14 acres in downtown Atlanta. It was she and Clarke who turned [founder of the second KKK] Colonel Simmons’ feeble attempt to revive a southern organization into a mass national movement and a profitable business. When she turned her energies to creating an early women’s division of the Klan, she took advantage of Simmons’ temporary absence to put Clarke in titular control of the entire Invisible Empire. In 1919 their position became precarious when Atlanta police literally rousted them out of bed and arrested them for disorderly conduct; the “disorder” was the fact that they were sexual partners while married to other people. When the arrest was discovered two years later, newspaper coverage revealed not only the illicit sex but also that they had used false names and had been in possession of whiskey. The scandal was big news, covered even in the New York Times when the New Jersey Klan demanded firing Clarke and Tyler. Learning of the arrest some Klansmen were doubly dismayed — by the alleged immorality but also by the discovery that a woman was a key organizer of the KKK. One vilified her, adding that her experience “in catering to [men’s] appetites and vices had given her an insight into their frailties.”

Meanwhile, Klan opponents forced congressional hearings on the Klan in 1921. Fearing further exposure, since he was guilty of other improprieties, Clarke immediately announced his resignation. This made Tyler furious. She publicly denounced him, saying he was “weak-kneed and won’t stand by his guns.” She refused to resign. She even survived an attempt on her life when unknown assailants shot up her home. The congressional report treated her with both respect and misogyny, as the éminence grise behind the Klan. Instead of backing down, she skillfully turned the negative publicity from the hearings into a successful membership drive that grew the Klan exponentially.

The organization might well have grown without this driven, bold, corrupt, and precociously entrepreneurial woman, but it would likely have been smaller.

Tyler was finally forced to resign by accusations, almost certainly true, of embezzling Klan money. But she had been a gift to the national Klan. The organization might well have grown without this driven, bold, corrupt, and precociously entrepreneurial woman, but it would likely have been smaller.

While Tyler’s audacity might seem surprising in a

woman of the 1920s, the career of Daisy Douglas Barr undoes today’s assumptions even more, because she was a Quaker. In the late 20th

century Quakers became associated with liberal theology, anti-racism, and other progressive attitudes. But a century ago the Friends church included plenty of racists and conservatives and was moving rapidly toward Evangelicalism.

Barr was by no means the only Quaker in the Klan; in the town of Richmond, Indiana, for example, some 7% of Klansmen were Quaker.

A native Hoosier, Daisy Douglas Brushwiller was born in 1875 into a devout Quaker family. She was only 4, she later said, when she first felt inspired to testify to her spiritual commitment, and at 8 and again at 12 she felt “the personal call from God” to preach and spread the word. At 16 — her autobiographical narrative placed these experiences, conveniently, every four years — she reportedly preached her first public sermon, after which she was “saved” at a United Brethren service conducted by a woman evangelist. (“Girl evangelists” were in vogue at the time.) At 18 she married schoolteacher Thomas Barr, who joined the Klan at her urging and began leading tent revivals around the state. In 1910 she became pastor of the Muncie, Indiana, Quaker meeting. (Female ministers were uncommon in mainstream white Protestantism but by no means entirely absent.) Soon she too was preaching at revivals, causing many of her listeners to be “saved” and at least one sick man to be cured. She was prolific on paper as well as out loud, writing a great deal of poetry like this:

I am clothed with wisdom’s mantle ... I am strong beyond my years;

My hand typifies strength,

And although untrained in cunning Its movements mark the quaking Of the enemies of my country.

My eye, though covered, is all-seeing;

It penetrates the dark recesses of law violation, Treason, political corruption and injustice,

Causing these cowardly culprits to bare their unholy faces ... My feet are swift to carry the strength of my hand

And the penetrations of my all-seeing eye. My nature is serious, righteous and just, And tempered with the love of Christ.

My purpose is noble, far-reaching and age-lasting ... I am the Spirit of Righteousness.

They call me the Ku Klux Klan.

I am more than the uncouth robe and hood With which I am clothed.

YEA, I AM THE SOUL OF AMERICA.

Like many other clubwomen of the time, Daisy Barr was a joiner, never limiting herself to a single affiliation. A woman of formidable energy, she also threw herself into an array of reform causes: president of the Indiana Humane Society, active in the campaign for Prohibition, creator of the Muncie YWCA (the Y’s were then fierce temperance and revivalist organizations), and founder of a “refuge,” the Friendly Inn, for former prostitutes. (Like many such reformers, she was baffled that the “fallen women” were not interested in being “rescued” by evangelicals.) When the Barrs moved to Indianapolis in 1917, Daisy became president of Indiana War Mothers. Soon after the women's suffrage amendment passed, she became the vice chair of the Republican State Committee, the first woman to hold such a position; the male co-chair joined the Klan, quite possibly, considering her charisma, at her urging. Meanwhile, her husband became Indiana’s deputy state bank commissioner. This was a power couple.

Barr soon became Imperial Empress of a women’s Klan affiliate, Queens of the Golden Mask. She wielded considerable bargaining power with Klansmen, a power enlarged when she established the “poison squad,” a statewide women’s network (of which more below). The squad practiced black psywar, spreading rumors, allegedly from Catholics or Jews, designed to make the alleged sources appear immoral and thus to build support for Klan political candidates. By 1923 she was head of the Indiana WKKK and a traveling speaker for the Klan itself. A whirlwind of energy, in July of that year she led a naturalization ceremony with 200 women and claimed that 1,000 would-be members were present but lacked the proper regalia required for admission. Three months later she led Indiana’s most spectacular Klan parade yet. So influential was the Indiana WKKK under her leadership that she almost succeeded in moving its national headquarters to Indianapolis.

As WKKK spokeswoman, Barr frequently broadcast feminist messages. Her reform work had long been oriented toward women, and she campaigned to have a woman added to the Indianapolis police force — a typical Progressive Era cause, motivated by the belief that women were less corrupt and harder on moral offenses than men. She once publicly reprimanded a police officer for uncouth remarks. Her speeches honored women's suffrage and urged women to make active use of their new political citizenship. Her temperance arguments featured stories of drunken male brutality, as befitted a member of the WCTU. She hurled vitriol against gamblers, adulterers, and men who patronized prostitutes and despoiled young girls. She called on women to support female candidates, to step up and exert power in their churches.

Her affiliations arose, no doubt, from firm principle, but they were also lucrative. She contracted with the Klan to be chief WKKK recruiter for Indiana, Kentucky, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, New Jersey, and Minnesota. The agreement guaranteed her a dollar for each woman initiated and $4 for each recruit within Indiana. Moreover, she became the conduit for purchases of robes, from which she likely received a percentage of sales. (No wonder she refused to “naturalize” women who lacked the regalia.) But like Tyler, Barr was apparently not satisfied with these profits, and Klan leaders complained that she did not deliver the required sums to national headquarters. Numerous male Klan leaders did the same; the flow of money, combined with lack of accountability, presented irresistible temptations to corruption.

Klan feminism also appeared prominently in the work and words of the Rev. Alma Bridwell White. Although never an official of a Klan group, she was easily as influential as Barr in spreading its message. As evangelist, minister, and bishop, she founded the Pillar of Fire “holiness” congregations, gained national fame through multitudinous lectures, and wrote 35 religious books and some 200 hymns. Her Pillar of Fire religious movement ultimately established 52 churches, not counting a few abroad, 7 divinity schools, 2 radio stations, 10 magazines and newsletters, and 2 colleges. Like Tyler and Barr, she displayed extraordinary entrepreneurial skills, but her bigotry surpassed theirs and rivaled that of any Klansman in its intensity.

Born in 1862 in Kentucky, one of seven sisters, White was also a girl evangelist. She found rebirth at age 16 at a Wesleyan Methodist revival where, she later wrote, “some were so convicted that they left the room and threw up their suppers, and staggered back into the house as pale as death.” She enrolled in Millersburg Female College, then at age 19 traveled on her own to Montana and Utah, where she taught school — clearly an adventurous teenager. She married Kent White, a seminarian, and the couple started an unsanctioned Methodist Pentecostal church in Denver. They soon broke with Pentecostalism and moved their church into the holiness movement, christening it Pillar of Fire. Already impatient with her husband, Alma White took over and soon became its recognized leader.

In writing and performing, she not only surpassed the fervor of Klan lecturers but even claimed that many biblical heroes were actually Klansmen.

Defying protests from the Methodist hierarchy, White remained committed to arousing Pentecostal-style “enthusiastic” worship, with singing, shouting, dancing, and fits. Time magazine wrote that she generated “fundamentalist ecstasy and hallelujah-shouting.” Never particularly modest, she claimed the power to bring people to their knees, sobbing in an agony of contrition, or to “make them skip about the aisles, singing and shouting with joy.” As she described her method, she never prepared a sermon but chose a text and then waited for the “heavenly dynamite” to explode. Many Klan lecturers worked to induce a religious commitment among listeners, and many claimed biblical authorization for the Ku Klux Klan, but none as diligently as White. In writing and performing, she not only surpassed the fervor of Klan lecturers but even claimed that many biblical heroes were actually Klansmen. One of her many books, The Klan in Prophecy, reported that the KKK had been divinely ordained.

In 1907 one of the Whites’ converts, a rich widow, gifted them a large farm property in central New Jersey. The Whites moved there, naming it Zarephath, after the biblical village where the prophet Elijah raised the son of a widow from the dead. In 1918 White arranged for the evangelist who had converted her to consecrate her as Pillar of Fire’s bishop — the first woman bishop in the United States. She traveled the country speaking at revivals and camp meetings and established a mission in London, preaching against liquor and “present tendencies in women’s dress.” Her stamina and ambition outdid even the most committed Klan speakers; she claimed to have crossed the Atlantic 58 times and traveled 50,000 miles in one year.

Zarephath flourished and expanded. Alma White was part of a trend: the 1920s produced

numerous female preachers, particularly Pentecostal preachers, many of whom could arouse zealous followers through their tent revivals. Even a few more mainstream religious groups, such as Reform Jews, Northern Baptists, and Presbyterians, were giving women larger roles, and the Methodist Episcopals decided in 1920 to allow women deacons. (African-American churches had female ministers much earlier.) In starting a new church, Alma White was following the example of Mary Baker Eddy, founder of Christian Science, although she labeled Eddy satanic. White compared herself favorably to Aimee Semple McPherson, the most popular evangelist of the time, who advertised her 10,000-member congregation as the largest in the world. White emulated McPherson in establishing a radio station, WAWZ, the letters standing for Alma White Zarephath. (In 1961 Pillar of Fire established station WAKW in Cincinnati, the letters referring to her son, Arthur Kent White.)

Pillar of Fire distinguished itself from other holiness groups through its explicit and intensive support of the Ku Klux Klan. White’s writings and speeches focused on four pillars of Klan ideology: white supremacy, anti-Catholicism, anti-Semitism, and temperance. Perhaps because of her base in New Jersey, home of 117,000 African-Americans in 1920, she emphasized racism against African-Americans, while Klanspeople in locations with smaller black populations emphasized immigrants, Catholics, and Jews: “Social and political equality would plunge the world into an Inferno as black as the regions of night.” Noah cursed Ham, the black man, she reported, and ordered that he must be the servant of Japheth. “Whatever wrong may have been perpetrated against the Negro race by bringing black men to this country ... the argument will not hold that they should share equal social or political rights with the white men — the sons of Japheth.” She advocated, therefore, repeal of the 15th Amendment. “America is a white man’s country and should be governed by white men. Yet the Klan is not anti-negro ... [but] is eternally opposed to the mixing of the white and colored races... God drew the color line and man should so let it remain.” “Red men” were equally doomed because God had given the land to the sons of Japheth.

“America is a white man’s country and should be governed by white men. Yet the Klan is not anti-negro ... [but] is eternally opposed to the mixing of the white and colored races."

Her camp meetings and revivals began to feature cross-burnings and Klan lecturers. She published three books of praise for the Klan and a periodical devoted exclusively to the Klan, the Good Citizen, and offered positive appraisals of the Klan in her many other sermons, books, and hymnals. The Klan funded her purchase of Westminster College (later renamed Belleview College) in Westminster, Colorado, a dilapidated former Presbyterian school; located high on a hill, it proved a perfect location for cross-burnings that were visible for miles. She established there another Christian radio station, KPOF, known as AM91: The Point of Faith. Three years later the Klan provided the funds to establish Alma White College in Zarephath, used frequently for Klan meetings and large spectacles. In 1926 the Klan joined White in establishing a 396-acre summer resort for its members in Zarephath.

Alma White anointed the Klan as the country’s savior: “Now come the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in this crucial hour to contend for the faith of our fathers. ... There is no longer any excuse for those who, like Elisha’s servant, have been blinded by the falsehoods propagated by the enemies of the Klan. ... The Klan is a tree of God’s own planting.” She also situated the Klan in a historical patriotism: “Our heroes in the white robes are the perpetuators of the work so nobly begun by the colonists and the Revolutionary fathers.” She supported the Klan’s electoral activism: “They must name candidates who can be safely trusted, those who will not betray the public on questions of such vital importance as prohibition, restricted immigration, white supremacy and other issues.” She also called for “the prevention of unwarranted strikes by foreign labor agitators.”

At the same time, White made no attempt to soft-pedal her feminism. She reprinted the 1848 “Declaration of Sentiments” from the famous Seneca Falls women’s rights convention in one of her books. She condemned women’s lack of legal rights vis-à-vis their husbands, calling for action against wife-beating and for women’s right to their own property and legal domicile. (In many states a husband could still control his wife’s property and require her to move with him anywhere he desired.) She called for sex equality in inheritance rights. Defying evangelical opposition to divorce, she argued for a woman’s entitlement to divorce in case of infidelity or threat to her personal safety. She denounced the practice of granting child custody to men in divorce — important because the risk of losing children was by far the most important factor keeping women in abusive marriages. And she supported the Equal Rights Amendment, first proposed in 1923 (and, of course, still not ratified).

This passionate feminism likely arose, in part, from her own ambition and a bitterness about the obstacles and insults she had encountered. But her brand of feminism also supported her religious bigotry. The Catholic Church rested on the subjugation of women, she charged. This accounted for its opposition to Prohibition: Liquor was for Catholic men a tool for keeping women subordinated. Convents were “paper prisons” that served to keep women uneducated, in ignorance of cultural and political affairs; they continued the “Old Roman law which made women the chattels or the slaves of men.” The church “hates any movement that tends to the uplifting and enlightenment of the tender sex.”

Each in her own way, Elizabeth Tyler, Daisy Barr, and Alma White rupture some commonsense expectations about the 1920s Klan and other conservative movements. Perhaps most striking was their entrepreneurship, which involved both ambition and skill, both principle and profit. In this respect, they probably differed from rank-and-file Klanswomen. Experienced at organizing large events, state-of-the-art in managing money, unafraid to attract publicity, they were thoroughly modern women. Nor did they disguise their work in sentimental, Victorian versions of femininity. Tyler’s life itself challenged the sexual double standard; Barr and White, while properly married, rejected female domesticity. But their outlook on the world may not have differed so much from that of their followers and of hundreds of thousands, at least, of other Klanswomen. In this movement, as in liberal and leftist movements, women found themselves enjoying not only the sociability and prestige of club membership but also the opportunity to weigh in on political matters. The clubby solidarity of the WKKK, like that of the Klan itself, grew more attractive, more interesting, when it involved collective action.

Barr and White were also women’s rights advocates, as was Tyler, implicitly, through her achievements. Their activism requires a more capacious understanding of feminism. Their combination of feminism and bigotry may be disturbing to today’s feminists, but it is important to feminism’s history. There is nothing about a generic commitment to sex equality that inevitably includes commitment to equalities across racial, ethnic, religious, or class lines. In fact, espousing sex equality and enacting female leadership have often been easier for conservative women, because their whole ideological package does not threaten those who benefit from other inequalities. (Leaders such as Margaret Thatcher and Sarah Palin may serve as illustrations.)

There is nothing about a generic commitment to sex equality that inevitably includes commitment to equalities across racial, ethnic, religious, or class lines.

Barr’s and White’s fusion of religion and politics also suggests another way that Klanswomen fit into the American political tradition. That tradition may have been weakening among urban elites, but it remained strong in the Midwest and West and in smaller cities. Bringing religious passion to politics was not only an instrumental combination, though it was that. The women’s mastery of public speaking, derived from church experience, not only benefited the Klan but also brought them personal rewards — fame, prosperity, and the pleasure of doing something so well and so highly valued. We should not assume that the late 20th-century rise of the Christian Right was unprecedented. ●

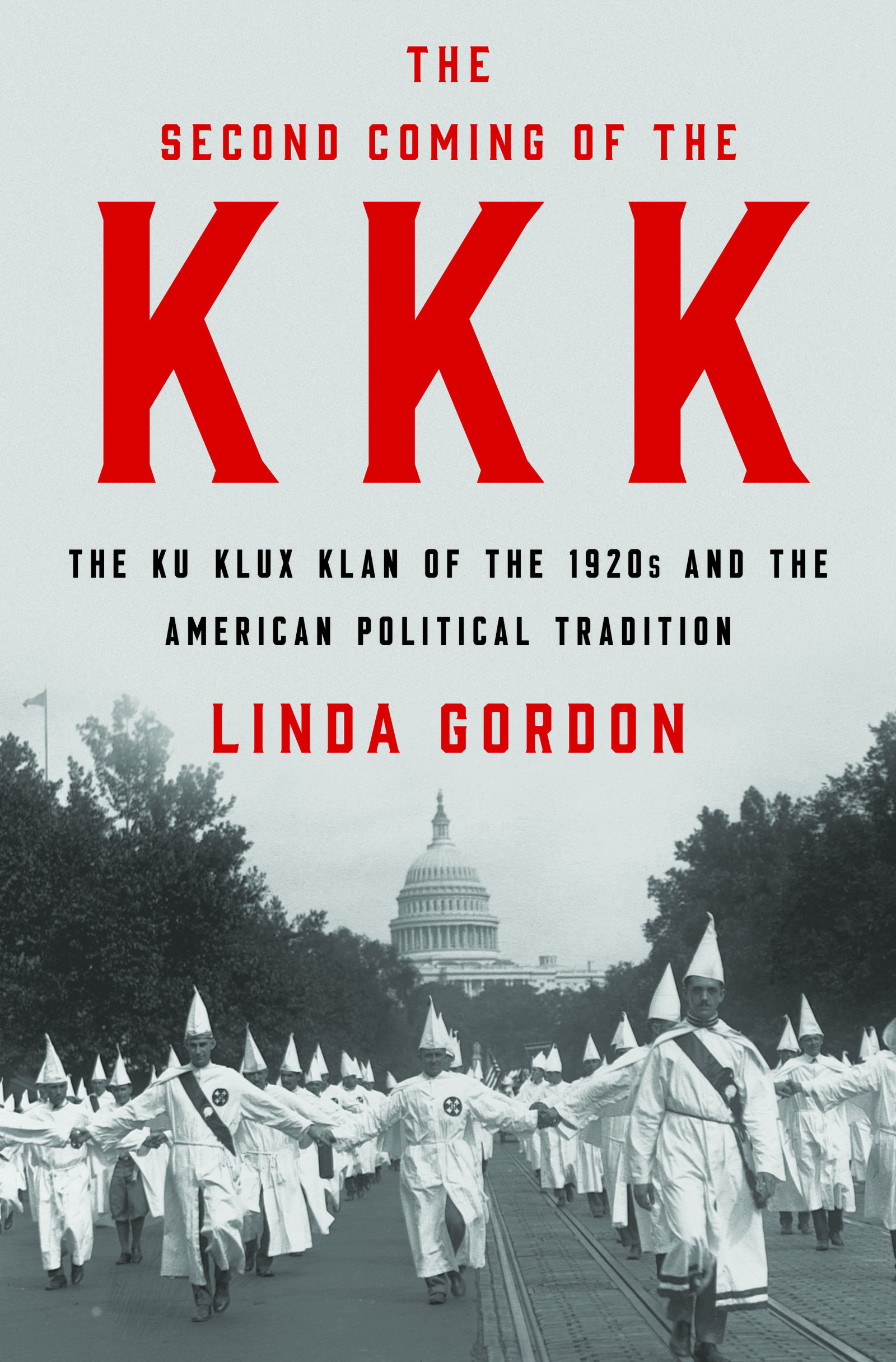

Excerpted from The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition by Linda Gordon. Copyright © 2017 by Linda Gordon. With permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company. All rights reserved.

Linda Gordon, winner of two Bancroft Prizes and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, is the author of The Second Coming of the KKK, Dorothea Lange and Impounded, and the coauthor of Feminism Unfinished. She is the Florence Kelley Professor of History at New York University and lives in New York and Madison, Wisconsin.

To learn more about The Second Coming of the KKK, click here.